Updated: 13 July 2023 |

|

Length: About 2 miles |

|

Duration: 3 – 4 hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

A walk around Covent Garden

INTRODUCTION

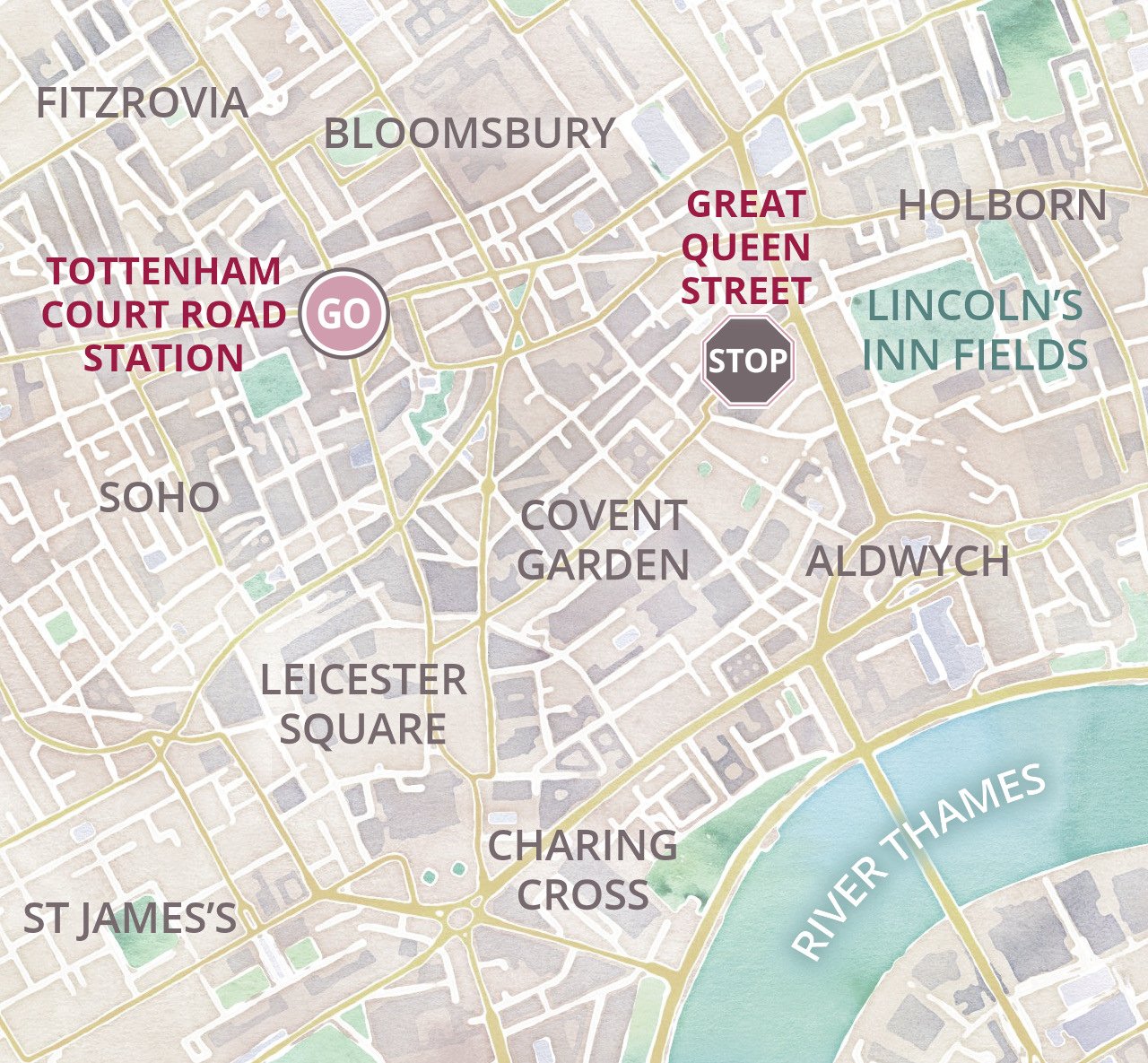

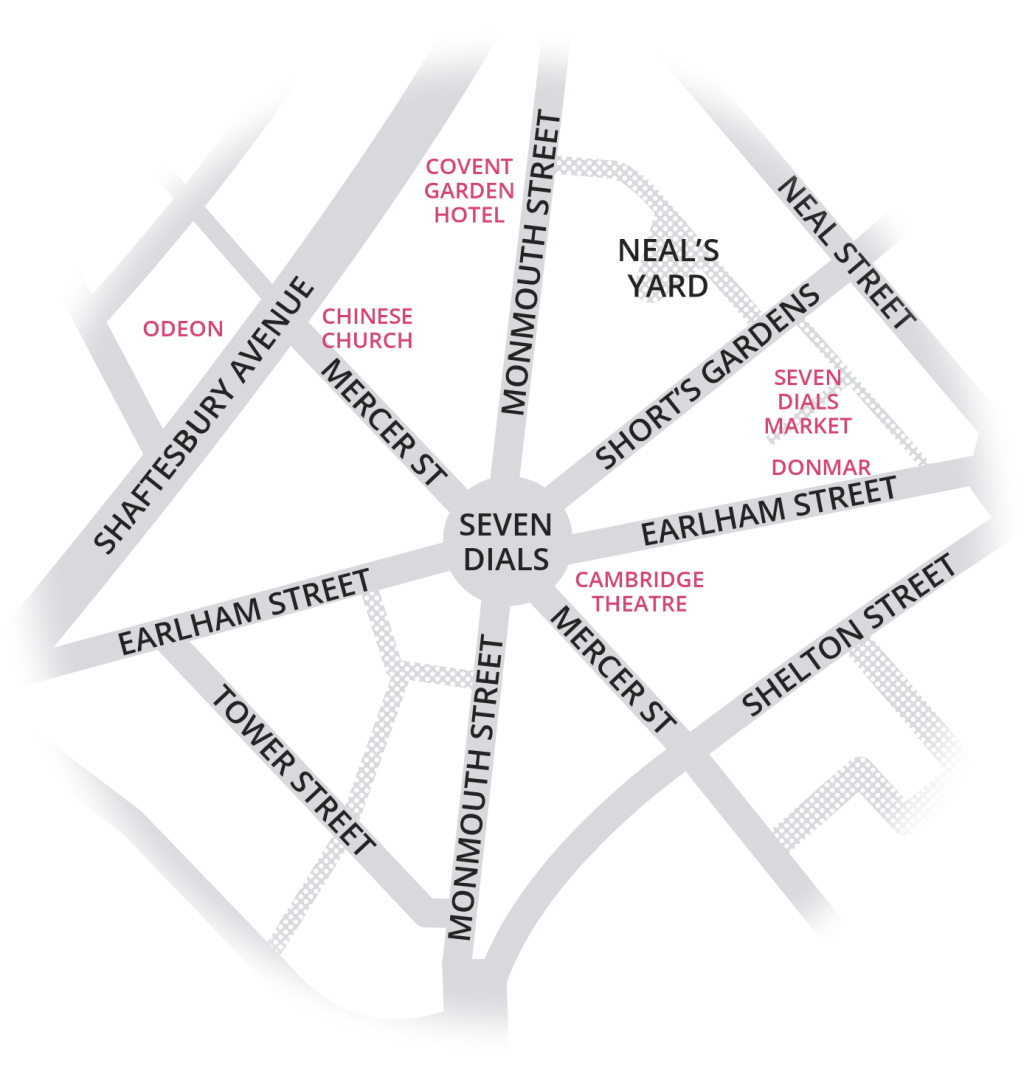

The area now popularly known as Covent Garden has expanded considerably over the years. Whilst many people now assume it includes much of the area between Tottenham Court Road station and Holborn station, and down as far as the Strand in the south, more specifically it could be said to lie between Long Acre to the north, St Martin’s Lane to the west, Drury Lane to the east and (probably) the Strand to the south.

However, with no ‘fixed boundary’, it’s debatable to say where it starts and finishes, and areas such as St Giles and Seven Dials are included in this walk.

As always, the duration of the walk will depend not only on your pace but also on how many sights you visit along the way (or pubs you pop into) and whether you follow any of my suggested diversions to view some of the buildings just off the recommended route. However, I reckon this walk needs at least three hours in order to do Covent Garden justice.

If you’re only interested in visiting Covent Garden Market, click here to jump to that section.

Start: Tottenham Court Road station |

|

Finish: Great Queen Street |

GETTING HERE

Tottenham Court Road station is served by the Northern and Central tube lines and the Elizabeth line. There are also many buses that will take you close to this location, including the 1, 8, 12, 14, 19, 22, 38, 55, 73, 88, 94, 98, 139, 159, 176 and 390.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF COVENT GARDEN

From being an orchard garden of Westminster Abbey to London’s first residential square to its wholesale fruit and vegetable market, and now one of the city’s most popular tourist, shopping and nightlife areas that attracts over 45 million visitors a year, Covent Garden has certainly had a remarkable history.

Recent archaeological investigations have shown that in the 7th century an Anglo-Saxon harbour and village were in existence at the southern edge of present-day Covent Garden. However, after the Viking invasion of Britain in the 9th century this disappeared, and the area was abandoned.

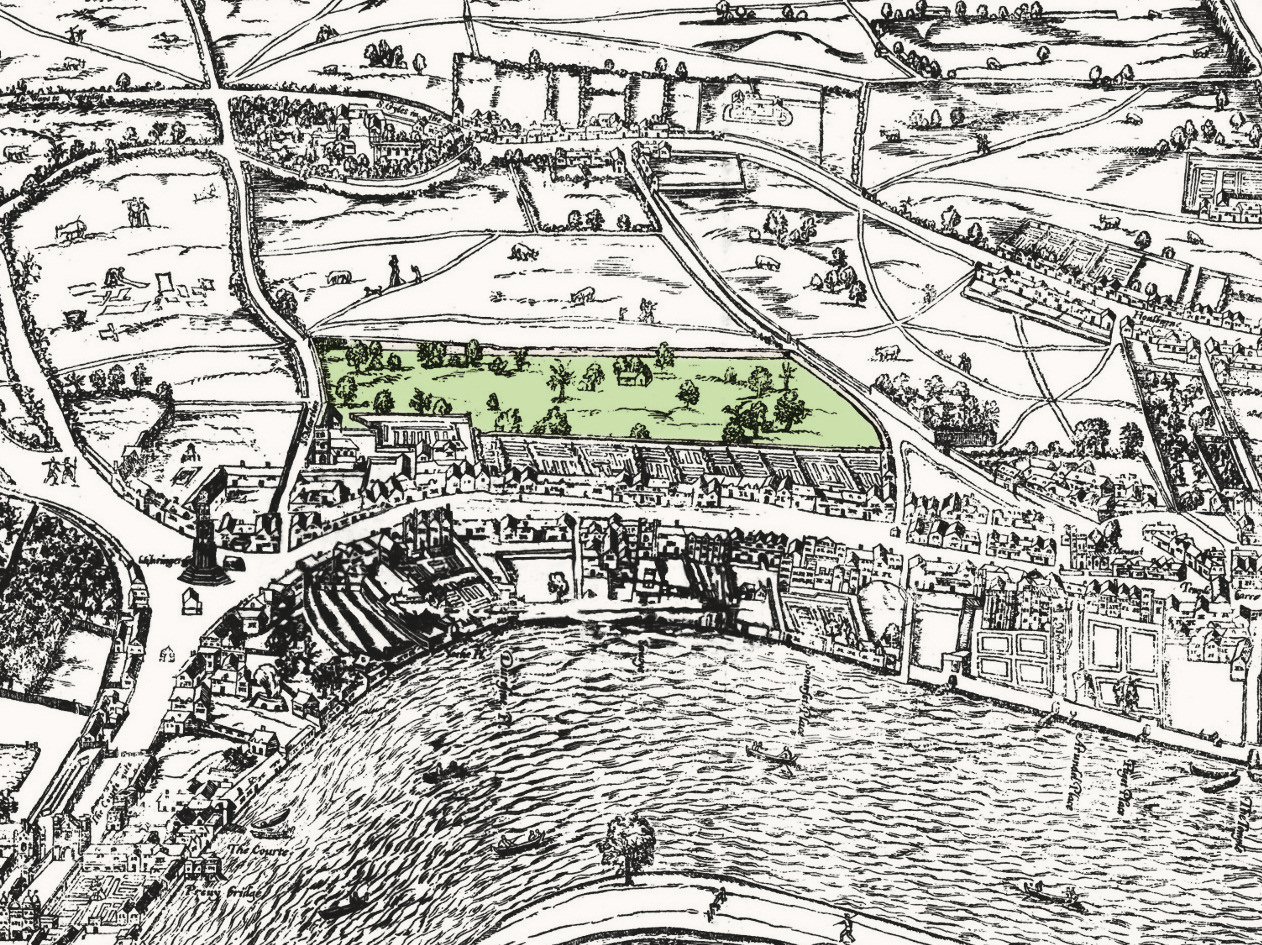

During the 13th century the fertile land here was claimed by the Abbot and Co[n]vent of St Peter’s Abbey – the forerunners of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey – as a garden to provide them with fruit and vegetables. This 40-acre plot is the reason for the area’s long-lasting name of ‘Covent Garden’. (In those days the word ‘convent’ hadn’t yet appeared in the English language. It was always ‘covent’ back then.)

See the garden on an old map …

Note that the trees in the garden are nowhere near being to scale. Real fruit trees would have been a fraction of the size that Agas drew them, as would the animals and people in the surrounding fields and lanes.

Show less

Then, fast forwarding to the 17th century, the 5th Duke of Bedford, whose father had been given the land and had built Bedford House as his home, employed the famous architect Inigo Jones to build what is widely accepted as London’s first ‘residential square’, setting the trend for numerous other squares in later years. The duke also granted permission for a few market stalls nearby, which over time saw it become London’s biggest fruit, vegetable and flower market.

STARTING THE WALK

The walk begins outside Tottenham Court Road tube station, on the corner of Charing Cross Road and New Oxford Street.

It’s a key central London junction, being at the crossroads of Oxford Street, Tottenham Court Road and Charing Cross Road and is served by numerous buses, whilst Tottenham Court Road station is served by the Elizabeth, Northern and Central lines.

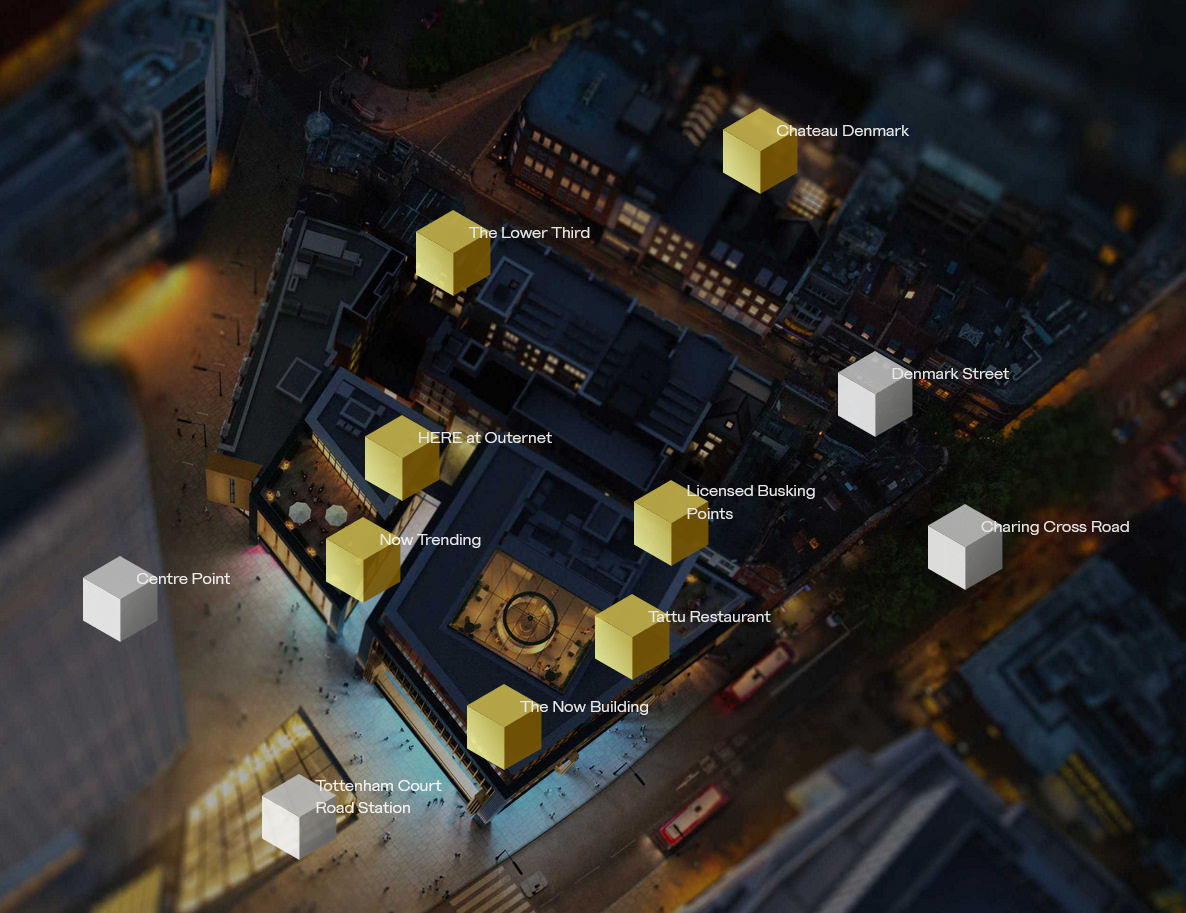

If you’ve arrived by tube at the station, then leave by Exit 4, signed ‘Charing Cross Road’. The escalator will take you precisely to the point where the walk begins, which is in front of the two large gold and black cube-like buildings, (which the walk will pass between).

If you haven’t arrived by tube, then head for the junction of Charing Cross Road and New Oxford Street. You’ll see the two glass ‘conservatory’ exits from the tube station – walk to the rear of them, and you’ll see the two large gold and black cube-like buildings.

We’re standing at the corner of an area that for hundreds of years had been called ‘St Giles’. It had gone from being one of the better class areas of London in the early 18th century to being one of the worst in the 19th and early 20th. This was once the site of one of London’s notorious gallows; it was also where condemned prisoners being taken from Newgate prison by cart to the gallows at Tyburn, near Marble Arch, would be allowed to stop and enjoy a last glass of ale in the Bowl Inn, which stood where Centre Point stands today, looming over you.

Centre Point, the enormous 34-storey office tower block, has been a London landmark since it was built 1966 and regarded as being one of London’s first skyscrapers. Previously offices, it was refurbished in 2016 and is now luxury apartments. (I recently saw a three-bedroomed apartment on sale here for over £7 million.) Though it is now Grade II listed, Centre Point was once described by the famous architectural critic Nikolaus Pevsner as “coarse in the extreme.”

We start by walking through the passageway between the two open fronted video display areas in front of you, with the Now Building on your right and Now Trending on your left.

They are part of the enormous ‘billion-pound’ new development called Outernet London, which is comprised of sixteen separate buildings, some new and some restored, extending back to Denmark Street, which we visit shortly.

The unmissable floor-to-ceiling high resolution LED screens – 23,000 square feet of them – are said to be the “largest deployment of video screens in the world.” These show constant film footage, ranging from spectacular nature scenes through to music videos. It’s apparently paid for by the promotional advertisements that appear at regular intervals, as well as hosting regular pop-up events.

Facing you at the end of the short passage is the entrance to the underground ‘HERE’ event space. This inconspicuous doorway gives no indication that it’s the entrance to a subterranean 2,000-capacity music & performance space (the largest new live events venue to be built in central London since the 1940s). This was a feat of engineering as it was excavated between the new Crossrail (Elizabeth) line and the buildings above.

Follow the short passage to the right, and then to the left (with yet more video screens), but as you do, notice the door on the right – the entrance to a rooftop restaurant called Tattu, which serves a Chinese-fusion menu, with Japanese and other influences. It is divided into a series of sections which appear to have rather obscure names, such as Dragon, Koi, etc. When I enquired about this, I was told they were all names of ‘powerful animals’. (No, I don’t know why either.) But there are certainly some stunning views from some of the tables that overlook the top of Charing Cross Road. The small bar also has an outside seating area.

Behind the new development, Outernet also includes Chateau Denmark, which has hotel rooms and apartments spread across 16 buildings in Denmark Place and Denmark Street.

The passageway leads you into Denmark Street, where we will be turning left … but first notice the line of guitar and other musical instrument shops facing you. One of the oldest is Rose Morris over on your right, which was established in the 1920s. And as you walk along to the left you can see several more. It is fascinating to look into the windows of these shops and see the range of highly valuable ‘vintage’ guitars – and their prices! On a recent visit I saw a 1961 Fender priced at £14,000 and a 1952 Gibson for £13,000.

The street’s long connection with music dates back to the 17th century. Then it was known for the printing of sheet ballads and some of the buildings still date back to around that time, particularly numbers 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10. Because of its large number of music shops the street became known from the 1920s as “Britain’s Tin Pan Alley”, after the Manhattan original.

Denmark Street: guitars for sale

In the early 1960s Denmark Street became the hub of London’s modern music scene, with shops selling both music and instruments. There were also recording studios, bars and hangouts that hosted musicians including Elton John, David Bowie, the Rolling Stones and later the Sex Pistols. Paul Simon, Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Wonder and Bob Marley all recorded here, and the Kinks even wrote a song about it. At one point, there were 12 live music venues within a five-minute walk of Tottenham Court Road, but thanks to rising commercial rents and the gentrification of the area by 2017 only one remained. Actually, the process was speeded up by the building of Crossrail (the Elizabeth line), which resulted in much demolition and redevelopment.

When the plans for the massive redevelopment of Denmark Street were announced, there were protests from people who feared many of the buildings were going to be demolished. However, now the redevelopment has taken place, it is clear that those worst fears were not realised and some of those original shops selling guitars and other instruments are still very much here.

Turn left along Denmark Street, where you pass Hanks, which proudly advertise that they are ‘London’s most famous guitar shop’, though I notice it didn’t actually open until some sixty years or so after Rose Morris.

(There is an excellent article about Denmark Street’s connection with music on the Guitar.com website.)

Continue straight ahead along Denmark Street and at the end you’ll notice the complex of enormous colourful office and apartment buildings that have finally removed any last traces of the old St Giles, beyond the church that gave the district its name.

Walk past the front of the Church of St Giles-in-the-Fields and take the second gated entrance down its left side. The path leads you around the back of the church and through the gardens – it’s quite a peaceful little area – then leave through the gate at the far end and walk down the short St Giles Passage.

Whilst the area is no longer known as St Giles (as you’ve already seen, nearly all of the older buildings have now been demolished and replaced), it was once a wealthy suburb, outside of the jurisdiction of the City of London. In 1668, after the Great Fire of London had devastated so much of the old city, tens of thousands of people moved out, with many settling in St Giles. Later there was another influx of people leaving the countryside to seek work in London. These had few skills and little if any money. Then soon after, many hungry and poor immigrants arrived, particularly after the potato famine in Ireland. Again, few had either money or the skills appropriate for living in a city. (The situation was the same in the adjacent Seven Dials area, which I cover shortly.)

The result was a rapid rise in enormous social problems, particularly overcrowding and crime. A survey of the parish in 1849 revealed that the population had risen to almost 40,000 and in many of the crumbling and dilapidated houses there were between fifty and ninety people sleeping each night.

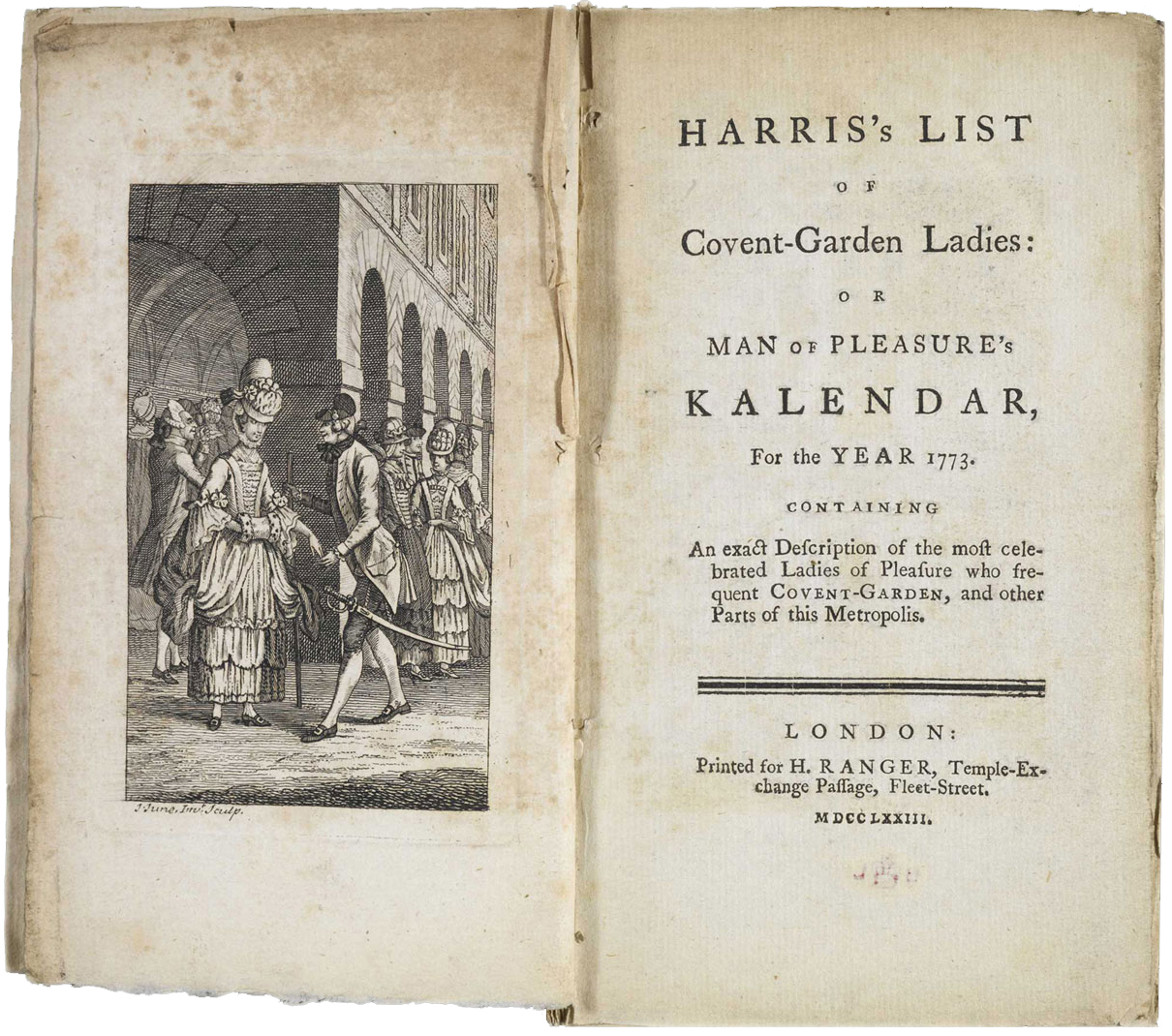

By the mid-19th century, the parish of St Giles had rapidly declined from once being described as “a most wealthy and populous parish”, into one of London’s worst and most notorious slum areas. It was a den of depravity, crime, vice and prostitution with countless brothels, with some having beds for up to 200 prostitutes. It was soon known as a ‘rookery’, which I say more about here:

On your right is the Phoenix Garden, an attractive community-run haven of greenery that’s open to the public during the day. Cross over New Compton Street and after just a few yards you reach Shaftesbury Avenue.

Cross over Shaftesbury Avenue into Mercer Street, alongside the Chinese Church. It was built in 1888 as a ‘Strict Baptist’ church and, after a confusing history, it became the Soho outreach centre of the Chinese Church in London in 2004. Services are held here every Sunday in Cantonese, Mandarin and English.

If you look back across Shaftesbury Avenue you can see the unusual frieze that runs along the front of the Odeon cinema, which opened in 1931 as the Saville Theatre – the last ‘live’ theatre to open in Shaftesbury Avenue. It is built in a distinctive art deco design, complete with the distinctive 125-ft frieze depicting ‘Drama through the Ages’. There are representations of ‘St Joan’, an ‘Imperial Roman Triumphal Procession’, ‘Harlequinade’, ‘War Plays’, etc. Prior to their installation, sections of the frieze were displayed at the Royal Academy in 1930. Along the top of the façade are a series of plaques representing ‘Art through the Ages’ which, as with the frieze, were sculpted by Gilbert Bayes.

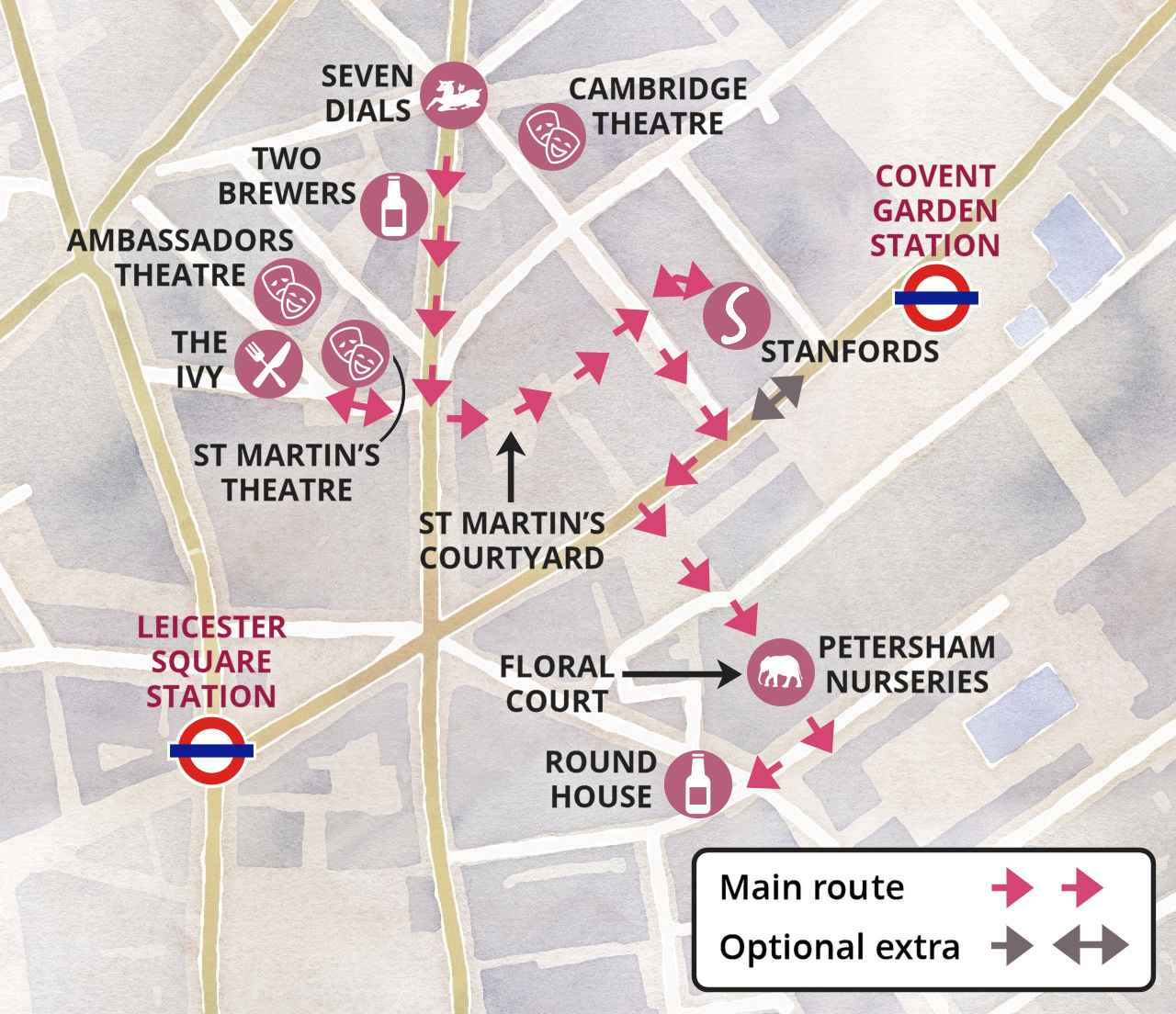

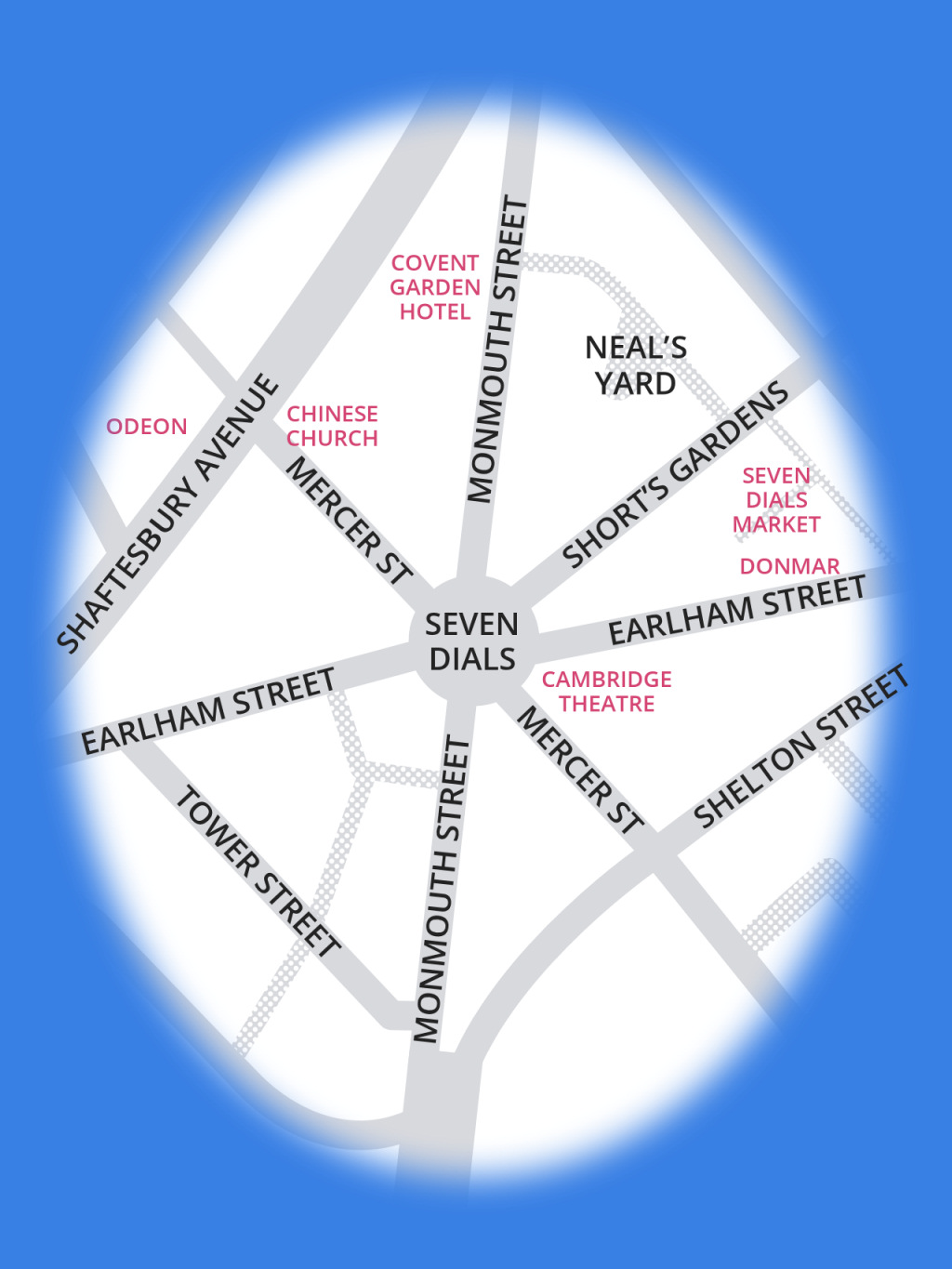

Walk up Mercer Street, which was previously called Little White Lion Street (most streets in the area have had their names changed over the years). And when you reach the top, you are at the centre of Seven Dials.

Seven Dials began its existence as an upmarket locality but it descended to the lowest imaginable depths before its modern renaissance as a trendy shopping, dining and entertainment zone.

Charles Dickens was drawn to the area when it was “infamous for its slums, crime and numerous accompanying evils.” He wrote about it in his essays called Sketches by Boz:

“The stranger who finds himself in Seven Dials for the first time … at the entrance to seven obscure passages, uncertain which to take, will see enough around him to keep his curiosity awake for no inconsiderable time.

“The peculiar character of these streets, and the close resemblance each one bears to its neighbour, by no means tends to decrease the bewilderment in which the unexperienced wayfarer through ‘the Dials’ finds himself involved. He traverses streets of dirty, straggling houses, with now and then an unexpected court composed of buildings as ill-proportioned and deformed as the half-naked children that wallow in the kennels.

“Here and there, a little dark chandler’s shop, with a cracked bell hung up behind the door to announce the entrance of a customer, or betray the presence of some young gentleman in whom a passion for shop tills has developed itself at an early age: others … brokers’ shops, which would seem to have been established by humane individuals, as refuges for destitute bugs, interspersed with announcements of day-schools, penny theatres, petition-writers, mangles, and music for balls or routs, complete the ‘still life’ of the subject; and dirty men, filthy women, squalid children, fluttering shuttlecocks, noisy battledores, reeking pipes, bad fruit, more than doubtful oysters, attenuated cats, depressed dogs, and anatomical fowls, are its cheerful accompaniments.”

“The stranger who finds himself in Seven Dials for the first time … at the entrance to seven obscure passages, uncertain which to take, will see enough around him to keep his curiosity awake for no inconsiderable time.

“The peculiar character of these streets, and the close resemblance each one bears to its neighbour, by no means tends to decrease the bewilderment in which the unexperienced wayfarer through ‘the Dials’ finds himself involved. He traverses streets of dirty, straggling houses, with now and then an unexpected court composed of buildings as ill-proportioned and deformed as the half-naked children that wallow in the kennels.

“Here and there, a little dark chandler’s shop, with a cracked bell hung up behind the door to announce the entrance of a customer, or betray the presence of some young gentleman in whom a passion for shop tills has developed itself at an early age: others … brokers’ shops, which would seem to have been established by humane individuals, as refuges for destitute bugs, interspersed with announcements of day-schools, penny theatres, petition-writers, mangles, and music for balls or routs, complete the ‘still life’ of the subject; and dirty men, filthy women, squalid children, fluttering shuttlecocks, noisy battledores, reeking pipes, bad fruit, more than doubtful oysters, attenuated cats, depressed dogs, and anatomical fowls, are its cheerful accompaniments.”

Walter Thornbury wrote in his book Old and New London, which was published in 1873, that “the business carried on in Seven Dials seems to be of a very heterogeneous character. It is the great haunt of bird and bird-cage sellers, also of the sellers of rabbits, cats, dogs, etc.; and as most of the houses, being of an old fashion, have broad ledges of lead over the shop-windows, these are frequently found converted into miniature gardens, which help, in some degree, to counterbalance the squalor and misery that is too apparent in some of the courts and lanes hard by.”

When the poor inhabitants who’d been living in Seven Dials were eventually moved out, they left behind many empty and half-derelict buildings. This got worse after the Covent Garden market relocated south of the river in 1974 and, even as late as the early 1980s, it was not an area where people wanted to live. As a result, the council drew up plans to demolish much of the entire area, including the market buildings.

However, thanks to the amazing efforts of the Seven Dials Trust and the Covent Garden Community Association, both community-run organisations, and notably the ‘Queen of Covent Garden’, most of the original Georgian and Victorian buildings of the Seven Dials district are still intact, with many now Grade II listed. The same applies to the actual Covent Garden market area, which we reach later in the walk. As a result, and in just a very short time, the overall area has become one of London’s most popular tourist districts, for sightseeing, shopping and nightlife.

Turn left into Monmouth Street, alongside the Mercer Street Hotel, which is owned by the Radisson/Edwardian Group.

On the opposite corner is the Crown pub. There have been licensed premises on this site since the beginning of the 18th century. The present pub opened in 1833 and was described by Charles Dickens as being a “hot bed of villainy.”

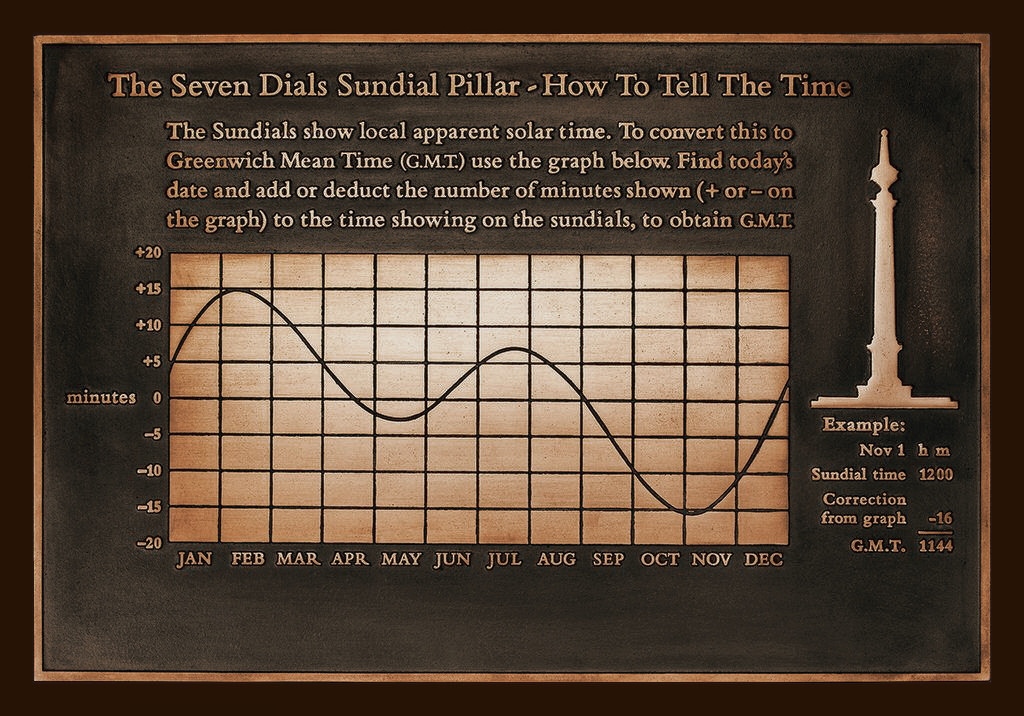

On the wall adjacent to the pub’s entrance is a small plaque that explains how the sundials on the top of the column in the centre of Seven Dials work. As it’s not that easy to read, I’ve reproduced it here, but in truth, having read it, I’m still not sure I could actually use the dials to tell the time. But I do love the message that’s been added at the bottom of the plaque, which says: ‘The happier the time, the quicker it passes’. And how true that is!

Halfway down the street is the five-star Covent Garden Hotel, but notice the inscription in the stone facia along its upper level, which reads, ‘Nouvel Hôpital et Dispensaire Français’. The hotel, which is owned by Kit and Tim Kemp as part of their Firmdale Hotels group, opened in 1996, though the building dates back to the 1890s when it was indeed a French Hospital. The hotel’s interior is beautiful, with a sweeping stone staircase, a wood-panelled drawing room and library, both with log burning fireplaces. It’s become popular with ‘celebrity’ guests, who have included Meryl Streep, Robert de Niro, Kate Winslet and Stephen Fry.

Directly opposite the hotel, notice the ‘sacking wrapped bale’ hanging from a hoist above a narrow passage. You see a number of these hoists on the older buildings around Covent Garden, harking back to when many of these buildings were warehouses and goods were hauled up and stored before being taken to the market.

As the sign says, this narrow passageway is the entrance to Neal’s Yard, (formerly called King’s Head Court), which we now walk through. It’s a colourful little place with small ‘rainbow painted’ shops and, perhaps not surprisingly considering its name, it’s where ‘Neal’s Yard’, the now famous organic and natural cosmetics company, opened back in 1981. It is said to have been Britain’s first certified natural and organic health and beauty company.

Neal’s Yard was also where the animation, editing and recording studios of Monty Python were between 1976 and 1987. It was owned by Michael Palin and Terry Gilliam, and apparently Michael lived here for a time – though that may be just rumour. And if you look up above the Neal’s Yard shop on the left you can see a blue plaque that reads – ‘Monty Python, Filmmaker, lived here’. Well, you wouldn’t expect anything else from them, would you?

What is hard to imagine is that years ago, this was another area that was once dangerous and avoided by any respectable citizen. In Jerry White’s book London in the 20th Century he tells of John Capstick, a newly recruited young policeman posted to Bow Street in Covent Garden around 1926, which I’ve put here:

Read John’s experience …

He ducked into the shadowy alley that led to the yard, and like mug I followed him. Too late I saw that one flickering gas lamp had been put out. Before I could draw my truncheon, I was on the ground, with four or five ruffians working me over with fist and boot. I staggered back to Bow Street police station minus helmet, whistle and truncheon. My face and body were covered with bruises, and I knew I was lucky to have escaped so lightly. But there was no sympathy in my sergeant’s eyes as he asked, “And what’s happened to you?”

I told him I’d been attacked by a gang of roughs. He asked me where, and I said Neal’s Yard, to which replied, “I thought so, that’s where they break all you young coppers in.”

Show less

Until the 1970s Neal’s Yard was just another run-down courtyard of buildings that the council planned to demolish and redevelop. It was saved by Nicholas Saunders, who was said to have been a “figurehead of London’s alternative scene.” (As an activist, Saunders wrote books teaching people how to enjoy London without lots of money – advocating for living in communities and emphasising spirituality.)

He purchased premises that were previously part of the Covent Garden Fruit and Vegetable Market, paying just £7,000. He wanted to live there, but the council wouldn’t allow it, so in 1976 he opened a wholefood store there instead, despite being told he couldn’t do that either. The business was hugely successful and presumably the authorities took no action as he went on to expand into a chain of eco-friendly businesses trading under the Neal’s Yard name – Neal’s Yard Coffee House, Neal’s Yard Bakery, etc.

He later approached Romy Fraser, a farmer turned entrepreneur and health advocate, and asked her to take over the Neal’s Yard shop, offering her a loan guarantee to do so. She did, and set up the Neal’s Yard Apothecary, later dropping the Apothecary name and changing it to ‘Remedies’. In 2005, wanting to move to Devon to set up her own sustainable farm, Romy Fraser sold the business to Peter Kindersley, the co-founder of publisher Dorling Kindersley. Despite receiving other proposals, she apparently opted for Kindersley’s offer – estimated at £10 million – because she thought he would keep the original spirit of the firm alive. The company has since grown into what is described as a ‘global leader’, with the USA now being its biggest market for sales. It still makes products at an ‘eco-factory’ in Dorset, as well as offering treatments such as massages and facials at some of its 40 or so outlets in Britain.

Keep to the left as you leave Neal’s Yard, passing the popular Barbary restaurant with its attractive horseshoe shaped bar, that’s popular for both drinks and its ‘Berber’ food.

We are going to cross over Short’s Gardens and into the Seven Dials Market building, but first notice the sign on the wall above the entrance which still says it was ‘Thomas Neal’s Warehouse’. This enormous 22,000 square foot building was a warehouse for storing bananas – whole pallet-loads were picked green, shipped over from Central America (and later the Canary Islands) and stacked floor to ceiling to be ripened under the steel-framed glass roof.

The first commercial refrigerated shipment of bananas had come to Britain around the turn of the 20th century and for many it was the first time they’d ever seen such exotic fruit. Until then, most people only ate fruit that was grown in the UK, such as apples and pears. Many other buildings around Covent Garden were once used to store fruit before it was moved to the nearby market for sale.

The building has had several other uses since, but more recently was converted into the huge and very popular indoor food court that you see today.

As you enter there’s a line of fast-food booths on the left – but turn right into the open-plan area and walk around. All around you are various food stalls whilst below is a huge eating area.

We leave by the rear entrance on the left and turn right into Earlham Street, but if you look to your left, then a little further down you’ll see the Donmar Warehouse.

Described as a ‘theatrical gem’, the Donmar was once part of the former banana warehouse and later a brewery. In the early 1960s it was used as a rehearsal space, after which it became a studio theatre for the Royal Shakespeare Company. After they moved out it was taken over as a fringe theatre venue by Donald Albury and Margot Fonteyn (the name derives from an amalgamation of their Christian names). This tiny theatre is run as a not-for-profit company and has a capacity of just 251 seats but is laid out so nobody in the audience is less than four rows away from the action. It offers an exciting range of productions, including many limited run and experimental plays. The Donmar has received 43 Olivier Awards since 1992 and often attracts big names.

On your left at the top of the street is the 1,231-seat Cambridge Theatre. It opened here in 1930 – which by West End theatre standards is quite recent.

You are now back in the centre of Seven Dials, with the Crown pub on your right, which we saw earlier.

From the top of Earlham Street walk across the centre of Seven Dials and take the second left into the attractive southern section of Monmouth Street, which has more small boutiques and shops.

Like all the streets in Covent Garden, it’s very different now from what it had been in the past. In his ‘Meditations on Monmouth Street’, Charles Dickens describes it as being “given over mainly to the sale of second-hand clothes.”

In 1873 Walter Thornbury described it as being “devoted chiefly to the sale of old clothes, second-hand boots and shoes, etc.; ginger-beer, green-grocery, and theatrical stores. Cheap picture-frame makers also abound here.”

Halfway down on the right is the Two Brewers pub. Prior to 1935 it was known as the Sheep’s Head Tavern – it even had the severed head of a sheep hanging outside. It has long been popular with theatrical folk, and there are many autographed photographs adorning its walls.

Along the Georgian terrace on the other side of the road, look up to the top of No.67 where a restored painted sign explains what previously went on here. It says: ‘B. Flegg, Estd. 1847 – Saddler & Harness Maker. Large stock of secondhand saddlery & harness, horse clothing’.

On the right at the bottom of Monmouth Street is an attractive-looking branch of the Rossopomodoro chain of Neapolitan restaurants, which I can recommend for excellent pasta and very friendly service.

Ahead is a monstrous modern 16-storey white and glass office block called Orion House. (I sometimes wonder how they get planning permission for such inappropriate development in an area like this.)

It was once the site of Aldridge’s Horse Bazaar and Repository for Horses and Carriages, described in 1895 as “especially famous for the sale of middleclass and tradesmen’s horses.” The last horse sale was held here in 1926, after which it was mainly used for the sale of greyhound dogs, and then from 1907 onwards, motor cars. It closed in 1940 and the buildings were demolished in the late 1950s, following which an office block called Thorn House was built on the site. This was remodelled in 1988–90 as the awful Orion House we see today.

Cross Tower Street and turn right alongside Orion House into West Street, with the offices of Equity, the Actors’ Union, on the corner. Facing you after a few yards is the world-famous Ivy restaurant. Nowadays there are dozens of Ivies but this is the original. It was a favourite in the past of major theatrical figures Noël Coward and John Gielgud, and is still popular today with celebrities, as well as others with equal amounts of money to spend. (Whenever I have passed in the evening there are numerous paparazzi outside waiting to photograph whichever celebrities happen to be dining there.)

When Abel Giandolini and Mario Gallati opened a simple café here in 1917, they could have never dreamt it would one day be one of the world’s most famous restaurants. Because of its location, their friendly service and long opening hours, it quickly became popular with the West End theatre community. For those who may be interested in reading more about the history of this famous restaurant, I have included a more detailed description in the appendix.

On your right is the St Martin’s Theatre. This is where Agatha Christie’s The Mousetrap has been playing now for 70 years – the longest-running play in the world.

The play started out in November 1952 in the Ambassadors Theatre, which is just a few yards further up on the same side, before moving to St Martin’s in 1974. Both theatres were designed by the same architect, and both are relatively small by West End standards, with the Ambassadors seating 453 and St Martins 550.

Turn around, cross over Upper St Martin’s Lane and walk up the passageway directly opposite leading to The Yards – there’s a sign above the entrance saying … ‘The Yards’. (It’s next door to the Dishoom Restaurant, where, as with the others in the chain, there always seems to be a queue outside.)

You are now in Slingsby Place, in a new development called St Martin’s Courtyard, with several bars and restaurants on the ground floor of the buildings. Continue under the arch – the sign says ‘To Mercer Walk’ – cross over Mercer Street (where we will shortly turn right) but first carry on ahead for another few yards up Mercer Walk to take a look at the world-famous Stanfords Map and Travel Bookstore, which was established in Covent Garden by Edward Stanford in 1853.

Notice the attractive ‘aluminium tree’ on the wall ahead. It’s by far the largest of a number of works around Mercer Walk by the sculptor Jill Watson.

Stanfords is just on your right around the corner. It’s a wonderful British institution; a shop that not only offers what is said to be the world’s largest collection of travel books, maps and other related products, but also serves coffee and light snacks. In the past Stanfords has supplied cartography for the British Army as well as for James Bond films. In 2019, Stanfords moved from the original premises around the corner in Long Acre, where they’d been since 1873.

Past customers at Stanfords have included Florence Nightingale, Captain Scott and Ernest Shackleton and more recently Kate Adie, Griff Rhys Jones and Bill Bryson. And it was to Stanfords that prime minister Neville Chamberlain turned to in 1939 in order to have maps produced highlighting the growing concern of Hitler’s Germany.

And more recently, it was from Stanfords that former Monty Python star Michael Palin set off on his 1988 tour to travel Around the World in 80 Days, which launched his travel writing career.

Next door to Stanfords is the Pineapple dance shop, whilst their studios are facing you across the road. Pineapple Studios are said to be the world’s premier dance studios and where the likes of Madonna and Beyoncé have rehearsed.

Walk back from Stanfords and turn left into Mercer Street. On your right, pass two interesting brick buildings, Tonbridge House and Maidstone House, whilst on the left is Jebson House. They were built as artisans’ dwellings in 1909 by the Mercers’ Company and whilst they may not particularly look it, they are now very desirable (and expensive) apartments.

At the end of Mercer Street, look up to the top of the building on the corner on your left and you’ll see a hand-painted sign saying, ‘Connaught Coachwork’ and ‘Armstrong Siddeley – London Agents’. There were once a number of workshops and sale rooms associated with carriages around here, including at least eight premises marked on old Ordnance Survey maps as ‘coach manufactories’.

The walk takes us to the right along Long Acre, but first you may want to walk to the left for 100 yards or so to see some of the early buildings that are still standing, many of which have fascinating architectural detail. There’s a lovely Italianate building, dating from the 1870s, with a sign high up on the front saying ‘Carriage Manufactory’, and another well-restored building just three doors further up, called Avon House.

Long Acre takes its name from a field that had been a part of the Covent Garden district since the Middle Ages.

Just 40 yards or so past Mercer Street, and on the other side of the road, we turn left into Conduit Court, a narrow alleyway that’s easy to miss – it’s currently next to TK Maxx, though of course that could change.

At the end of the short Conduit Court corridor continue ahead into Floral Court. This has been redeveloped to accommodate the Petersham Nurseries restaurant and shop, with lots of flowers and shrubs. There’s also an almost life-size wooden statue of an elephant made by a collective of artists in Tamil Nadu, in southern India, from dried Lantana camara, an invasive species of weed which chokes their forest habitat.

In their café/bistro they offer an afternoon ‘Elephant Family Tea’, which draws on Indian flavours and delicacies. It’s priced at £55 per person, with £10 going to the charity.

Turn right into King Street. As you exit you can see one of the famous ‘gas lamps’. And if you look up above the exit of Floral Court, then you can see a blue plaque explaining that this was where the theatre music composer Thomas Arne lived. He was born in 1710 and died in 1778. He was best known for composing the music for ‘Rule Britannia’. He was buried in the nearby St Paul’s Church.

(And if you look to the left, you can see the Covent Garden market buildings, which we will be reaching soon.)

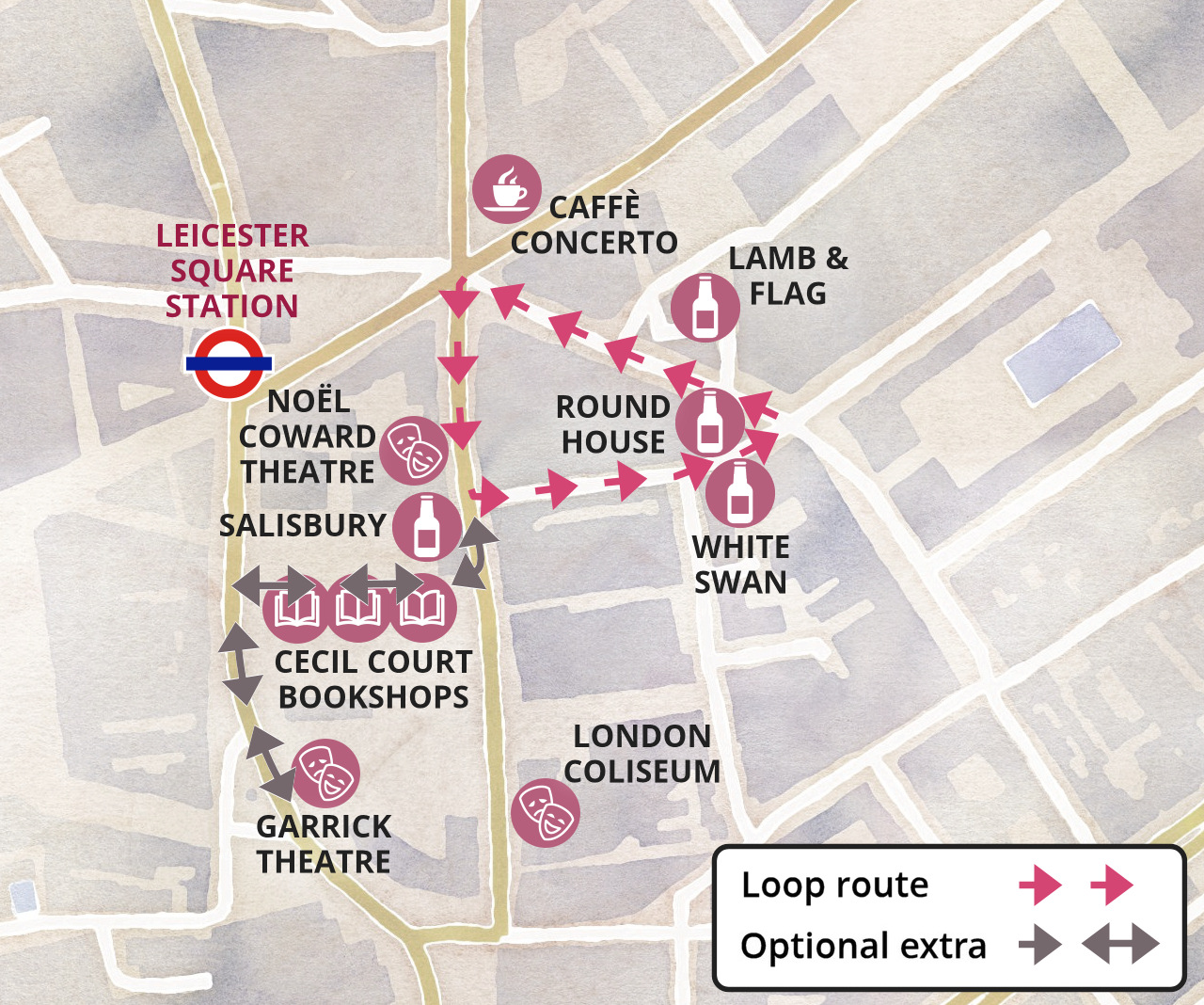

At the end of King Street turn right into Garrick Street – though I will mention here that if you’re getting tired or running out of time, you can miss out the next few minutes of the walk as we do a ‘loop’, returning here shortly, but from a different direction. But I would suggest you keep going if at all possible.

On the other side of the road is The Round House, which I explain more about later, at the end of the ‘loop’.

Optional ‘loop’ from the Round House

Turn right along Garrick Street, which opened in 1860 to improve access to Covent Garden market. Over 500 people were made homeless during the street’s construction – and, as was the case in those days, their houses were just demolished, and no compensation or help were offered to rehome them. The road was called New King Street at first and gained its present name following the arrival here of the Garrick Club (see below).

Just a few yards along you cross Rose Street; during the 18th century it was renowned for its squalor and the overcrowding of the dwellings that lined it. Debauchery of one kind or another was rampant, with prostitution, gambling, bare-knuckle boxing and cockfighting being just four of the ‘attractions’. If you look up the narrow street, you can see the frontage of the Lamb & Flag, a famous old pub where many of these activities took place.

It is one of the oldest and most interesting of the area’s pubs (and there are certainly plenty of them). Dating back to the 17th century, it underwent some restoration in the 1950s, but it is still essentially as it’s been for several hundred years, especially inside. It’s very compact, with just two small and usually crowded bars, and an old staircase that leads up to the well-preserved first floor. The pub is so popular and so cramped that even in the winter many customers have to enjoy their drinks outside, though now without the ‘attractions’ mentioned above.

Continue along Garrick Street. The somewhat dirty grey and severe looking building next on your left is the private members’ Garrick Club. The club was founded in 1831 and moved to its present, purpose-built home in 1864. There’s been considerable controversy lately as, despite today’s equality laws, it still doesn’t allow women to join. (There is no sign or name on the building – I guess they simply don’t need to!)

On the opposite side of the road, on the corner of Floral Street, is Le Garrick restaurant, which has been serving excellent French food since 1986. Having eaten there on several occasions I can thoroughly recommend it.

Cross Floral Street – where the original Stanfords Map and Travel Bookshop was until 2019, when it moved to Mercers Court. The ecclesiastical-looking building with a stone figure of Jesus Christ above the entrance on the corner of Floral Street was formerly a Mission House and school. Built in 1860, it is now Grade II listed and used as offices.

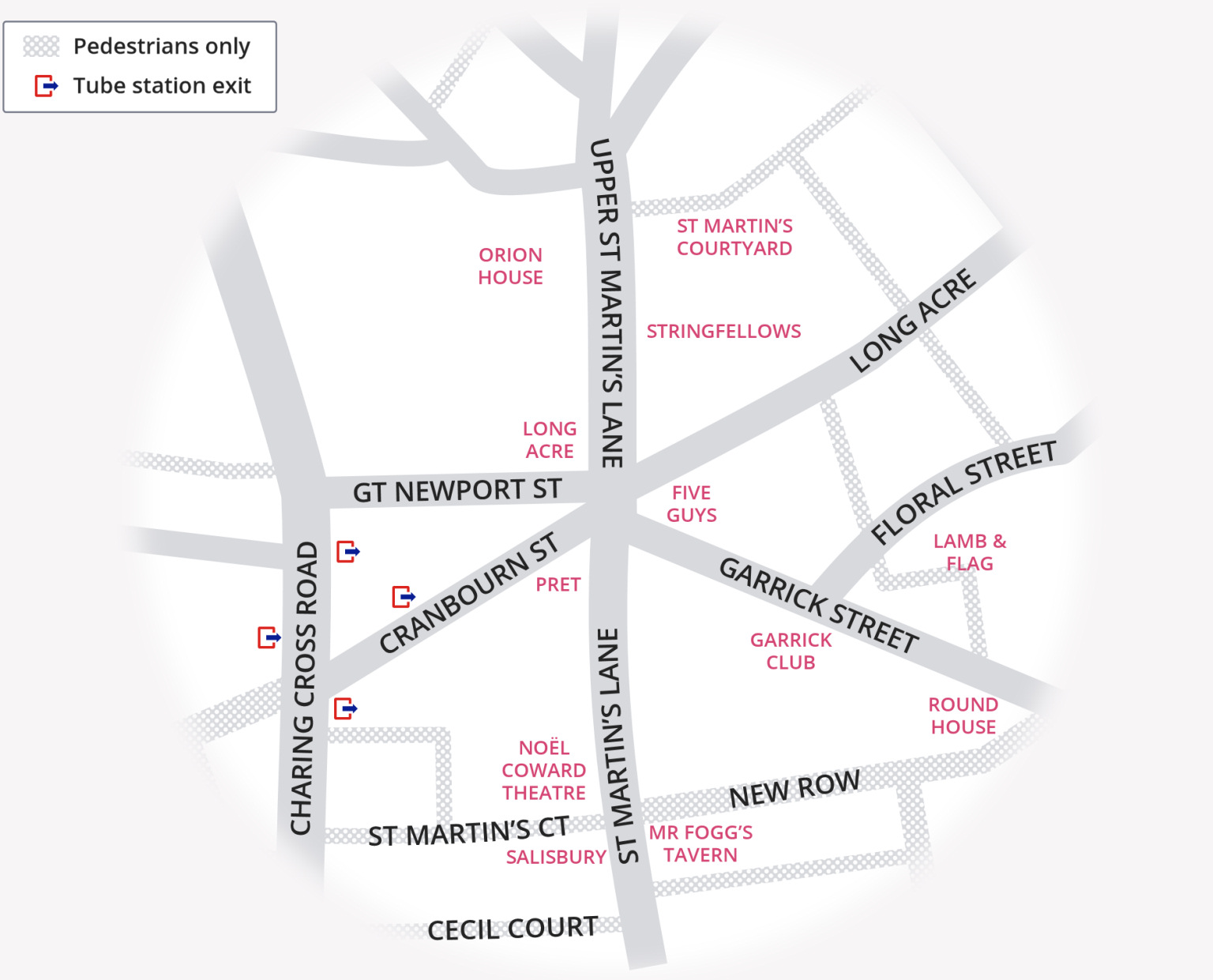

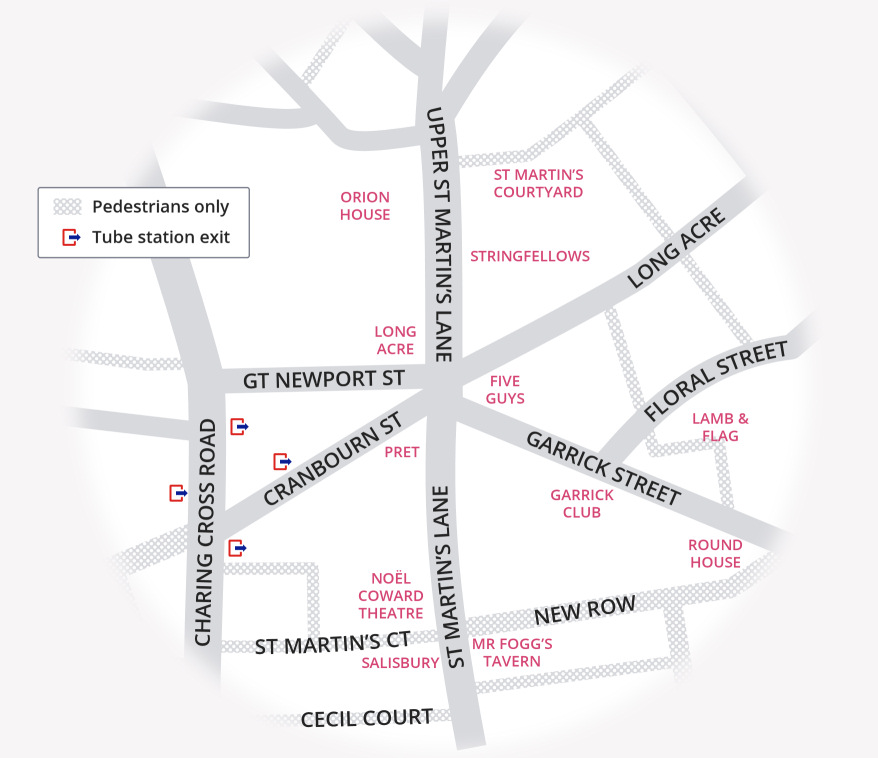

When you reach the end of Garrick Street you find a confusing (at least to pedestrians trying to cross) ‘staggered junction’, where several streets meet. On your right is Long Acre, where we were earlier, and going anti-clockwise the next street is Upper St Martin’s Lane. On the corner of those two streets is the excellent Caffè Concerto, which, besides having a café/bar on the ground floor, also serves excellent Italian meals on the first, where the large glass windows give good views of the surroundings. Almost next door to it in Upper St Martin’s Lane is Stringfellows, the world-famous ‘late night venue’ that opened here in 1980.

And for the more observant, if you notice a sign a little further up UpperSt St Martin’s Lane saying ‘The Yards’, then yes, this was where you were earlier. We do rather criss-cross and zig-zag on this walk!

The two streets opposite both lead to Charing Cross Road. However, the walk continues to the left, down St Martin’s Lane.

On your right you pass the Noël Coward Theatre, which opened in 1903 as the New Theatre.

On the next corner is the Salisbury, built around 1890 on the site of an earlier pub. It’s Grade II listed and in CAMRA’s (Campaign for Real Ale) National Inventory as an “historic pub interior of national importance.” They particularly mention the quality and opulence of the etched and polished glass and the hand-carved mahogany counters and woodwork. (The SS motif in some of the glass is as a result of it being originally called the ‘Salisbury Stores’. The use of the word ‘Stores’ was common with pubs of that time. It usually meant the establishment was also licensed for off-sales – and may have sold some groceries too.) It is also worth a mention that the Salisbury had been a ‘gay-friendly’ pub since the time of Oscar Wilde. The 1961 suspense film Victim – said to have been the first British film to include the word ‘homosexual’ – used the Salisbury as a shooting location.

If you look further ahead you can see in the distance the church spire of St Martin-in-the-Fields, as well as the amazing roof and globe of the London Coliseum. Although we don’t walk down that far, I will just mention a little more about the Coliseum which, when it opened in 1904, was one of London’s most luxurious and biggest theatres, with a seating capacity of almost 3,000. It’s still one of the biggest, with seating today for almost 2,400. It’s presently the home of English National Opera and also stages performances by English National Ballet, somewhat different from the theatre’s original aims, which was to be a place “not of highbrow entertainment.” Despite various restorations over the years, the theatre still retains many of its original features and is Grade l listed. And having been to several operas there myself in recent years, I can definitely recommend a visit if you get the opportunity.

I have written a little more about this fascinating theatre in the appendix.

Extension: Cecil Court |

The walk will continue to the left along New Row, (which is almost opposite the Noël Coward Theatre), but first, I would strongly recommend crossing over to the opposite (right-hand) side then after just another 20 yards or so turn right into the pedestrianised Cecil Court – particularly if you are interested in antique books, maps, prints and the like.

Cecil Court is a fascinating and peaceful street, dating back to the 17th century. It’s one of my favourite little streets in London, so I make no apology for the detail I give here.

Two things I particularly like – the first is the perfect symmetry of the architecture on both sides of the court, particularly the brickwork.

Second are the Victorian gas lights that still illuminate the street today. As you will appreciate if you visit after dark, they give a lovely soft, rich glow and help give Cecil Court its special ‘19th-century atmosphere’. On a dark winter’s evening, pull up the collar of your coat, listen to your footsteps clack on the flagstones and you can imagine yourself in a Charles Dickens novel. Or Sherlock Holmes or indeed any other of the many historical mysteries set in London in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It’s hardly surprising that it’s said to have been one of the inspirations for Diagon Alley in the Harry Potter books.

However, in 2022, Westminster Council decided to remove the Victorian gas lights and convert the lighting to LED. Tim Bryars, who owns a bookshop in Cecil Court, saw council workers digging a hole beside one of the lamps and when he asked what they were doing, they said ‘checking to see whether these old gas lamps could be converted to electricity’.

This forced Tim into action. Together with others keen to preserve these Victorian lamps, they formed the ‘London Gasketeers’ and began campaigning. And seemingly, at least for the moment, they appear to have won. (I say more about gas lamps in London when we reach the parish church of St Paul’s in Covent Garden.)

If anybody would like to visit the Garrick Theatre, then continue to the end of Cecil Court and turn left down Charing Cross Road.

Show more about the Garrick …

One of my personal favourite plays – J.B. Priestley’s An Inspector Calls – had an exceptionally long and successful run here in the 1990s.

Show less

Return to the Salisbury in St Martin’s Lane, cross over and head along New Row (formerly New Street), with Mr Fogg’s Tavern on the corner. It should perhaps now be renamed ‘Food Row’, as it seems to be one restaurant, café or bar after another. There are a couple of notable exceptions, such as a branch of Laird hatters and a Waterstones bookshop.

New Row’s food connections go back a long way: according to a book entitled Taverns in Town it was formerly nicknamed ‘Porridge Island’. The book goes on to say that “hereabouts were once the Bermudas, a maze of obscure little alleys, renowned for their unwholesomeness, and the name Porridge Island was on account of the great preponderance of inexpensive cook shops which used to line it.” The book adds that the whole area was cleared in the late 1820s “in the reforms that preceded the laying out of the nearby Trafalgar Square.”

Of particular interest is The White Swan pub; it’s a small and lovely old coaching inn that was mentioned by Samuel Pepys in his diaries. However, New Row is certainly no longer as described on a sign on the pub’s wall – “a street fizzing with character and intrigue.” Packed with tourists maybe, but certainly not character and intrigue anymore. Once owned by Hoare & Co, the famous London banking firm, (a large mirror inside still promotes ‘Hoare & Co’s Celebrated Imperial Stout & Sparkling Ales’). The pub was featured in Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey novel, Murder Must Advertise.

You are now at the top of New Row and you have completed the ‘loop’ and are back to the Round House.

If you skipped the ‘loop’, then this is where you should pick up the walk again.

Built soon after the creation of Garrick Street, the Round House was originally called Petter’s Hotel and was popular with both market workers and theatregoers.

In 1943, and clearly inspired by the shape of the building, the name was changed to the Round House. Since then, the pub has changed very little.

Turn right down Bedford Street, cross over and then after 20 yards turn left through the iron gates into Inigo Place (topped with the coat of arms of the Russell family who still own the land), which leads into the churchyard of the parish church of St Paul’s.

The church garden is surrounded on three sides by tall 18th century houses. I do find it interesting how the developers left the rear of the houses so plain yet with such attractive architectural features on their frontages – clearly a simple way to save money on building costs.

It is a delightful haven of peace amidst the bustle all around. Trees give shade and a number of benches allow you to sit and rest. These have been dedicated by the families or friends of the deceased, most of whom were associated with the theatre – St Paul’s is known as the Actors’ Church. It is interesting to read some of the inscriptions – Beryl Reid, John Thaw (of Morse fame), Carmen Silvera, (of ’Allo ’Allo!) and many more. There’s a rosebush in the garden dedicated to Bill Fraser (of Bootsie & Snudge fame, for those old enough to remember), with the lovely inscription ‘fell asleep’.

The garden is so well cared for, and on several occasions when I have visited, I’ve been fortunate enough to meet and chat to one of the hardworking ‘unofficial custodian gardeners’, a delightful lady who gives up a couple of days a week to care for the flowers and plants. And on a visit during the pandemic I met one of her younger colleagues, an actress who was volunteering while the West End theatres were closed. Her name is Kathryn Meisle, and she told me that one of her early stage appearances was playing Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady – delightfully appropriate as we were standing just a few yards from where Eliza first met Professor Henry Higgins.

What really add to the atmosphere of the garden are the original gas lamps, still in situ, despite Westminster Council’s plan to remove them and convert the lighting to LED, which I mentioned earlier. It’s only if you come here after dusk that you can appreciate the subtle light these lamps give. Gas lights glow with a soft parchment-coloured light; very different from the often bright and harsh white light generated by the more modern electric lamps.

If the church is open, then I do suggest that you take a look inside. Around the walls are plaques to so many familiar names. Some of the earliest well-known people to be buried here include the artist J.M.W. Turner and Sir William Gilbert, who wrote the libretti for the G&S operas. Indeed, the relationship with the acting profession goes back to when the church first opened, particularly as a result of its connection with the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, just a few hundred yards away. It was also the burial place of Margaret Ponteous, who is sometimes said to have been the first known victim of the 1665–6 outbreak of the plague in London (but Daniel Defoe wrote of earlier victims, and I’ll say more about that when we reach Drury Lane).

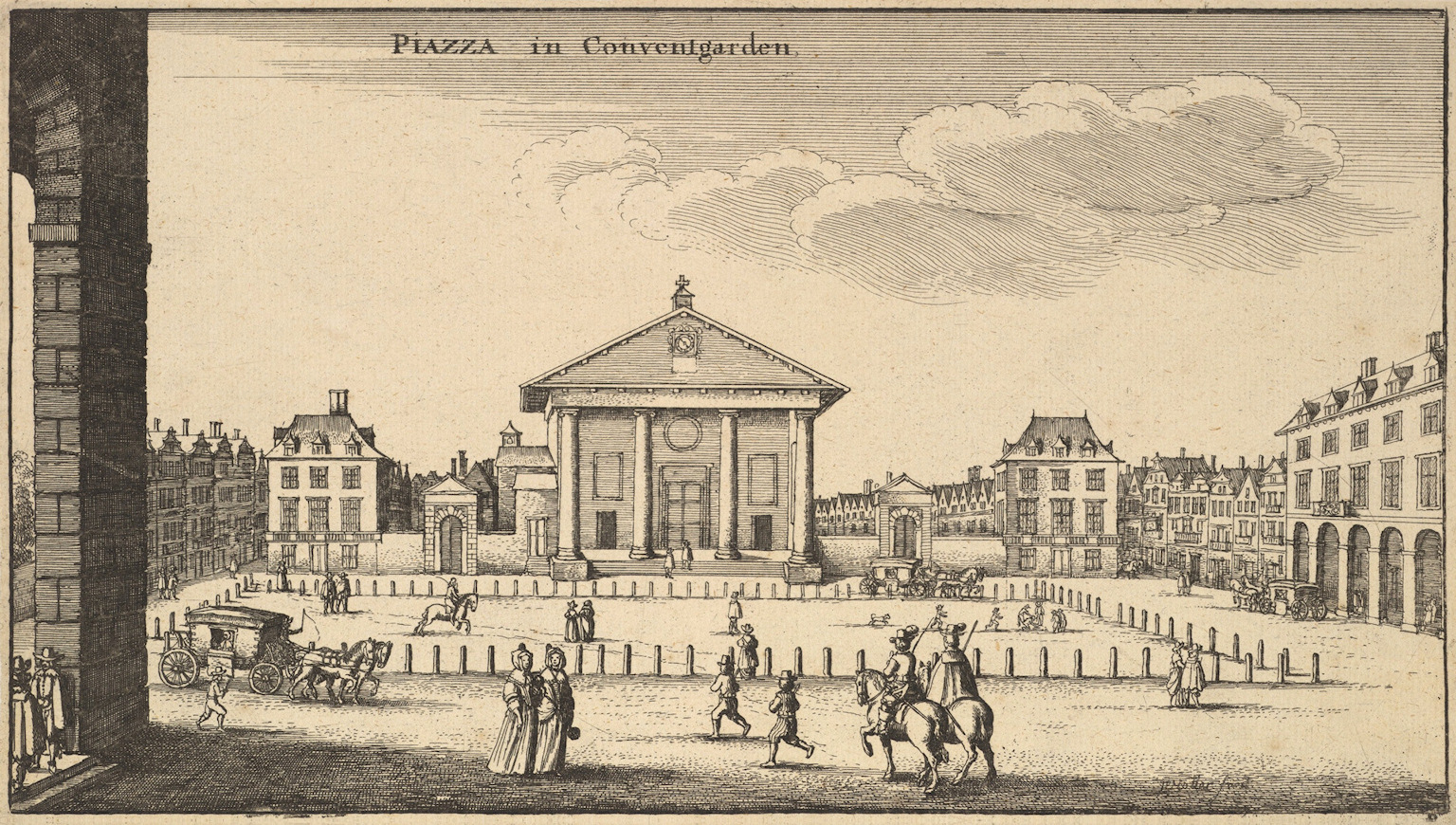

Incidentally, whilst you appear to enter the church through the rear, this is in fact the main entrance. This certainly wasn’t planned; the main entrance doors were meant to have been at the other end of the church, beneath the portico that face the Covent Garden square, as you will see shortly. But they never were. As this was the eastern side of the church, the Bishop of London insisted the altar must follow tradition and be placed against this east wall, so an entrance here was impossible. As a result, only the rear and side doors are used to access the church. However, despite this setback, the architect, Inigo Jones, stuck with his original plan for a neoclassical portico to front the piazza – and even included a false door.

Who was Inigo Jones? …

He was the son of a Smithfield clothworker and, according to Sir Christopher Wren, he had served an apprenticeship as a joiner near St Paul’s Cathedral. However, he quickly showed exceptional talents as an artist and a designer, and he travelled to Italy to study the works of their famous architects and builders. He became greatly enthused by the work of Andrea Palladio and upon his return to Britain began designing buildings in what became known as the Palladian style.

As the King’s Surveyor of Works he was responsible for the architecture of grand buildings in London such as the Banqueting House in Whitehall and the New Exchange in the Strand. Inigo was also a renowned for his ability as a theatrical set and costume designer.

His Covent Garden Piazza was the first regularly planned square in London, which then became a model for future developments in the city.

Piazza in Co[n]vent Garden by Wenceslaus Hollar, c.1647

Show less

Leave the church through the narrow archway to the right of the church’s entrance (as you face the church), pass the blue Tardis-styled booth (which is used for storing cleaning equipment but I don’t know whether that was always its purpose) and exit through the passage that leads into Henrietta Street – named after the wife of Charles II.

Turn right. You can now see how attractive the frontages of these buildings that back on to the churchyard are.

The film-maker Alfred Hitchcock lived at No.3 for a while and used Henrietta Street in his thriller Frenzy, which was about a Covent Garden fruit vendor who becomes a serial sex killer. Alfred must have known the market well, as his father had been a wholesale greengrocer there.

The novelist Jane Austen lodged in the street during one of her many visits to London. Her brother Henry was a banker, and lived above the offices of Austen, Maunde and Tilson’s at Number 10. Her verdict on Covent Garden at the time was: “an area all dirt and confusion, but in an interesting way.”

At No.25 a green plaque marks the site of Rawthmell’s Coffee House, where the social reformer and inventor William Shipley founded the Society of Arts (it later it became ‘Royal’) in 1754.

At the end of Henrietta Street, turn left back into Bedford Street.

After the Great Fire of London, a number of businesses moved out of the city, with some settling in Bedford Street. In 1720 historian and biographer John Strype wrote, “Bedford Street, a handsome broad street, with very good houses, which, since the Fire of London, are generally taken up by eminent tradesmen, as Mercers, Lacemen, Drapers, etc.”

In the late 19th century Bedford Street had become a centre for London publishing houses. Among others, it was home to the offices of Heinemann, JM Dent, Frederick Warne and Macmillan.

In 1875 the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh worked in an art dealer’s shop at No 25, though apparently his moody behaviour so upset the management that he was transferred back to Paris.

In 1860 a Jewish tailor had relocated his business from the East End to Bedford Street and decided to change his name from Moses Moses to Moses Moss. When he died in 1894, he left his business to Alfred and George, two of his five sons. It eventually became better known as ‘Moss Bros’. A gentleman went into their tailor’s shop one day asking if he could borrow a suit, as he couldn’t afford to have one made, and came back several times to ask the same thing … and the rest, as they say, is history. Moss Bros became a household name. Their success was such that the company eventually owned a number of properties along the street. (And as an update to this, the company was badly affected by the Covid pandemic but, having closed a number of less profitable stores, they have apparently bounced back as a result of moving into selling more casual clothes.)

And as we turn left in Maiden Lane, I will just mention that when I first started preparing this walk, the building on the left-hand corner of Bedford Street and Maiden Lane was the offices of the upmarket magazine The Lady. They had been here for well over 100 years but have recently moved out and the premises have been sold.

Take the next left into Maiden Lane.

Maiden Lane was once part of an ancient track that ran through the convent garden to St Martin’s Lane. The right-hand side was said to have been the old mud wall of the garden, which after 1610 was rebuilt in brick. Behind the wall were other gardens, with stables and haylofts. After building began here, around 1635, several alleys connected the lane to the Strand, and three are still left today. One is Exchange Court, which you see after you’ve turned left into Maiden Lane, and it runs down the side of the Porterhouse pub. The painter J.M.W. Turner lived in a house that was once on this site, where his father had worked as a barber and wigmaker.

The Porterhouse, which has an outdoor seating area in front, is a cavern-like place, with an industrial-styled interior of steel beams and exposed pipework. It’s on several levels (must be a nightmare for anyone who arranges to meet somebody here – you’d never find them). It’s owned by the Irish Porterhouse Brewery Company and sells an extensive range of its own beers and ales.

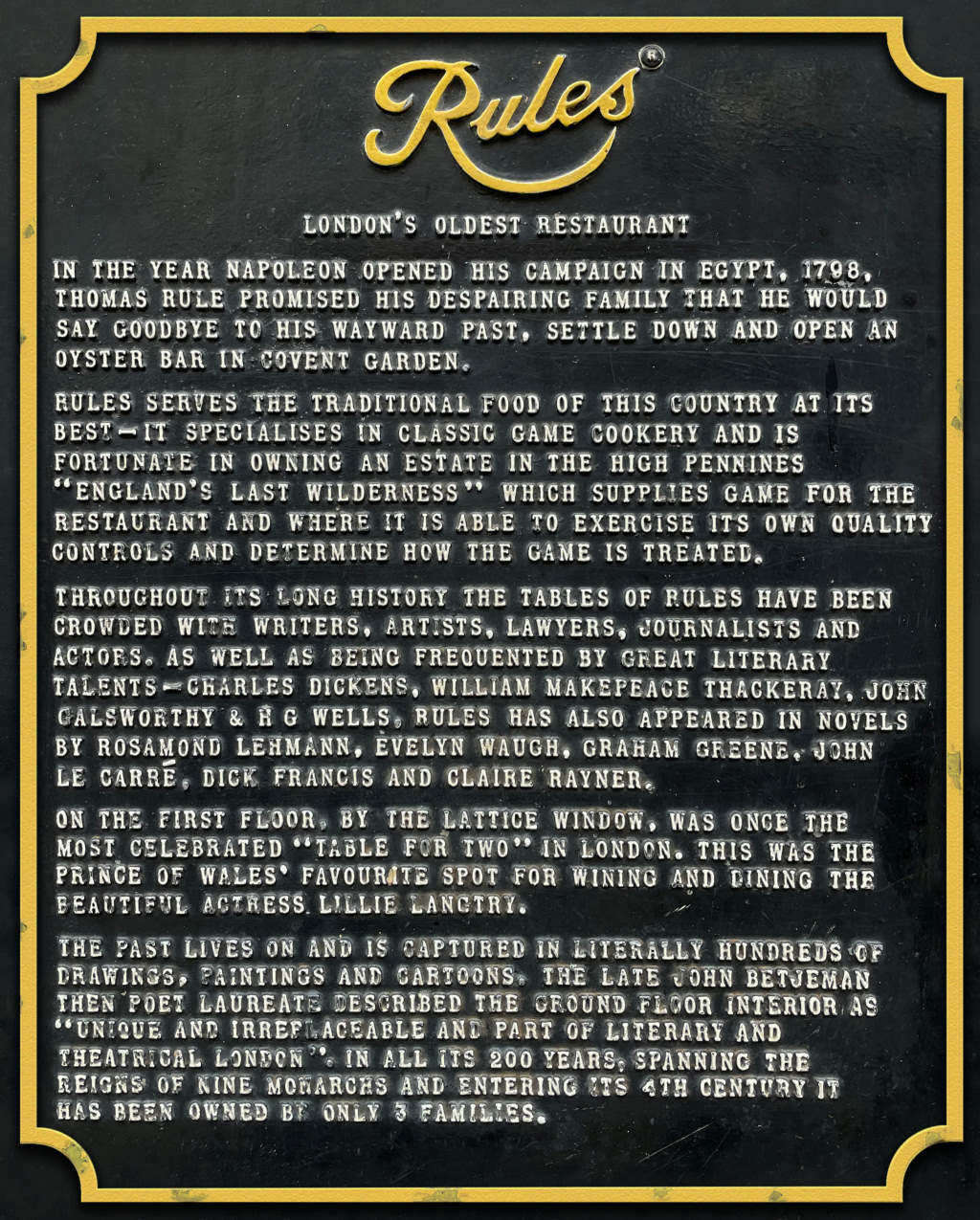

Next to it is one of two stage doors in the street of the Adelphi Theatre and a few yards further on the left is Rules, arguably London’s oldest and most famous restaurant. (Wiltons was founded earlier but it has moved around St James’s at least six times over the course of its existence whereas Rules has stayed put in Maiden Lane.)

The restaurant was opened in 1798 by Thomas Rule, initially (like Wiltons) as an oyster bar. It was rebuilt in 1873 and soon became a favourite of the future Edward VII. When he was Prince of Wales, he used to sit at the table by the latticed window on the first floor, entertaining his ‘girlfriend’ Lilly Langtry.

For many years it was popular with members of the theatrical profession. The list of famous actors who were regular visitors, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries reads like a ‘Who’s Who’ of the theatre and includes such figures as Henry Irving and Laurence Olivier. Indeed, still on the walls of the restaurant are portraits of many actors who have been past diners. (Having said that, I don’t think there are many 21st century actors visiting today – these days they are more likely to be seen in places such as the Ivy and other somewhat ‘trendier celebrity hangouts’).

Rules is still noted today for the quality of its food, which tends to be very traditionally English, offering oysters, pies and game. Indeed, not many restaurants today serve dishes that range from steak and kidney pie and roast crown of mallard to whole roast grouse. Apparently, they even have their own ‘game estate’ in the High Pennines – the restaurant is said to serve around 18,000 game birds a year.

Directly opposite, on the rear wall of the Vaudeville Theatre, a blue plaque explains that the French philosopher, satirist and playwright Voltaire lived here back in 1727. He had been exiled to England as an alternative to imprisonment in France and lived here for part of the time, as this enabled him to be close to his publisher. Voltaire mixed with other intellectuals and literary figures during this time and published several essays in the English language. He was allowed back into France after two-and-a-half years in exile.

Just a little further along, again on the right, is the Roman Catholic Corpus Christi Church. Its entrance is easy to miss and might not look particularly welcoming, but once down the steps and through the small wooden door you find the most beautifully ornate and decorated church.

At the end of Maiden Lane turn left into Southampton Street. Look to the right along Tavistock Street and you’ll see the terrace of the Prima Sapori d’Italia restaurant. As you’re now past the halfway point in the walk, I can thoroughly recommend it if you’re feeling hungry. It’s open all day and early evening. But stay on Southampton Street unless you’re making a diversion to eat at Prima.

On your left are two terraced houses dating from 1708, though both have undergone some alterations since then. Number 27, which we pass first, is particularly important (and Grade II* listed) because more of its original features have been preserved – and it was the residence of David Garrick, who you can read more about in the appendix. Having paid 500 guineas for the house, he and his new wife Eva Maria moved in soon after their marriage in 1749. It remained their city home for 23 years. The house doesn’t have a blue plaque (nobody gets two, and David’s is at Garrick Villa, his summer retreat by the Thames in Hampton) but above the doorway there’s a bronze memorial tablet that was commissioned by the Duke of Bedford in 1900 and designed by his personal architect Charles Fitzroy Doll.

In 1903 the ground floor of number 26 was converted into a shop, which is now Abuelo, an “Australian meets South American coffee-house and kitchen.”

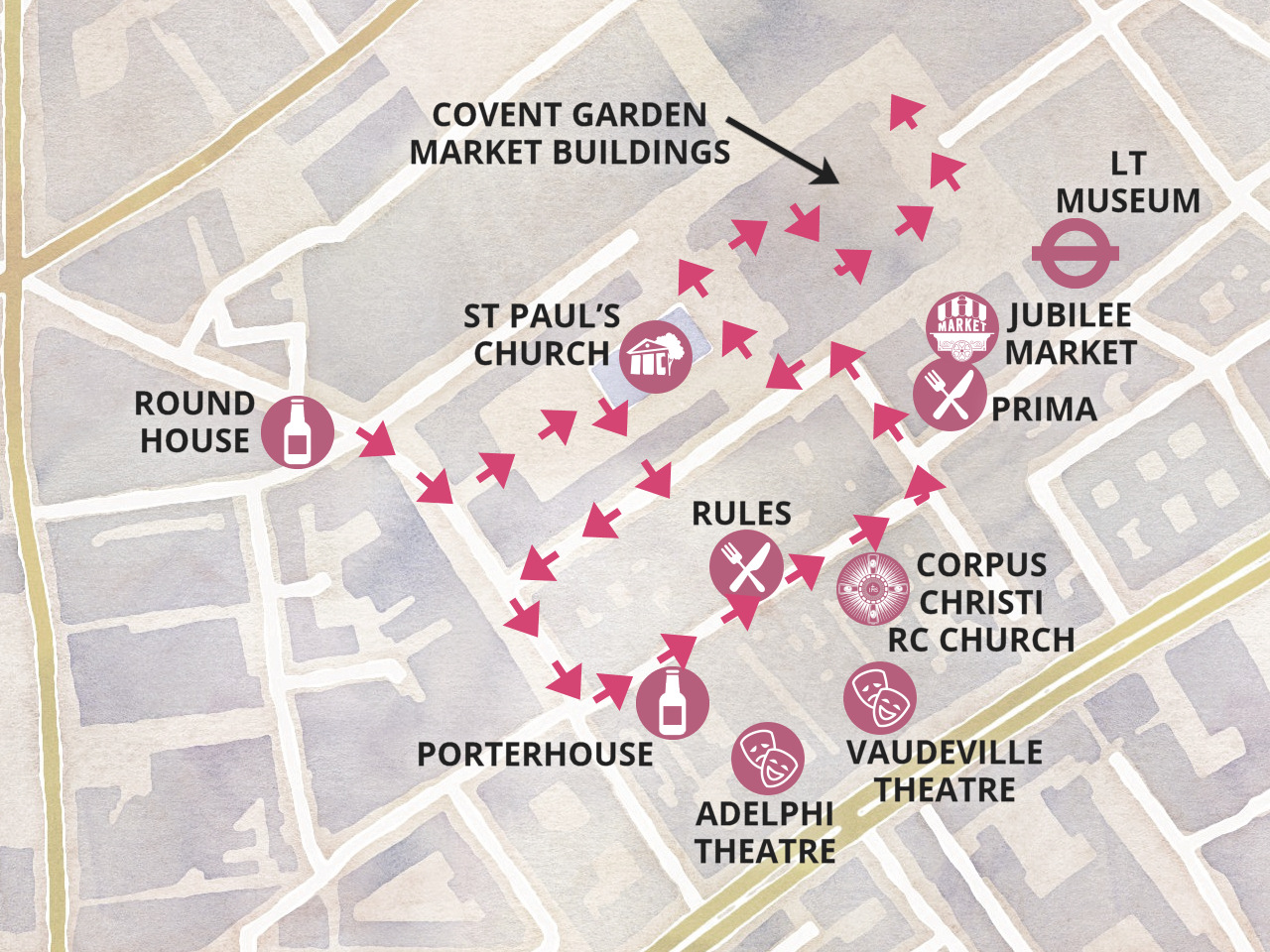

At the top of Southampton Street we at last arrive at the famous Covent Garden market piazza.

VISITING THE MARKET AREA

On the right at the top of Southampton Street is the Jubilee Market Hall, which opened in 1904 as the ‘Foreign Flower Market’ and was Grade II listed in 1980. Restoration began in late 1985. Offices and flats were built above the western section as part of a deal to save the whole of the market from redevelopment. During the excavations in 1985 the first Anglo-Saxon remains were found in Covent Garden. The Jubilee Market was opened by the Queen two years later.

On Mondays the Jubilee Market specialises in antiques and collectables; from Tuesday to Friday there’s a general market with a mixture of permanent and pop-up stalls selling everything from clothes and bags to posters and ‘knick-knacks’; on Saturday and Sunday there’s an emphasis on arts and crafts.

There is a plaque on the rear wall of the building put up in memory of the many thousands of donkeys that for centuries (and some as recently as 1970) were used to pull the carts of produce around the market.

From here I suggest you begin exploring by walking in a clockwise direction around the piazza to visit the central market buildings.

So, turn left out of Southampton Street and immediately turn right, passing on your left the front of St Paul’s Church, which you visited a few minutes ago.

The church has an impressive Tuscan portico over what was intended to be its entrance. However, as I’ve already explained, the church authorities insisted that the altar had to be at this – the eastern – end of the church, so the main entrance had to go on the other side.

It was under this portico that Professor Henry Higgins met Liza Doolittle, the Covent Garden flower seller, in George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play Pygmalion, which was later turned in to the 1964 musical My Fair Lady, starring Audrey Hepburn and Rex Harrison.

It was also in front of the church that on Friday 9 May 1662 the first known performance of a ‘Punch and Judy’ show took place. We know the date as it was watched – and recorded – by Samuel Pepys. In his diary he wrote: “Thence … into Covent Garden … to see an Italian puppet play that is within the rayles [rails] there, which is very pretty, the best that ever I saw …” He was so impressed that he brought his wife back to see another show two weeks later.

Read more about ‘Punch & Judy’ …

Charles Dickens was a fan and mentioned ‘Punch & Judy’ in The Old Curiosity Shop. Back then the performances were said to be far more aggressive and naughtier than they are today, and in the 1840s campaigners wrote to Charles Dickens, asking him to support their efforts to have the shows banned. Dickens replied, “In my opinion the Street Punch is one of those extravagant reliefs from the realities of life which would lose its hold upon the people if it were made moral and instructive. I regard it as quite harmless and as an outrageous joke which no one in existence would think of regarding as an incentive to any kind of action or as a model for any kind of conduct. It is possible, I think, that one secret source of pleasure very generally derived from this performance is the satisfaction the spectator feels in the circumstances that likenesses of men and women can be so knocked about without any pain or suffering.”

I’ve written a little more about Punch & Judy in the appendix.

Show less

There’s still a link of sorts with the puppet today, as over on your right is the Punch & Judy pub, though it’s in a building that dates from two centuries after that first performance took place here.

Nowadays, the area in front of the church is normally busy with the many buskers (or, to use today’s correct terminology, ‘street performers’) for which Covent Garden has become renowned.

It’s now time to visit one of the focal points of this walk – the Covent Garden Market.

The market buildings, which are on your right, are divided into three main sections – the North Hall (and Apple Market), Central Avenue, and the South Hall – each of which runs through from west to east.

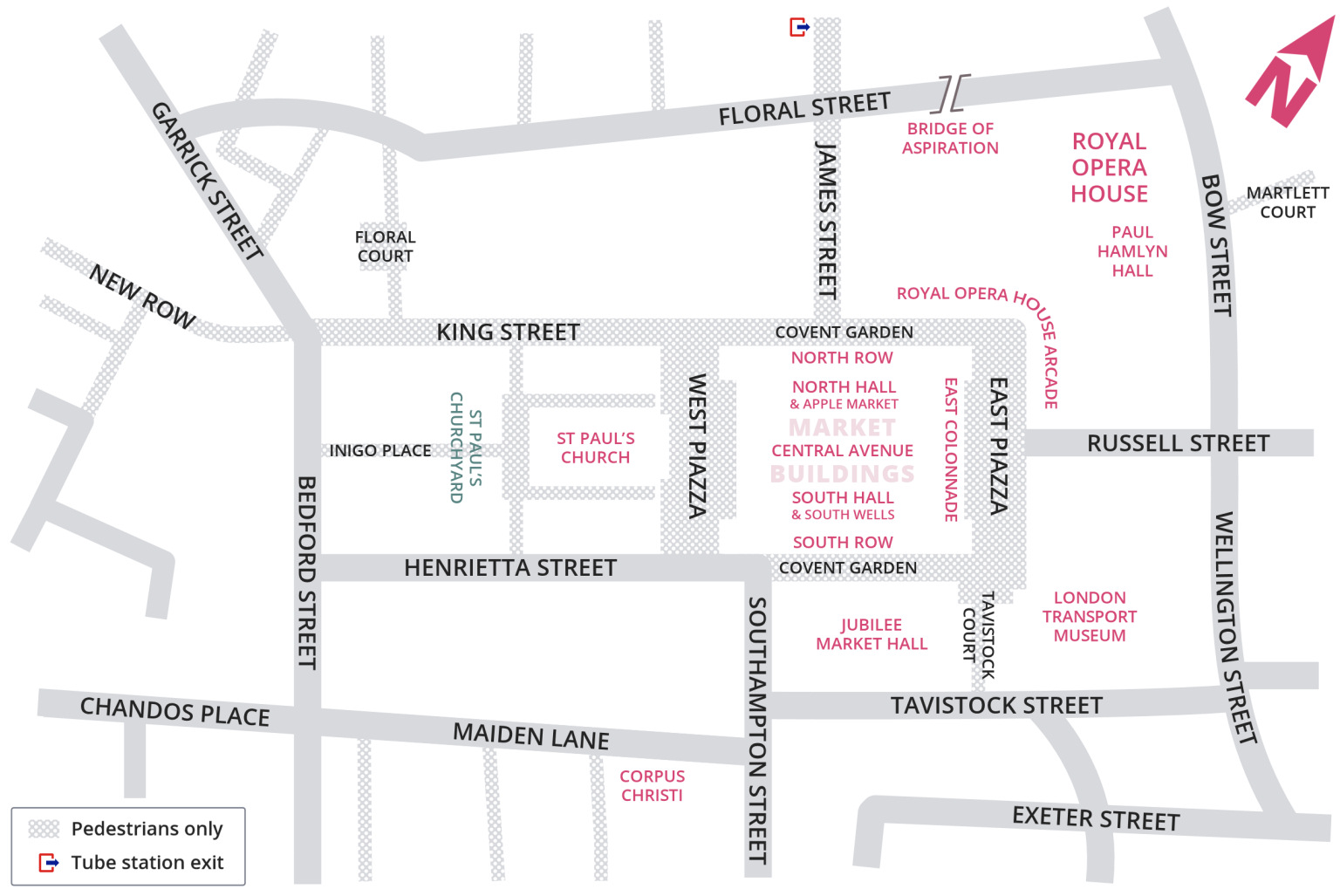

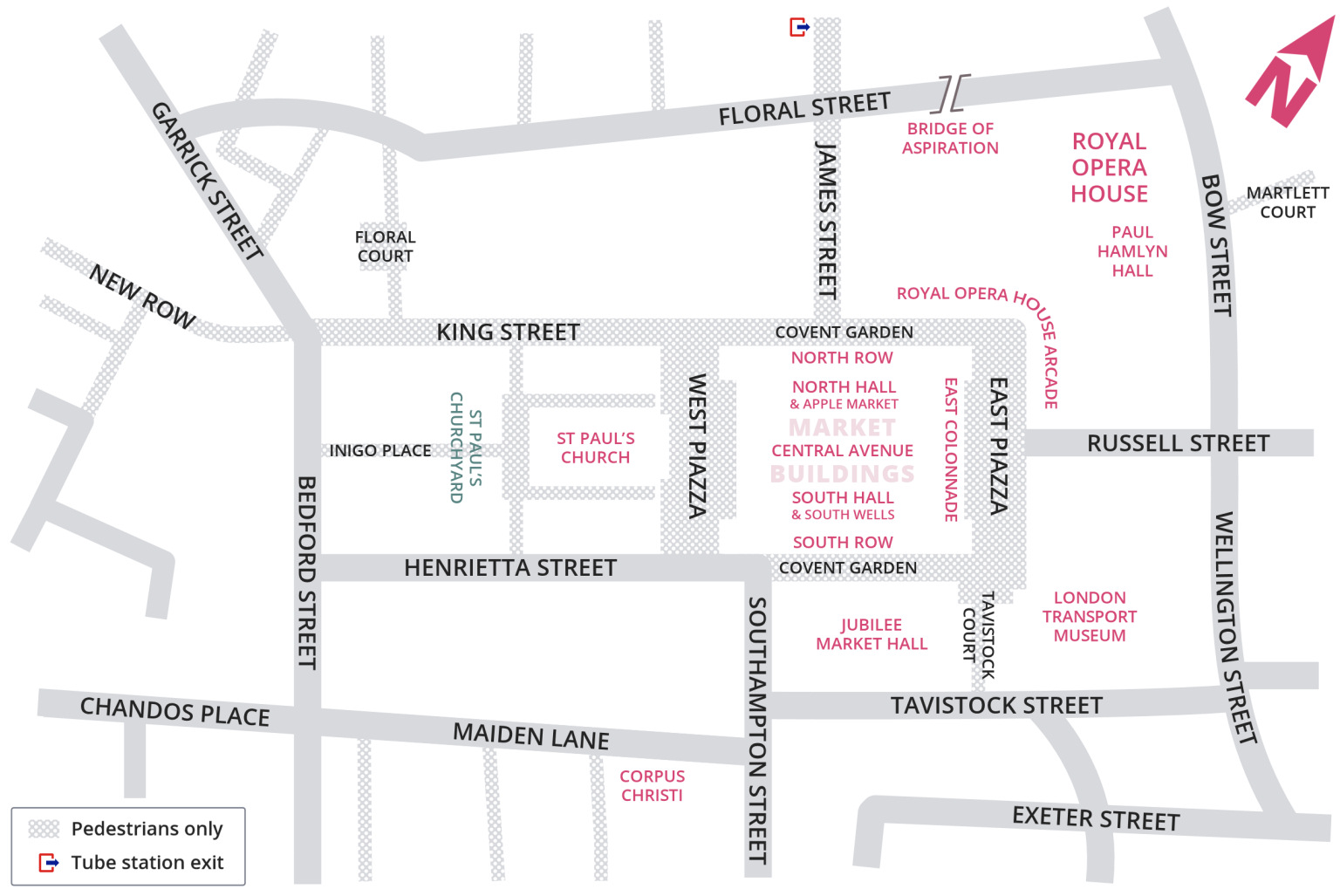

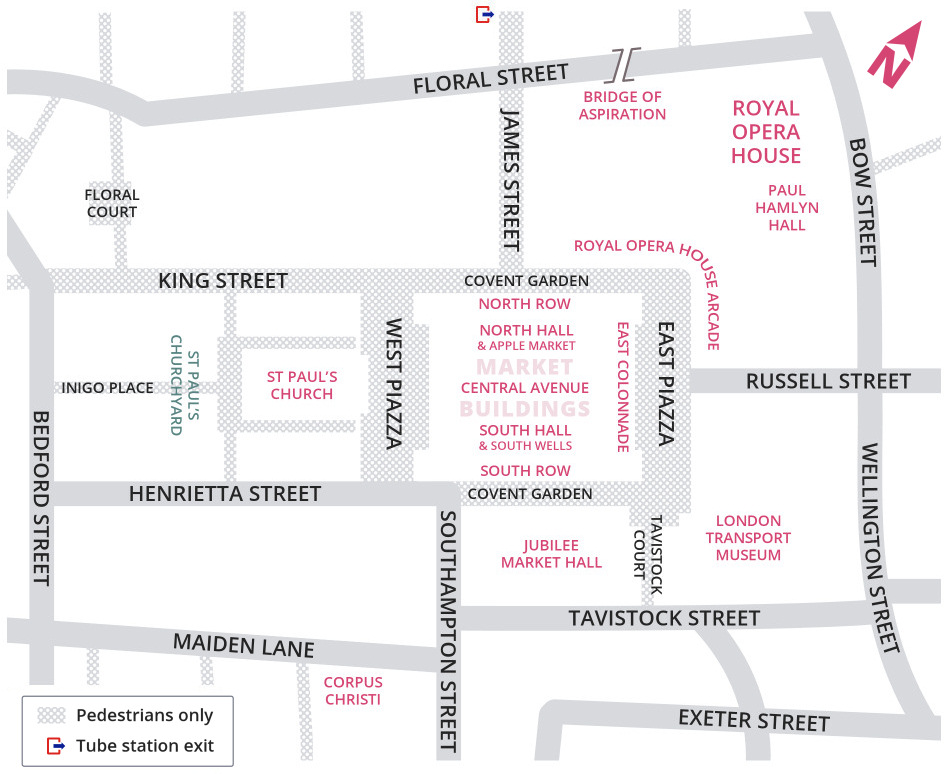

After visiting the market, the walk continues from the opposite (east) side. The map here shows the market buildings and the surrounding area:

From St Paul’s Church, I suggest you enter the market buildings through the North Hall, on the left, with its Apple Market section at the front as you enter.

The Apple Market usually has stalls selling handmade jewellery and other craft items, whilst behind are food outlets – turn right before them and go through the passageway signed Central Avenue. This ‘middle hall’ has rather expensive shops, and unless you are interested, I suggest you carry on through into South Hall, and turn left. (To the right at the end is the entrance to the Punch & Judy pub, whilst on the lower level is a food court, accessed through the pub).

However, turn left and walk through South Hall. Further along is another lower-level food court where there are often live opera or classical music singers performing.

At the end of the halls are a number of stalls and barrows selling a variety of jewellery, crafts, etc. and this brings you out into the open-air East Colonnade. I suggest you pause here for a moment whilst I explain a couple of things before we turn left.

To your right is the excellent London Transport Museum, which opened here in 1980 in the brick and glass building that was built nearly one hundred years before, as part of the flower market.

Much of it is underground and features a fascinating array of horse-drawn carriages, trams, buses and even tube trains that show the history of London’s transport. I don’t suggest you try and find time to visit it now – maybe come back at the end of the walk, or at another time. I will add though that there is an excellent shop selling an enormous range of transport-themed gifts, books, memorabilia, etc., which is free to enter without needing to visit the museum. There is also an excellent upper-level café and toilets as well, and you don’t need to pay to go through the museum to access them. As with the museum, they are open daily for 362 days of the year.

Russell Street branches off at a right angle from the middle of the East Piazza. We don’t walk along this street but it’s worth glancing down it as you pass the junction, with the view of the Theatre Royal at the far end. And on the right, No. 8 is currently Balthazar Boulangerie, a trendy patisserie. From around 1760 this was the newly-built bookshop and home of Thomas Davies, who was a friend of Dr Samuel Johnson, the poet, playwright, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. It was here on 16th May 1763 that Davies introduced Johnson to James Boswell, which began a very long friendship.

Having something of a fascination with Dr Johnson, I give a little more information here:

Still looking down Russell Street you see on the left the enormous and beautifully restored Covent Garden Opera House, which occupies the whole of this block, extending back to Bow Street and north from here to Floral Street, as we shall see shortly. Indeed, with the exception of the ground floor, which is called the Royal Opera House Arcade and occupied by high-end shops, everything above them is part of the opera house. Incidentally, the Royal Opera House Arcade shouldn’t be confused (though it often is) with John Nash’s Royal Opera Arcade, which runs between Pall Mall and Charles II Street in St James’s.

It’s hard to appreciate just how big the opera house complex is until we have walked around it, which we will soon do.

Walk to the top of the East Piazza – the more discreet ‘rear entrance’ of the Royal Opera House is in the right-hand corner of the colonnades. (The main entrance is in Bow Street, which we see shortly). However, if you would like to take a look inside this entrance, there’s an interesting shop, café and, importantly, very nice toilets. I do recommend the opera house guided tour – you need to book in advance – which takes you through many ‘backstage’ areas of the building. You get to see some of the many aspects involved in the production of opera and ballets, for example where costumes, wigs, props and stage sets are made.

If for any reason you have to curtail the walk at this point, then Covent Garden tube station (on the Piccadilly Line) is just ahead at the top of James Street.

Follow the shopping colonnade around to the left and then turn to the right up the wide pedestrianised James Street, where you’ll likely see more street entertainers.

Halfway up James Street turn right into Floral Street. (Yes, this is the same street we were in earlier in the walk – though we are now at the opposite end.)

On both corners of Floral Street are two famous old pubs – the White Lion and the Nag’s Head. The White Lion has been here since at least 1825, though the pub you see today was rebuilt in 1888. It gave its name to a radical political group in the 1820s and 30s – the White Lion Group – as it was where they held their first meeting.

The Nag’s Head is even older in origin, having been on this site since 1670. The present building dates from around 1900 and the Hertfordshire-based McMullen brewery purchased it in 1927. The pub still serves traditional McMullen ales, brewed in Hertford using local malt and whole hops. For many years the pub would open at 5am to serve the many market porters. Unlike the White Lion, the Nag’s Head is Grade II listed.

As with many of the buildings in Covent Garden, those on your left along Floral Street were once workshops and warehouses – notice the large windows, designed to allow in as much light as possible. I’m delighted they have been repurposed rather than being knocked down and replaced with yet more ‘inappropriate’ structures as we see so often in London – it is now the home of the Royal Ballet School. And you can’t fail to notice the unusual bridge – called the Bridge of Aspiration – above, which connects it to the Royal Opera House. Its “award winning design addresses a series of complex conceptual issues and is legible as a fully integrated component of the building it links and as an independent architectural element.” And they’re not my words; they are the words of the architects.

At the end of Floral Street, we are going to turn right down Bow Street (said to have been so named because of its “curved course” – though it certainly doesn’t look bow-shaped to me) – but before you do, across the road you’ll see a life-size sculpture of a female dancer, located under a tree in the wide entrance to Broad Court.

The beautiful bronze sculpture of a ballerina was installed here in 1988 and called Young Dancer. Sculpted by Enzo Plazzotta, an Italian who loved ballet, it pictures the dancer seated on a stool. Her right leg bent slightly at the knee, points to the ground with her toe just touching. Her left leg is across the right with her hands resting on it. She has a calm look and appears to be resting.

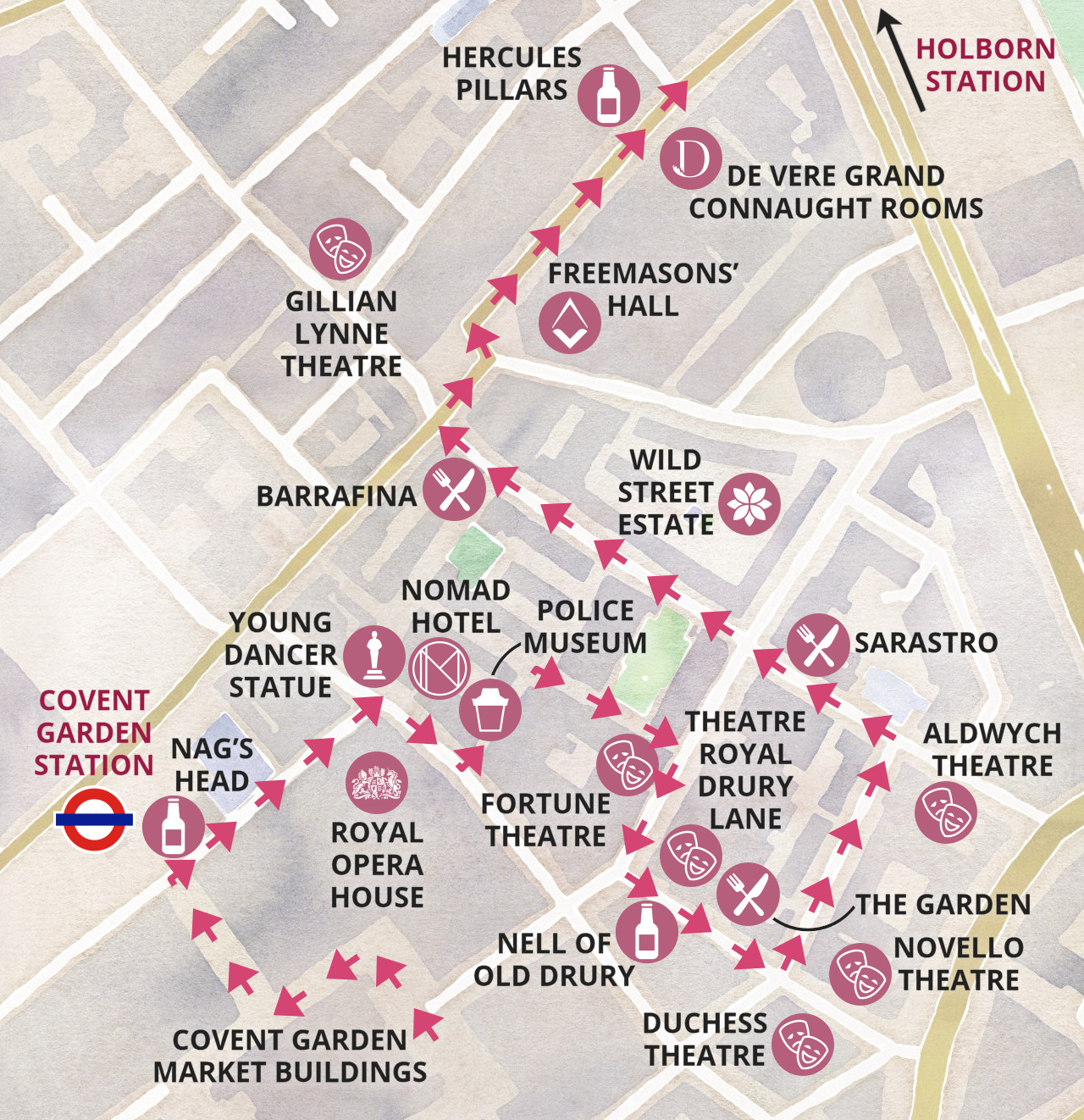

Walk down on the left side of Bow Street, passing the famous Bow Street Magistrates Court. It opened some 270 years ago, though on the side of the road where the Royal Opera House is today. It moved across into the purpose-built court building with the adjacent police station in 1881.

The police station closed in 1992, followed by the court in 2006 and the building remained boarded up for many years. However, it has now been converted into the five-star 90-room NoMad Hotel, at a cost of over £50 million. (Rooms here start at around £500 a night and up to £2,500 a night for the Royal Opera Suite).

Those who were more reluctant visitors (to the magistrate’s court and not the hotel, I would hasten to add) have included Oscar Wilde, the murderer Dr Crippen, the East End gangsters the Kray twins, the suffragette Pankhurst sisters, Second World War traitor William Joyce (otherwise known as Lord Haw Haw) and Lord Jeffery Archer.

Another high profile ‘guest’ here in 1968, was James Earl Ray. He had assassinated civil rights activist Martin Luther King Junior and fled to Canada and then came to London. He was stopped at passport control at Heathrow Airport and brought to Bow Street for possession of false documents, as well as a firearm. He was then extradited to the US, where he was tried and sentenced to 99 years in prison for the murder. Bow Street court was also where a number of members of the IRA, who were facing terrorism charges, appeared.

Many people appeared before the magistrates here because it was a ‘legal gateway’ to the Old Bailey and the Crown Courts. What also gave these courts their unique status was that it dealt with such serious matters as terrorist offenses, extradition cases and prosecutions under the Official Secrets Act.

Adjoining the courts was the equally famous Bow Street Police Station, home of the Bow Street Runners, the forerunners of today’s modern police forces, and there’s a small museum that gives more information about them around the corner in Martlett Street.

Before we turn left, look across at the magnificent frontage of the Royal Opera House.

Take the next left into Martlett Court and on the left is the entrance to the Bow Street Police Museum. This small museum explains how the Bow Street Runners became Britain’s – and possibly the world’s – first organised police force. Much of the story is told using information boards, but you visit one of the original cells, including the larger one known as the ‘holding tank’ where the drunks and disorderly were put for the night before appearing in the morning before the magistrates. You can also see one of the docks from the original court rooms whilst other exhibits include a cutlass that was used by the early Bow Street runners, various truncheons, early policemen’s notebooks, etc. It’s open Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays from 11am to 4.30pm.

Facing you at the end of the street is Fletcher Buildings, one of the many huge social housing buildings in this area. We pass several others shortly and I explain more then.

Turn right down Crown Court, passing an unusual building on your right. I say unusual, as it contains both a church and a theatre – the entrance to both the church hall and the stage door are here, whilst their main entrances are around the corner in Russell Street, where we walk next.

This is the ‘Crown Court Presbyterian Church of Scotland’, which was built in 1711. Back then the church owned the entire building, but in the early 20th century it was purchased by the Fortune Theatre. The church was allowed to stay, though much of it being rebuilt in 1909.

Turn right into Russell Street, passing the entrance to both the Fortune Theatre and the church – the latter being a fairly insignificant wooden door with a stone cross above it.

The Fortune Theatre, called a ‘jewel of a theatre’ and designed in the beautiful art deco style, opened in 1924 and was one of the first buildings in London to be built in concrete.

It sits on the site of the ancient Albion Tavern, said to have been a haunt of actors and playwrights. It was named after the Fortune Playhouse (in turn named after the Roman goddess Fortuna), which had opened in 1600 in Cripplegate, just outside the jurisdiction of the City of London and where Shakespeare himself may have performed.

From August 1989 until March 2023 the theatre hosted the horror-mystery play The Woman in Black. Seen by two million people, it was London’s second longest-running non-musical play after The Mousetrap.

However, the Fortune Theatre is dwarfed by the Grade I listed Theatre Royal Drury Lane opposite. Cross over and walk along under the colonnade with its gold tipped railings and turn left down Catherine Street.

Notice the drinking fountain on the corner. It is a memorial to Sir Augustus Harris, the manager of the Theatre Royal Drury Lane during its heyday from 1873 to 1896. He played a huge part in its success during this time, but sadly died of exhaustion at the early age of forty-four.

The Theatre Royal (its ‘Royal’ title is because it was one of just two theatres given a royal patent by Charles II) is London’s third largest theatre, with seating capacity of over 2,000. It is the fourth theatre to be built on the site, the first opening in 1633, making it the oldest in London (at least by one definition). This was a three-tiered wooden structure which could accommodate 700 people. To allow in daylight (no stage lighting in those days) there wasn’t a roof and performances usually began at 3pm to take advantage of whatever light there was. It burnt down in 1672, and two years later a new theatre was built. The theatre we see today was built in 1812, though there were considerable renovations in the 1920s.

The theatre was purchased by Andrew Lloyd-Webber in 2000 and to mark the theatre’s 350th anniversary in 2013, he began a major £4 million restoration. This returned some of the original features of the theatre back to their Regency style.

From the theatre continue on down Catherine Street. Notice alongside the theatre a delightful café/bar called The Garden at the Lane. It’s in a narrow, covered passageway and is open from 9.30 in the morning, serving coffee, brunches and afternoon refreshments and in the evenings cocktails and light snacks.

Opposite the theatre is another of London’s many fascinating pubs, the Nell of Old Drury, named after Nell Gwynne, the Covent Garden orange seller who became a famous actress and then mistress of Charles II. Whilst this isn’t the original pub, there has been one here since the late 16th century.

Also on that side is the Opera Tavern. There’s been a pub on the site since 1791, when it was called the Yorkshire Grey, and later the Sheridan Knowles. It was renamed the Opera Tavern in 1861 and rebuilt in its present form in 1879. I like its striking grey façade – but it wasn’t always so plain. In 1970 the Covent Garden volume of the Survey of London said: “The narrow front is a design of extremely eclectic character, the wilful distortions of standard Italianate and neo-classical motifs made even more striking by the present application of bold colour.”

Take the next left into Tavistock Street, alongside the Novello Theatre, whilst on the other side is the Duchess Theatre – not without good reason is this area known as ‘London’s theatre district’.

The nondescript building on your right with the ‘New York style of iron outdoor fire escapes’ is the rear of the Waldorf Hotel, though from here you wouldn’t realise it had five stars.

On the left are the Stirling Buildings, one of a number of apartment buildings that were built by the Peabody Trust in the late 19th century, and still run today by the Peabody Trust housing association. A resident of Stirling Buildings who I chatted with outside told me the flats were a mixture of one, two and three-bedrooms, and that they’d all been refurbished several times since being built around 1881. She added that whilst some were still rented on a social-housing basis, many had now been purchased. I’ll say more about the man behind the Peabody buildings when we come to his next development.

Back in the 1970s the Greater London Council were desperately trying to demolish much of Covent Garden (which I’ve referred to elsewhere) and Stirling Court was one of many planned to go under the ‘wrecker’s ball’. The building, together with others nearby, were to be knocked down in order for a four-lane road to go through here, as well as to build an extension to the adjacent Waldorf Hotel. They even got as far as evicting tenants, giving them just £30 to cover their expenses. However, extensive campaigning, including protest marches and picketing, eventually saw the council retract their plans and these, together with many other buildings within the central Covent Garden area, are fortunately still with us today. (I’ve previously explained more about the work of the conservation groups who did so much to ensure that Seven Dials and Covent Garden was saved from demolition and subsequent modern development.)

Pass the stage door of the Aldwych Theatre on the right and turn left up Drury Lane. Facing you is the St Clement Danes Church of England Primary School. As the frieze inscription states, the school was founded in 1700 and rebuilt in 1907. (St Clement Danes Church is situated a few minutes’ walk away in the Strand, and I explain more about its history in my Charing Cross to St Paul’s walk.)

Should anyone be particularly interested in the school’s history, there is a very comprehensive (60 pages!) document about it that’s available online here.

Drury Lane, like much of this area, has had a long and at times troubled history. For a start, it is here that the Great Plague of 1665–6 was said to have begun.

Read more about the plague in Drury Lane …