Updated: 9 March 2019 |

|

Walk page: Click to view |

Appendix to the Westminster walk

MORE ABOUT WESTMINSTER

In-depth profiles of some of the most significant places mentioned in the Westminster walk, together with some pictures.

WESTMINSTER BRIDGE was erected in 1750, but only after a very lengthy battle with vested interests. (Some things never change!) It was the ferrymen who had strongly objected – for centuries they had made a good living taking people back and forth across the Thames. But another strong objector was the Archbishop of Canterbury; his interest was in a horse ferry he owned a little further up the river, and which was apparently very lucrative. And as the nearest bridge upstream at the time was eleven miles away at Kingston, it’s easy to see why the ferries were so profitable.

The original bridge had to be replaced a few years later due to subsidence and structural problems and the one you see today opened in the early 1860s. It was refurbished and repainted in 2007.

The view from the opposite side of the river, looking back across to Westminster and the rest of London, inspired the poet William Wordsworth, who had stood there very early one September morning in 1802, to write the poem entitled – “Composed Upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802”.

“Earth has not anything to show more fair,

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty;

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne’er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!”

WESTMINSTER, the early buildings and WESTMINSTER ABBEY

The land immediately surrounding the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Abbey was wet and marshy as the two tributaries of the Tyburn, a river that rises in Hampstead, flows into the Thames at this point. As a result, the early buildings, that later became the Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey, were built on an ‘island’ of slightly higher ground that had formed between the river’s two tributaries. It was known as Thorney Island because it was covered with thorn bushes.

The first building here is said to have been a Roman temple to the God Apollo that was subsequently destroyed in an earthquake. However, no actual proof has been found of its existence, though it is known that because the River Thames was slow moving at this point, the Romans had built a ford, making it an attractive spot for a settlement to be established.

Trying to establish who built what and when here is difficult, as it seems to vary according to which historian’s account you read. Almost certainly, the first Christian church on the site was built around the early 7th century by one of the Saxon kings, and I have read conflicting accounts of which one that was. Some say that it was Offa of Mercia (him of the Dyke), whilst others say that he was behind the original church on the site of St Paul’s Cathedral and that the one in Westminster was the work of King Sebert, who founded a monastery here.

Legend has it that the reason for a church being built here and called ‘St Peter’s’ was that it was where a fisherman called Edric, having seen the Apostle Peter standing on the riverbank, then rowed him across. As a thank you to Edric, St Peter is said to have rewarded him by enabling him to have huge catches of fish. There are depictions of salmon in the floor of one of the older parts of the Abbey. In addition, the Worshipful Company of Fishermen, one of the City of London’s livery companies, offers a salmon to Westminster Abbey each year in memory of this ‘event’.

Over the following centuries, various religious and royal ‘notables’ have been involved in the development of what became Westminster Abbey. St Dunstan reformed the church as a Benedictine Abbey around 960, when it was also first adopted as a royal church, and the Viking invader King Cnut, (Canute), is also said to have enlarged both the church and a nearby palace, remains of which have been found close to today’s Parliament Square.

King Edward the Confessor, the last of the Saxon Kings, had a ‘vision’ in around 1040 that called on him to rebuild and significantly extend the Saxon church to make it suitable for royal functions and burials and to include a monastery. He was the first monarch to be buried here, and from that time on, many Kings and Queens have been buried here.

After St Edward the Confessor’s coronation in 1042, the church was considerably enlarged, the real beginning of the Westminster Abbey as you see it today, building it in the increasingly popular Romanesque style that was popular in France, whilst at the same time, building himself a royal palace. He died in 1065, a year after the Abbey was completed, and was buried here.

Over time, the church had begun to be known as a ‘minster’ – the word meant a church linked to a monastery – and because there was already a minster a couple of miles to the east called St Pauls, this one became known as the ‘West Minster’. Which, of course, has stuck!

In 1066 William, Duke of Normandy, sailed from France to invade England and he adopted both Edward’s monastery and palace as his own, which he also set about enlarging. William was the first monarch to be crowned here, something that has remained the custom to this day.

For several centuries, the capital of England had been in the city of Winchester but, as a result of William’s influence, that began to change and very gradually the seat of power moved to Westminster. His son, William II, expanded Westminster Palace still further.

King John, who ruled from 1199 until 1216, continued the progression of moving the centre of power from Winchester to Westminster and by 1245, the Royal Throne was erected in Westminster Hall. Some fifty years later, the Chancery (the administrative branch of the Crown) was also established here. A key element of the Magna Carta had been having the ‘Court of Common Pleas’ based in one place, as opposed to moving around the country, and this also moved to Westminster.

Around 1245, Henry lll made many more changes to both the Palace and Abbey, retaining just the nave and rebuilding much of the church in the new Gothic style that we see today. At enormous expense, he also built a shrine to his predecessor, Edward the Confessor, who had become a Saint in 1161, which is now one of the most visited parts of the Abbey.

As already explained, the Abbey was both a Benedictine Monastery and church, but following Henry Vlll’s split with the Catholic church of Rome, because it wouldn’t allow him to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, he closed most of the monasteries in England – an act that is known as the ‘Dissolution of Monasteries’. However, he was then faced with the problem of what to do with this ‘Church of St Peter’ as it also had a monastery. He cleverly solved the problem by simply bestowing it with the title of ‘Cathedral’. That meant it then came under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of London, who caused great controversy when it was discovered he was diverting Westminster Abbey’s considerable finances to St Paul’s Cathedral, which was his own personal favourite. And that is where the expression ‘Robbing Peter to pay Paul’ is said to have originated!

It wasn’t under the Bishop of London’s control for long, as a few years later, Queen Elizabeth l declared it to be a ‘Royal Peculiar’. That meant that although it still remained a part of the Church of England, it came under the control of the reigning Monarch of the day, and not a Bishop or Archbishop which it still is today. (Other examples of Royal Peculiars include the Queen’s Chapel in St James’s Palace, the Chapel of St John in the Tower of London and the Queen’s Chapel of the Savoy, which is behind London’s Savoy Hotel).

And I find it is interesting that until the 19th century, Westminster Abbey was the third ‘seat of learning’ in England, after Oxford and Cambridge.

Today the Westminster Abbey is the largest church in Britain and has the highest nave; it is also one of the finest examples of Gothic architecture.

And finally, despite everyone knowing it as ‘Westminster Abbey’, its official name is the Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster.

THE PALACE OF WESTMINSTER

The history of the early Palace of Westminster is closely linked with that of the nearby Abbey. The palace was built by Edward the Confessor in the mid-eleventh century, at the same time as he was building the Abbey. However, we can still see today some of the building that was carried out by his son William II, which I mention shortly.

It become the principal residence of kings and queens until 1534, when for two reasons that ended. The first was because of a fire in the royal private quarters, and the second because Henry VIII was envious of Cardinal Wolsey’s nearby York Palace, which was much larger. So Henry ousted Wolseley and broke with tradition by moving himself there, renaming it Whitehall Palace.

Further additions were made to the Palace in the 13th century but sadly in 1834, some five hundred years later, most of it was destroyed in a massive fire, with just the 11th century Westminster Hall surviving. That was the earliest, and said to be the finest, part of the palace and it can still be visited today on tours of the Houses of Parliament. From the 13th century onwards, the English parliament had more or less continually met in the Palace of Westminster, (and still does, as it is the official name of the Houses of Parliament), though until it was rebuilt following the fire, they met in Westminster Abbey.

(And I must just mention that the fire was watched from the other side of the Thames by the JMW Turner, who, using his wonderful sense of colour for further dramatic effect, produced several amazing paintings – my favourite being the one called ‘The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons’.)

William lV, apparently not liking Buckingham Palace, offered parliament the opportunity to move there, but they said it was unsuitable for their requirements and politely declined. (I find it interesting that few royals have actually liked Buckingham Palace; our present Queen is said to prefer Windsor Castle. Indeed, St James’s Palace is still today the official home of the reigning monarch.).

Following the fire, a competition was held for the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster and it attracted nearly a hundred entries. It was won by architect Charles Barry, who had suggested the Gothic Revival design we see today. He enlisted Augustus Pugin, a little known 23-year-old draughtsman/architect, to help with him with the drawings, but became so impressed with his abilities that he asked him to design whole of the interior. And the magnificence of what Augustus Pugin achieved is quite breathtaking – it’s worth visiting just to see that!

During the Second World War, the House of Commons was badly damaged by a bombing raid and the House of Lords allowed them to use their facilities. After the war, another famous architect, Sir Giles Scott, was awarded the commission to rebuild it, but because of the country’s post-war economic difficulties, strict limits were imposed on how much could be spent. This resulted in a design for a simpler Chamber than before, though still in keeping with the work of Charles Barry and Augustus Pugin and with the ‘gravity that one would expect from our state parliamentary buildings’.

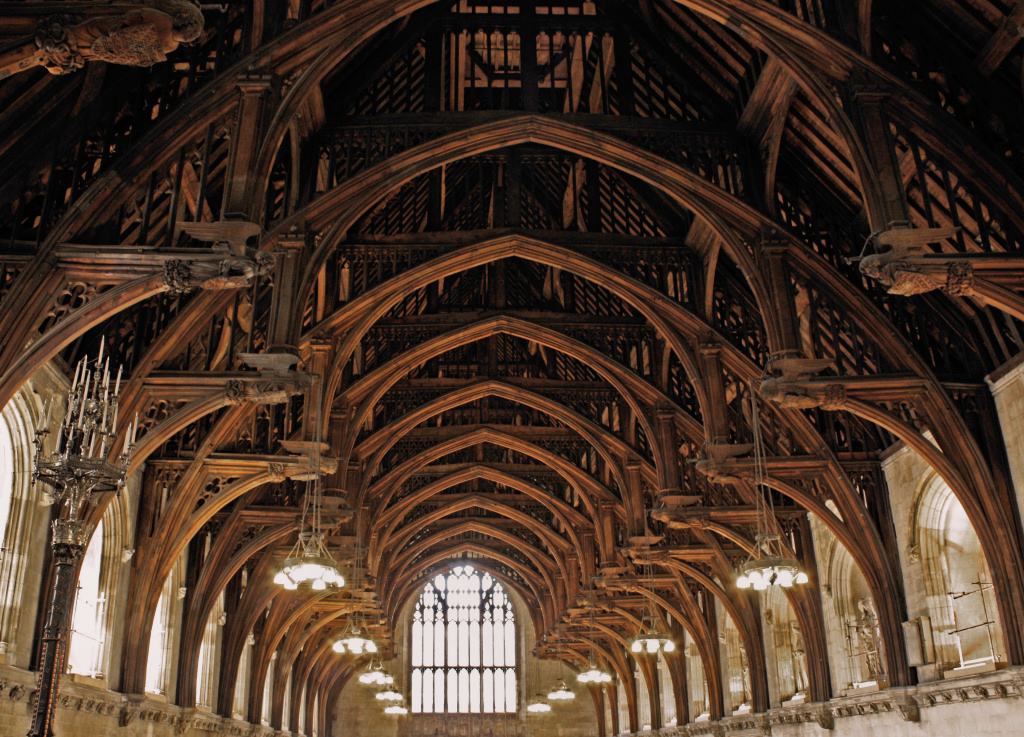

WESTMINSTER HALL is said to be one of finest examples of neo-gothic architecture and interiors in the world and not surprisingly, is both Grade I and UNESCO listed. Parts of it, including the outer walls, are a thousand years old! Its magnificent timbered ‘hammer-beam’ roof, the hall’s most outstanding feature, has been described as ‘the greatest creation of medieval timber architecture’, though it’s not quite as old as the walls that support it, having been replaced in the late 1300s. So, it’s only 700 years old!

Westminster Hall had survived the fire 1834 and, thanks to the quick thinking by firemen, the ancient hall was one of the few parts that escaped being damaged in in a bombing raid in the Second World War. Bombs had hit both the Hall and the Chamber of the House of Commons Hall and the firemen realised straight away that there was only time to save one of them; fortunately, they chose to save the ancient Westminster Hall. If you get the chance to come back and have a tour of the Houses, you can’t help but be amazed by the sight of Westminster Hall.

Following the fire, rebuilding eventually took place and following a competition when nearly one hundred architects submitted their plans, they eventually those of Charles Barry.

But back to its origins; the Hall was used for ceremonial purposes almost from its inception; this includes things too varied to mention, but to give more recent examples, both Sir Winston Churchill and the Queen Mother were ‘Laid in State’ here; several notable and world famous persons have addressed a joint assembly of MP’s and Peers here, including the Pope, Nelson Mandela, and President Obama as well as celebrations to commemorate events, including the 50th anniversary of the ending of the Second World War and several of the current Queen’s anniversaries, such as her Jubilee

THE PALACE OF WHITEHALL

It’s hardly surprising that people can get confused about the Palace of Whitehall – particularly as it no longer exists, and it was only a few hundred yards apart from the Palace of Westminster.

Although parts of it had existed before, Whitehall Palace is considered to date back to 1240 when it was the residence of the Bishop of York. However, by the 1500s it had become the home of Cardinal Wolsey who, besides his religious duties, was King Henry Vlll’s Lord Chancellor and responsible for many things including England’s foreign affairs. He amassed great wealth, some of which he used to enlarge the Palace. With over 1,500 rooms, it became one of the largest palaces in Europe, only Versailles later exceeding it.

Spread over 23 acres, from Northumberland Avenue in the north to present day St James’s Park in the south and from Horse Guards Road to the River Thames, it was bigger and better than the nearby Palace of Westminster where King Henry Vlll was then living. Needless to say, the King was rather envious. Not long afterwards, Henry and Wolsey fell out after the latter sided with the Pope and refused to sanction Henry’s request to have his marriage to Catherine of Aragon annulled to enable him to marry Ann Boleyn.

Following a fire in Henry’s private apartments in Westminster Palace, he became increasingly envious of Wolsey’s Whitehall Palace, and is said to have eventually confronted him with the words “What use is such luxury to a man of the cloth?” The Cardinal wisely decided not to argue and agreed to give it to him. Unfortunately, it didn’t do the Cardinal much good; Henry still had him arrested, and Wolsey died enroute to his trial. Henry of course, did marry Anne Boleyn, with the ceremony taking place in his new palace, as he did later to Jane Seymour. He died here in 1547.

Until 1530, the Palace of Westminster had been the principal London residence of English monarchs, but this changed when Henry moved into Whitehall Palace and it continued to be the main residence of British monarchs until it was burnt down and was destroyed in 1698. Following this, reigning monarchs returned to live at Westminster Palace, but eventually St James’s Palace and then Buckingham Palace became their favoured residence.

Today, with the exception of the Banqueting House, which I mention next, the only remnants of Whitehall Palace are the old stone steps that lead down to the river and you see these on the walk. (The palace’s enormous wine cellars are still in place but being under the nearby Ministry of Defence building are sadly ‘out of bounds’.)

THE BANQUETING HOUSE was a later addition to the palace and built in 1622 by James l. It was designed by the renowned architect Inigo Jones who, following a period of time that he spent in Italy, introduced a new Italian style of architecture to Britain. The style was known as ’Palladian’, after the Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, who in turn had been influenced by both Greek and Italian architecture. (Jones later adopted the same Palladian style for other London buildings, such as the Queens House at Greenwich that’s now part of the National Maritime Museum and much of Covent Garden.)

The Banqueting House wasn’t just for banquets though; huge court events, balls and ceremonies were conducted within its building and gardens. Whilst it’s not high on the list of most visitors to London, I have to say the enormous first floor room, known as the Banqueting Hall, where besides great feasts, many balls and other ceremonies took place, is magnificent and particularly worth seeing.

For many people, its most spectacular feature is the wonderful, colourful painted ceiling – actually nine individual paintings that were commissioned by Charles l to be inserted into Inigo Jones’ beautifully carved ceiling. They were painted by the famous Flemish Baroque artist Peter Rubens in 1636.

The building has been fully restored and has become a national monument and part of the Royal Palaces collection and is open to the public.

And ironically, it was on a scaffold outside the Banqueting House and overlooking Whitehall, where Charles l ended up having his head chopped off. He was led out to the scaffold from a first-floor window, handed his gloves to the Bishop who was there to give the Last Rites, and said, “I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible Crown”. The executioner, having just wielded his axe, held up Charles’ head and said to the crowd who had come to watch, “Behold, the head of a traitor”.

If you’d like to visit, it’s at the end of Horse Guards Avenue, on the corner of Whitehall, where we walk next. It is open to the public daily from 10am to 4.30pm.

And just for added background interest: the idea of a ‘banquet’ comes from medieval times. Rather than simply a sumptuous feast as we might regard it today, it was then a rather unusual meal of exotic deserts and snacks that was eaten on special occasions after the meat course, whilst waiting for the evening’s entertainment to begin. As time went on, people began to build special rooms or even ‘houses’ to hold them in, often a short walk away from the main dinner hall. James l’s Banqueting House in Whitehall was the biggest and grandest of these buildings. Whilst it was formerly used as an impressive reception hall for ambassadors, it was then intended for the ‘playful activities’ that took place after dinner, such as parties and court masques. These were extravagant theatrical productions, performed for and by the Stuart kings and queens and their courtiers, which portrayed them as God-like monarchs who brought peace and prosperity to a troubled land.

WESTMINSTER SCHOOL was set up in the 12th century by the Benedictine monks of the priory on the orders of the Pope. It was initially a charitable institution and called St Peter’s College (St Peter’s being the official name of Westminster Abbey). Today it’s one of the most prestigious schools in the country, as well as one of the most expensive and is renowned for having one of the highest levels of passes at GCSE.

The list of ‘school traditions’ is long – one being that the pupils are allowed special privileged access into the public galleries of the Houses of Commons and Lords – this was apparently given in order to stop them from climbing onto the roof of the building and trying to get in that way. That was a long time ago though! Another is that the teachers of the school are entitled to get married in Westminster Abbey, which is quite some perk!

METHODIST CENTRAL HALL

This rather grand Grade II listed building was built in 1912 as the ‘home’ of the Methodist Church. It is normally open to the public, free to enter, and definitely worth at least a quick visit. Take the steps up to the Upper Entrance Hall and then continue on up the Grand Staircase (there’s a good view from the window on the stairs.)

The spectacular inner dome – a single piece of cast reinforced concrete – is said to be the second largest of its type in the world. (The outside dome rises 70 feet above this.) Within this is the building’s principal feature, the Great Hall, which by making use of cleverly designed cantilevered balconies, can seat around 2,000 people. It is famous for some of the many important meetings that have been held here and Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi and Winston Churchill are among the many who have delivered speeches in the hall. It was also where, in 1946, the first meeting of the General Assembly of the United Nations was held. And bringing us back to earth, you may also recognise it if you saw the film ‘Calendar Girls’. It’s also renowned for its organ and internationally famous organists regularly give concerts and recitals. (William Lloyd Webber, father of Andrew, used to play the organ here and was also the Director of Music.)

However, its principle function is of course that of a place of worship and Sunday services attract large congregations.

Finally, I will just mention that on the lower level is the Wesley Café, which serves excellent and inexpensive meals, as well as coffees and light snacks. And there are good toilets as well. (This lower level floor was used during the Second World War as an air raid shelter, with up to 2,000 people a night sleeping here.)

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED KINGDOM

This is where the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council meets.

Since the Constitutional Reform Act of 2005 provided for the establishment of a Supreme Court that separated senior judges from Parliament, this Court has taken over the role previously held by the ‘Law Lords’. It’s now the highest court in Britain and its role is the ‘interpretation and development of the law’, hearing criminal and civil cases from England, as well as civil cases from across the UK. It also deals with matters of ‘devolution’.

The court receives cases from lower courts where there is sufficient insecurity about how the law should be interpreted and applied and what precedent the lower courts should follow in future.

The justices themselves decide which cases they will hear, depending on the extent to which they raise ‘points of law of general importance’.

Basically, if a lower court feels insecure about making a judgement, particularly when due to difficulty in interpreting a particular aspect of law, then it can refer the case to the Supreme Court. It does not hold trials where guilt and innocence are decided, so there is no dock or witness stand – instead points of law are discussed – so the court rooms are specially designed to encourage an atmosphere of learned debate. Lawyers normally wear business dress rather than formal legal wear. Interestingly, the Supreme Court is the only court in the UK where proceedings are routinely filmed and available to watch online.

How the Cases are heard – normally a panel of five justices hear each case and the Court’s President and Deputy President select them. The panel can be increased to seven or even nine justices, depending on the importance or complexity of the case. (It is always an odd number to ensure that a majority decision can be reached.) The average length of a case is two days, but it can be as long as four or more.

The building it occupies was originally the courthouse for the old county of Middlesex. With the growing population (and presumably similar increase in crime), the building became too small and was demolished in 1889. Some twenty or so years later, the rather magnificent building that you see today opened. It’s described as ‘neo-Gothic with Flemish-Burgundian references’ … (hmm, yes of course – we can all see that as soon as we look at it!). It housed both the headquarters of Middlesex County Council as well as the Quarter Sessions. (Quarter Sessions were the criminal courts that were held quarterly in various parts of the country, replaced in the 1970s by Crown Courts).

When in 1964 the county of Middlesex was absorbed by neighbouring counties and much of it became part of Greater London, it ceased to become an administrative county, so the building was no longer needed

If you have time, it’s worth taking a look inside. There is an excellent permanent exhibition on the lower ground floor that explains the background, as well as another very good café!

It’s open to the public from 9am to 4.30 Monday to Friday throughout the year (except Bank Holidays), and the court itself normally sits Mondays to Thursdays. There are guided tours available on Fridays that last for approximately one hour. Security is high, with the same screening process as at airports. Photography is allowed, but not when the court is sitting.

And an interesting additional point … It is built on land that was originally occupied by Westminster Abbey’s ‘Sanctuary Tower and Belfry’, a place where those who were wanted by the law could seek refuge from their pursuers.

ST JAMES’S PARK

Previously just an area of marshland, King James l had it drained and landscaped. Although usually crowded with tourists in the summer, it is a lovely haven of peace in the midst of the busy city. There’s a lovely lake that was formed by partially damming the River Tyburn that flows from Hampstead down to the River Thames, with plenty of flamingos, swans and other waterfowl.

As you continue up Horse Guards Road, you can’t fail to notice the delightful ‘fairy tale house’ in the park on the left. It’s called Duck Island Cottage and was built in 1841 as the home of the Bird-Keeper of St James’s Park. In addition, it had a ‘club room’ for use by members of the Ornithological Society of London, who helped look after the ducks and geese. It was designed to look like a Swiss chalet so at to make it different from the more grand and formal government buildings in the area. Later, it became a storeroom for bicycles that were confiscated from people caught riding them in the park – but now it’s just an office.

DOWNING STREET

Arguably the second most well-known address in Britain (Buckingham Palace has to be the first), it was constructed in 1682. Unfortunately, there’s not too much to see, as you can no longer walk along it. I can still remember the days when you could stroll down and chat to the policeman that was always standing outside the entrance of Number 10.

Firstly, its name. It is called Downing Street after George Downing – a greedy, conniving and treacherous ‘diplomat’ (not to put too fine a point on it!) who would change his allegiances to whichever country paid him the most money, even selling Britain’s own state secrets. However, by selling even more of another country’s secrets to the British, he obtained himself a Royal Pardon. He then invested his money in property and managed to wheedle himself into favour with the Crown, persuading them to sell him the land Downing Street is on, and there he erected around seventeen extremely badly built terraced houses. (And if you are ever asked the pub quiz question: “Did a Mr Chicken ever live at 10 Downing Street?” the answer is: “Yes”. He was one of the last occupiers before Prime Minister Robert Walpole moved there in 1735, having first made extensive renovations to the poorly built property.)

There are only three of the original houses left in the street – Numbers 10, 11 and 12. Number 10 is both the office and home of the First Lord of the Treasury (more commonly known as the Prime Minister) together with numerous offices where meetings are held, and business conducted. In total there are around 150 rooms, including several very large ‘drawing rooms’, where heads of state on official visits are entertained. The building is much larger than it appears from the outside, joined to a larger and more elegant building behind it and at the rear is a terrace and a half-acre garden.

People often ask where the Prime Minister and his or her family live – they occupy a private apartment on the third floor. However, with both Tony Blair and David Cameron having fairly large families, they used the considerably more spacious apartment in No.11 next door. A long corridor passes from No.10, through No.11 and into No.12. Mrs May has probably moved back into No.10.

No.11 is the home and working offices of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, whilst No.12 is that of the Chief Whip.

‘Q-WHITEHALL’

I mentioned this very briefly in the walk, so I’ll add a little more here. ‘Q-Whitehall’ is the name given to a network of tunnels that were built in the Second World War under Whitehall, and extended at the height of the Cold War in the 1950s. A ‘miniature city’, though that’s far too grand a name for it, was built here that would provide a safe refuge for politicians, military leaders and the royal family in the event of a nuclear attack. Tunnels connect it with both Downing Street and Buckingham Palace, but there are extensions leading to the former Trafalgar Square tube station. There’s another entrance under the Treasury building linking with what were the war time Cabinet War Rooms, and another that connects to a lift shaft in the government telephone exchange in Craig’s Court.

There are said to be a number of other similar tunnels under central London that are also still covered by the Official Secrets Act; the restriction was put in place for seventy-five years, meaning that details could be released anytime within the next ten years. Until then, this is still top secret, so I suggest that once you have read this page you chew it up and swallow it!

CABINET WAR ROOMS

After the end of the First World War, the government felt they should strengthen the Cabinet* War Rooms in case aerial bombing might be used more often in a future war.

Many top senior army officers thought this was very unlikely, no doubt the same ones who had tried to stop the Royal Air Force being formed after the First World War, on the grounds that it would never be needed!

Fortunately, the government ignored them, and once the Second World War began and they realised that aerial bombardment was indeed the future, the basements of the Treasury were turned into bomb proof bunkers, with layers of thick concrete slabs placed above them to provide additional protection. They even put netting across the top of the surrounding buildings to try and catch any falling bombs, and seals on the entrance doors in case of gas attacks. It became a completely self-contained unit – some called it a fortress. Interestingly, Churchill didn’t like them, but was forced to ‘toe the line’ and use them.

Although when you visit there seems a lot to see – around thirty different rooms, some of which are very large – this is only a small part of an incredible three acres of underground facilities. There were two levels that included a hospital with an operating theatre, first aid posts, a firing range, canteens, emergency power station, and of course dormitories where staff could sleep. The BBC put in a studio to enable the Prime Minister to broadcast to the nation and there was even a ‘dummy private toilet’, said to be for Churchill’s use only, that actually contained a phone permanently connected to the President of the USA.

Much of what you see today has hardly changed since the war ended and these facilities were abandoned – for example, many original maps, posters and signs are still on the walls.

You discover all this and of course much more by visiting the War Rooms. I don’t suggest you try and combine it with this walking tour – firstly, to avoid long queues you normally need to book in advance, and in addition you need to allow a couple of hours to take it all in. There really is a lot to see and read.

* The Cabinet is the supreme directing body of central government, bringing together the Prime Minister and the principal government ministers. In wartime, the Prime Minister assembles a select group of ministers to form a War Cabinet, with executive powers to facilitate the decision-making process. Churchill succeeded Neville Chamberlain as Prime Minister in May 1940 and his War Cabinet of eight members was a coalition of both Conservative and Labour Ministers. Churchill also took on the role of Minister of Defence.

WHITEHALL COURT

Running the full length of the street of the same name, this enormous and rather beautiful neo-Baroque building opened in the 1890s. It’s modelled on a French chateau and is two separate buildings that are joined.

However, as the Royal Horseguards Hotel have now taken over a considerable part of Whitehall Court, the division between some floors between the two buildings have been removed.

Built to house luxurious residential apartments, many well-known figures such as Lord Kitchener, HG Wells and George Bernard Shaw have lived here.

In the text of the walk I mention that few, if indeed any, of the early occupants of these apartments probably ever realised that the building’s doormen and commissionaires were actually special branch police officers – the reason being that at one time the top floor of part of the building was the offices of the newly formed secret service, known now as MI6, and they were there to keep an eye on who came in and out of the building, in particular, looking out for foreign spies or agents. Indeed, MI6’s presence was kept so secret that not only were the other residents unaware of it, but even those who probably should have known weren’t aware either! So much so that when he first moved in, Commander Mansfield Smith-Cumming who had just been appointed head of MI6, on a number of occasions wrote in his diary, “Another day without visitors”, apparently little realising that the authorities had kept it so secret that no one knew he was there or how to find him!

The eastern end of the building was once owned by the Liberal Party, the political party started by William Gladstone, and known as the National Liberal Club, but it’s now a Gentleman’s Club, said to be the one of the largest in the world. Besides its elaborate Thames side terraces, dining rooms and spacious function rooms, there were at one time over 140 bedrooms for its members. During the First World War it was taken over as billets for Canadian troops, later reverting back to be the Liberal Club, which has been the site of a number of major political events.

During the Second World War, it was again taken over by the government and used by both MI5 and MI6, despite receiving a direct hit from a war time bomb. In 1973, it was damaged once again, this time by an IRA bomb.

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, the club’s membership was dropping and they couldn’t afford to undertake the amount of renovations that were needed. As a result, they decided to sell a considerable part of the building, including 140 bedrooms and two ballrooms, to the adjacent Royal Horseguards Hotel, which had opened there in 1971 after MI5 and MI6 had moved out.

The hotel is now spread over nine floors and has 282 rooms. Following a fairly recent major upgrade, it now has a five-star status and, owing to its proximity to Parliament, has become very popular with politicians and civil servants. (There is even a ‘division bell’ in the bar and public rooms to alert MPs when a vote is being taken in the House of Commons, to which they then hurry across.) As mentioned before, the hotel also owns the conference and events centre within the same building.

Despite all of that, the National Liberal Club is still there, and whilst somewhat slimmed down, retains some of its elaborate Thames-side terraces, dining rooms and function rooms.

As a matter of interest, many people may have seen various parts of the inside of the Club, as over the years it has been used in countless films, a list far too long to mention.

(And a final note, I mentioned previously that part a major part of the building’s original purpose was for residential apartments and a number are still there; recently I noticed a flat in the building being advertised for over £4 million.)