Updated: 25 July 2024 |

|

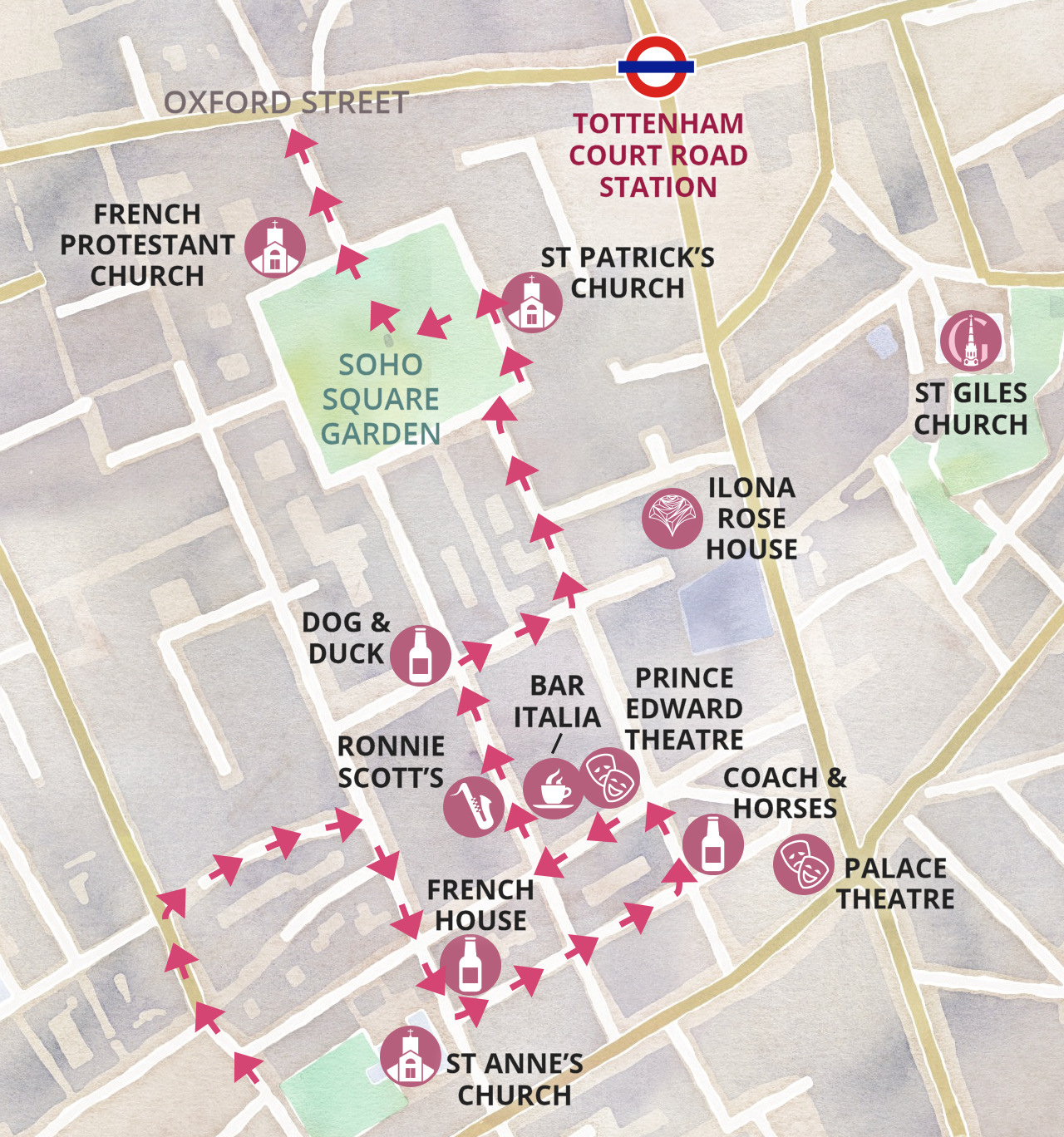

Length: About 2¼ miles |

|

Duration: 3 – 3½ hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

A walk around Soho

INTRODUCTION

Soho is central London’s most cosmopolitan and diverse area. It’s got a fascinating history – and it also happens to be one of my favourite areas of the city.

With so much of interest packed into such a relatively small area, it’s been the most challenging and time-consuming of my walks to research and write so far. There is something of historical or distinctive interest every few steps.

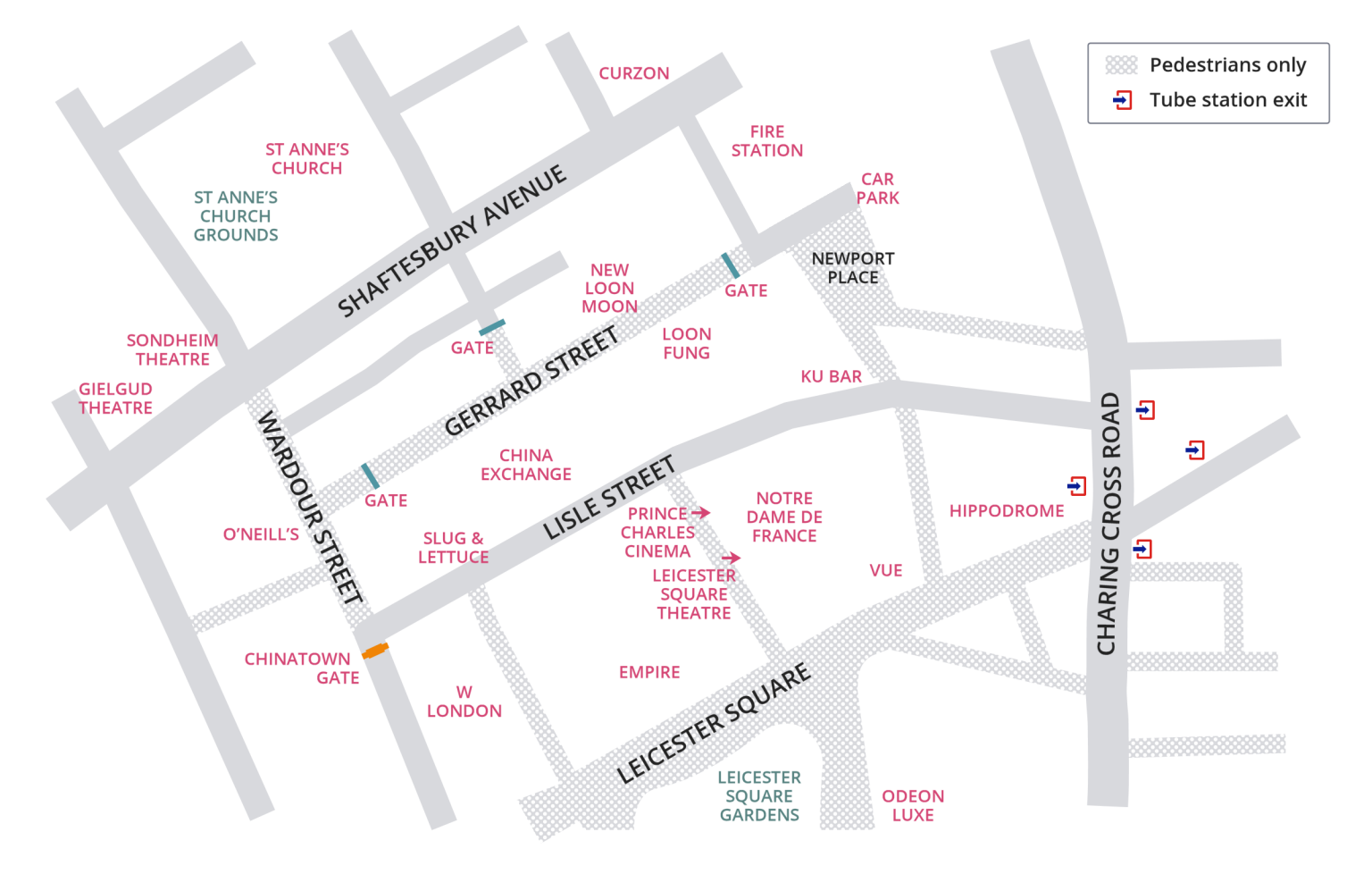

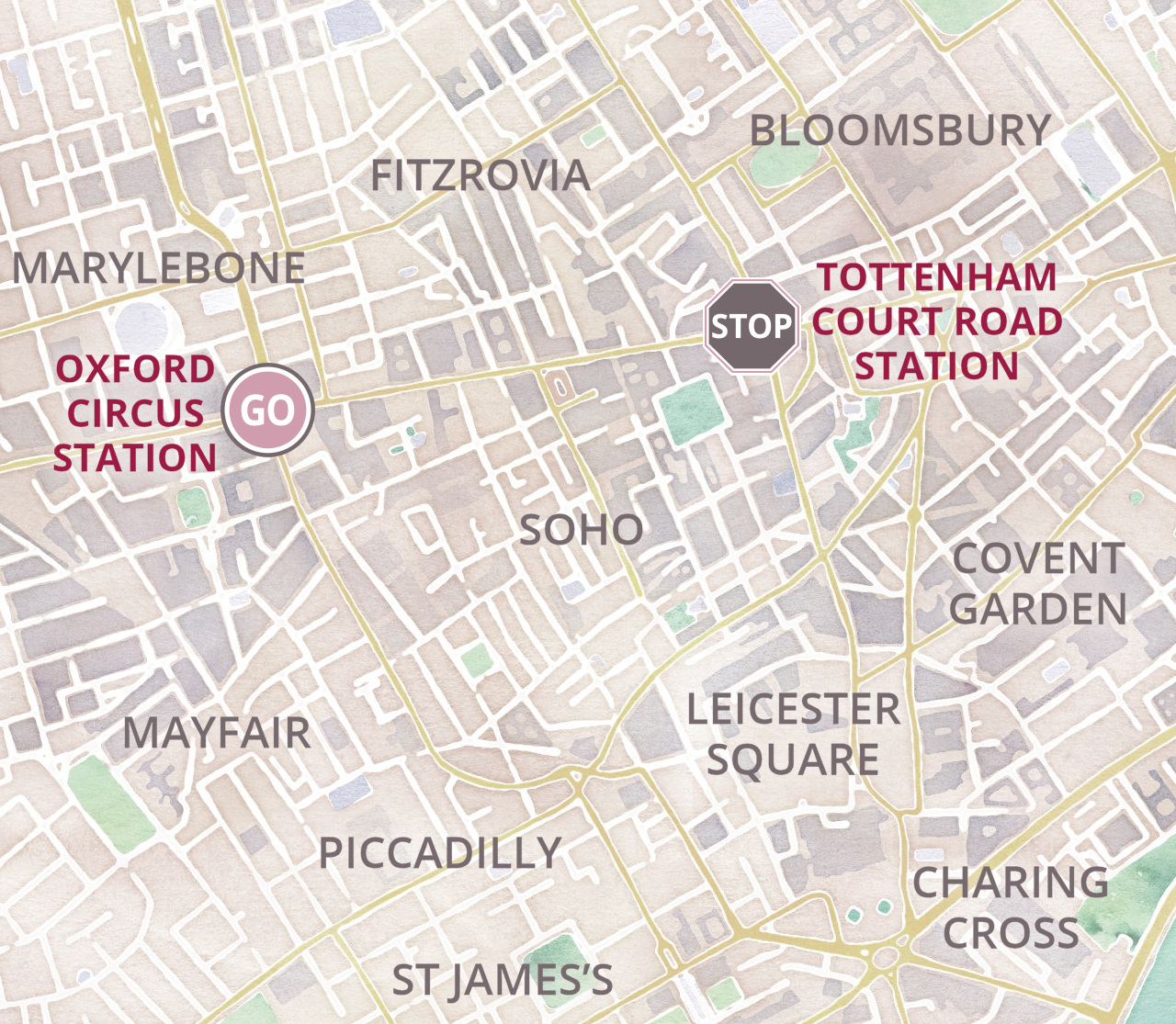

It’s a neatly defined area, bordered by Oxford Street to the north, Regent Street to the west, Charing Cross Road to the east and Coventry Street, which runs from Piccadilly Circus to Leicester Square.

Highlights of the walk include Liberty’s, Carnaby Street, Piccadilly Circus, Leicester Square, Chinatown, Wardour Street, Ronnie Scott’s jazz club and Soho Square. There are Grade I listed structures in Piccadilly Circus (Eros), Dean Street (Nos. 26–28) and Greek Street (No. 1).

Start: Oxford Circus |

|

Finish: Tottenham Court Road station |

GETTING HERE

Oxford Circus is served by the Bakerloo, Central and Victoria tube lines. It is also on a number of bus routes, including the 12, 22, 88, 94, 139, 159.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SOHO

In the Middle Ages this was just farmland, later becoming Henry VIII’s hunting grounds (the name ‘Soho’ is an old hunting cry, like ‘Tally Ho’). It began to be developed in the mid-17th century, and initially the houses were quite grand and inhabited by the wealthy and influential.

Then came influxes of refugees, mainly Huguenots from France, but others from Russia, Germany and Italy fleeing both poverty and religious and political persecution. This resulted in the ‘gentry’ moving into posher areas such as Mayfair. Indeed, by the early 18th century between a quarter and a half of the population of Soho were French, and in 1740 a commentator wrote, “Many parts of this parish so greatly abound with French that it is an easy matter for a stranger to imagine himself in France.”

One of the results of the huge mix of people who lived in Soho over the years is its cosmopolitan atmosphere. This has attracted a diverse population, particularly from the worlds of the arts, literature, cinema and music. Just a few examples are the Hungarian composer Frank Liszt, the painters Canaletto and Constable and the ‘romantic’ Italian writer and adventurer Casanova. William Blake, Percy Shelley and Karl Marx also lived here.

Fast-forward to the 20th century and Soho has been at the centre of Britain’s – and at times the world’s – music and fashion trends. This was where nearly all the top bands of the 50s, 60s and 70s played their first major gigs. And when it comes to fashion – well, teenage fashion was virtually invented here. Who hasn’t heard of Carnaby Street, which we visit on the walk?

Soho has always been the centre of London’s entertainment, but that brought with it the ‘sleazy’ clubs and prostitution, for which the area became known. However, action by the local authority and the police in the 1980s saw a major clean-up operation. Now, Soho is one of London’s most popular areas for theatres, bars and restaurants. It has also become the heart of London’s LGBTQ+ scene, offering many gay and bi-friendly bars and clubs.

On this walk you will hear and see more about the many periods, people and events that have made Soho so famous.

STARTING THE WALK

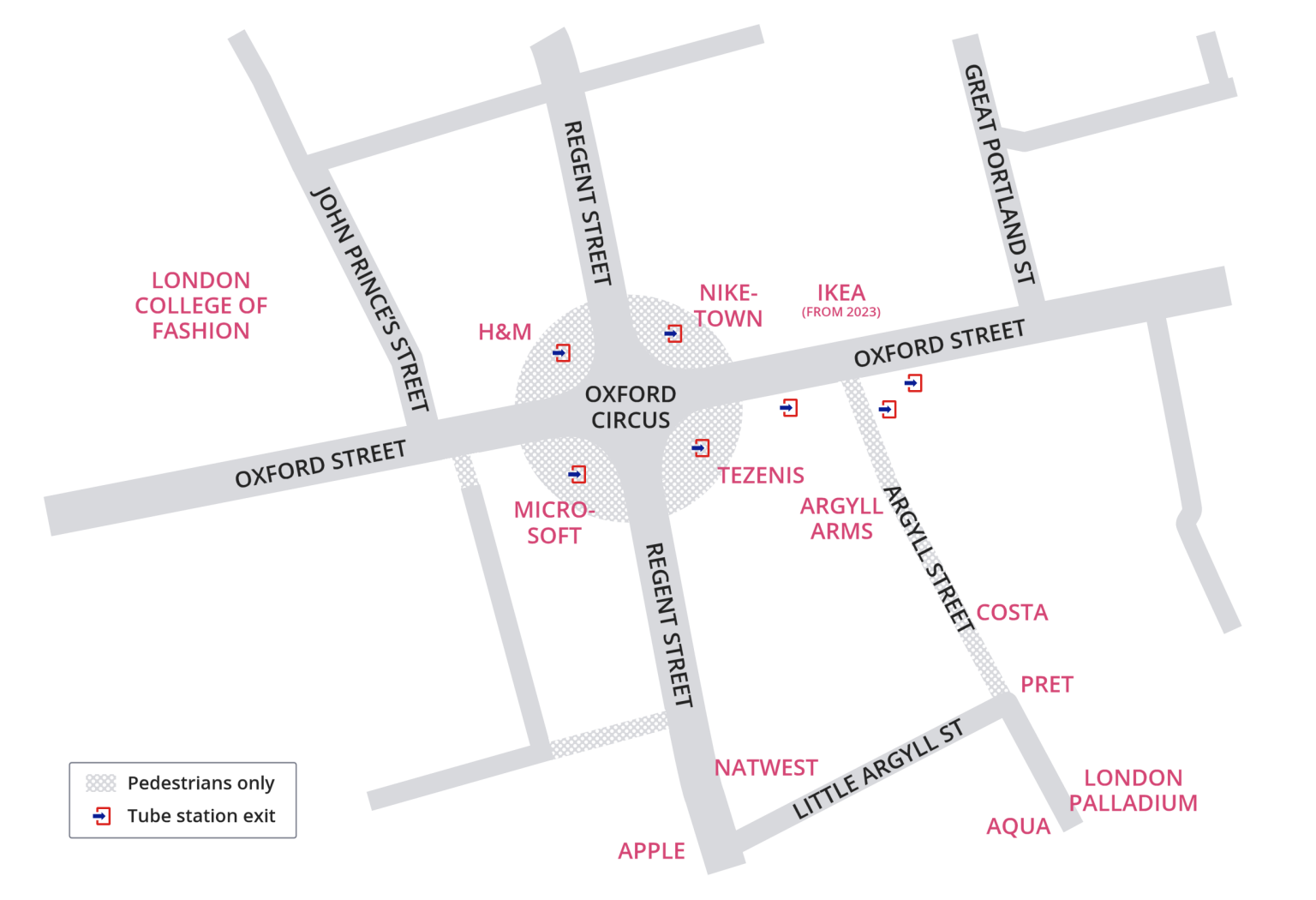

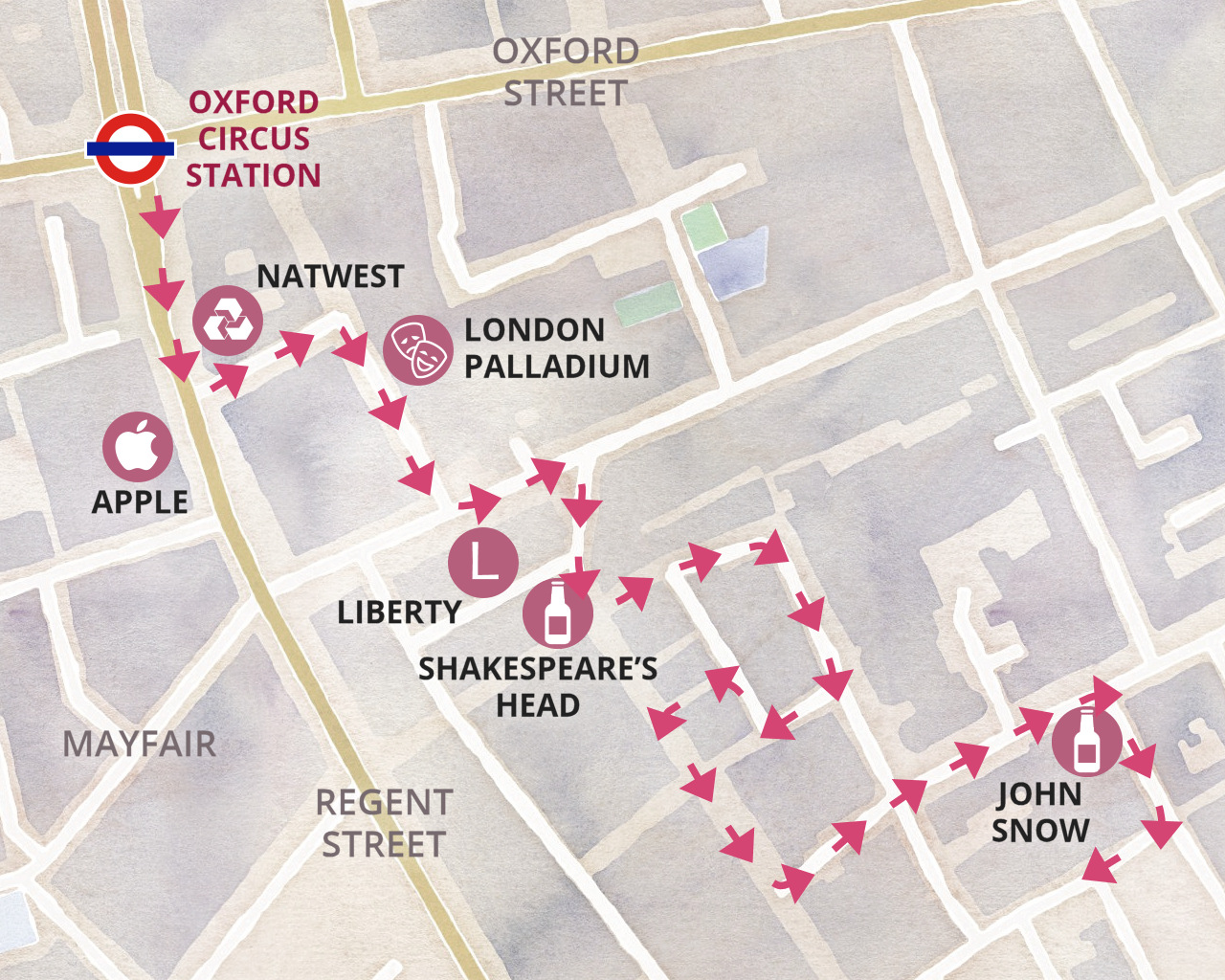

The walk begins at Oxford Circus, one of London’s best-known locations.

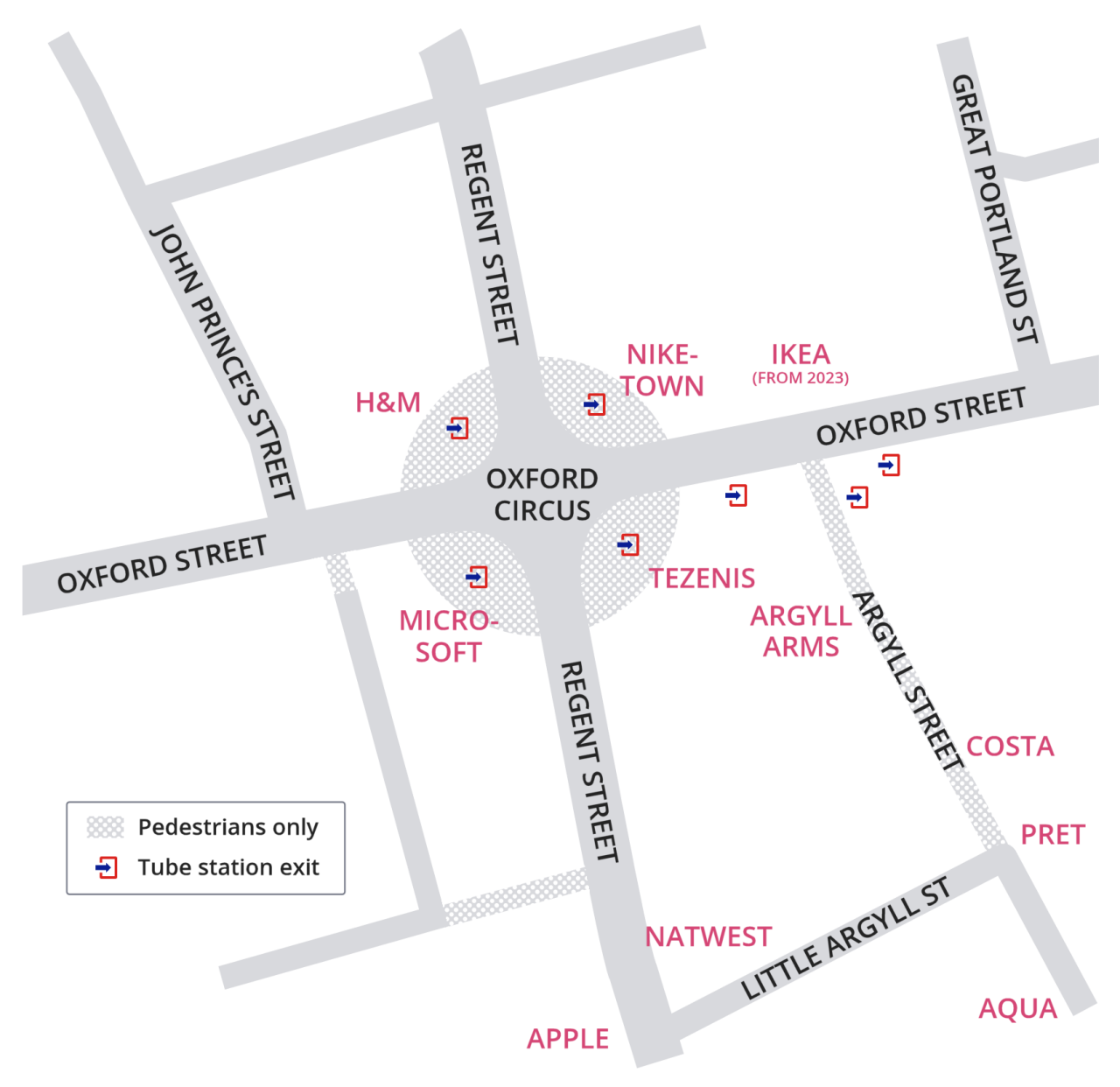

We start at the south-east corner – see the map below for more details, and if you arrive at Oxford Street tube station, then leave via Exit 5.

As you emerge from the station turn left and walk 15 yards and you find yourself standing at the crossroads of two of the world’s most famous shopping streets – Oxford Street and Regent Street. The first runs from west to east, whilst Regent Street from north to south.

I particularly like the architectural design of the buildings on each of the four corners, as they ‘fit together’ to help create a circular effect. This is particularly the case with their roof lines.

For many years the northeast corner building was occupied by the famous department store ‘Peter Robinson’ and when it closed it became the UK’s biggest branch of Top Shop. However, in a move that surprised most people and is said to have cost in the region of £385 million, the site, together with the adjacent Nike store, has now become an IKEA that covers the equivalent of three and a half football football pitches.

Looking up Regent Street to the north you can see All Souls Church and behind it the famous BBC building, Broadcasting House.

On the south-west corner of Oxford Street (west) and Regent Street (south) is the Microsoft store.

We start by turning left down Regent Street (south) but keeping to the left-hand side of the road.

A few words about Regent Street, which divides Mayfair from Soho. It was commissioned by the Prince Regent (who later became King George IV) who wanted to build a ‘ceremonial route’ from Carlton House (which was then his home) to connect with his plan for a park, to be known as Regent’s Park. He employed the architect John Nash to achieve it, which he did.

However, it did not quite go to plan – the Prince had wanted Regent Street to be straight, but because much of the land was privately owned, that couldn’t be achieved, hence its curve. Initially much of the street had colonnades on each side and whilst this protected shoppers from the rain, it wasn’t popular with the shop owners. They complained that it reduced the light and, in the evenings, encouraged prostitution. As a result, the colonnade was demolished, and the street today looks surprisingly similar to how it must have looked back then.

I’ll just mention here that there are some magnificent buildings along the length of Regent Street – we see a couple at the very beginning of the walk, particularly the Apple store, which I highlight shortly.

After just fifty yards notice on the wall of the NatWest bank a plaque which explains that this was once the site of the Argyll Rooms, one of London’s finest concert halls until it burnt down in 1830. It was here in 1824 that the 12-year-old Franz Liszt made his London debut and the following year that Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (also known as the Choral Symphony) was first performed in Britain. And just five years later, it was where Mendelssohn gave his first London concert.

We’re going to take the next left alongside the NatWest into Little Argyll Street.

However, before you do, I suggest you look across to the other side of Regent Street. Most of the buildings in Regent Street are impressive, with some amazing architecture. A good example is the Apple store, which is directly opposite you – just notice its large, arched windows and rather beautiful domed roof. (There’s no sign saying ‘Apple’ – just their large ‘apple-with-a-bite-taken-out’ flag hanging over the front).

It’s one of the oldest shops in Regent Street, having been built in 1898 by Salviati & Jesurum of Venice to display the glass and fabrics they made in Murano. An example of their mosaics can still be seen today on the front of the building, which feature the heraldic shields of the islands of Burano, Murano and Venice. In a red and gold mosaic band are the names of the other cities where the company also had shops – ‘Paris, New York, St Petersburg and Berlin’. (Other examples of the company’s wonderful mosaics can also be found in St Paul’s Cathedral.)

The new Apple store was redesigned by Foster+Partners, whose amazing architectural works elsewhere in London, and indeed across the world, are too numerous to list here.

At the end of Little Argyll Street turn right into Argyll Street where you immediately see the impressive frontage of the London Palladium. Look up at the building to the left of the Palladium and you’ll see a plaque explaining that the American writer Washington Irving lived there in the 1780s.

Opposite the Palladium is Aqua Kyoto – one of my favourite bar/restaurants in London. Situated five floors above what was once the Dickens & Jones department store, it has two restaurants, a cocktail bar and a stunning roof terrace overlooking Regent Street where you can enjoy an al fresco drink. (Access is via a lift in the lobby.)

Facing you at the bottom of Argyll Street is Liberty’s, the distinguished department store. Before we turn left along Great Marlborough Street walk 50 yards to the right to take a look at three-storey archway adjacent to Liberty’s that spans Kingly Street. I assumed it must have at one time linked with the adjoining building, but it doesn’t and the room above the arch simply provides more retail space, as the photo here shows.

I love the recently restored Liberty’s clock, with its message that I’m sure is good advice to us all – ‘No minute gone comes ever back again – take heed and see ye do nothing in vain’.

It’s worth taking a brief look inside the store as its interior is still as magnificent today as it must have been when it opened. The main entrance is at the front of the store, through the florists and between the two lions.

Liberty’s is something rare these days – a department store whose traditions and quirkiness have hardly changed over the years. It was opened by Arthur Liberty in 1874 in Regent Street, selling fabrics and ornaments from Japan, the Far East and India, but became so successful that it in 1924 he moved to the much larger and more prestigious building that we see today in Great Marlborough Street.

The new store was built in the Tudor-revival style that was popular at the time, using the timber from two ancient battleships. Indeed, the deck planks from the ships created the well-worn but beautiful wooden flooring that’s still in use today. Built over six floors, with three atriums surrounded by smaller rooms, it was an immediate success with customers. Always at the forefront of fashion, Arthur Liberty used to say, “I was determined not to follow existing fashion, but to create new ones.”

After Liberty’s, turn back to continue along Great Marlborough Street, passing on the left the stage door of the London Palladium, where thousands of pop fans have gathered in the past to see their heroes.

Before we take the next right into the wide entrance that leads into Carnaby Street, notice also on the left what was once the Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court. Many hundreds of well-known people, including Oscar Wilde, John Lennon, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards have been tried here. It’s also where in 1835 Charles Dickens once worked as a court reporter for the Morning Chronicle. The original court opened here in the early 1800s, the second oldest of the seven police stations and magistrates’ courts in England (the first being the Bow Street Court in Covent Garden). However, it was rebuilt in 1913, which is the building we see today. It’s now been converted into the expensive, five-star Courthouse Hotel.

Turn right down to Carnaby Street, and you will soon pass the Shakespeare’s Head pub, established in 1735 and originally owned by Thomas and John Shakespeare, who were supposedly distant relatives of William Shakespeare. The pub’s sign is a reproduction of a portrait of Shakespeare, painted when the Bard was at the height of his popularity. Look up at the ‘window’ on the front corner of the building and you can see Shakespeare himself gazing down on the street. But notice his right hand is missing; it is said to have been blown off by a bomb in the Second World War. However, one sceptical commentator suggests that almost every claim made about this pub’s history is untrue. Either way, its premises were certainly rebuilt in 1927 and no trace of any earlier structure remains.

Turn left into Foubert’s Place – pass Newburgh Street on the right (where shortly we see the site of the men’s shop that kicked off the Carnaby Street fashion scene in the 1950s.)

At the end of Foubert’s Place notice the large brick building that was once the Craven School and Lecture Hall, now used by a film production company.

Facing you as you turn into Marshall Street is a block of well-restored ‘City of Westminster Dwellings’.

Next to them you certainly can’t miss the imposing Marshall Street Leisure Centre. Opened in 1931 and now Grade II listed, it contains the original magnificent 100ft long swimming pool with its barrel-vaulted ceiling and marble floors. It’s now owned by Everyone Active, part of the Sports and Leisure Management Company that runs facilities such as this on behalf of local authorities. It now offers a spa, exercise studios, gym, etc. Curiously, the high-ceilinged baths were used by the American forces in the Second World War for training parachutists.

Take the first right into Ganton Street then turn right into Newburgh Street. On your left is the White Horse pub. There has been a pub on this site since the early 1700s, when Soho was being developed. The pub we see today was built in the 1930s, with an art deco exterior and panelled interior.

We’re going to turn left alongside the pub into Marlborough Court – but I’ll mention first that on the right at No 5 Newburgh Street was the site of the men’s fashion shop called ‘Vince’ which, in the early 1950s, was the beginning of neighbouring Carnaby Street becoming world-famous for ‘trendy men’s fashion’. Many of Vince’s customers were gay, as indeed he was, and would meet at the Marshall Street baths we’ve just passed, then a popular meeting place for gay men.

However, the person really responsible for Carnaby Street’s worldwide fame for fashion was a young man by the name of John Stephen. He had only worked for Vince for a short time before leaving to open up his own boutique on nearby Beak Street. It was called ‘His Clothes’ and then shortly after he opened a second at 5 Carnaby Street. Although his merchandise targeted teenagers, it attracted high profile pop stars including Jimi Hendrix, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the Kinks. John Stephen went on to open a further 5 shops on Carnaby Street.

Besides adding more information in the next section, I’ve also written more about Bill Green and John Stephen and the growth of Carnaby Street in the appendix.

At the end of the very short Marlborough Court turn left into Carnaby Street and carry on down until you reach Broadwick Street.

We’re going to turn left into Broadwick Street, but two things to look out for before you do. Firstly, notice on the right-hand side of Carnaby Street a small ‘art deco’ sign over a discreet entrance passage into Kingley Court. It’s a covered courtyard with three floors of bars and restaurants – worth taking a look even if you’re not planning on eating. (Kingley Court was at one time home to Tatty Bogle, one of London’s earliest out-of-hours drinking clubs, which had originally been opened by a group of Scottish officers in nearby Frith Street before moving here.)

Then as you turn left into Broadwick Street you can’t miss the huge, colourful mural. Called ‘The Spirit of Soho’, this 1,600 square foot (approximately – I haven’t been able to determine the exact size) mural was erected here in 1991 and constructed of colourful mosaics and produced by a collective of Soho based artists who wanted to give a visual background to the area’s vibrant and colourful past, highlighting some of the places and people that had made it so unique.

Cross Marshall Street, continue along Broadwick Street (which used to be just called Broad Street), passing a well-restored row of terraced houses, until you reach Lexington Street.

On the corner is the John Snow pub (c.1870), named after a most remarkable doctor who, thanks to his painstaking research into how cholera spread and then his persistence in trying to persuade the authorities to believe him, eventually saved countless lives. Outside the pub is a replica of the pump that he identified as the source of the cholera. Notice, it’s without the handle that would have once pumped the water up. It was by persuading the authorities to remove the handle of the pump – and quickly seeing the number of cases of cholera dropping – that he proved it was a waterborne disease.

Turn right down the side of the pub into Lexington Street – then take the next right into Beak Street.

Beak Street was laid out around 1680 and is named after its developer Thomas Beake, who later became a servant of Queen Anne.

As you walk along Beak Street you see on the corner of Great Pulteney Street another famous Soho drinking establishment – The Sun and Thirteen Cantons. A pub has existed on this site since 1756; the previous one called The Sun burnt down in the late 1870s. It was replaced by the one you see today, which opened in 1882 and is Grade II listed. When it reopened the ‘Thirteen Cantons’ was added to the name in acknowledgment of the Swiss watch makers and woollen merchants who lived and worked nearby. (The Thirteen Cantons were the sovereign territories of early modern Switzerland.) The pub has always been a major hangout for film and stage celebrities, including the likes of Peter O’Toole, Jude Law, Oliver Reed, Ewan McGregor and Russell Crowe, amongst many others.

In 1791 Joseph Haydn, known as the ‘father of the symphony’, lived in a house just a few doors down in Great Pulteney Street. He became particularly popular in the city after composing his twelve London Symphonies.

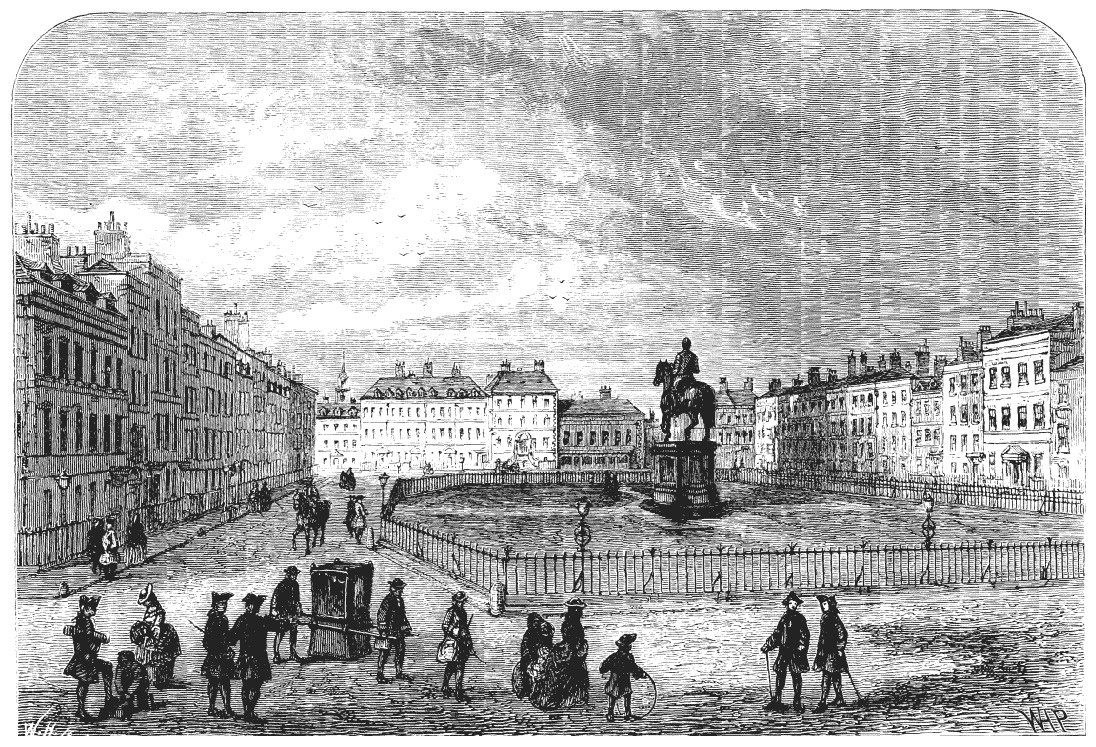

Continue along Beak Street, crossing Bridle Lane and take the next left into Upper James Street. It’s not a particularly interesting street, but a little way down it runs into the left-hand side of Golden Square, one of the first areas of Soho to be developed. It’s had a very mixed history, as I explain next, but today it hosts the offices of a number of media companies.

Charles Dickens chose Golden Square as the setting for Ralph Nickleby’s gloomy house in ‘Nicholas Nickleby’ in 1839:

“Although a few members of the graver professions live about Golden Square, it is not exactly in anybody's way to or from anywhere. It is one of the squares that have been; a quarter of the town that has gone down in the world and taken to letting lodgings. Many of its first and second floors are let, furnished, to single gentlemen; and it takes boarders besides. It is a great resort of foreigners. ... Its boarding-houses are musical, and the notes of pianos and harps float in the evening time round the head of the mournful statue, the guardian genius of a little wilderness of shrubs, in the centre of the square. ... Street bands are on their mettle in Golden Square; and itinerant glee-singers quaver involuntarily as they raise their voices within its boundaries.”

“Although a few members of the graver professions live about Golden Square, it is not exactly in anybody's way to or from anywhere. It is one of the squares that have been; a quarter of the town that has gone down in the world and taken to letting lodgings. Many of its first and second floors are let, furnished, to single gentlemen; and it takes boarders besides. It is a great resort of foreigners. ... Its boarding-houses are musical, and the notes of pianos and harps float in the evening time round the head of the mournful statue, the guardian genius of a little wilderness of shrubs, in the centre of the square. ... Street bands are on their mettle in Golden Square; and itinerant glee-singers quaver involuntarily as they raise their voices within its boundaries.”

Continue down through Golden Square (Upper James Street becomes Lower James Street) and at the bottom, you’ll see the Crown, a pleasing 19th-century pub. There’s a plaque on its wall claiming that this was the site of Hickford’s Room, once a well-known music venue, but the room was actually on the south side of Brewer Street, roughly where the Colmar fashion shop now stands, at No. 63. (Perhaps the pub’s landlord was confused by historical documents saying the site of Hickford’s Room belonged to the Crown – but this would have been a reference to the Crown Estate, custodian of the monarch’s landholdings.)

Hickford’s Room had previously been in Panton Street, but in the 1730s it relocated to Brewer Street, and for a few years was the most important concert hall in London’s West End. Handel performed here on a number of occasions, whilst in 1756 the nine-year-old Mozart and his elder sister gave a concert that included pieces of his own composition. (At nine years old!)

The room was said to have been “large and finely proportioned,” though it wasn’t really big – being around 50 feet long, 27 feet wide and 22 feet high. Within a few years, other larger and more prestigious concert halls were built in London, particularly Mrs Cornelys’ Rooms in Soho Square (we see the site of it later in the walk). Hickford’s then became used for less important events, including performances by schools and even dancing academies. In 1934 it was demolished for the construction of an annex of the Regent Hotel.

Cross over Brewer Street and continue down Sherwood Street, passing under the bridge that once linked the Regent Palace Hotel with its staff quarters and laundry. The hotel, claimed to have been Europe’s largest when it opened in 1912, had considerable influence on this area and I’ll say more about it shortly.

On the left is the 1,232 seat Piccadilly Theatre, one of the most important in London. When it was built in 1928, its brochure boasted that if all the bricks used in the building were laid in a straight line, they would stretch from London to Paris.

For a short while the theatre became a cinema and premiered the first talking picture in Great Britain (which starred Al Jolson in ‘The Singing Fool’).

More recently, the theatre had an unfortunate mishap when during a performance of Arthur Miller’s play ‘Death of a Salesman’ in 2019, the audience could hear dripping sounds as water began coming through the ceiling. It then partly collapsed, and 1,000 people were evacuated, but fortunately there were no serious casualties.

On your right is something rare these days – a shop specialising in gentlemen’s hats. Whilst it might look like a long-established company, it didn’t start until 2009.

Next to it you can see a window into a corner of the American-owned Whole Foods Market. If you’re a bit of a foodie and haven’t been in a Whole Foods store before then you might care to take a look inside. The entrance is in the street behind, which you reach via the newly constructed Wilder Walk passageway, which is next to it.

In any case it’s worth taking a look into Wilder Walk – you’ll immediately notice the ‘mirrored ceiling’ in the entrance. It’s actually an art installation called ‘Timelines’; lights have been installed within layered glass panels along the sides of the alley, whilst mirrors on the ceiling are great for posing and taking a selfie. Wilder Walk was constructed as part of the redevelopment following the demolition of most of the Regent Palace Hotel, and originally ran through what would have been the hotel’s lobby.

Immediately next to Wilder Passage is the Brasserie Zédel – all that’s visible on street level is a small French-styled pavement café/bar with a few tables outside and even fewer inside. But the big surprise is what you can’t see from the street, for on its lower level there’s a large, reasonably-priced French restaurant, an American cocktail bar and a small and intimate theatre. As I explain below in the information on the Regent Palace, the Brasserie Zédel was created from part of the hotel.

Don’t continue down Sherwood Street but instead take the left fork into Denman Street. Immediately adjacent to the theatre is the Queen’s Head pub (notice the sign on the wall explaining it’s been an independent pub since 1738).

The triangular shaped pub/restaurant that sits between Sherwood Street and Denman Street was once the Devonshire Arms. After it closed, it was converted into a Jamie Oliver’s restaurant, but with the chain’s collapse it became the Coqbull Bar and Restaurant, but this may now have changed again.

Carry on down Denman Street for another 50 yards then turn left into the not too obvious entrance to Ham Yard Village.

Ham Yard has had an interesting history. Its name comes from the Ham tavern (later the Ham and Windmill), which dates back to at least 1739, and probably earlier. It was renamed the Lyric in the early 1890s and rebuilt in its present form in 1906. We’ll pass it as we leave the yard.

Back in the 1920s and 30s Ham Yard was a popular spot for all-night club and music venues but the area was badly damaged by bombing raids during the Second World War and left virtually derelict until the Ham Yard Hotel was built. It opened in 2019.

Since its recent redevelopment, the yard is now surrounded on two sides by the new hotel, with an open area in the middle for drinking and dining al fresco. The newly-planted trees help to give shade and make the open space more pleasant than it would otherwise be. In the centre is an unmissable large gold covered art sculpture by Tony Cragg called ‘Group’ (though personally I can’t see the connection).

The Ham Yard Hotel has 91 bedrooms and suites (costing from around £600 a night to over £2,500). There are 24 residential apartments, a roof top terrace, sunken orangery, four-lane bowling alley, 187-seat theatre, library … so hardly surprising that the place is so expensive.

And something to think about if you stop for an al fresco ‘bite to eat’ … in 1852, the French chef Alexis Soyer, said by some to have been the first ever ‘celebrity chef’, cooked a Christmas dinner here in Ham Yard for around 22,000 (yes, you read that correctly) poor Londoners.

Carry on through Ham Yard – notice the little ‘back entrance’ yard at the rear of it – now just a couple of backdoor emergency exits and refuse bins, but back in the 1960s a doorway here led down a flight of steps into a basement club. It was one of London’s early venues for bands such as the Rolling Stones, The Animals, Chris Farlowe, (remembered for his hit ‘Out of Time’), The Who and many others. Called the Scene Club, it was originally a jazz club but by 1963 it had become one of the top venues for ‘Mods’ (though you have to be of a certain age to recall the Mods and Rockers era).

Turn right now into Great Windmill Street and as you do, notice The Windmill on the opposite corner, which for many years was famous for its ‘nude review shows’. It has closed and reopened several times over the years and following a £10 million refit in 2021 it has opened again. The 350-seat venue now offers nightly cabaret acts, with meals and drinks served at your table. As well as the main auditorium and balcony bar, there’s a basement ‘speakeasy’ called Henderson’s. Laura Henderson was the eccentric pioneer of striptease who ran the Windmill in the 1930s and 40s. She was immortalised by Judi Dench in the 2005 film, ‘Mrs Henderson Presents’, which was later adapted as a stage musical.

The rather dilapidated brick building next to the theatre was once where the 18th century physician and anatomist, William Hunter, built a large house which, besides his living accommodation, included a museum, library and even a theatre where he could give lectures and demonstrations on anatomy. It became known as the Windmill Street School of Anatomy and was used for some years by King’s College for lectures. The building is now part of the stage and dressing rooms of the adjacent Lyric Theatre.

The street’s name (and obviously the theatre’s) was because of a windmill that was situated here, a reminder that this was once farmland. Although it was erected back in the 16th century, much of it remained in place until the late 18th century. As a result of ‘shoddy’ developments in the 17th century a royal proclamation was issued, decreeing that any new building had to be supervised by Sir Christopher Wren, who was at that time the Surveyor of the King’s Works.

Walk to the bottom of Great Windmill Street and on the corner is the St James Tavern, which opened here in 1733 and was rebuilt in 1897. Inside there is a set of four tiled paintings by Doulton’s of Lambeth representing Shakespearean scenes. This was said to have been a stopping point for the gentry arriving into London by horse and carriage, and was patronised by Charles Dickens. He apparently had a favourite chair, where he would “sup the odd glass of port and strong ale.” An infamous character of the past who also enjoyed drinking here was the highwayman Dick Turpin – at least so it’s claimed, but he is alleged to have drunk in all sorts of places, with little evidence to prove it.

You’ve now reached Shaftesbury Avenue, which is famous for its theatres and if you look to the left you can see three in a row – the Lyric, Apollo and Gielgud.

Opposite, on the other side of Shaftesbury Avenue, is what was once the grand Trocadero – you can still see the name. It was the home of the Rainforest Café, and then the Jungle Cave, but that part has recently reopened as Albert’s Schloss London. It offers a bier palace, as well as a ‘cook haus, and bakery with seven days of showtime’. (And its name ‘Albert’ is said to be ‘in honour of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband). Another part of the Trocadero building is now the Zedwell Hotel. It has seven hundred rooms and bearing in mind its position, the prices are often quite reasonable. However, many of the rooms (which they call ‘cocoons’) are very small and without windows, which no doubt affects the price. One of the hotel’s attractions is its enormous rooftop ‘sky garden’, with views across the surrounding area.

The Trocadero building, which was previously home to the London Pavilion, was purchased in 2005 by the billionaire entrepreneur Asif Aziz, (known as ‘Mr West End’, as he now owns an extensive range of properties in central London).

The Trocadero entertainment centre closed in 2011, and Mr Aziz, who has his own charitable foundation that supports a wide range of Muslim activities and organisations, has allocated a small area of the Trocadero building to become an Islamic centre and mosque. Named the Piccadilly Prayer Space, it will be a three-storey place of worship with a mosque.

Turn right into Shaftesbury Avenue. On your left is the London Pavilion, built in 1861 as a music hall – and an odd bit of (useless) information, it is said that this was where the word ‘Jingoism’ came from (which the dictionary describes as ‘extreme patriotism, especially in the form of war-like aggression’). It was an anti-Russian song, sung here during the Russo-Turkish war in 1878, that contained the words “We don’t want to fight, but by jingo if we do, we’ve got the ships, we’ve got the men, we’ve got the money too.”

The Pavilion was rebuilt in 1885 as a theatre, but its uses have changed many times over the years, though its name has remained.

Part of the building is presently the Piccadilly Institute, an enormous nightclub. The building’s owners have expressed an intention to convert most of the Pavilion into a hostel for students, backpackers, and ‘budget explorers’. The conversion is planned for completion in 2025, assuming there are no hitches.

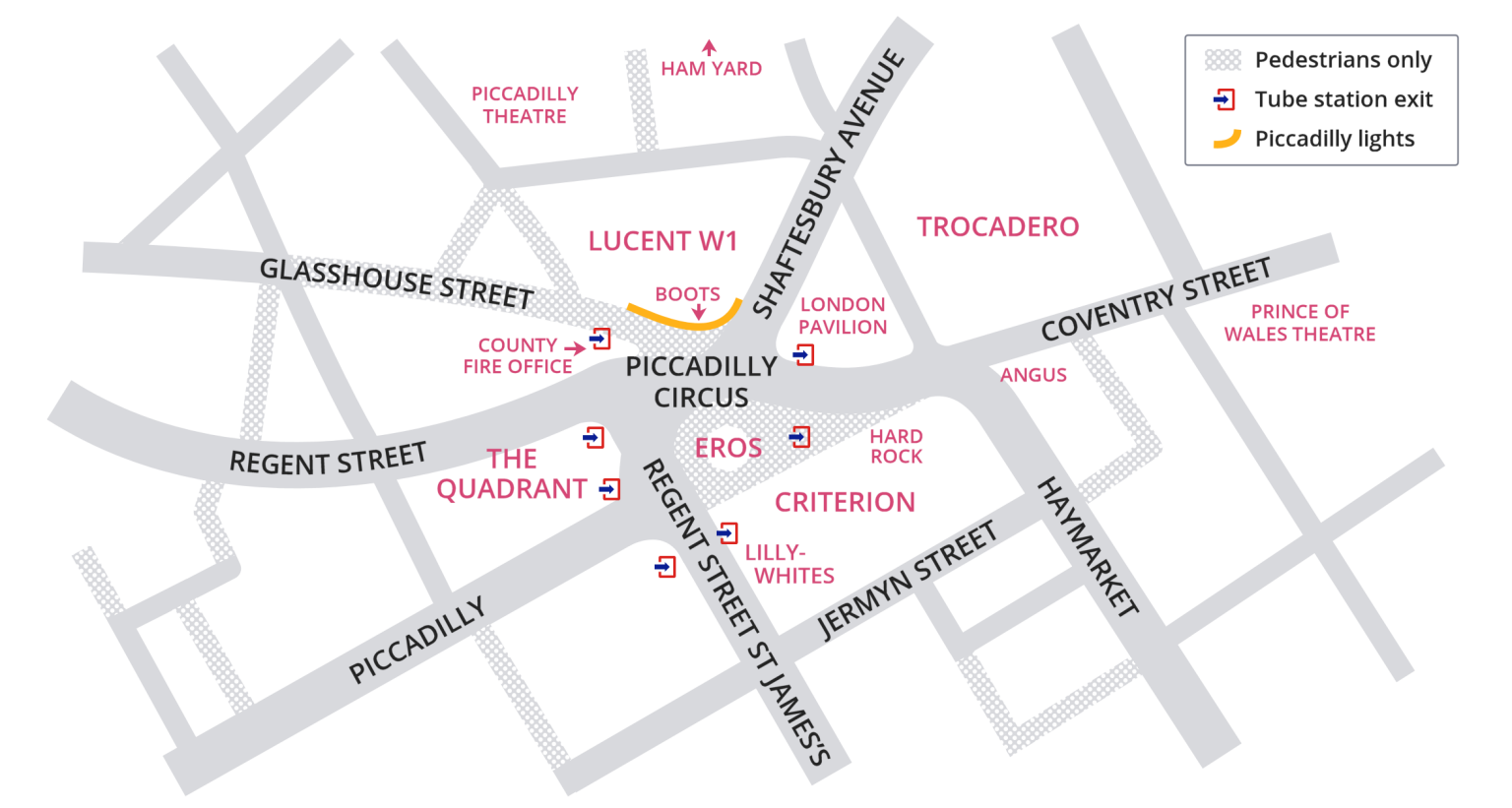

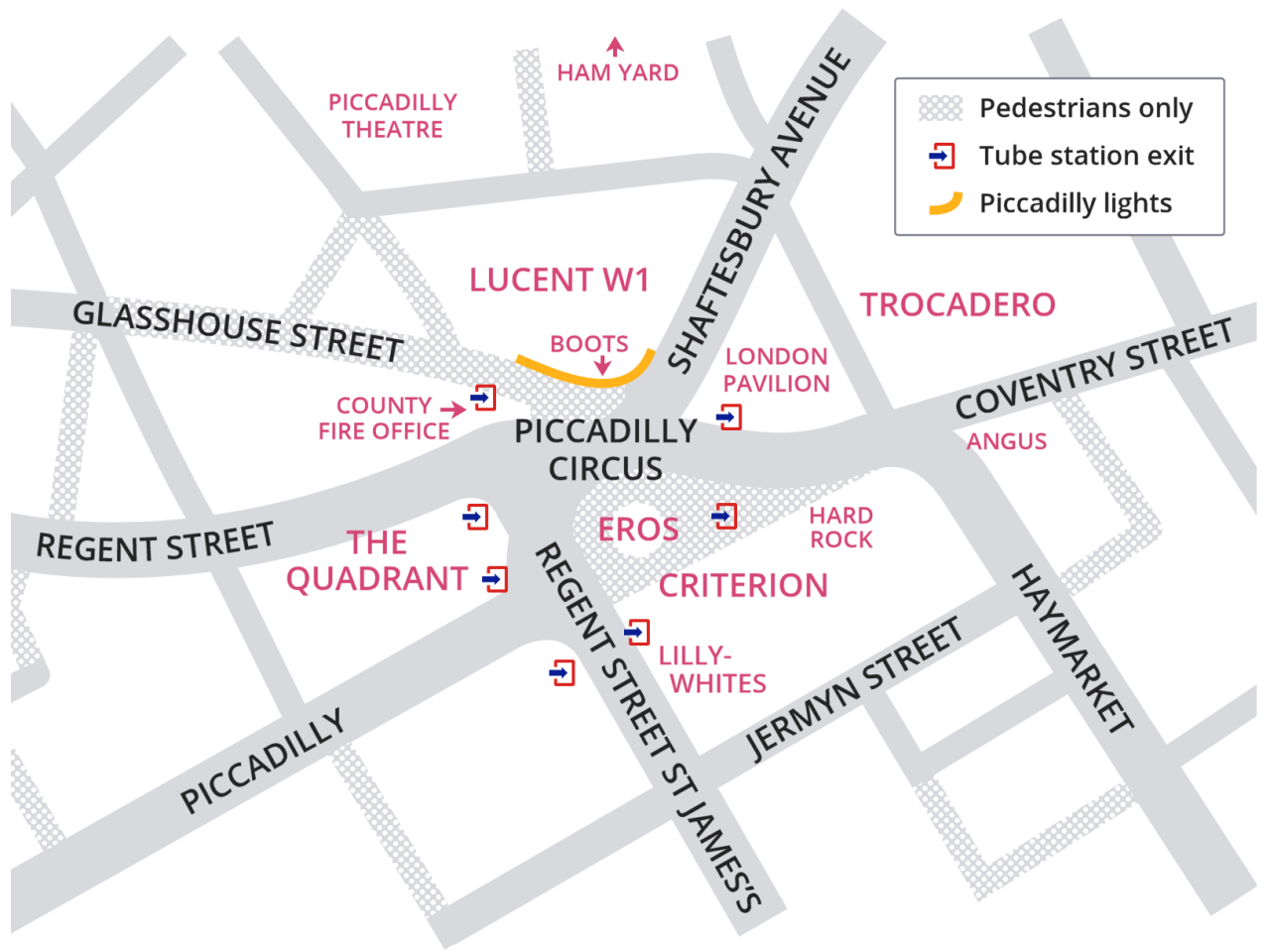

When you reach Piccadilly Circus, walk around to the right for just a few yards. Behind you will be the long-established Boots pharmacy (it opened here in 1925), which used to be open 24 hours a day but now closes at midnight. And high above that are the brightly lit advertising signs for which Piccadilly Circus is famous.

On your right is the curved lower end of Regent Street, with more amazing buildings similar to those we saw at the beginning of the walk. The building closest to you on the right of Regent Street with large windows and iron ‘balcony’ railings, was the headquarters of the County Fire Office, a company founded in 1807, which moved to newly-built premises on this site in 1819. The Alliance Assurance Company acquired the business in 1906 but it kept its separate identity – and its home here, which was rebuilt in 1924–7. The new building was very similar to the original, complete with the covered arcade, which had been a feature of Regent Street when it was built.

Then, looking anti-clockwise, the building on the opposite corner of Regent Street was originally Swan & Edgar. This was once another of London’s premier stores but, like so many, it is long gone. The store had opened here in 1812 and for many years was highly successful. The building was redeveloped in the 1920s, though Swan & Edgar was taken over a few years later by Debenhams, though the name carried on. However, they eventually closed the store in 1982.

Left of the former Swan & Edgar is the start of the world-famous street Piccadilly, which leads through to Hyde Park and Knightsbridge, whilst the road to the left of Piccadilly is Regent Street St James’s (formerly Lower Regent Street).

Across from you, in the middle of Piccadilly Circus is the statue of Eros. The installation was formally called the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain when it was unveiled in 1893 to commemorate the philanthropist, Lord Shaftesbury. Mounted on a bronze, octagonal base, Eros was the first aluminium statue and is Grade I listed.

Behind Eros is the enormous white stone Criterion building, which contains the Lillywhites store, the Criterion Theatre and the Criterion Restaurant which opened here in 1874. There is also now also a Hard Rock café.

The history of the Criterion is fascinating. Built in the French Renaissance style, it opened here in 1874 on the site of an old coaching inn, and as you can see, is enormous – 120,000 square feet to be precise. It contained an exclusive hotel and several restaurants, including the extravagant (and expensive) Criterion. In addition, there were various other dining rooms, a banqueting room, a smoking room, a bar, cigar shop and Masonic room. There was also a Grand Hall that was originally planned to be a ballroom and you can see its enormous dome on the roof. This once contained staff accommodation, which was laid out over two floors, with separate dormitories for barmaids and managers.

You can’t fully appreciate the size of the Criterion building without walking down the side of it, and most of it appears to be empty at the moment. The Criterion’s owners have stated that they will be creating a flagship hotel within the building, with bars, restaurants and nearly 500 rooms. However, though work was expected to have started in 2021, there’s no sign that the redevelopment has yet begun.

For those interested in reading more about this remarkable building, there’s an excellent article from 1879 republished on the Arthur Lloyd website.

The 588-seat Criterion Theatre is unusual in that, with the exception of its box office, it is entirely underground. So much so that when it was built in 1873, fresh air had to be pumped in to prevent the audience being asphyxiated by the toxic fumes from the gas lights that illuminated the theatre.

Next to it is the Criterion Restaurant. Sadly, the original restaurant closed many years ago and the space has since been occupied by a succession of operators of varying quality. Since 2023 it has been a branch of Masala Zone, a mid-market Indian restaurant group. Its predecessor was an Italian restaurant called Granaio and I have left my original photos of the interior at that time below.

Walk back for just a few yards and cross over the bottom of Shaftesbury Avenue and continue ahead into Coventry Street.

The building on your left contained the London Pavilion Theatre. It was originally a music hall and then a cinema, but is now a shopping arcade. Sadly, the ground floor frontage simply contains a number of tourist shops.

On the right, just a few yards further and on the corner of the Haymarket and the Criterion building, is an amazing bronze sculpture called the ‘Four Horses of Helios’. Helios was the Greek god of the sun and the horses were said to have pulled his chariot around the sky. They were installed here in 1992 when the Criterion Theatre was refurbished.

Continue along Coventry Street – on your right is one of London’s longest-standing steak restaurants, the Angus Steakhouse, which opened in the 1950s. Modelled on the popular American steak houses at the time, it offered a menu most English people had not seen before. Nearly seventy years later, little has changed – except the price. Although they generally seem to have had a poor reputation with locals, for many years they were popular with tourists, and I think still are. However, I understand that the 8,000 sq ft three-storey premises are now being offered to rent at a cost of almost £1½ million a year.

Cross over Great Windmill Street, passing a line of touristy shops that form the ground floor of this side of the Trocadero. Cross Rupert Street, which was built in 1676 and named after Prince Rupert of the Rhine, a nephew of Charles l and one of the Royalist commanders during the Civil War.

On the opposite side of the street is the Grade II heritage listed Prince of Wales Theatre, where ‘The Book of Mormon’ has been playing for several years. The theatre opened in 1884, was rebuilt in 1937, and after a further major refurbishment costing £7 million in 2004 opened with Abba’s musical hit ‘Mama Mia’, after it transferred here from the Prince Edward theatre.

Just a few yards further on is Wardour Street, one of Soho’s best-known streets, which we walk through later. But before you continue ahead, pause a moment, first to take in what to me is the ghastliest building to have been erected in this area for many years … the monolithic and exceedingly ugly glass hotel called W London.

Take a look up Wardour Street to see the ‘Chinatown Gate’, This was opened in 2015 by Prince Andrew, and marks the entrance into London’s Chinatown.

The arch is in the style of the Qing dynasty and was made in Beijing and reassembled here. There are three tiers and two pillars with the plaques on either side, which are made from white jade. The decorative panels are embellished with ‘999 gold foil’, (the highest grade available). One of the Chinese texts on the top of the gate translates to read, ‘Peace and Prosperity to Chinatown’.

We explore more of Chinatown shortly, but I’ll just mention that it didn’t really exist here until the 1970s and the area was just a run-down part of Soho.

As soon as you cross Wardour Street notice the Wappenbaum, nicknamed by Londoners the ‘Swiss totem pole’. It has the shields of the coat of arms of each of the 26 Swiss Cantons that make up the Federation of Switzerland. (A canton is their mini-equivalent of a state in the USA). It was a gift from the Swiss people as a token of friendship to mark the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in May 1977.

Immediately after is the magnificent 30-foot high ‘glockenspiel’. It is a giant musical animation clock with 27 bells and a procession of herdsmen and their animals that ‘ascend the alpine meadows’ (actually around the curved wall) at set times during the day. The bells normally chime on weekdays at 1200, 1700, 1800, 2000 and at weekends at 1200, then hourly until 2000.

The short pedestrianised stretch between Wardour Street and Leicester Square was named Swiss Court in 1991, on the occasion of the 700th anniversary of the Swiss Confederation.

On your left you certainly can’t miss M&M’s World – which I’d describe as an emporium of sickly, sticky sweets, bright flashing lights and hordes of mainly pre-pubescent kids. Come here at weekends or in school holidays and the queues outside are just mind-blowing. Opposite is another children’s (and many adults’) favourite – the Lego store.

Cross Leicester Street, but as you do look up to the top of the street where you’ll see an unusual ‘Franco-Flemish Renaissance’ building, with a stepped gabled roof. It’s No. 5 Lisle Street, built in 1897 and designed by Frank Verity, celebrated for his theatre and early cinema architecture. From 1935 until 1989 this was St John’s Hospital for Diseases of the Skin, which when it closed was transferred to St Thomas’ Hospital. The ground floor became a pub – for many years a branch of the Slug & Lettuce chain but more recently the Clubhouse 5 sports bar.

You are now in Leicester Square, with the famous gardens in its centre. Today, the square is the centre of London’s cinema activity, with over 6,000 seats and the UK’s widest screen. Around fifty film premieres take place a year in Leicester Square and on your left, on the northside of the square, is the Empire, which hosts many of these events. The crowds behind crush barriers, stars walking the red carpet and the flashing of hundreds of cameras have been a regular sight for many years.

Leicester Square underwent a huge £15 million renovation as part of the London 2012 Olympic refurbishment.

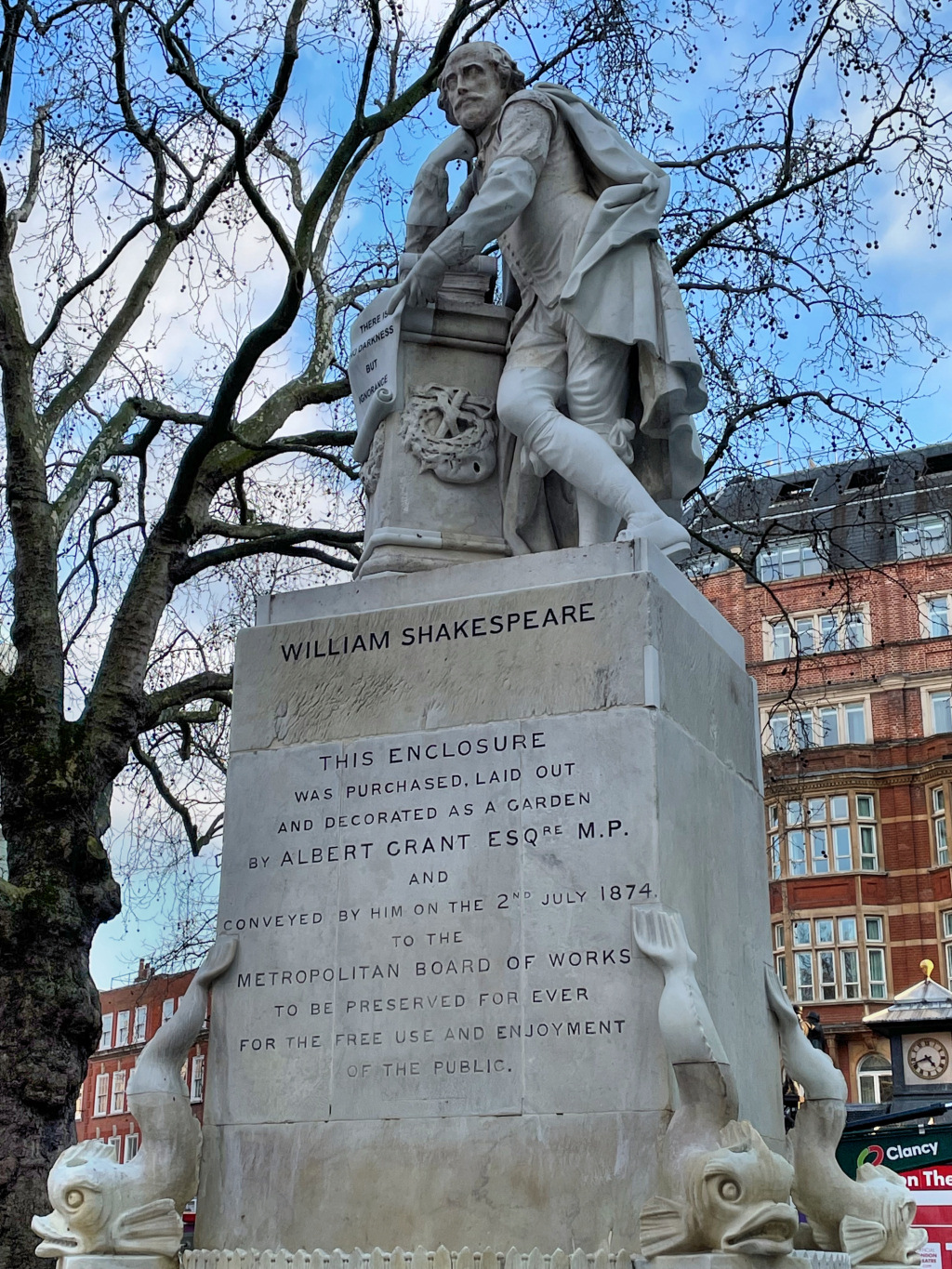

The gardens in the centre of the square were formed as far back as the 17th century, though for many years it was just common land and often very neglected. However, in the 1870s it was purchased by Albert Grant, a businessman and Member of Parliament, who laid it out, created fountains and statues including the one of Shakespeare in the centre, modelled on his statue in Poets Corner in Westminster Abbey. Grant gave it to the council, to be used ‘hereafter as a public space for the free use and enjoyment of the public’.

Beside the entrance there is a statue of Mary Poppins, ‘floating down from the sky with her umbrella’, whilst inside and around the gardens are a number of illustrious characters from the world of cinema carved in bronze. They include Charlie Chaplin, Gene Kelly swinging from a lamp post, Bugs Bunny munching a carrot, Mr Bean, Laurel & Hardy and Harry Potter.

There are entrance gates at each corner, where there used to be busts of notable figures who had lived nearby – Sir Isaac Newton, the scientist; Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy; John Hunter, an early surgeon and the artist William Hogarth. The busts were removed in the 2011–12 revamp of the square, and put into storage by Westminster Council, where they’ve remained ever since, despite being Grade II listed. Apparently, they’d been so badly damaged by the use of corrosive cleaning chemicals in the early 1990s that they would have become “meaningless lumps of rock” if they’d been left outside for much longer.

On the east side of the square is the art deco Odeon Luxe Cinema which opened here in 1937. With a 120-foot-tall tower that displays its name, and black polished granite exterior, it’s certainly impressive. Well-known for its film premieres, it has the largest single screen in Britain and was the first cinema to have the Dolby sound system installed.

We will leave the square from the north side, just along from where we entered, and walk up Leicester Place, (it’s just past the Empire Cinema) but before we do, I suggest you walk a few yards further on to get a better view of the imposing Hippodrome.

The Hippodrome is certainly a spectacular building (now Grade II listed) built using red sandstone, red brick and terracotta. The roof is particularly interesting – an iron skeleton dome supports a group of horse drawn chariots with statues of Roman centurions on either side.

It opened here in 1900 as both a variety theatre and circus, complete with performing animals including elephants and even had an enormous 100,000-gallon water tank for ‘aquatic displays’ including high-diving performances by Annette Kellerman, who was described as ‘The Million Dollar Mermaid’.

Since then, it’s been many things – theatre, night club, disco … After a £40 million renovation and restoration in 2012 it is now primarily an enormous casino, with a number of restaurants and bars. Many of the original quirky features have been retained, and although I’m not a fan of casinos it is quite spectacular inside and worth a visit – particularly the rooftop bar.

Walk back a few yards and turn right up Leicester Place – it’s alongside the Bosporus restaurant – and pass the entrance to the Premier Inn and Ruby Blue bar and club. On the right is the Church of Notre Dame de France, which is quite spectacular inside and well worth a visit if it’s open. It’s a Roman Catholic church that’s particularly popular with French-speaking people, as many of its services are in the French language. (We come to London’s French Protestant church later in the walk.)

Before I discuss the church, I’ll point out that Leicester Place, where you are now standing, was once the marble-floored hall of Leicester House. At the bottom you’d walk out of the front door, and across the forecourt into what was then Leicester Fields – now Leicester Square.

The building that is now the church was built in the early 1800s as Burford’s Panorama, an enormous rotunda which displayed equally enormous 360° panoramic paintings and is the reason for the church’s circular shape. The Panorama was an “early form of visual entertainment for tourists,” something I found fascinating, so I have made a separate reference to it here.

When the Panorama’s lease expired in 1865 it was purchased by a French priest who converted it into a church to serve the needs of the many French people who were living at that time in this area of London. The original entrance was actually in Leicester Square, (where the Bella Italia restaurant now is) but the priest was able to purchase the building in Leicester Place and make the entrance we see today.

Over the entrance is a sculpture of the Virgin Mary, with detailed reliefs showing scenes from the Bible on the doorways. As you enter you are immediately struck by its light and airy interior and its unusual circular shape. It is laid out with rooms and spaces on the side creating a cross-like interior.

Next to the Notre Dame church is the Leicester Square Theatre, one of London’s smallest with just 400 seats. The original theatre was destroyed in the Second World War and rebuilt in 1953, becoming known as the ‘Notre Dame Hall’. Later renamed the Cavern in the Town, 60s pop group the Small Faces were regular performers. Renamed back to the Notre Dame Hall in the 1970s, it hosted bands including the Rolling Stones and The Who. In the 80s it became a punk music venue, with the Sex Pistols and the Clash performing here. In 2001 it was renamed ‘The Venue’, hosting productions such as the world premiere of the Boy George musical ‘Taboo’. Then in 2008 it went through another ‘transformation’ and reopened in 2008 as The Leicester Square Theatre, with American comedienne Joan Rivers making her acting debut with her play ‘Joan Rivers: A Work in Progress by a Life in Progress’. Since then the theatre has regularly featured top comedians – Al Murray, Ruby Wax, Ricky Gervais, Bill Bailey and Frank Skinner, to name but a few.

Next to the theatre is the Prince Charles Cinema, which opened in 1962 as a theatre, with a new office building above. The playhouse proved unprofitable and it became a cinema in 1969. For many years the Prince Charles showed porn movies but it was later successfully reinvented as revival house / repertory cinema. In 2008 it was divided into two smaller cinemas, with the lower screen seating 300 and the upper, housed in what was previously the balcony, just 104. The cinema is popular due to its low prices and distinctive selection of films.

Turn right into Lisle Street. The long row of oriental restaurants leaves you in no doubt that you are now entering Chinatown.

Take the next left alongside the Ku Bar into Newport Place. Ku is one of London’s longest established and still very popular gay bars, attracting big crowds of both locals and tourists. Pass yet more restaurants, some with intriguing hanging displays of ducks (at least I presume they are) in their windows.

Continue through the square and around to the left, passing through the Chinese gateway into the colourful and, no matter what time of day, bustling Gerrard Street. This is the centre of Chinatown.

Gerrard Street was originally spelt Gerard Street, after the military leader Charles Gerard, 1st Earl of Macclesfield, who owned the land and used it for training troops. It was laid out between 1677 and 1685 and later developed into private housing by the physician Nicholas Barbon.

About 30 yards or so on the left is the Loon Fung Supermarket where a plaque on the wall above explains that the poet, literary critic, translator and playwright John Dryden lived in a house that stood on this site during the 17th century. England’s first ever Poet Laureate, he was appointed to the post in 1668.

On the right-hand side is the New Loon Moon Supermarket, occupying what was originally a terraced house built in 1759 on the site of the Turks Head Tavern, founded by Dr Samuel Johnson and Joshua Reynolds in 1704.

Nearly opposite at Leong’s Legend, there are two plaques; one explains that this was the Westminster office of the Penny Post (and later the ‘Two Penny Post’ – they had inflation even in those days), the other that in the basement was Ronnie Scott’s original jazz club – it’s now situated in Frith Street, which we pass shortly.

As you pass the bottom of Macclesfield Street there’s a sculpture on your left called the Two Lions, a gift from the Chinese government that was unveiled by HRH Duke of Gloucester in 1985.

Behind the lions, the incongruously large building is the China Exchange, which looks rather derelict. In 1907 a telephone exchange was built here, which was then rebuilt around 1930 as a post office and telephone exchange. If you ever see ‘GER’ at the beginning of an old London phone number, it was short for ‘Gerrard’ and this was the exchange through which its calls were routed. The building is now a Chinese cultural centre that was established in 2015.

At the end of the street, we turn right into Wardour Street. As you do, notice the O’Neill’s pub that faces you. Its basement (now home to a bookmaker) was previously the Flamingo Club, well known in the 1950s & 60s for jazz and later rhythm & blues acts. Some of the many who performed here back then were Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, John Lee Hooker, John Mayall, Bill Haley, Stevie Wonder, Otis Redding, the Animals, Wilson Pickett – it’s probably easier to list the artists who didn’t play here! The resident house band for several years in the 60s was Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, and they made a live recording of their hit record ‘Night Train’ in the club. And I must point out that this is where, in 1963, the Rolling Stones first performed with the full line-up of Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Bill Wyman, Charlie Watts and Brian Jones.

The club closed in 1967, though a successor called the the Pink Flamingo carried on the tradition for two more years, after which the venue spent several years as the Temple, which was primarily a progressive rock club. Meanwhile, the joint was also jumping at the Whisky a’Gogo upstairs.

Walk to the top and cross the busy Shaftesbury Avenue and continue up on the right-hand side of Wardour Street.

Wardour Street runs north to south through all of Soho, and as a result is one of its busiest streets. It was originally a lane that connected the area around Charing Cross to the ‘way from Uxbridge to London’, which is now Oxford Street.

On the corner is the Sondheim Theatre, which opened in 1907 and was originally called the Queen’s Theatre. The name was changed in recognition of the composer Stephen Sondheim in 2019, following a £13 million refurbishment. It’s currently showing Les Misérables, the world’s longest running musical which, with a break whilst the refurbishment took place, has been playing here since 2004.

We are now in what I call the ‘real’ Soho. The area is packed with interesting streets and sights, and I’ve tried to include as many as possible, without making the walk too long. However, I hope it will give you a good flavour of this distinctive area of London.

![]()

Behind the unusual railings on the right is St Anne’s public park. It was originally the churchyard of St Anne’s, which you can see behind it, though access to the church is now via the adjacent Dean Street. The reason for the churchyard being raised is because it was used for many years as a burial ground – around 60,000 bodies are said to be buried here.

The church was founded here in 1687 and, except for the tower, was virtually destroyed in the Second World War. Left for many years as a bombsite and then car park, it was eventually rebuilt in 1991.

Pass the start of Old Compton Street – which we see more of shortly – and on the next corner on the left is the Round House. Built in 1892, it became the London Skiffle Centre in the 1950s and in 1958 the Blues and Barrel House Club. It later became a blues and skiffle club, and in 2019 it underwent a £1 million restoration and is now the Soho Residence, billed as the West End’s ‘premier bar, club and lounge space’.

A few yards further on, the building on the left displays the words ‘Cinema House’. From 1909 onwards Wardour Street was the centre of the film industry in London and nearly all of the big movie companies had their offices and did much of the post-production work here, some of which continues today. You can still see the evidence with the names of the buildings along this stretch of Wardour Street, such as The Pathé Building, Hammer House, Moving Picture House and Screen House.

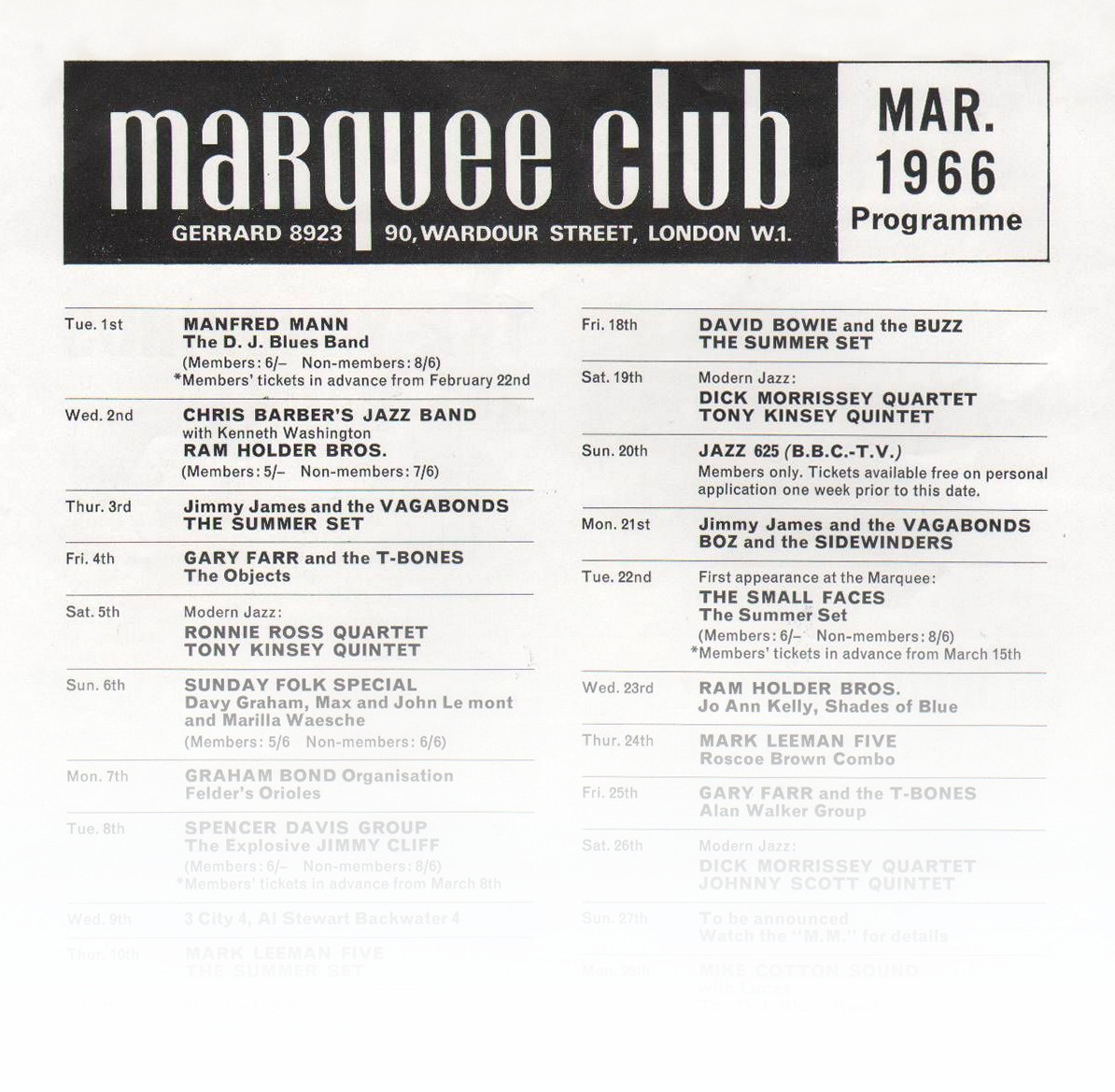

The Marquee Club has been called “the most important venue in the history of rock and pop music.”

We’re going to take the next right into Meard Street. However, if you are interested in (or should I say old enough to remember) 1960s pop music I’ll mention that a hundred yards ahead, at 100 Wardour Street (the building juts out with a very prominent ‘100’ on it), was once the site of the Marquee Club. Well, I say Number 100 … it’s slightly confusing as the actual basement club was next door at number 90, but it extended on the first-floor level to next door at 100 Wardour Street.

It closed in 1988 and was taken over and redeveloped by Sir Terence Conran (of Habitat and goodness only knows what else). Apparently, and I can’t vouch for the truth of this, the effects of the nightly over-amplified bands who played here over the years caused so much damage to the building that its facade eventually had to be demolished and rebuilt. After several reincarnations it is now a bar/restaurant with live music.

Turn into Meard Street – one of my favourite little passages, and one that allows a delightful escape from the hustle and bustle of Soho.

On the right is a row of gorgeous Georgian town houses that are said to be among the best surviving example of original Georgian architecture in London. They were built in the 1720s by John Meard the Younger, who started life as a carpenter and was eventually made the Master of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters.

Early occupants included a harpsichord maker, a vicar (who later became the Bishop of London), an architect, writer, painter, violinist and musical composer – oh, and a woman who was rudely described as “generally a slut, drunkard and occasionally whore and thief.”

Remarkably most are still private homes, though sadly, one has already been turned into a retail shop – quite why planning permission was given for this I fail to understand – I hope no more go this way.

The building on the left is Royalty Mansions, built in 1908 as flats with workrooms for tailors. It was sold in 1978 to the Soho Housing Association and after extensive renovations reopened by the Duke of Edinburgh. There are apparently three apartments per floor, and they each have access to a communal terrace that spans the entire roof of the building. It would appear that their lease expires in 2026, so it will be interesting to see what happens then – no doubt it will be sold to speculators for more apartments for the rich!

To read a little more about Meard Street, see this ‘London Shoes’ blog post, some of which draws on the Survey of London’s characteristically detailed history of the locality.

At the end of Meard Street we’re going to turn right down Dean Street. However, there are several interesting things to see if you look to the left.

First is the delightful pair of Georgian townhouses on the left-hand corner of Meard Street, actually numbers 69 and 70 Dean Street, which were also built by John Meard. The upper floors of these houses were owned by David Tennant, (not the actor, but an aristocrat and socialite) who founded the Gargoyle Club here in 1925. It became an institution, popular with politicians, intellectuals and artists, with members including well-known names such as Noel Coward, Fred Astaire, Virginia Woolf, Graham Greene, Somerset Maugham, Francis Bacon and countless others.

And in case any ‘ageing goths’ are reading this, I’ll mention that after the Gargoyle closed it was used for weekly club-nights of the Batcave, considered to be the ‘birthplace of the Southern English goth subculture’. Regulars at the Batcave included musicians and singers such as Robert Smith of the Cure, Siouxsie Sioux (of the Banshees) and Nick Cave.

Further up the street, on the opposite side, you can see distinctive signs for the Crown and Two Chairmen pub on the corner of Bateman Street and for Quo Vadis, two doors beyond. Until 1736 the pub was simply called the Crown. It is said to have had the ‘Two Chairmen’ added to the name in honour of two sedan chair men who stopped by for a drink after they had dropped off (not literally, I’m sure) Queen Anne, who was having her portrait painted in Sir James Thornhill’s studio opposite. (This must have been an old story by the time of the name change because Anne died in 1714.) The pub was popular with the novelist and illustrator William Makepeace Thackeray and sometime later with two other writers, Graham Greene and George Orwell. The Crown and Two Chairmen was rebuilt in 1929.

The ‘Quo Vadis’ name comes from the Latin, meaning ‘whither goest thou?’ or ‘where are you going?’ It’s a famous restaurant and member’s club, founded in 1926 and known as the ‘Great Dame of Dean Street’. It was originally a brothel and later home to Karl Marx when he lived in central London.

Karl and Jenny Marx had moved to 64 Dean Street (since demolished) in 1850. Jenny later wrote: “In the house of a Jewish lace-dealer we found two rooms where we spent a miserable summer with our four children.” At the end of that year, “we left our small dwelling-place and rented another apartment in the same street … [with] three small rooms.” This was the top-floor flat at 28 Dean Street, above what is now Quo Vadis. Most of the time Marx was here he was struggling financially and it was only with the help of his supporters, including Engels, that the family could survive at all. Sadly, three of their children died whilst they were living in Dean Street. When his wife received an inheritance in 1856 they moved to better accommodation in Kentish Town in northern London.

I’ve only been fortunate enough to eat once in the Quo Vadis, and I have to say it was a delightful meal, with excellent service.

Turn right and head down Dean Street. A short way down on the left, the white stone building at No 43 is another famous club, The Groucho. It was founded in 1985 as a club for those in the publishing world who, tired of ‘stuffy gentleman’s clubs’ wanted somewhere more relaxed to meet. It soon became popular with those in the film, music, arts and media worlds. Wayne Sleep once took Princess Diana here for lunch – and apparently gave her the bill to pay, whilst artist Damien Hirst was said to have put his £20,000 Turner prize money behind the downstairs bar!

Artfarm, which is overseen by Ewan Venters, previously the chief executive of Fortnum & Mason, bought the club for £40 million in August 2022.

At the bottom of Dean Street is Old Compton Street, which we are going to cross over to continue down Dean Street, but before you do, turn to the right for just a few yards to see two more Soho institutions. First is the amazing Algerian Coffee Stores, which dates back to 1887 (and still looks like it). According to a blog post on the shop’s website, the business was established by “an Algerian gentleman called Mr Hassan … then sold in 1928 to a Belgian man called Mr Boerman.” It’s been run by an Anglo-Italian family since 1946.

Although you can purchase a simple latte to take away, the shop specialises in coffees and teas that you’ll brew at home, as well as a wide variety of equipment and accessories. They offer over 80 different coffees and 120 teas.

Next door is the Admiral Duncan, for many years one of Soho’s premier gay pubs. It was here that on 30th April 1999 a nail bomb, planted by a neo-Nazi, exploded and killed three people and injured seventy-nine.

A little further along the street, No. 50 was once the 2i’s Coffee Bar but there’s nothing now to see other than a plaque on the wall. The café opened in 1950 and was said to have played a major role in the development of British skiffle and later rock ’n’ roll. In 1957 the BBC’s ‘Six-Five Special’ was broadcast from here, compered by Tommy Steele; it launched the career of Adam Faith. Other artists to have performed here include Wee Willie Harris, Joe Brown, Screaming Lord Sutch, Jet Harris and Hank Marvin. It closed in 1970.

Cross Old Compton Street and carry down Dean Street.

On your left is the French House, an establishment that has been in existence since at least 1828 and was originally called the York Minster. It is said that there’s been some kind of drinking den on this site since the 16th century. One of its ‘claims to fame’ is that it allegedly sells more Ricard than anywhere else in Britain – and until recently only served beer in half pints. (That changed with Covid, when pints began to be sold, to reduce the number of trips to the bar.) After the fall of France in the Second World War, General de Gaulle, who became the leader of the Free French Forces, moved to London and spent some time in the pub. Here he held meetings with other members, and it is said to be where he also wrote his famous speech ‘Á tous les Français’, aimed at rallying the French people ‘not to give up’.

Take the first left into Romilly Street, continue across Frith Street, then on the left you’ll pass the Kettner’s Townhouse. It was opened here in 1867 by Auguste Kettner, was was chef to Napoleon III.

Kettner’s had an all-day brasserie, cocktail and champagne bar, seven private dining rooms and thirty-three bedrooms and suites. One of the reasons for its past popularity was its fixed price menu and part of Kettner’s appeal was that the food wasn’t expensive. In 2016 the Grade II listed building was bought by the ever-growing Soho House group and became ‘members only’ except for the champagne bar. In 2023 the restaurant reopened to the public. It is apparently no longer a French brasserie, but now offers seasonal British food ‘with a Mediterranean accent’.

Take the next left up Greek Street (the appendix has a brief history of the street), where we immediately see two more Soho institutions. The first is on the corner, the Grade II listed Coach & Horses pub. There’s been a pub here since the early 1700s but the building we see today dates back to 1889, when it became the Coach & Horses. It became a ‘watering hole’ of many artists, writers and Soho personalities including the Beatles, George Melly, Keith Waterhouse, Jeffrey Bernard, Francis Bacon to name a few. Regular readers of the satirical magazine Private Eye might remember this was where its journalists, together with various contributors, would meet every Friday lunchtime for, as they described it, ‘an always very boozy editorial board meeting’. There’s even a Private Eye dining room.

The pub was ‘infamous’ for its host – Norman Balon – who was said to have been the ‘rudest landlord in London’. He had started working here in 1943 and continued for just over sixty years, until his retirement in 2006.

Next door is Maison Bertaux, which was founded here in 1871 by a former Communard* who had fled from Paris during those troubled times and brought with him a collection of recipes. Maison Bertaux was later run by the Vignaud family for several generations until present proprietress Michele Wade bought the shop in 1988. Past customers have included Virginia Woolf, Alexander McQueen and even Karl Marx. It has its own bakery on the upper floors where each day fresh artisan croissants and patisseries are baked.

* A Communard was someone who took part in the revolutionary Commune of Paris around the time of the Franco-Prussian War.

Immediately beyond Maison Bertaux is a relatively new addition to the street – The Wands & Wizard Exploratorium – selling … well, I’ll leave that to your imagination, but its narrow shopfront belies the fact that it stretches over five floors and if you have children, then you may want to look at its excellent website.

And finally on the corner is yet another pub – The Three Greyhounds. The building is around a century old but its mock-Tudor frontage makes it appear much older. There has been a ‘beer house’ here since at least the 1840s, and probably longer. It’s named after the dogs that hunted hares here when Soho was open fields.

Just before you turn left into Old Compton Street and immediately before the Café Boheme, which wraps around the corner, is a rather ordinary looking door. However, ordinary it is not, as this is the entrance to the astonishingly successful private members’ club for top media types and other celebrities – Soho House. There are now over thirty Soho Houses across the world, besides a number of other ‘Soho venues’, including nine Soho Works, catering for those who don’t necessarily have a permanent office or studio, and the Soho Farm that’s set in 100 acres of Cotswold countryside.

But even if you can afford the membership fee, becoming a member is certainly not easy – the current waiting list (though not just for this particular venue) is said to exceed 50,000. Membership criteria are said to prize “creativity above net worth and job titles and moral values above financial success.”

A few years ago when I was working, I was entertained for lunch at the original Soho House here in Greek Street by two BBC commissioning editors, and whilst it actually seemed rather cramped and certainly informal, it was interesting to see several ‘household media personalities’ sitting quietly at the bar enjoying a drink without being bothered by anyone.

Turn left back into Old Compton Street, passing on the right the Prince Edward Theatre, where for a number of years the musical Mamma Mia, based on the songs of Abba, was based. The theatre opened in 1930 – one of four West End theatres that opened that year. Its name has changed several times and, in its time, it has been a cinema as well as a theatre. For anyone interested in finding out more about this theatre, or indeed any other, there’s an illustrated history at the Arthur Lloyd website.

Take the next right up Frith Street, (named after Richard Frith, who was described as a ‘bricklayer’ and who developed Soho Square, which we see shortly). At one time it was said that nearly half the houses in Frith Street – and in some adjoining streets – were lodging houses, where the owners took in paying guests to help pay the rent and cover other costs.

You immediately see two more Soho institutions which almost face each other.

The first, Bar Italia, is on the right and has been here since 1949. It is open from 7am until 3am – so closing for just four hours a day. Not surprisingly, it has always attracted the ‘night owls’ – people leaving the late-night clubs in the area, neighbourhood workers coming off late shifts, and there’s often a couple of police or ambulance workers inside taking a coffee break.

As you’ll see from the blue plaque, No. 22 is also notable as the place where Scottish inventor John Logie Baird gave what is widely regarded as the world’s first public demonstration of television. I’ve written more about this in the appendix, and added some extracts from a newspaper account published two days after the historic event took place.

Opposite on the left is the world-famous Ronnie Scott’s club.

Ronnie Scott was a promising tenor saxophonist who in 1947 ‘blew his savings’ on trip to New York to see for himself what the jazz scene there was all about. He was so impressed by what he saw, heard and experienced there that he eventually opened his own club, at first in Gerrard Street (which we saw earlier in the walk) and later here in Frith Street.

Today it’s one of the best-known jazz clubs in the world and offers a packed schedule – there’s something happening every night at Ronnie Scott’s, which also has an upstairs bar in the style of a 1950s speakeasy. The club draws a mixed crowd, attracting everyone from older jazz fans to tourists looking to enjoy something ‘typically Soho’.

A few doors along on the left is one of my favourite late-night haunts – The Arts Club. It’s nothing special, just a bar and seating/dance area, but the prices are sensible and you normally don’t need to be a member to get in.

Opposite, on the right-hand side, No. 20 Frith Street is of particular importance, though it doesn’t look it today. The first house on this site would probably have been built in the 17th century and it was replaced around 1725. The house was modified in the mid-19th century and it was entirely rebuilt in 1929–30 as the rear wing of what’s now the Prince Edward Theatre, with dressing rooms and a stage door (as the sign above the door indicates, it was then called the ‘Casino Theatre’).

Prior to its theatrical reconstruction the house had an interesting history, and its occupants included the Soho Club for Working Girls, which was established here in 1880 to improve the lives of young women workers. It was home to a cinema in the early 1910s and a nightclub in the late 1920. I’ve written a little more about the building’s past in the appendix.

No. 20’s greatest claim to fame is that Wolfgang Mozart lodged with his father and sister in the house that stood on this site in 1764–5, whilst on a grand tour of Europe. The house was at that time owned by Thomas Williamson, a maker of corsets and stays. Wolfgang celebrated his ninth birthday while he was there (and it was the year he wrote his first symphony, though he had been composing since the age of five).

Time to stop for a cocktail?

Negroni’s has excellent negronis, of course, but also a good selection of other drinks – and, bearing in mind its location, all at sensible prices.

Time to stop for a cocktail?

Negroni’s has excellent negronis, of course, but also a good selection of other drinks – and, bearing in mind its location, all at sensible prices.

Dating from the 1730s, No. 15 is one of the oldest houses in Frith Street, with a rare ‘Gothick-style’ shop front that was inserted in 1816. This Grade II* listed building is now occupied by Negroni’s. I love this little bar/restaurant. It’s narrow, but extends back a fair way. They have an excellent menu that includes some of Italy’s best dishes – I can personally recommend their grilled octopus. (It’s one of those menus where I know I could choose and enjoy any dish.)

Halfway up Frith Street we’re going to take the next right into the short Bateman Street. However, before we do, notice the Dog and Duck pub on the left-hand corner. It was built in 1897 and replaced an earlier pub that had opened here in 1734. The landscape painter John Constable was a regular (he lived in Frith Street). It was a favourite haunt of George Orwell’s in the 1940s and this was where he celebrated Animal Farm being chosen as ‘Book of the Month’ in an American literary magazine. More recently, Madonna has been seen enjoying a drink here – and in May 2023 Prince William and Princess Catherine stopped by. The Dog and Duck is on the Campaign for Real Ale’s national inventory of historic pub interiors.

At the end of Bateman Street we’re going to turn left into Greek Street. But before you do, I’ll first draw your attention to L’Escargot Restaurant, which is just a few yards down to the right at No. 48 and which has been here since 1927. The townhouse it occupies was built in 1741 and was originally the private residence of the Duke of Portland. The restaurant has maintained its elegant style and has paintings on the walls by Andy Warhol, Picasso and Joan Miró.

And another little mention – close by L’Escargot, at number 47, stood the home of Giacomo Casanova, author and adventurer, but best known for his romantic endeavours.

Directly opposite you on the other side of Greek Street there are three interesting houses at 12–14. You can still see their original names – Portland House, Wedgwood Mews and the St James’s and Soho Club, together with a new name that’s been added: Ilona Rose House. The buildings have recently been renovated as part of a massive 300,000 square foot redevelopment that’s been taking place behind them. It extends back as far back as Charing Cross Road and occupies the site of the iconic Foyles Bookshop on Charing Cross Road. (Foyles had been on the site since the 1920s, but fortunately hasn’t closed – just moved to a new site nearby). The redevelopment is being undertaken by Soho Estates, once the property empire of Paul Raymond (see the appendix for some background on him), and subsequently inherited by his granddaughters, India Rose James and Fawn Ilona James – hence the name on the building, which incorporates their middle names.

Raymond’s granddaughters are only in their 30s at the time of writing. (Perhaps it’s hardly surprisingly they’ve now been nicknamed the ‘Queens of Soho’). Their company owns several hundred prime site properties in Soho and this is one of their biggest redevelopments so far.

I understand the doorway in Ilona Rose House will be an additional entrance, not only to the main building, but also to a 2,200 square foot ‘house party venue’ within the building, called the Little Scarlet Door. The company behind the venture already have several “clubhouses with different coloured doors” elsewhere in London.

Portland House, which occupied both 12 and 13, was the largest house in the street. It was so named because in 1698 the first Earl of Portland had been granted the freehold of most of what was then countryside and known as the Soho Fields by the King.

Over the years the building has been occupied by a variety of distinguished individuals and businesses, the most prominent being Josiah Wedgwood, of pottery fame. He used the premises for twenty years from 1774 as his firm’s London warehouses and showrooms, which extended through to Manette Street. This was where he displayed the company’s grandest dinner service, which was made for the Empress Catherine of Russia and which was shown to members of the ‘world’s high fashion’. It was displayed over five rooms on two floors of the house. The house’s late 17th-century carcase remains – but the interior has been entirely altered.

The St James’s and Soho Club was established in 1864 and was one of the earliest working men’s clubs in London. Until recently it was a graphic design and animation studio.

At No. 7 you’ll see an impressive hanging sign for the Pillars of Hercules. The original pub opened here in 1714 (though it was then called ‘The Hercules Pillars’). Hercules was the Greek hero renowned for his courage and strength and Wikipedia has an article explaining where his ‘pillars’ might have been.

Like a few buildings around here, the pub is mentioned in Charles Dickens’s ‘A Tale of Two Cities’ and it has had many literary connections, being popular with writers as diverse as Casanova, Thomas de Quincey, Ian McEwan, Julian Barnes, Martin Amis and Clive James. Indeed, Clive James named his book of literary criticism ‘At the Pillars of Hercules’, saying it was because most of the pieces it contained were either commissioned, written or delivered here. There is also a connection with the poet Francis Thompson, which I’ve put in the appendix.

The Pillars of Hercules closed in 2018. It subsequently reopened as Bar Hercules, then became Jimi Loves Gloria and since June 2022 it’s been a Simmons Bar.

Alongside the Pillars of Hercules is Manette Street, named after a character in ‘A Tale of Two Cities’, which I refer to shortly. It was called Rose Street until 1895. The street has recently been the scene of intensive and messy activity related to the construction of Ilona Rose House.

Number 2, almost at the top of Greek Street, was for many years a very well-known Hungarian Restaurant called the Gay Hussar (though, despite being in Soho, gay it was not). The Hussars were an elite part of the Hungarian army. It became the favoured haunt of many literary figures, such as TS Eliot, as well as with left-wing politicians – Aneurin Bevan, Barbara Castle, Michael Foot, Ian Mikado, Neil Kinnock, Gordon Brown all dined at the restaurant. After 65 years here the restaurant closed in 2018 and was replaced by one called ‘Noble Rot’ (a wine reference).

The last building on the right-hand side is the House of St Barnabas. Now Grade l listed and said to be one of the best-preserved mid-18th century houses in London, it was originally simply called No. 1 Greek Street. Built in the 1740s for Richard Beckford, a wealthy sugar plantation owner, it has since had a varied history – as a private home until 1811, then as the offices of the Westminster Commissioners of Sewers, and from 1862 as the ‘House of Charity’. However, until very recently the house was a private members’ club, although it was run as a social enterprise and non-profit making.

The house provided the inspiration for the imagined lodgings of Dr Manette and his daughter Lucy in Charles Dickens’s ‘A Tale of Two Cities’.

As a result of financial pressures since the Covid epidemic and more recently due to a collapsed ceiling within the building, the directors have been forced to put it into receivership. A great loss to the community.

At the top, Greek Street leads into Soho Square.