Updated: 11 July 2024 |

|

Walk page: Click to view |

Appendix to the Clerkenwell walk

MORE ABOUT THE AREA’S HIGHLIGHTS

An introduction to Clerkenwell and in-depth profiles of some of the most significant places mentioned in the walk, together with some pictures.

AN INTRODUCTION TO CLERKENWELL

The area known as Clerkenwell developed from a hamlet serving the monasteries that had been established here from the 11th century. The name ‘Clerkenwell’ came from a fresh water spring, near which the parish clerks (a term used for someone who was a member of the clergy or perhaps just highly educated) would organise and put on religious plays. These would be watched by the mainly illiterate local people, with the hope it might give them an insight into the bible, which of course, they couldn’t read.

Its proximity to the City of London and its good water supplies meant that it grew quite rapidly, particularly in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and this resulted in it becoming extremely overcrowded and subsequently infamous for its slums and levels of crime.

The area centred on the Priory of Clerkenwell, the headquarters of the Knights Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem, whilst also close by were the Priory of Charterhouse and St Mary’s Nunnery. All three were closed down during Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries.

Being outside of the City of London, Clerkenwell was free from the standards of behaviour and various restrictions that those living in the City were forced to abide by. As a result its reputation for crime, violence and prostitution steadily grew; prostitutes, who were banned from plying their trade within the City, established themselves as close as they could, whilst staying outside its walls.

A description of Clerkenwell in the 16th century read, “there were a great number of dissolute, loose, and insolent people” … harboured in “noisome and disorderly houses, poor cottages, and habitations of beggars and people without trade … taverns, dicing houses, bowling alleys and brothel houses.”

The infamous reputation of streets such as Turnmill Street was referred to by Shakespeare’s Falstaff, whilst another account said this was “the most disreputable street in London, a haunt of thieves and loose women”.

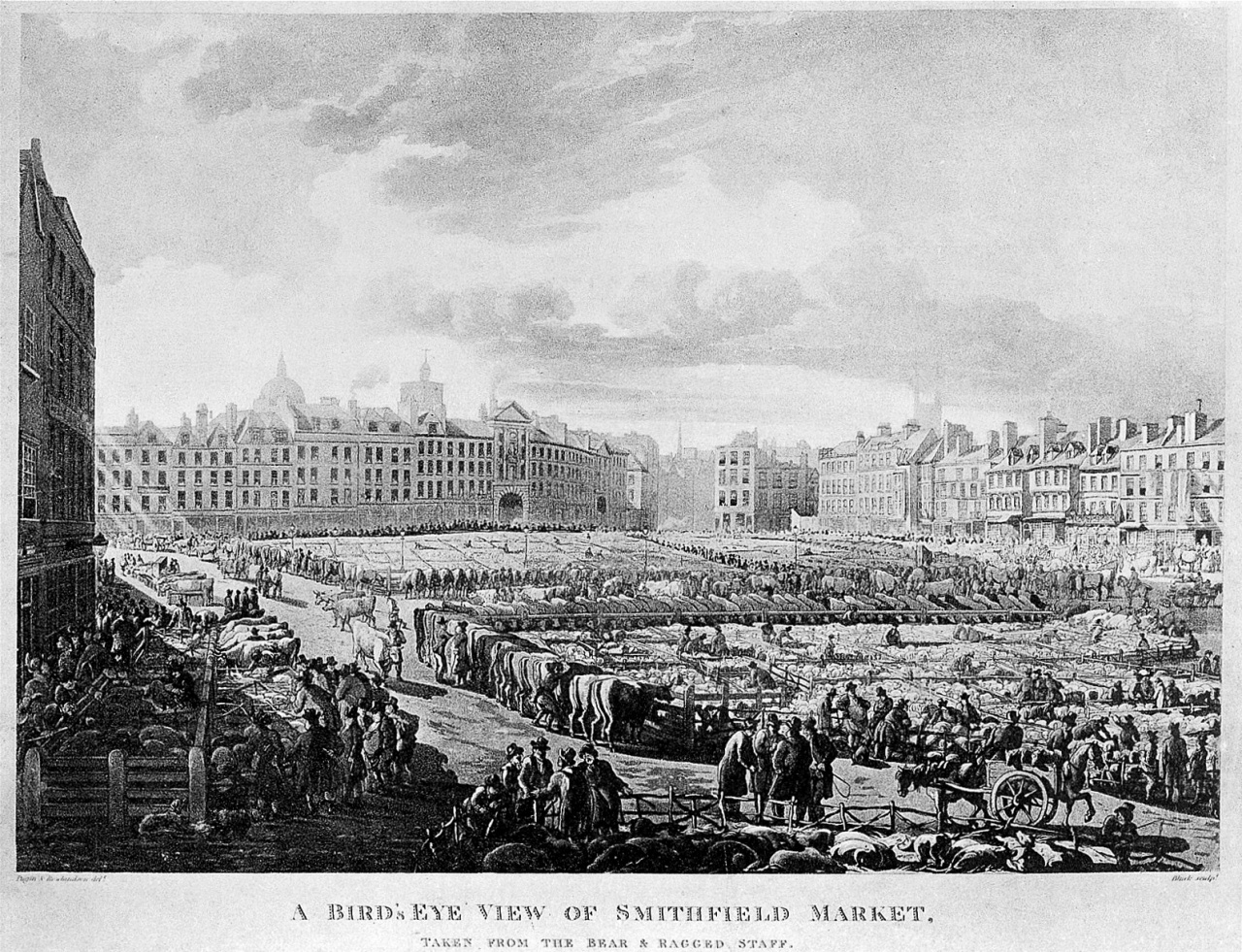

The cattle market that had been established in Smithfield continued to grow, bringing with it yet more ‘disreputable people’, resulting in it being closed and the building of the famous Smithfield meat market, which could be more easily controlled.

The annual Bartholomew Fair, which used to attract vast crowds, was held each year around the saint’s feast day on August 24th, and eventually became so troublesome that in 1855 the authorities banned it from ever taking place again.

However, over time some areas of Clerkenwell did begin to improve and small industries started to develop. The good water supplies meant it became a popular place for brewing and gin distilling – Nicholson’s gin distillery was based here until 1961, though its building has now become trendy apartments.

During the 17th century many Huguenots, escaping from religious persecution in northern Europe, settled in Clerkenwell and brought with them their highly specialised skills, such as clock and watchmaking, which by the early 18th century the area had become well known for.

Another area of Clerkenwell became known as Little Italy as a result of the number of immigrants from the northern part of that country that began to settle there. A report by the Italian consul in 1895 said that most of them were working as ‘organ men, ice vendors, ambulant merchants and plaster bust sellers. However, Little Italy doesn’t exist anymore, as the Italians moved on to live elsewhere in London. By the mid-19th century the area’s reputation once again began to decline, and it had some of London’s worst slums.

Somewhat ironically, bearing in mind its history of crime and violence, Clerkenwell eventually became a sort of ‘centre of justice’, with the huge Middlesex courthouse being built at the bottom of Clerkenwell Green and the opening of several prisons, including the Cold Bath Prison, at the time the biggest in Britain.

It also became known for its radical and revolutionary politics. John Wilkes, an 18th century ‘defender of free speech’, lived near Clerkenwell Green, as many years later did Lenin. And it’s still home to the Marx Memorial Library, which we see on the walk. Britain’s first May Day march, which is still very popular with communists and socialists, set off from Clerkenwell Green – as it continues to do every year.

SMITHFIELD AND ITS MARKET

Situated just outside the walls of the City of London, Smithfield is one of Britain’s oldest surviving urban areas. A priory and a hospice (the forerunner of the first hospital to open in Britain) which were dedicated to St Bartholomew were established here in 1102, receiving a significant income from the adjacent annual ‘cloth fair’, which became one of the biggest cloth markets in Europe.

The name ‘Smithfield’ comes from its early description as a ‘Smooth Field’, a broad grassy area that led down to the River Fleet. It was ideal for the watering and the grazing of cattle, hence the growth of the cattle market that had been held there since medieval times. Indeed, centuries ago, Welsh drovers would herd their flocks from the hills of Wales to the ‘sale yards’ that were in front of the St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

The streets around Smithfield were always full of live animals on their way to the market or slaughterhouses and Dicken’s description of it reads, “It was market morning. The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire; a thick steam perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle and mingling with the fog, which seemed to rest upon the chimney tops … unwashed, unshaven, squalid and dirty figures constantly running to and fro, and bursting in and out of the throng, rendering it a stunning and bewildering scene, which quite confounded the senses”.

Besides the Cloth Fair that was held on St Bartholomew’s Day on August 24th each year was the annual St Bartholomew’s Fair, that even by the reign of Elizabeth I it had become notorious for the crime and violence that it caused. Prostitutes had been banned from plying their trade within the City walls and had established themselves in Smithfield, so it was hardly surprising that its reputation worsened over the centuries. Rife with muggers and pickpockets it had a reputation as being one of the roughest places in London, with a particular dislike of outsiders. Indeed, in the 19th century the area was said to have the highest murder rate in London and was described as ‘a den of thieves and murderers’. Indeed, Charles Dickens based Fagin and Bill Sykes, the villains of his 1838 novel ‘Oliver Twist’ in Smithfield, on two such characters that he was said to have met here.

Smithfield was also known for its ‘wife sales’. Yes, you read that correctly! In the early 19th century getting a divorce was extremely difficult, so men would bring their wives along to sell, along with their other goods, and at the end of this section I reproduce a ballad that was popular at the time.

All of this resulted in a concerted effort by the authorities to ‘clean the area up’ and in 1855, after 600 years, the fair was finally shut down.

In addition to this, in 1852 the Smithfield Market Removal Act was passed, forcing the live market to relocate to Copenhagen Fields in Islington, and in its place Sir Horace Jones, the City of London’s Surveyor, designed the buildings for a new meat market which opened in 1868, much of which we still see today.

It had a quite revolutionary design, with iron pillars that supported iron lattice girders that let in both light and air and a louvred roof that helped keep the sun out. All of that, as well as its location being slightly higher than its surroundings, meant there was more of a breeze which helped to keep the temperature cooler than outside. This was obviously good for keeping meat fresh in the days before refrigerators.

The market was a great success, so much so that several years after the main market buildings opened, it was further extended by the opening of the poultry market to the west of the meat market.

All of this, together with the newly constructed Metropolitan line that actually ran under the market, contributed to Smithfield’s continuing growth and success. The new railway line meant a station could be built under the market, allowing special trains to bring the meat directly here from all parts of the country. Alongside it, enormous underground storage areas, accessed by the wide circular ‘ramp’ you see today enable the meat could be brought up into the market. Those storage areas are now used as a car park.

Obviously there were many changes in the Second World War, when the market was closed by the government who were concerned about large gatherings of people in buildings that were easily recognisable from the air. The meat stores were then spread around London, with just small amounts stored at Smithfield and some of the space left was used as an army butchers’ school.

The market was badly bombed during the war – indeed it was hit as late as early 1945 by the last but one V2 rocket to land in England, when the fish, fruit and vegetable sections of the market were badly damaged, and 160 people were killed. War-time rationing of course had its effect, which didn’t end until 1954 when the market gradually returned to normal activities.

Following the war, the market was rebuilt and today still supplies much of the meat for London’s restaurants, wholesalers, etc. However, it is now in decline and the Corporation of London, which owns the site, has announced plans for it to close and move to Barking Creek, in east London. This will be wonderful news for the many developers who’ve been desperate to get their hands on such a prime ten-acre site. Its western end is already in the process of being redeveloped as the new home for the Museum of London.

Finally, during research into the market, I read an article about some of the old trades that were connected to it and found the following paragraph, which I found rather interesting, so I thought I’d share it here:

“For centuries so much of the trade of the area around Smithfield had been based around the cattle market and apparently even as late as 1980 a few of those old trades were still in existence – bacon smokers, sausage skin makers, pie men, cutlers – even button makers (buttons were made from the hoofs and horns of the cattle).”

I mentioned Smithfield’s wife sales earlier – and here is a ballad that was written in 1811:

John Hobbs and His Wife

A jolly shoe-maker, John Hobbs, John Hobbs,

A jolly shoe-maker, John Hobbs;

He married Jane Carter,

No damsel looked smarter,

But he caught a Tartar,

John Hobbs, John Hobbs,

Yes, he caught a tartar, John Hobbs.

He tied a rope to her, John Hobbs, John Hobbs,

He tied a rope to her, John Hobbs,

To ’scape from hot water

To Smithfield he brought her,

But nobody bought her,

Jane Hobbs, Jane Hobbs,

They all were afraid of Jane Hobbs.

Oh, who’ll buy a wife? Says Hobbs, John Hobbs,

A sweet pretty wife says Hobbs;

But somehow they tell us,

The wife-dealing fellows,

Were all of them sellers,

John Hobbs, John Hobbs,

And none of ’em wanted Jane Hobbs.

The rope it was ready, John Hobbs, John Hobbs,

Come, give me the rope, says Hobbs,

I won’t stand to wrangle,

Myself I will strangle,

And hang dingle dangle,

John Hobbs, John Hobbs,

He hung dingle dangle, John Hobbs.

But down his wife cut him, John Hobbs, John Hobbs,

But down his wife cut him, John Hobbs, John Hobbs,

With a few hubble bubbles,

They settled their troubles,

Like most married couples,

John Hobbs, John Hobbs,

Oh happy shoe-maker John Hobbs.

ST BARTHOLOMEW’S HOSPITAL

– and the role it played in improving the standard of nursing care in Britain

St Bartholomew’s, regarded by many as England’s ‘premier hospital’, played a major part in improving the standards of nursing care and the working conditions for nurses. Two of the early matrons were largely responsible for this. One was Ethel Gordon Manson who was appointed matron in 1891. Sadly, she had to leave in 1887 to get married (married women weren’t allowed to continue working then) and later as Mrs Bedford Fenwick, she began a 30-year campaign for state registration of trained nurses. This wasn’t actually achieved until 1919 when an Act of Parliament was passed, and the General Nursing Council was established – Mrs Fenwick then becoming ‘State Registered Nurse No. 1’.

Her position as Matron was taken over in 1887 by Isla Stewart, who was Matron from 1887 until 1910, and who continued the campaign for the state registration of nurses. She was also an ardent campaigner for the formal training and education of nurses and became the first Superintendent of St Bartholomew’s Training School as well as founding the League of St Bartholomew’s Nurses.

A plaque on a wall where the house of Dame Joanna Astley, nurse of Henry VI, once stood explains that this particular building is “devoted to the elucidation of problems in the nature and treatment of the diseases of those who have sought relief from suffering in this hospital.”

She saw a nurse as a working woman, “wishing for independence … and to have a profession … owing no man anything.” One of her quotes was “There was something about St Bartholomew’s Hospital – it may be its age, its history or its associations – which creates towards it a unique feeling among its members.”

As a result of their efforts, from 1925 onwards pupils would spend seven weeks at a preliminary training school before starting work at the hospital.

ST BARTHOLOMEW’S HOSPITAL MUSEUM

I mentioned the museum in the text of the walk and said it is fascinating and well worth a visit but I felt that it is worth a little more of a mention.

There are a number of detailed information boards and exhibits that cover the history of the hospital as well as explaining how nursing and medical knowledge has progressed over the centuries.

For example, you learn that at one time there were usually three hospital surgeons attending to the patients. They were initially apprentices and regarded as being craftsmen. The surgeons were subordinate to the hospital’s physician and had inferior status, something that didn’t change until the 18th century. However, some of the early surgeons at Bart’s were skilled practitioners and highly regarded in their day.

From the 16th century until later in the 19th, surgery was a rather crude and barbaric affair and operations were actually quite rare. For example, in the 1770s only around one a week were performed at the hospital and the most common were amputations and lithotomy (the removal of bladder stones, a common complaint in those days). Another ‘remedy’ for certain ailments was the removal of pieces of the skull.

Surgeons more commonly dealt with accidents and injuries caused by knife and gunshot wounds, burns and fractures. They also pulled teeth and treated skin disorders, venereal infections, tumours and ulcers. Enemas and blood-letting were also common in those days.

‘MONTY PYTHON AND THE GRAND STAIRCASE!’

Whilst he was in St Bartholomew’s Hospital recovering from open heart surgery, Sir Michael Palin, (star of Monty Python and author and broadcaster of fascinating travel documentaries), was taken in a wheelchair through the hospital to see the famous artistic masterpiece created by William Hogarth in 1736.

It is one of the ‘hidden secrets’ of Barts, which I was fortunate to see (as a result of an unlocked door and the fact that the person supervising the museum that day was otherwise busy when I first visited, which was a few years ago!)

To say that Michael was impressed is certainly an understatement, so much so that he has made a substantial seven-figure donation.

The staircase, which is accessed through a door in the museum, has two 30-foot canvases on its walls, both painted by William Hogarth in the 1730s. They depict scenes from the Bible – the Pool of Bethesda and the Good Samaritan. The former shows the scene from the Gospel of John when Jesus instructs a paralysed man to walk, whilst the other shows sick and injured people (thought to have been modelled on real life patients of Barts at the time), who are waiting to bathe in the healing waters of the pool.

They are the largest Hogarth ever produced and portray characters that display almost every known ailment in the late 18t century.

Will Palin, Michael’s son, who as I explain below is responsible for the renovations, says it is interesting that Hogarth was generally known more for his scandalising caricatures of political and social life. He wanted to demonstrate that he wasn’t just a popular satirist, so the opportunity to do something on this scale – a historical narrative within the walls of one of the most important institutions in the country was said to be irresistible.

Hogarth, who at the time lived locally, had heard that the hospital’s governors were thinking of hiring an Italian painter to undertake the work and, having recently completed A Rake’s Progress, he was keen to take on the job himself, and he never asked for payment.

Will Palin, who is a building heritage and conservation expert, was appointed Chief Executive of Barts Heritage, a charity founded to rescue and repair the oldest buildings within the hospital. And with the help of sizeable donations from his father and others, he has managed to raise over £10 million towards the restoration. He said it wasn’t too difficult as his father’s life was saved by Barts!

Will has already had considerable experience of such renovations as he led the team to restore the Painted Hall at the Old Royal Naval College, in Greenwich.

For the two-year project, which began in the autumn of 2023, Will has recruited experts who have already carried out restoration work on St Paul’s Cathedral and the Duomo in Florence.

CLERKENWELL PRIORY AND ST JOHN’S CHURCH

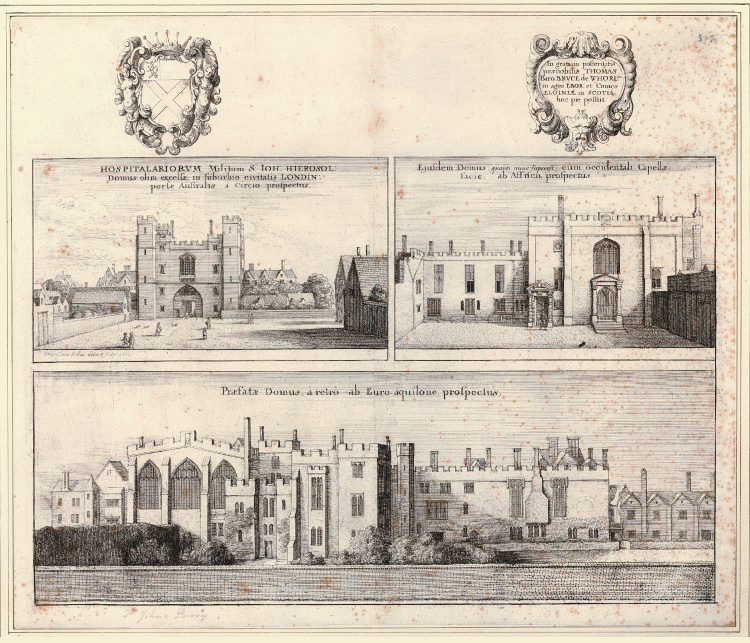

Clerkenwell Priory was founded in 1140 as an ‘Augustinian Monastic Order of the Knights Hospitallers of St John of Jerusalem’ and was the residence of the Hospitallers’ grand prior of England and therefore their headquarters. They were powerful and wealthy, owning land in areas of London such as Marylebone and St John’s Wood.

The Knights of St John were a religious order, founded in Jerusalem around 1099 to care for sick and poor pilgrims. Later they developed a military role, moving from Jerusalem to Acre, Cyprus, Rhodes and then Malta. I rather like an account, written in 1237, of their departure to the Holy Land, which I quote here;

“The Hospitallers sent their prior … a most clever knight, with a body of other knights and stipendiary attendants and a large sum of money to the assistance of the Holy Land. They having made all arrangements, set out from their house at Clerkenwell and proceeded in good order, with about thirty shields uncovered, with spears raised and preceded by their banner, through the midst of the City, towards the bridge, that they might obtain the blessings of the spectators, and bowing their heads with their cowls lowered, commended themselves to the prayers of all.”

Later the prior had many roles and was the first secular baron in Parliament, as well as having other civic and judicial duties. He also sat on the King’s Privy Council, a committee that offered the king confidential advice on affairs of state. Priors also held their own courts and were responsible for local justice on all the lands the order owned.

The priory must have been quite substantial building and was said to resemble a palace with a ‘very fair church and a tower steeple raised to a great height with such fine workmanship that it was a singular beauty and ornament to the City”. Few knights actually lived there, but many would pass through on their way to the Holy Land, Rhodes or Malta. The actual residents included the church chaplains and officials such as the prior himself, as well as servants and stable boys. Women did not live there, with the exception of some pensioners and the laundress.

Many royal guests stayed at the priory, including King John, Edward I, Eleanor of Castile, Henry IV and Henry V. As a result of the amount of entertaining that was done, both by the Grand Prior himself as well as various members of his court, it was constantly running out of money.

The order was dissolved during Henry VIII’s reformation and dissolution of monasteries. He subsequently confiscated their buildings and lands and, sometime later in the 16th century, part of the priory was blown up with gunpowder and the stone used for buildings elsewhere in London. Indeed, with the exception of St John’s Gate, which we mention elsewhere, there is little left of the original priory.

And I must mention the description of a feast that was held here in 1541, following Henry VIII’s ‘takeover’ of the priory. It was to honour ten newly created Serjeants-at-Arms and the food consumed by the guests included, “thirty-four great beehives, thirty-seven dozen pigeons and fourteen dozen swans”. Some feast!

The site later became the townhouse of the earls of both Ailesbury and Elgin and the church became their private chapel, with a library on one side, whilst the crypt was used as their private wine cellar.

ST JOHN’S GATE

St John’s Gate had been built as the South Gate entrance of Clerkenwell Priory but after Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, when the priory was closed, this part of the building was preserved and since then has had a variety of uses, some most fascinating.

During Elizabeth I’s reign in the 16th century the Master of the Revels, the official who had the responsibility of deciding which plays would be granted licences allowing them to be performed, had his offices here. He would often ask for a play to be performed here in front of him, so he could decide whether or not to grant a licence for it to be performed in public. England’s most famous playwright William Shakespeare came here on a number of occasions to seek licences for the performances of around thirty of his plays.

Many years later, in 1703, Richard Hogarth, the father of the famous painter William Hogarth opened a coffee house here ‘to enable gentlemen to enjoy a coffee whilst conversing in Latin’ and his son William lived here until the age of five.

An early printing press was also set up and it was here where Benjamin Franklin worked in 1725, before going to America. Indeed, it was on this press that Benjamin Franklin’s ‘Experiment and Observations on Electricity’ was printed.

In 1731 it became the offices and printers of the Gentleman’s Magazine, the famous periodical that ran for nearly 200 years. The magazine was the first employer of Samuel Johnson (who later wrote the first authoritative English Dictionary but hadn’t yet been awarded the title of doctor). He worked here as an editor and translator for the magazine. Later it was where several of Johnson’s books were printed.

In the late 18th century the gate was considered to be unsafe and various improvements were made, including the removal of the battlements that had been above it.

Over time it had also been a parish watch-house, the offices of a Masonic order and a tavern, known firstly as ‘The Old Gate’, then the ‘St John’s Gate Tavern’ and finally the ‘Jerusalem Tavern’, where Charles Dickens was a regular customer.

It was also where the famous 18th century actor David Garrick, who later had both a London theatre and street named after him – the Garrick Theatre and Covent Garden’s Garrick Street – made his first public performance.

Finally, in 1874 it was purchased by the British Order of St John, and is now used as an excellent museum that explains the order’s history – and is well worth a short visit.

THE ORDER OF ST JOHN

The order developed from the work of Benedictine monks in the Holy Land who, while tending to pilgrims in their hospice, decided that they wished to become another order. Promising Pope Pascal II that they would honour poverty, chastity and obedience, in 1115 the Order of St John of Jerusalem was raised.

They became the Knights Hospitallers and another promise was to defend the faith. They used the Knights Templar to guard them whilst they tended the wounded on the battlefields of the Crusades.

Over time the order carried on its work in areas of conflict and during the Crimean War its members went to Queen Victoria to ask for royal approval to officially re-establish the order in England – it had been dissolved by Henry VIII. Because the Pope wouldn’t approve of a multi-denominational order Victoria agreed and made it the Most Venerable Order of St John.

There was a great need to have proper medical cover in factories after the industrial revolution and the St John Ambulance Association was set up in 1877 by the Order of St John to train factory workers in first aid. It began by offering 30 or so classes around the country.

Eventually members wanted to form a uniformed volunteer squad that could attend people who became ill or were injured at public events. The first public event attended by St John volunteers was Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Parade in London.

This developed into a public ambulance service around the country and soon there were separate divisions for men and women, divided into ambulance and nursing sections. Later, children joined as cadets and later ‘badgers’. The NHS took over the ambulance service in 1948, leaving St John Ambulance still responsible for some of the work until the 1960s.

Nowadays the organisation still has uniformed members who are trained up to a high standard and includes health care professionals who give up their time on a voluntary basis. Additionally, many types of training classes are available for companies or the public. While its military aspects have been significantly reduced and the organisation modernised, with the uniform brought up to date in green and black, the principle that nobody should die for want of trained help is rigorously maintained. St John Ambulance now operates throughout most Commonwealth countries.

THE CARTHUSIAN PRIORY OF CHARTERHOUSE

The name ‘Charterhouse’ comes from the French word Chartreuse and this was one of thirteen monasteries to be established in England by Carthusians monks, a monastic order started by St Bruno of Cologne in 1084. He built a hermitage in the Chartreuse region of the Alps, north of Grenoble in France. (And if anybody wonders whether there is a connection with the ‘Chartreuse’ alcoholic drink, then yes … it was originally made by there by the monks over 300 years ago. And they still make it).

Charterhouse opened in 1371 and soon became the wealthiest of them, mainly as a result of being supported by merchants in the City of London, who no doubt hoped this gesture would help get them into God’s ‘good books’.

The life of a Carthusian monk was then – as it still is to this day – one of humility and contemplation, which is basically solitude and silence and indeed they were known as ‘hermit monks’, who were supported by ‘lay brothers’. The former lived very isolated lives in small, individual rooms, called cells, which were built along or around a cloister. (There were twenty-five of them in the Charterhouse priory). They had two meals a day (lunch and supper) which were passed to them through a small opening into their cell, which meant they did not have to see or speak to whoever brought it to them. Interestingly, in an account I have read of a visit to the monastery some five hundred years ago, it said that “thanks to their diet of mainly fish, the monks stunk like otters.”

They spent their days meditating and praying, normally only leaving the cell for prayer services in the chapel. On Sundays they often joined together with others for a ‘silent’ community meal, and once a year they met a close family member.

Charterhouse Priory

Following the Reformation, the Catholic religion was banned by Henry VIII as a result of the Pope’s refusal to allow his marriage to Catharine of Aragon to be annulled, as she hadn’t been able to provide him with a male heir. Henry then established the Church of England in its place and closed down the many Catholic monasteries, of which Charterhouse was one. He had the Prior and monks put to death for refusing to acknowledge him as head of this new church.

Following its closure, the buildings were for a time used by Henry VIII to store the equipment he used for his hunting expeditions, whilst some of the monk’s cells were used by a family of makers of musical instruments. Charterhouse was later purchased by Edward North, who Henry had put in charge of disposing of the Catholic Church’s properties in England, so no doubt for a very advantageous price.

Edward North demolished the monastery’s church and, in its place, built what was said to have been a ‘rather magnificent mansion’. This included the Great Hall and the adjoining Great Chamber, (later known as the Throne Room for reasons I explain below).

Following his death the property was purchased by Thomas Howard, who renamed it Howard House. However, as so often happened in those days, Howard later found himself incriminated in a ‘political plot’ and was put under ‘house arrest’ in his Charterhouse mansion by King Henry, for allegedly taking part in a plot to have his successor, Elizabeth l, killed and replaced on the throne by her Catholic supporting sister Mary. He used his enforced time at Charterhouse to create the magnificent gardens that we can see today. His fate was sealed when a ‘coded letter’ was found under a doormat in his mansion that had apparently been sent by Mary Queen of Scots. Not surprisingly, he himself was sentenced to death, following which ownership of the house passed to his son Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk.

Then in 1611, the property was purchased by Thomas Sutton who had made a vast amount of money as a result of the discovery of coal beneath two estates he had leased near Newcastle-on-Tyne. In his will he left money for a hospital to be built on the Charterhouse site, together with a school to educate forty boys and also a chapel. He also provided funds for an alms-house to provide a home for eighty male pensioners – ‘gentlemen by descent and in poverty, soldiers that have borne arms by sea or land, merchants decayed by piracy or shipwreck, or servants in households to the Kings or Queens Majesty …’. (Although members of his family contested his generous charitable will, they failed to have it overturned and Thomas’s good works were put in place.)

The almshouses are still there and home to ‘forty pensioners’. Although they are called ‘Brothers’, they don’t have to be practicing Anglicans, though they are expected to respect the church’s traditions. Until 2018 only single or widowed men were admitted, but since then single or widowed women can also apply. Each of the Brothers has their own individual accommodation but take their meals in the Great Hall. (The reason for being called ‘Brothers’ (or in the case of women, Sisters) is simply to respect its monastic past.) It is still run as a charity, with a board of sixteen governors, one of whom is always a member of the royal family.

And in case you might be thinking how nice to live in such a lovely community when you reach retirement, I’m told there is a very long waiting list for places.

The school became the famous Charterhouse public school. It has several interesting ‘claims to fame’, one of which is surprisingly to do with football. Back in the 19th century football was a very popular game at the school. Unlike some other public schools, being in a monastery meant that the Charterhouse boys had very little space to play football, (in practice just the cloisters) and as a result had to play to a rather strict set of rules that had been devised to cope with this.

One of these was an ‘off-side’ rule that was different from that used elsewhere, as was another that involved when the ball could be thrown. When the Football Association was being formed in the 1860’s and the rules being established, both of these rules that were used at Charterhouse were adopted for what became our national game. (Indeed, for a number of years, players from the ‘Old Carthusians’, a team made up of ‘old boys’ of the school, had great success in the FA Cup, even winning it on more than one occasion. And a number of ex-Charterhouse boys were then playing in many of the FA league teams.)

In 1872, Charterhouse School moved out of London to Godalming in Surrey, where it still is today, and is one of the ‘Great Nine English Public Schools’. Past pupils include Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt; singer Peter Gabriel; TV broadcaster Johnathon Dimbleby; John Wesley, the founder of Methodism; the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams and Baden-Powell, founder of the Scouting Movement.

The priory buildings

Two of the most important parts of Charterhouse are the magnificent Great Hall, which although damaged during the Second World War, has been fully restored and the Great Chamber.

The Great Chamber was built by Edward North in the 1540s and known then as the ‘Throne Room’. This name came about as a as a result of Elizabeth l holding her first Privy Council meeting in it before being crowned Queen. James l also held his first ‘court’ here, when he arrived in London from Scotland to take up the crown.

(And whilst it may have seemed like a great honour to have a king or queen staying with you, many would dread it. For a start, it wouldn’t just be the royals themselves and a few of their closest ‘hangers on’ – it could be dozens or even scores of members of the Royal Court and various associates. All would want accommodating, and most in great style. Enormous banquets had to be laid on with vast amounts of food and wine. And of course, none of it was ever paid for. It is said that some members of the aristocracy were virtually bankrupted as a result of a royal deciding to come to stay.

Finally, a little about the English Reformation

The reason for adding a few paragraphs on this is because I have referred to it several times during the appendix as it had such a huge influence on several of the buildings we visit during the walk.

The Reformation was a time of enormous change in England, particularly to the established Catholic Church, which in those days was a fundamental part of the way of life for many people.

It was called the ‘reformation’, because things really were reformed and changed during the reign of Henry VIII. He decided that as his wife had not yet given him a son and was convinced that she was now too old to have children, he wanted to divorce her. He had already chosen Anne Boleyn as his new wife.

Unfortunately for him, England was a Catholic country, (as was most of Europe), and divorce was forbidden – marriage really was ‘for life’. Although he was the King of England and extremely powerful, he was a Catholic himself so had to ask the Pope, the head of the Catholic Church, for permission to divorce. He could no doubt have just gone ahead but was concerned that if he did so then he would be ‘excommunicated’ (i.e. thrown out of the church). Not wanting to take a chance and upset God by going against the religion, he had a problem.

Despite his appeals directly to the Pope, he was refused permission, so in desperation, he went to the Archbishop of Canterbury, the head of the Catholic Church in England. The Archbishop knew what the Pope had said, but equally he knew it wasn’t wise to argue with the powerful King of England – so he took it upon himself to give Henry the divorce, enabling him to marry Anne Boleyn.

It’s all a very long and complicated story, but the result was that knowing the Pope’s reaction to this, Henry decided to ‘break away’ from the Catholic Church and had an Act of Parliament passed in 1534 that made him the head of the newly formed Church of England. (And of course, over five hundred years later, it is still the monarch of the United Kingdom who is head of the Church of England).

Henry probably wasn’t taking too much of a risk in doing this; he knew that many people – and not just in England but across Europe – were getting rather fed up with what was perceived by many to be the ‘money making’ methods and general corruption of the Catholic Church, which was based in the Vatican, in Rome. The church was growing ever wealthier by all manner of means, but what affected the everyday life of people was the way the church was charging them – and by no means small amounts – for everything to do with the church. To be baptised, (which the church said you had to be, or you’d never get to heaven), to get married, to be buried …

If people protested and didn’t pay, then they would be told that they would go to hell. That really worried everyday people, particularly as most were poorly educated and believed what they were told. So, even if you were very poor, you were faced with either finding the money, or spending eternity in hell!

So, in view of this growing dissatisfaction with the Catholic Church, his decision to abandon that religion and set up a new ‘Church of England’, of which he, rather than the Pope, would be the head, wasn’t as unpopular as might have been thought. In fact, many people supported what he was doing.

Whilst some of the monks in the monasteries did lead very ‘Christian lives’, many lived in somewhat luxury and owned vast buildings and areas of land. Many monks were indeed regarded as being ‘fat and indolent’, and so clearly didn’t like what Henry was doing and stayed loyal to the Pope.

Henry wasn’t one to lose! In the face of their opposition, he simply decided to close down the monasteries – and those monks who protested were simply despatched (often quite horribly) to an early grave. This was called the Dissolution of the Monasteries – and it meant that those Catholic monasteries and the church buildings and various estates who refused to acknowledge Henry as head of the new Church of England and continued to stay loyal to the Pope, were closed down. They were literally ‘dissolved’.

Some of what happened during this period was extremely unfair. Henry despatched his officials to visit the monasteries to gather evidence of their disobedience … but many of the reports that Henry received back were simply written accounts of what the officials knew Henry wanted to hear … so there was a lot of unfairness, corruption and often ‘damn right lies’ going on. Indeed, for going against Henry and his new law, many Catholic religious leaders and even lowly monks and lay priests were accused of treason, the punishment for which was invariably a particularly gruesome death.

Some of the now empty monasteries were demolished and the stones they had been built with eagerly acquired by the local population to build houses, whilst others were sold off remarkably cheaply, often to the very same officials who had visited them and given false witness to Henry about the activities that had been taken place there.