Updated: 17 October 2023 |

|

Length: About 2¼ miles |

|

Duration: Around 3 hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

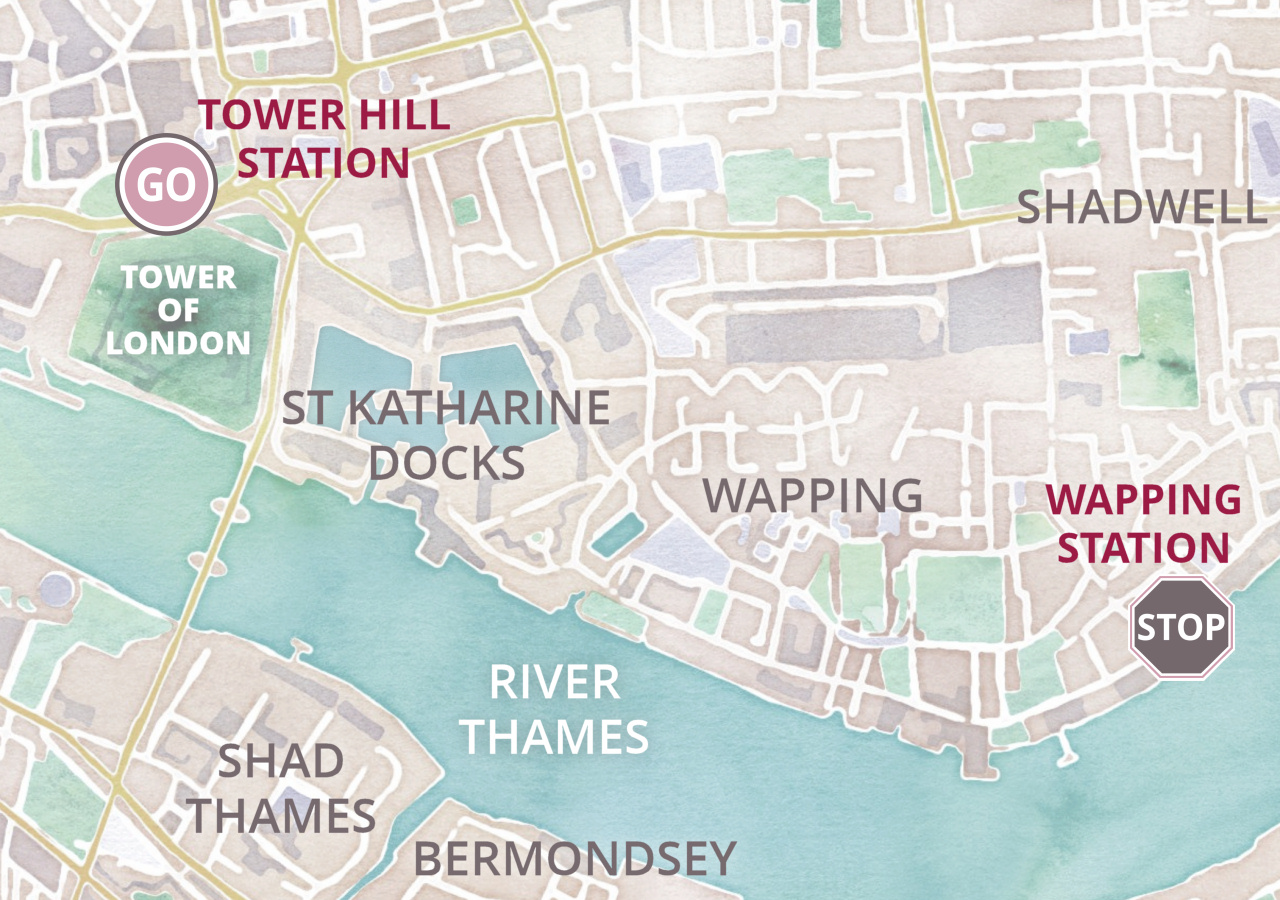

A walk from Tower Hill to Wapping

NOTES

- This walk can be treated as the first leg of a five-hour walk from Tower Hill through Wapping and Limehouse to Canary Wharf. The introduction below takes in both halves of the full-length walk. For the second leg, please click here.

- Whilst it may be obvious, I must point out that things might have changed since I wrote this walk. This is particularly the case with the Thames Path – access points that were previously open can suddenly close, particularly when building work is taking place. London, and the riverside in the docklands in particular, are continually changing, so buildings and sights described may differ. As always, I appreciate any comments or suggestions from those who do the walk, particularly about any changes that have taken place so I can keep the walk updated. Please use the Contact page to do this. Thanks.

Start: Tower Hill station |

|

Finish: Wapping station |

GETTING HERE

The walk starts at Tower Hill tube station – which is on the Circle and District lines.

Buses

Number 15 stops adjacent to Tower Hill Underground station, opposite the Tower of London. The service runs from Trafalgar Square/Charing Cross station, St Paul’s Cathedral, Bank station/Queen Victoria Street and Monument station. (For details of other nearby bus routes check the Transport for London website.)

INTRODUCTION

The walk takes us eastwards from Tower Hill in the direction of Canary Wharf, passing through the once busy, but sadly always poor, riverside communities. The major industry was once shipbuilding, but later it became part of the world’s busiest port and largest complex of docks.

Since Roman times the river’s importance to London, and indeed the rest of Britain, was immeasurable, which unfortunately meant that during the Second World War it became a strategic target for the German Luftwaffe bombing raids. Indeed, there was a period of a couple of months when the bombing raids were targeting the docks and London’s East End virtually every night – and sometimes during the day as well. This resulted in vast areas of the docks, warehouses and factories, as well as the homes of tens of thousands of the people living there, being destroyed and, of course, huge numbers of deaths and casualties.

Whilst some reconstruction took place after the war this only went so far, and by the 1960s and early 70s, the number of ships coming here to unload significantly diminished.

This was a result of two things. The first was the continual labour disputes that had dogged the Port of London for many years, often resulting in bitter strikes. Much of this was caused by the shocking way the dockworkers were treated; their working conditions and pay were a constant source of justifiable grievance. The second was the advent of containerisation. Cargoes were increasingly being carried in containers which were loaded on to ever bigger ships that could no longer navigate the River Thames. So instead they were using purpose built ‘container ports’ at places such as Tilbury, further down the Thames estuary, Felixstowe or Southampton.

The result was that by the early 70s most of these riverside docks had closed, and these previously busy communities began to become almost ‘abandoned’. Many of the local people were being rehoused by London County Council in new towns further to the east of London and in Essex. In addition, there were many buildings damaged or destroyed during the bombing raids that had not been rebuilt. All of which resulted in areas of Wapping and Limehouse, for example, becoming rather sad and desolate looking.

However, it wasn’t long before a few ‘brave’ property developers (or more likely brave speculators) began to realise that some of these now derelict riverside buildings had potential for residential use.

It took a while to catch on, but by the 90s these previously abandoned and neglected warehouses alongside the River Thames – and of course in Canary Wharf and elsewhere on the Isle of Dogs – have either been renovated and turned into trendy apartments or demolished with new residential blocks built in their place.

During the walk we will see glimpses of what the area would have looked like many years ago, as well as examples of both questionable and sympathetic post-war architectural redevelopment. Sadly, preservation was not exactly top of the list of priorities for the local authorities planning departments at that time, but fortunately, more recent interest in preserving what’s left of the past has meant that preservation orders have been put on many surviving buildings and the style of more recent redevelopments has generally improved.

STARTING THE WALK

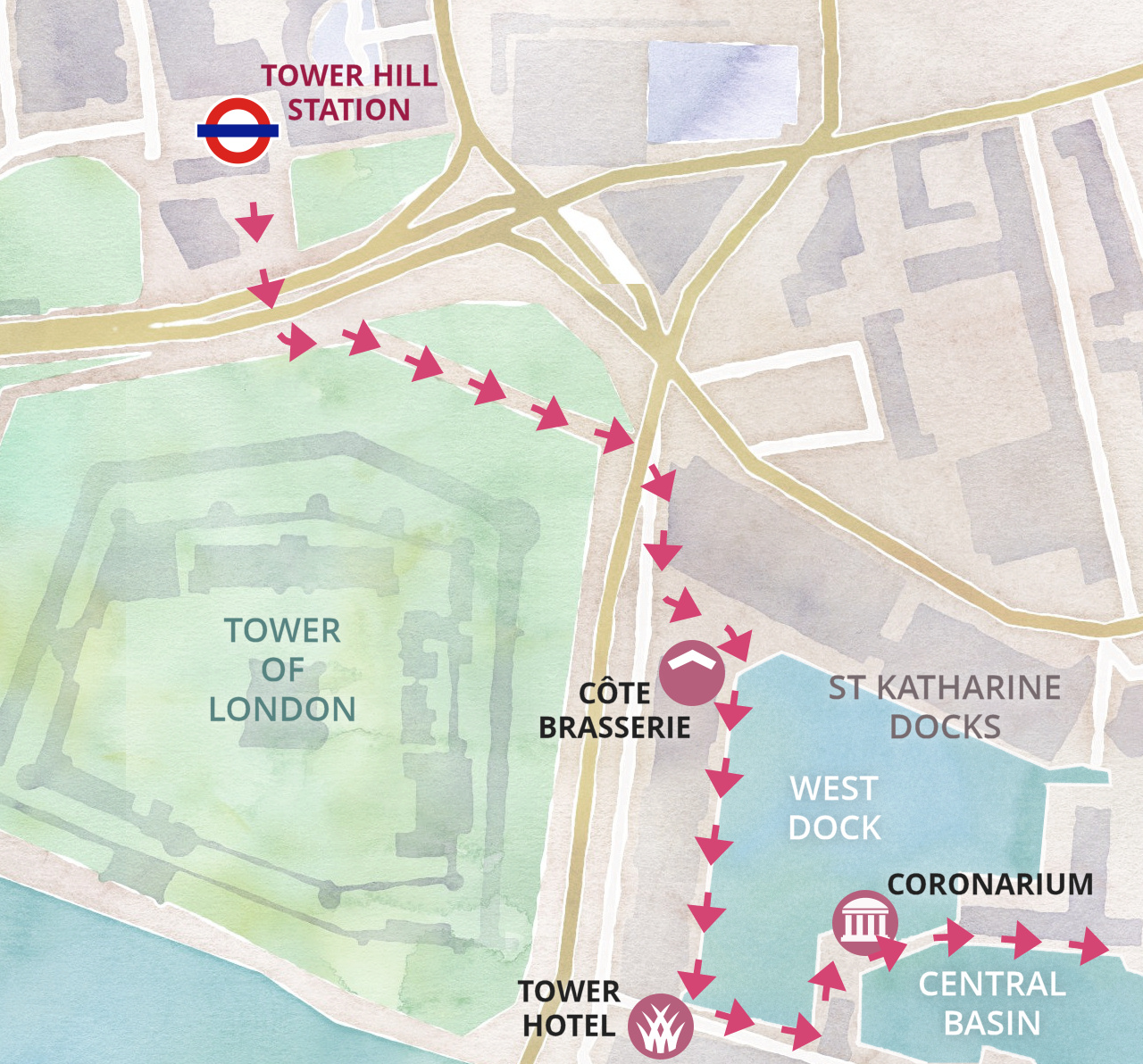

Upon arriving at the station exit through the ticket barrier, turn left and walk down the steps on the right, passing the lower entrance to the station, and continue towards the underpass. (However, if you leave the platform via a different exit and emerge from the newer entrance/exit then simply turn right and walk down the steps.)

As you walk down the steps, the statue you pass on your left is believed to be of the Roman emperor Trajan (98–117 AD) and behind it are parts of the original Roman wall that at one time encircled the City of London.

At the end of the underpass you pass the remains of the only surviving medieval ‘postern’ gate, which is thought to date back to the 13th century – a postern being a secondary or hidden gate, its whereabouts known only to occupants of the castle, or in this case the Tower of London.

Turn left along a pleasant path, with flowers and shrubs in the raised beds on the left and the grass moat of the Tower of London on your right. Pass the steps that lead up to the Tower Bridge Road and walk through the underpass, then turn right, passing the unusual ‘glass and scaffolding effect’ frontage of the Tower Bridge House office building.

This brings you out into the St Katharine Docks West Dock, one of the three original basins. The original warehouses on the left were demolished in the 1960s and it is now lined with restaurants you see in front of you, with offices above.

On your right you’ll see the Côte Brasserie – walk down the ramp alongside it that leads to the pontoon.

(NB – If for any reason the steps beside the Côte Brasserie and the path along the pontoon is closed, then instead simply walk straight ahead, past the line of other restaurants on the quayside and take the next turning to the right in front of the Ivory House. Pass the home of the touristy Medieval Banquets venue and at the end of the passage you will see the ‘Coronarium’ on your right – turn left and pick up the walk from here).

The enormous brick building on your right, with the large pillars is International House. This 1970s office and residential development was built to a similar design and size of the warehouse that it replaced, which gives you an idea of how huge those 19th century quayside warehouses were.

There are usually several traditional Thames sailing barges and as well as Dutch barges moored alongside the pontoon.

St Katharine Docks are built on the site of the ‘Royal Hospital and Collegiate Church of St Katharine by the Tower’ which was built around 1148 by Matilda, the wife of King Stephen, in memory of her two children who had died. It was to provide for a ‘Master, brethren, sisters and thirteen poor persons’, and built on land in the parish of St Botolph without Aldgate, bought for that purpose from the priory of Holy Trinity, Aldgate. For its maintenance the Queen gave the hospital a mill near the Tower of London and the land belonging to it.

It was later ‘endowed’ and granted a Charter, which reserved its patronage ‘to the Queens of England for ever’, and our Queen Elizabeth II is still a patron to this day. Its history is fascinating – it’s a ‘Liberty’ and a ‘Royal Peculiar’ – and has now relocated its ‘Mission’ to Limehouse.

Anyway, for the next 700 years it was both a religious community and hospital for people described as ‘undesirables’. These were people who weren’t allowed inside the City of London and so lived as close as possible to it. Despite the great number of people living in and around it, in 1804 the site was chosen for the building of the St Katharine Docks.

As we discover later in the walk, with the rapid increase in the number of ships bringing cargoes into London and the lack of space along the banks of the Thames to unload them, together with the enormous amount of theft taking place, ship owners and merchants had begun to open ‘inland’ docks. The first were at Wapping and on the Isle of Dogs and were so successful that more were needed, especially closer to the City of London, hence the choice of St Katharine.

This resulted in the church and the hospital, together with around 1,250 houses (or more commonly hovels) being demolished, making over 11,000 people homeless. Sadly, they were given no compensation or help in finding anywhere else to live, putting even greater pressure on the problem of homelessness in London at that time.

(For those interested in the history of St Katharine’s there is some excellent information at British History Online, sourced from the Victoria County History of London.)

At the end of the pontoon turn left along Cloister Walk, passing the colourful murals on the rear wall of the 15-storey, 800-room Tower Hotel. It was built in the 1980s and I find it ugly (and that’s not just my view – it has twice been voted the ‘second ugliest building in London’.)

Don’t walk through the ‘arch’ under the building ahead, but turn left, (keeping the basin on your left, with a good view back across the West Dock).

Immediately in front of you is a most unusual structure – for some years a Starbucks coffee shop, then a noodle restaurant, then Azimut Café from 2021. It’s presently awaiting a new tenant. The building was originally the ‘Jubilee Coronarium’ and despite its classically inspired design it was only erected in 1977. Designed as an open-sided ‘chapel’ to celebrate the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, its eight Doric columns were salvaged from one of the warehouses that were pulled down during the docks’ redevelopment. Interestingly, it’s said to be on the site of the original Church of St Katharine that was demolished when the docks were built.

However, don’t walk on yet. Turn around and look at the wall of the building behind you, where above the cash machine you can see the ‘translucent block’ that was the original monolith created for Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film ‘2001 – A Space Odyssey’. It had been carved out of a solid block of a type of acrylic, but when Kubrick saw it he felt that its transparency didn’t “add to the film’s mystery”, so he asked for another one to be made and this was carved from black basalt that came from Scandinavia. However, the original was never destroyed and was eventually discovered in Elstree Studios. A London-based Bratislavan sculptor bought it and when he was later commissioned to make a sculpture for the 1977 Queen’s Silver Jubilee celebrations, he carved a crown into the block.

Following its unveiling by Her Majesty the Queen on 5th June 1977, it was put on display here in the Coronarium and was moved to its current position in 2000. The plaque on it reads –

The Silver Jubilee Crystal Crown was sculpted on this site by Arthur Fleischmann KCSG, FRBS, MD, who pioneered carving in Perspex. The block measures 10’9” by 5’9” by 8” thick and weighs two tons. It is the largest solid block of Acrylic in the world. It was originally made in 1968 for Stanley Kubrick’s film “2001 – A Space Odyssey”, but was rejected by the director in favour of the now famous black basalt monolith.

After the Coronarium, walk across the lift bridge and continue on past the row of cafes and restaurants. Half way along there’s a passageway that leads to public toilets and back to the Commodity Quay, the alternative route if the ‘pontoon pathway’ is closed.

Cross the footbridge over the entrance to the East Dock – notice on the left Thomas Telford’s original 1828 footbridge, whilst on your right the large anchor was salvaged from a Dutch ship called the ‘Amsterdam’, which sank off the coast of Hastings some 200 years ago.

Before you walk on, take a look back at the building you’ve just walked past. Called the Ivory House because this is where vast quantities of ivory were unloaded and stored, it’s the only original warehouse left in St Katharine Docks, most being badly damaged or destroyed in the Second World War. And quite amazingly, it still has its original rooftop clock.

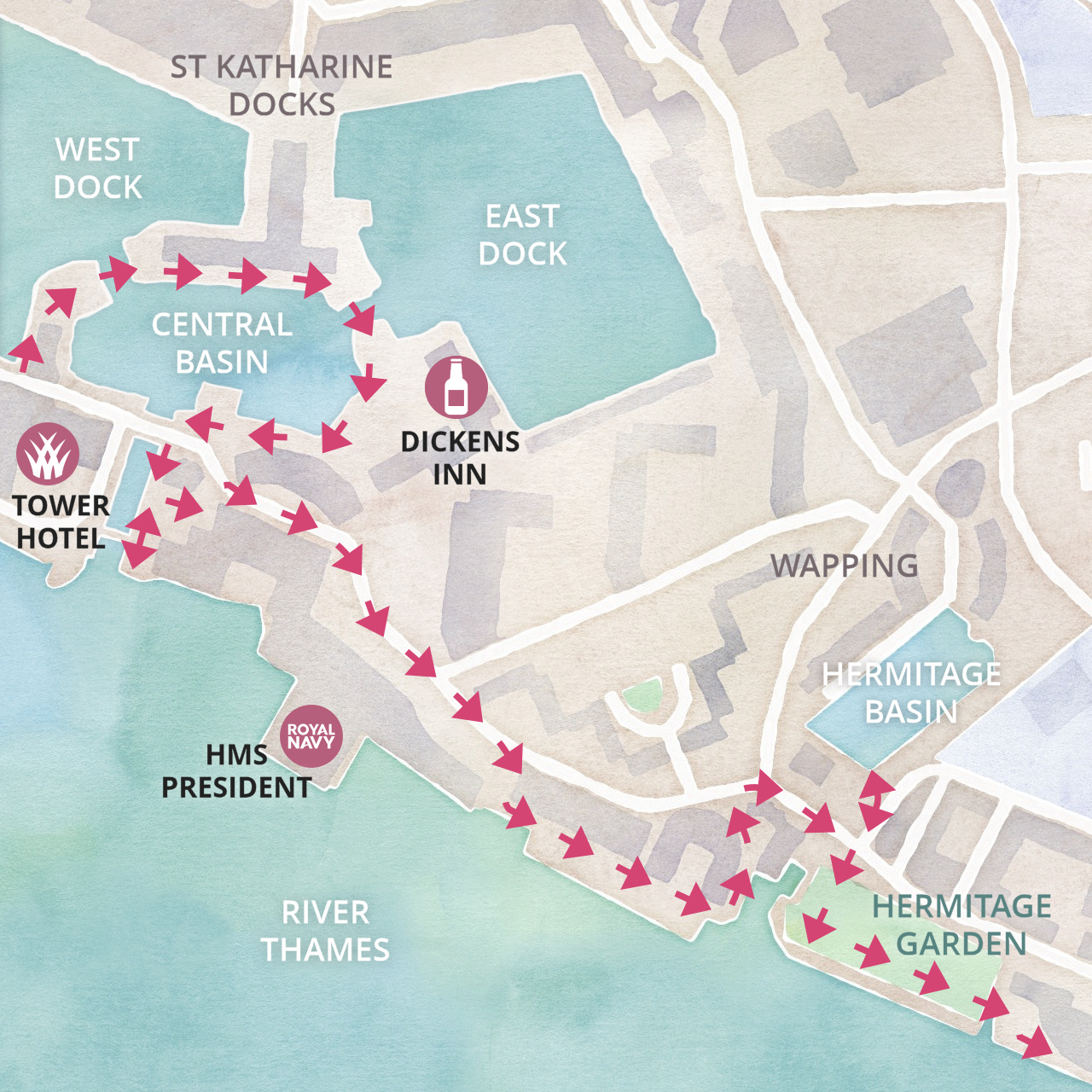

Walk on now passing the Dickens Inn, a highly popular tourist destination that in summer is festooned with floral displays.

On your right you may see a ‘golden boat’ moored – this is the ‘Gloriana’, the Queen’s Row Barge which was built for her to sail down the Thames in as part of her Golden Jubilee Celebrations in 2012. It celebrates the Commonwealth by having the crests of sixteen Commonwealth countries along its sides.

Built in 1973, the Tower Hotel steps down from 15 storeys in each direction around what I have heard described as a ‘staggered cruciform’ plan, whatever that means. Whether or not it’s because of its 1970s design and (despite its stunning location) surprisingly small bedroom windows, it has now become more of a ‘package tour hotel’, rather than the prestigious establishment it once was.

After the large Indian restaurant is an unusual cream coloured ‘crescent-shaped’ three-storey building with pillars – we see the other side of it shortly and I’ll mention more about it then.

Continue alongside the basin to the end of the path and ahead is another view of the Tower Hotel. Walk towards the hotel, but don’t cross the bridge – instead turn left down to the right of the Dock Office and walk alongside the entrance lock that leads in from the Thames. You can see how narrow it is – as I’ve already explained this was partly responsible for the decline of these docks as the ever-increasing size of ships could no longer enter.

On the left of the lock is the old Dockmaster’s House, now a private residence. (And just in case this path is closed then use the road bridge to cross over the lock.)

The view from here is simply iconic, and for an even better look at Tower Bridge, cross over the bottom gate of the lock. Behind the bridge, on the other bank, you can see the unusually-shaped glass City Hall, the head offices of the Greater London Authority and base for its elected Mayor. Directly across the river from where you are standing is the enormous ‘Butlers Wharf’ building, once again previously warehouses but now very trendy apartments and with some excellent (and again expensive) restaurants on the river’s edge in front. But that’s the South Bank and another walk for another day.

Just to your left downstream is a Royal Naval base called HMS President (more on which shortly) and from its pier the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh ‘took the salute’ as the flotilla of ships passed by during her Golden Jubilee Thames Pageant.

Retrace your footsteps but halfway along the side of the lock walk up the steps alongside the Dockmaster’s House and at the end of the passageway turn right. On the other side of the road you can see the other side of the crescent-shaped building we saw just now. This unusual and perhaps classical-looking three-storey building is actually a row of private houses called Tower Walk. The architects took the inspiration for it from a terrace in extremely upmarket Regent’s Park and, although a nice building, I feel it is somewhat out of place here.

![]()

You are now in St Katharine’s Way. Turn right past Devon House, built on the site of a bomb-damaged warehouse in 1987 and recently refurbished, whilst next to it is the ‘shore-based’ HMS President, named after a First World War ship. (Naval land establishments like this are also known as ‘Stone Frigates’.) It is the largest Royal Naval Reserve unit in the country and provides a permanent Royal Naval presence in London, as well being the base of the Naval Regional Command Centre for Eastern England, the University of London Royal Naval Unit and the London Sea Cadets. It has its own quayside and jetty and was previously used as the London terminal of P&O’s jetfoil service.

Like many of the streets along the riverside, St Katharine’s Way was once lined with warehouses, but many were damaged or destroyed during the Second World War and subsequently rebuilt as offices or apartments. Unfortunately, as I mention again later in the walk, for many years town planners often appeared to turn a blind eye when it came to the rebuilding or renovation of many of these old warehouses, but an exception is certainly Millers Wharf that adjoins HMS President. Originally built in 1865 and restored in 1989, its frontage has been cleverly designed to look more like the warehouse it replaced.

Between Millers Wharf and the adjacent building is a small passage, which as the sign says is Alderman Stairs.

Next to Alderman Stairs turn immediately right between the buildings. It’s signposted ‘Thames Path’ and leads to a broad raised terrace (with steps up a little further down, so no need to climb the wall!) From here there is a wonderful view looking back up the Thames to Tower Bridge and across to the huge Butlers Wharf. As previously mentioned, these were once enormous warehouses but now trendy apartments. The small white building between the two Butler’s Wharf buildings was once a banana warehouse before becoming Sir Terence Conran’s Design Museum, which he opened in the late 1980s. The museum has now moved to Kensington. Just a little further to the left you will see the narrow outlet where the Neckinger River flows into the Thames; it was once the site of the small St Saviour’s Dock. The Neckinger is one of the Thames’ many tributaries – this one rises in nearby Southwark. Immediately beside and behind it was once one of London’s notorious slums, known as Jacob’s Island. It was immortalised in Charles Dickens’ book ‘Oliver Twist’ as the place where Bill Sykes, the principal villain, came to a horrible end in the mud of Folly Ditch.

The building behind you, now apartments called Tower Bridge Wharf, was once a six-storey warehouse that stored cargoes including wine and tea. On the quayside here fruit and vegetables were unloaded, to then be taken by road to the Covent Garden Market.

Walk to the end of the terrace and follow it around to the left – but first look over the wall and you can see where one of the original lock entrances used to be. (I explain more shortly.) On the other side the large Dove sculpture is in the Peace Park, which we see shortly.

The path brings you out at the end of St Katharine’s Way – and we turn right into Wapping High Street.

However, the road running straight ahead is Thomas More Street, which used to divide St Katharine Docks from London Docks. The street now leads up to a massive new 15-acre housing, retail and leisure complex called ‘London Dock’, not surprisingly built on the filled-in London Dock. It will have over 1,500 homes, shops, restaurants and even its own secondary school. It was on this reclaimed dock where in 1986 Murdoch built his controversial headquarters and print works for his newspapers – The Sun, News of the World, Times, etc. Nicknamed ‘Fortress Wapping’ because of how securely it was constructed – Murdoch knew that when he moved his newspaper operations out of Fleet Street there would be an almighty battle with the trade unions – and he was right of course. This was the scene of some of the ugliest battles in modern time between picketing strikers and those who chose to work. Those wanting to work were bussed in with police escorts and the bitter and violent demonstrations continued on a daily basis for many months. That was in the 1980s, and Murdoch has since moved the printing presses again, hence the new developments on the site.

As you turn right, you see the old single-storey brick building, which was once the hydraulic pumping and impounding station that kept the water levels in the docks at a constant level.

The road crosses a ‘bridge’ over the disused lock entrance we saw just now, which led into the Hermitage Basin, providing one of the two entrances into London’s Western Docks that was built in 1805 – we see the other one shortly. This entrance closed back in 1910.

Having crossed the bridge we’re going to make a short diversion – turn to the immediate left, between the original brick pillars that were once the entrance for the dock workers. Once inside you can appreciate the effort that has gone into preserving part of this basin. Walk to the top, where on the left you’ll see a fascinating ‘rope sculpture’.

The end of the basin is a stepped terraced garden that leads down to what is now known as the ‘ornamental canal’ – cross over the road for a better look. Notice how much lower the canal is than the basin; this is because the basin was once 30 feet deep, but to make it safer it was partially filled in and the water is now less than two feet deep.

The original canal was once a broad waterway channel that allowed ships access through to Tobacco Docks and the Shadwell Basin that we see more of this later in the walk. I do think that the architects and planners have done an excellent job of redeveloping this part of the docks without completely losing any connection to what it once looked like. Even the modern housing developments on either side don’t look too out of keeping.

And the reason for the name ‘Hermitage’? Several hundred years ago there was actually a solitary dwelling (or hermitage) here.

You now need to turn around and head back to Wapping High Street and then cross over into the small riverside park.

This is the Hermitage Riverside Memorial Garden, built on the site of the Hermitage Wharf that was destroyed by massive firebombs on 29th December 1940. The park is a memorial to the terrible loss of life suffered by the people of London’s docklands and East End; they experienced the fiercest bombing of anywhere in Britain in the Second World War. Raids took place virtually every day for nine months in what was known as the Blitz. The Germans realised the importance of the docks to London – and of course to the rest of the country – so it became their number one target. (The word ‘Blitz’ comes from the German word Blitzkrieg, meaning ‘lightning war’ – the Germans believed that such intensive bombing on London’s docks and its East End would quickly bring about Britain’s surrender. However, they clearly underestimated the spirit of London’s East Enders as despite the Blitz lasting for nine long months – from September 1940 until May 1941 – there was never any thought of surrender. (And to put it into perspective, I have read that over 25,000 bombs exploded in this small area of London alone.)

The Dove sculpture was designed by Wendy Taylor CBE, the dove signifying hope and peace, whilst the empty space in the centre commemorates those who died.

The view up and down river from the garden is lovely. It is a great place to pause and imagine what life must have been like for people living and working here during that horrendous period. The garden itself is a testament to people power – developers wanted to build yet more apartment blocks, but the local people campaigned for years for a park to be built instead. What was eventually created was much smaller than they had wanted, but at least there is a garden.

Walk through the garden alongside the river, passing the boats and sailing ships in the Hermitage Community Moorings. Keep on the riverside path as it continues along a broad promenade, passing the large Smith’s Fish Restaurant on the ground floor of the first apartment building. With its floor to ceiling windows it always looks an attractive place to eat, but whilst the menu looks excellent, I still haven’t tried it.

Three huge apartment blocks follow – West, Central and East Tower – fairly bland buildings but with interesting sloping roofs and balconies, which do appear to vaguely resemble those of a cruise liner – or am I being too optimistic?

At one time each section of the quayside’s wharves and warehouses specialised in specific cargoes and this stretch was predominantly spices. On the other side of the adjacent Wapping High Street many of the apartment buildings were built on the site of those spice warehouses and have been named after the islands where the spices came from – Sumatra Court, Java Court and Zanzibar Court, for example. And until only a few years ago you could sometimes still smell various spices in the air when you walked past.

The promenade now narrows and looks as though it comes to a dead-end, but it doesn’t, and it takes you back onto Wapping High Street. Where the passage turns to the left is another set of stairs – these are blocked off now, but were called the ‘Union Stairs’, and once gave access to the original Turk’s Head Inn, which as I explain later was where pirates and mutineers who had been condemned to be hanged at the nearby Execution Dock were allowed to stop for their ‘last quart of ale’.

Turn right back down Wapping High Street – which must surely be the only High Street in Britain without any shops. It did once have thirty-six pubs – but now there’s only three left. The street was built in the 1500s to link the riverside quays with the City of London and was described in the 16th century as a ‘filthy passage, with alleys of small tenements and cottages … whose many inhabitants were victuallers who supplied sailors with maritime equipment and just as importantly cheap alcohol and women’.

This next stretch is one of my favourite parts of the walk. Ahead you see what looks as though it might have been a bridge, which indeed it was. Known as the Wapping Pier Head, this was the second entrance lock through which ships entered the London Docks complex. Once again, the lock is now filled in and been turned into a delightful garden for the private use of the residents of the lovely Georgian terraced houses on either side.

These were designed in 1812 by D.A. Alexander, the surveyor and architect of the docks, as homes for the managers of the London Dock Company. Take a walk for a couple of yards up the paved access road in front of the terrace facing you (it’s marked to ‘Pier Head 4½–10’), which enables you to fully appreciate just how beautiful these old Grade II listed houses are. These were among the first riverside buildings in the area to be turned into luxurious homes and I recently saw an advert for a two-bedroom apartment in one of the houses for one and three-quarter million pounds!

Immediately after the Pier Head is the Town of Ramsgate, a very old inn that’s one of the few survivors of the 36 that were once along this street and which catered for the dockworkers and warehousemen as well, of course, as the sailors.

It’s definitely worth taking a look inside – (they are used to people popping in to do so) – and as you’ll see it’s small and narrow with lots of wood panelling that gives it an even more ‘historic’ feel. There’s a little terrace at the rear where you can enjoy views across the river.

Originally called the Red Cow (apparently after the distinctive hair colour of one of the early barmaids) the name was changed to the ‘Town of Ramsgate’, the name of a ship that used to sail here from Ramsgate in Kent to unload its cargo of fish, dairy produce and grain. It was always a popular inn for sailors – Captain Bligh and Fletcher Christian enjoyed a drink here before their last ever voyage. The pub’s cellars have had a gruesome history; convicted criminals were kept here before they were hanged, whilst a little later those same cellars were used to hold convicts before they were loaded on to ships for transportation to Australia.

But before or after you go inside the pub, take a look down the tiny alley next to it. These are the renowned Wapping Old Stairs. If the tide is out, then you can walk down to the pebble beach beneath the pub – but be careful – the steps are deceptively slippery and can be treacherous thanks to a mixture of slimy mud and algae. If you do gingerly make your way down, then notice the noose hanging from the rear of the pub.

Another notable event in the long life of the pub was the capture here of the infamous ‘Hanging’ Judge Jeffreys, much hated due to his habit of giving extremely harsh sentences to those he tried in court. He was said to have been responsible for the hanging of many men here. He had also presided over the courts in a number of towns in south-west England during the ‘Monmouth Rebellion’, when loyal Protestants tried to overthrow the Catholic King James II. (It was called the Monmouth Rebellion because it was led by the Duke of Monmouth, an illegitimate son of Charles II.) Jeffreys sentenced hundreds of men to death and many others were sentenced to transportation.

However, he had his comeuppance here when he was caught trying to escape retribution following the 1688 ‘Glorious Revolution’ when James II himself was overthrown. Unfortunately for him, Judge Jeffreys had ‘backed the wrong side’ and was attempting to board a collier en route for Germany in an attempt to escape from his own death sentence when, arrogantly and stupidly, he went into the pub for one last glass of ale. Despite being in disguise he was soon recognised, captured and taken to the dungeons of the Tower of London.

There is an excellent account of Jeffreys’ capture in the Walter Thornbury’s fascinating book ‘Old and New London’, which was published in 1897 and I have put it in the appendix.

Someone else captured here whilst trying to escape by ship was Thomas ‘Captain’ Blood, the Irishman who in May 1671 was found in possession of the Crown Jewels he had stolen earlier from the Tower.

Time to stop for a snack?

The Turk’s Head may still look like a pub but it’s now an excellent café and a great place to stop for a coffee, sandwich or even a more substantial lunch.

Time to stop for a snack?

The Turk’s Head may still look like a pub but it’s now an excellent café and a great place to stop for a coffee, sandwich or even a more substantial lunch.

Immediately opposite the pub is a gate leading into a small garden cemetery that once belonged to St John’s Church in the adjacent Scandrett Street. Walk through it across into Scandrett Street and just to the left you’ll see the Turk’s Head.

Leave the Turk’s Head and start walking back up towards Wapping High Street, passing the St John the Baptist Church. Now no longer a church and converted into apartments, it was built in 1617 as a ‘chapel of ease’ to St Mary’s Whitechapel. (A chapel of ease is a building that’s not actually a church, but where people can worship, and which is under the jurisdiction of a parish church). However, in 1694 Wapping became a separate Parish and therefore required its own Parish Church so in 1756 St John’s was rebuilt and enlarged. It was badly damaged in the Second World War, with only its tower and the shell of the church left standing and was never rebuilt. Interestingly, the tower was built of an unusual combination of coloured stone and brick, carefully chosen to be visible by ships sailing up the Thames in foggy weather to aid their navigation. It was clearly well-enough constructed to have survived the bombing that destroyed the rest of the church.

Next to it is an 18th century charity school building that has also been converted into apartments. Founded in 1704 for fifty boys and forty girls, there are two lovely Coade stone statues, one of a boy and one of a girl, both in colourful uniforms, above the entrance – and in case there’s any doubt as to which should be used, the words ‘Boys’ or ‘Girls’ are carved above. The adjacent building has the words ‘infants’ above one door and ‘boys’ above the other, so presumably it was built before education for girls was properly accepted.

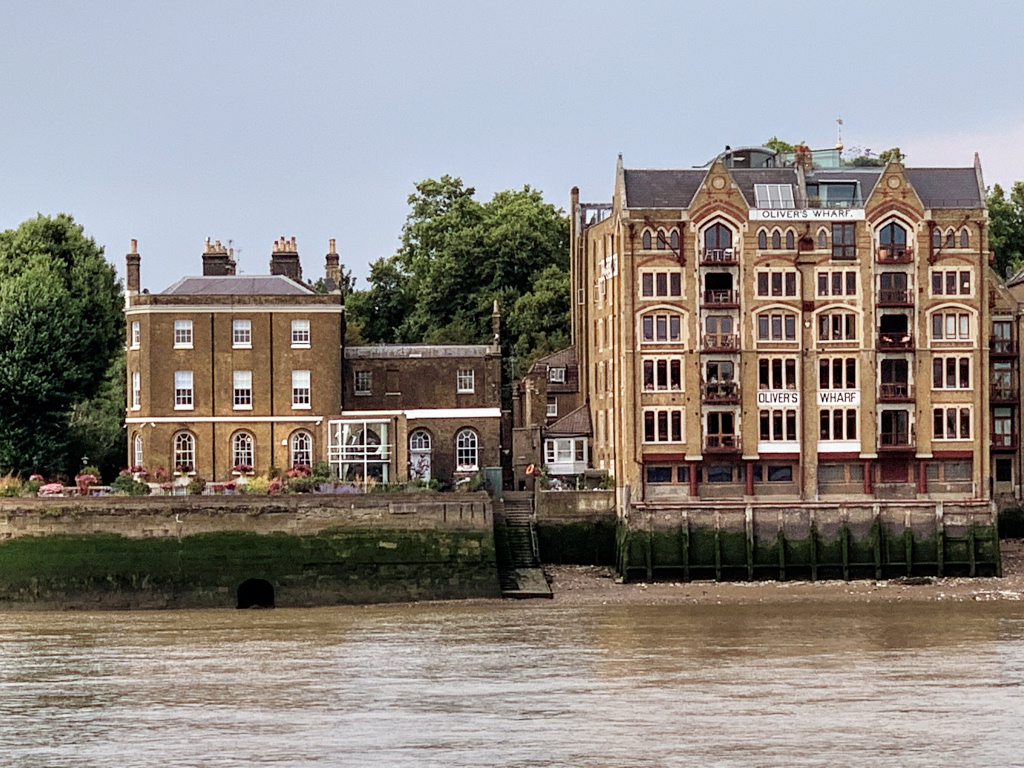

Walk back up to Wapping High Street and turn left. On the other side of the road at Number 64 is Oliver’s, a former tea store and one of the first warehouses to be converted into luxury apartments. (American singer Cher was an early resident.) The building next door was built for social housing, something much needed within the area, but I can’t help wondering whether more thought have gone into its design and construction to make it a little more attractive and in keeping.

Pierhead Wharf was built in 1996–7 in place of a Victorian warehouse and in the style of the surrounding survivors. An extra floor with four penthouses was added in 2003.

The St John’s Wharves warehouses on either side of the street have been well preserved, and a notable feature are the overhead gangways that once enabled porters to transport goods from one warehouse to the other.

Then comes a most unusual 1970s building with weird fibreglass shapes that I’ve heard some call a ‘monstrosity’, whilst others ‘a wonderfully creative abstract concrete building’ – but I have to say to my mind it’s just ugly and totally out of place. (Having said that, the estate agent’s office opposite could easily win an award for inappropriate design in an historic street.) Somewhat surprisingly, it is the maintenance yard of the Metropolitan River Police, where their patrol boats are repaired and stored. The actual river police station is just a few hundred yards further on.

Turn right into the Waterside Gardens. This was the site of the notorious Execution Dock that I mentioned earlier, where for more than four hundred years pirates, smugglers and mutineers who had been sentenced by Admiralty Courts were hanged. (The Admiralty Court was responsible for trying and convicting those who had committed offences at sea and had been bought back to London to face justice.) The ‘dock’ consisted of a scaffold – and in order for the condemned man to suffer as much as possible there was no ‘trapdoor’, so death was often by slow strangulation. It was then the custom for the bodies to be left hanging here until three tides had washed over them, making them clearly visible for all to see, so as to act as a deterrent to other potential pirates or smugglers. Not that it seemed to have much effect though!

‘Hanging events’ were a great attraction for locals – the condemned man would arrive in a cart, accompanied by senior officers from the Admiralty. Custom had it that he would be allowed to stop for a last quart of ale and, as already mentioned, that often took place at the Turk’s Head Inn just a few hundred yards up river.

The last execution was said to have taken place here in 1830, but one of the most infamous of all pirates to be hanged here was Captain Kidd, which took place in 1701, and his name lives on in the pub that we come to shortly. (Captain Kidd was said to have provided the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s adventure novel Treasure Island.)

Alongside the Gardens are the Wapping New Stairs, but it’s not advisable to attempt to go down, as the steps suddenly end in a vertical metal ladder!

From the Waterside Gardens you can look downstream and see the pier used by the River Police – and if you look carefully you can see the blue lamp still hanging nearly half way along – at one time these were hung outside all police stations. Next to the pier is the actual Metropolitan River Police station. Now called the Marine Policing Unit, it was built in 1909 on the site of the very original station. The station is now closed to the public, but if you walk up the little passage to the right you can see another original blue lamp still over the door.

To the right on the opposite bank of the river you can see a little group of trees in a short stretch ‘green area’ known as Cherry Gardens. For several hundred years this was a popular place to take a stroll and admire the river views and, in his diary, Samuel Pepys recorded visiting the gardens to buy cherries for his wife. And it was from here that J.M.W. Turner got the inspiration for one of his most popular paintings – The Fighting Temeraire, (the famous ship that took part in the Battle of Trafalgar) being towed by steam tug to the breakers yard in Rotherhithe. Nowadays the Cherry Garden Pier is the base for the City Cruise pleasure boats. Just to the left of it is the historic Angel pub, and to the left of that the old ‘leaning’ building was once the base of the last company of lightermen to operate on the Thames. To the left of that was once Edward III’s manor house, whilst further to the left you can see the spire of St Mary’s Church, Rotherhithe.

Next to the police station are the Aberdeen and St John’s Wharfs, two more well-restored buildings with plenty of authentic (looking!) features, whilst on the other side of the road is another park, the Wapping Rose Garden.

The Captain Kidd pub may look very ‘olde worlde’, but it certainly isn’t. It’s named after the infamous Scottish privateer, William Kidd, a onetime naval officer who after being sent to catch pirates turned to piracy himself. As I mentioned before, he was hanged at Execution Dock in 1701 having been convicted of piracy and murder.

Whilst the actual building dates back to the 18th century, it was originally a warehouse that stored coffee, dried fruits and bales of wool from Australia, and was only converted into a pub in the 1980s. It is a fascinating place all the same. I love the narrow courtyard entrance – notice the noose hanging over the entrance door – and besides the spacious bar on the ground floor there is also the Galleons Reach restaurant upstairs. Best of all though is its terrace that overlooks the river, arguably the biggest along this stretch of the Thames. So even if you don’t fancy having a drink it is worth a quick visit. Looking from the terrace of the Captain Kidd to the other side of the river, you can see the sign saying ‘Thames Tunnel Mill’ on a former 19th century flour mill that until the 1970s was producing flaked rice and tapioca (which brings back horrid memories of the puddings served for school dinners).

Behind it is the historic Church of St Mary’s in Rotherhithe, famous for its connections with the Pilgrims’ ‘Mayflower’ sailing to America.

Continuing on, next to the Captain Kidd is Phoenix Wharf, one of the few warehouses that actually appears to be original and not modernised, and still with the ‘hauling’ doors on each level where goods would be hoisted up on pulleys for storage. Rather unusually, not many of the buildings on this short stretch appear to have been so badly damaged or destroyed in the war – photographs taken pre-1940 show very little difference to the structures you see today.

Alongside it are the King Henry Stairs and a narrow walkway leading to ‘Wapping Pier’. The gate leading to it is locked and is the base of the Silver Fleet Thames Cruisers.

Almost opposite is the architecturally interesting New Tower Building. Built in 1886 by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company, it’s adjacent to a small piece of land that for some reason until now hasn’t been built on, although it seems that’s about to change as planning permission has been granted for the site to be developed, so building work may be underway when you visit.

Finish: Here, optionally |

There are two places where the walk can be finished – this is the first, so if you’re out of time (or energy) then you can end your walk here.

To do so, simply carry on walking down Wapping High Street for five minutes, passing the enormous restored King Henry’s Wharves and Gun Wharves. These were so named because this was where Henry VIII built a foundry to make cannons for his navy. Although now converted into luxury apartments, once again the exterior of these huge warehouses appear to have retained their original facades.

Continue on, passing Wapping Lane on your left and after a couple of hundred yards you’ll see Wapping station on your right.

GETTING BACK TO CENTRAL LONDON

Wapping station is on the London Overground network (although it is underground at this point).

- To connect with the DLR service to Bank and Tower Gateway take the train from Platform 1 for one stop north to Shadwell, or

- To connect with the underground network then continue on one more stop to Whitechapel and change onto either the District or Hammersmith & City Line.

Trains from here will take you to many parts of central London.

Bus Route 100 will take you from Wapping station back into London. Stops include St Katharine Docks, Tower Gateway station, Bishopsgate, Moorgate station, London Wall/Museum of London, St Paul’s station.

Alternatively, the walk continues a little further (approx. 45 minutes) and visits other parts of Wapping and several particularly interesting features, including Tobacco Dock and the Shadwell Basin. However, it also ends back at Wapping station.

If you wish to carry on, then we’re going to turn left up Brewhouse Lane along the side of the New Tower Building. But before you do, first look ahead down Wapping High Street and you’ll see the enormous King Henry’s Wharves and Gun Wharves, so named because this was where Henry VIII built a foundry to make cannons for his navy. Although now converted into luxury apartments, once again the exterior of these huge warehouses to have retained their original facades.

(Should Brewhouse Lane be closed as a result of the building works, simply continue on down Wapping High Street for a few hundred yards and turn left up Wapping Lane.)

However, if you are able to walk up Brewhouse Lane, then on the left at the top is Tower Building, another block of flats built by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company.

The company was formed in 1863 by Sir Sidney Waterlow. He was a printer and philanthropist, who later became a Lord Mayor of London. The company was a ‘model dwelling company’ – one of a group of private companies set up to improve the housing conditions of the working class by building homes specifically for them. They were not charities and had to ensure that investments in them received a competitive rate of interest. The homes they built were of a higher standard than would normally be built for working men and women, with better sanitation and less overcrowding. The Improved Industrial Dwellings Company was one of the largest and most successful of such enterprises and by 1900 housed 30,000 people.

![]()

Follow Brewhouse Lane around to the right. Chimney Court, the building facing you, is a good example of a 1990s conversion into apartments; it was originally a soap factory. The court’s name no doubt derives from the prominent smokestack located on Green Bank.

At the end of the road turn left into Wapping Lane, a street that’s at the heart of the Wapping community and still has shops such as a traditional butcher (a rare sight these days), a fishmonger, greengrocer, general grocery store, newsagent, pub – and even a Pizza Express restaurant.

Cross Green Bank then take the next left into Watts Street, alongside the little triangle of ‘green’. Notice on the left the carefully renovated blocks of flats (I love the large windows) built originally by an early housing association in co-operation with the local authority.

Directly ahead, on the corner of Meeting House Alley, is the Turner’s Old Star public house, (with the rather unusual view of the Shard beyond, which to me seems strangely out of place here.)

The artist J.M.W. Turner converted two cottages that he had inherited in 1830 into a tavern to be run by Sophia Booth, a widowed landlady from Margate, who was one of his mistresses. He spent much of his time here, particularly as he was fascinated by the River Thames, the source of many of his paintings. However, he tried to keep it a secret, no doubt partly because he was said to have had several other mistresses at the time, so rather than use his own name when he stayed here, he used a pseudonym of Sophia Booth’s name. As a result of his short height and ‘portly physique’ he was soon simply nicknamed ‘Puggy’. Amazingly, the pub is still going strong today, having been renovated in the 1980s.

Walk up Meeting House Alley, which that runs up the right-hand side of the pub, then turn right into Chandler Street and then turn left back into Wapping Lane.

On the other side of the road is St Peter’s, the parish church of Wapping. The entrance is not obvious – it’s through an unusual arched entrance into a tiny courtyard. If the church is open, (it is most days) then it is worth going in to take a look. Whilst it might appear to be a Catholic church, it is actually Church of England, although run by the Society of Holy Cross, an Anglo-Catholic International Society.

Continue on up Wapping Lane for several minutes until you reach the bridge that crosses the Ornamental Canal – the same one you saw back in Hermitage Basin – and directly in front of you is the imposing brick-built Tobacco Dock.

In a dry dock between the ‘canal’ and Tobacco Dock are two sailing ships that are replicas named and designed after real ships. One was the 330-ton Three Sisters, which was built in the dockland’s Blackwall Yard in 1788 and used to sail to the East and West Indies to bring back tobacco and spices. The other was the Sea Lark, an American merchant schooner that was captured by the British navy in 1811. They were installed as part of the plan to create a major shopping and leisure complex here, which I explain shortly.

Tobacco Dock was designed by the London Docks’ architect Daniel Alexander and opened in 1814 as a safe and secure warehouse to store valuable cargoes, such as tobacco, wines and spirits, as well as furs and skins. To me it still looks more like a fortress than a conventional warehouse, which was probably how it was intended to look.

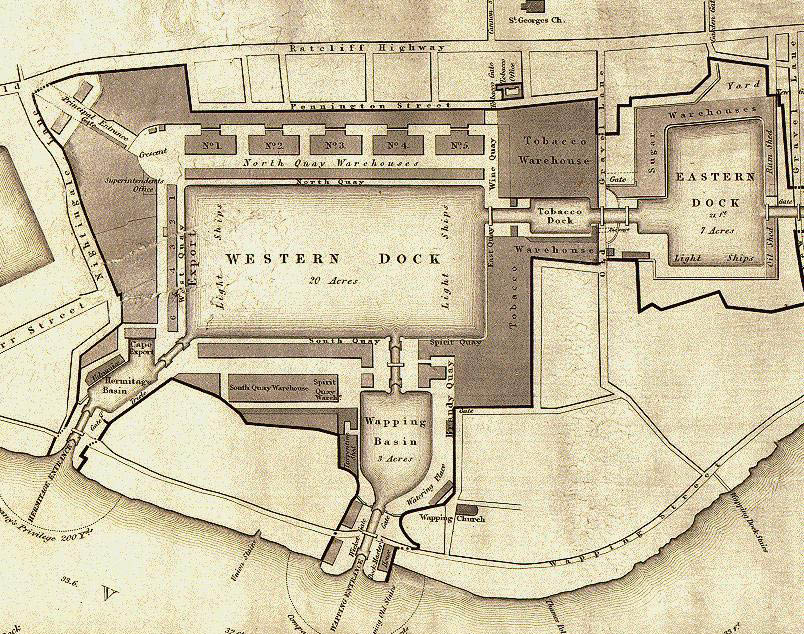

In the plan drawing shown below, Tobacco Dock is the large, almost-square building marked ‘Tobacco Warehouse’. Most of the docks have since been filled in.

By the mid-1830s over 45,000 tons a year of tobacco were being imported from all over the world, which obviously needed somewhere safe, secure and dry to be stored. Inside, huge cast iron pillars were used to support the two storeys and roof as this allowed more space for storage.

Despite its size it survived the war time bombing, but as the docks began to close it became disused and laid empty for a number of years and was going to be demolished. However, in the 1980s it began to be converted into the ‘Covent Garden of the East’, and over £47 million was spent on the refurbishment, which had upmarket shops on two levels. It opened in 1989, sadly just at the 90s recession was beginning and it never took off and was soon closed down.

Fortunately, it is a Grade I listed building, so there are limitations on what redevelopment can be undertaken; English Heritage have said, “We see Tobacco Dock as a future priority because it is too large and important a site to be left standing empty. It is one of the most important buildings in London and if brought back into use it would reinvigorate the whole area.”

Once again there is talk of it again becoming the ‘Covent Garden of the East End’, but this time with hotels and apartments as well as shops. In the meantime, its four acres of space are used for exhibitions – such as the popular gin and craft beer festivals, for conferences and other events and by film companies.

I’ve written a little more about Tobacco Dock in the appendix.

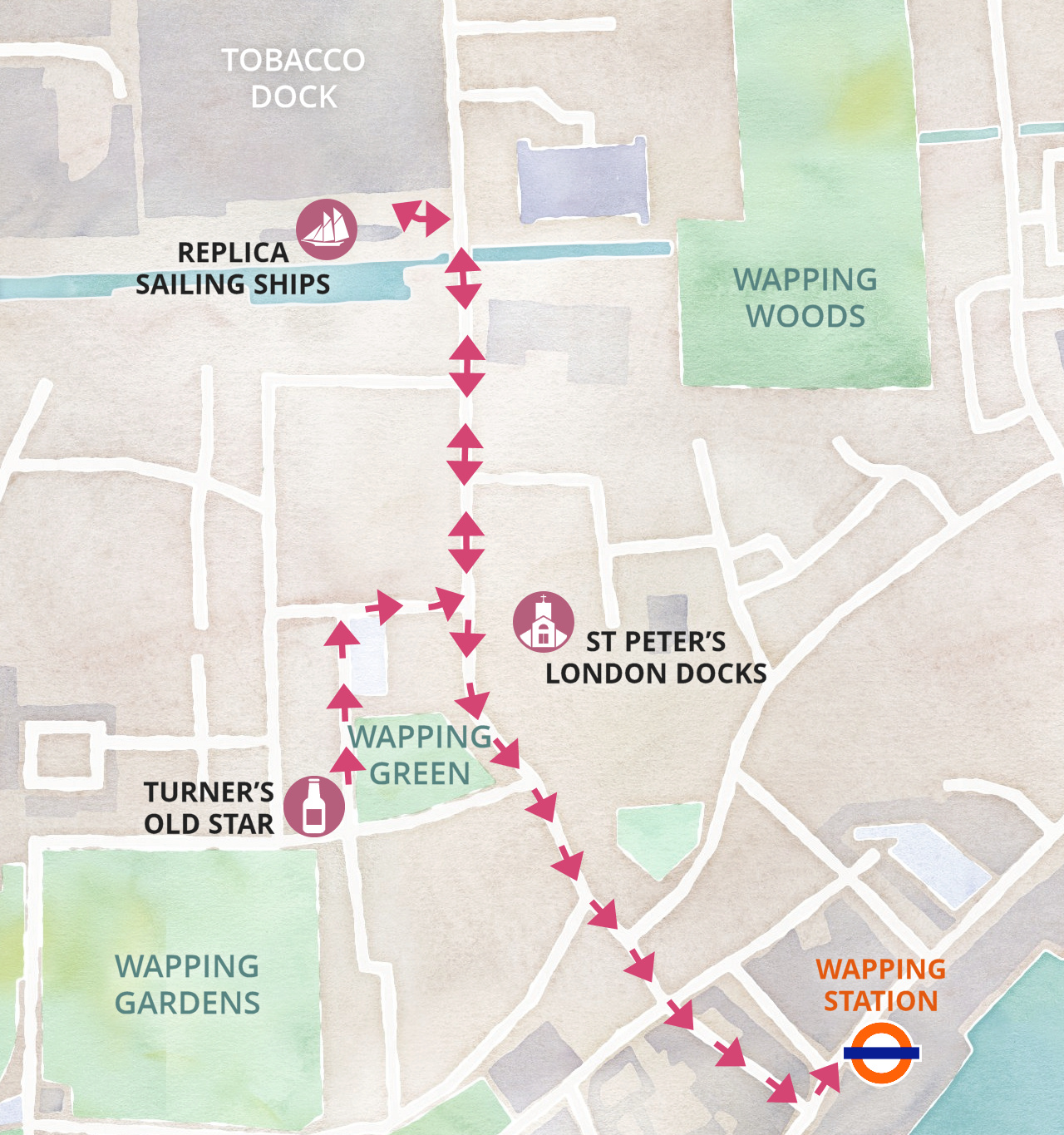

Finish: Wapping station |

From Tobacco Dock you now need to turn around and walk back down Wapping Lane to the very bottom, then turn left and 200 yards along on the right-hand side you’ll see Wapping station.

GETTING BACK TO CENTRAL LONDON

Wapping station is on the London Overground network (although it is underground at this point).

- To connect with the DLR service to Bank and Tower Gateway take the train from Platform 1 for one stop north to Shadwell, or

- To connect with the underground network then continue on one more stop to Whitechapel and change onto either the District or Hammersmith & City Line.

Trains from here will take you to many parts of central London.

Bus Route 100 will take you from Wapping station back into London. Stops include St Katharine Docks, Tower Gateway station, Bishopsgate, Moorgate station, London Wall/Museum of London, St Paul’s station.

Please note – there’s a separate walk that carries on from here to Limehouse and Canary Wharf.

If you like to continue further and do this walk now, then you’ll need to refer to the separate ‘Wapping to Canary Wharf walk’.