Updated: 5 May 2024 |

|

Length: Maximum 1¾ miles |

|

Duration: About 2 hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

King’s Cross and St Pancras walk

INTRODUCTION

“Why King’s Cross?” is a question I was asked when I said this would be my next London Walk.

It’s a good question, as some areas of it wouldn’t have been a pleasant and safe place to walk around until at least the late 1980s, (unless of course you were catching a train, looking for drugs, prostitutes or to commit a mugging!) Indeed, what was once described as being ‘the beating heart of Victorian commerce’ had become one of the largest disused and abandoned industrial sites in Britain.

However, since the extensive modernisation of St Pancras Station to accommodate the Channel Tunnel rail link, the reopening of its famous hotel and the equally extensive modernisation of the adjacent King’s Cross Station, so much has changed.

At its heart is the redevelopment of King’s Cross’s 67-acre area of disused railway yards and derelict industrial buildings behind the station, which has been one of Europe’s most prestigious regeneration schemes.

Almost £3 billion has been spent on the redevelopment, resulting in it becoming London’s newest and most exciting business, educational, residential, retail and nightlife area.

Twenty formerly ‘at risk’ old industrial buildings have been saved and cleverly restored, one of which is now home to the world-famous Central Saint Martins Art and Design College, accommodating five thousand students and staff.

The newly developed Pancras Square, London’s latest ‘tech quarter’ is now the UK home of some of the world’s leading tech companies, including Google and Meta (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc.), as well other enormous corporations such as Sony Music, AstraZeneca, Universal Music, Nike and many others.

There’s an array of excellent new, innovative and fashionable shops, cafes, bars and restaurants.

And we mustn’t overlook that over 40% of the site is designated for public use, including the restored Regent’s Canal and Camley Street Natural Park.

The redevelopment has led to:

Start: St Pancras station |

|

Finish: St Pancras Old Church |

GETTING HERE

By bus

Many buses stop close to St Pancras or King’s Cross stations – too many to list!

By rail

St Pancras (and King’s Cross, which is immediately adjacent) are connected to hundreds of cities and towns.

By tube

Six tube lines – the Hammersmith & City, Circle, Metropolitan, Victoria, Northern and Piccadilly all connect with King’s Cross/St Pancras.

The two stations are only a few hundred yards apart and connected via an underpass.

From the Victoria, Northern and Piccadilly lines, pass through the exit barriers, turn left into the underpass and follow the signs for St Pancras Station and Visitor Centre. At the end of the long passage, go up the steps, turn left in front of the information bureau and the exit into Euston Road is just a few yards further on.

Turn right and then up the inclined roadway that leads to the front of the hotel and station building.

However, the Hammersmith & City, Circle and Metropolitan lines platforms are a little closer to St Pancras, so after passing through the exit barrier turn left into the main passageway and follow the route above.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE AREA

In the space of just 150 years, the area around King’s Cross and St Pancras was transformed from open fields and hamlets into a heavily industrialised and densely populated district of London.

This rapid change began in 1820 with the opening of the Regent’s Canal. This attracted industries, such as the Imperial Gas, Light and Coke Company, who saw the benefit of the cheaper transportation of coal, and built gasworks close to the canal.

The canal was soon followed by the railway, with the line to King’s Cross opening in 1852 and St Pancras in 1868. This meant even cheaper and faster deliveries of coal, encouraging more industry to open here. Just as important was the ability to bring to London bulk quantities of grain, potatoes and other vegetables, fish, etc from areas the line passed through.

This rapid growth meant thousands of workers were needed, along with houses to accommodate them. Many were hurriedly (and poorly) built, and as with the existing houses in the area, they soon became overcrowded, with whole families living in just one room.

This boom continued until the industrial scene began to change. Demand for coal was dropping, goods increasingly being moved by road more than by rail, etc. With gasworks, factories and railway yards closing, this previously thriving industrial area gradually become abandoned until by the mid-1960s it was virtually derelict.

Change happened, and probably the decision to relocate the Eurostar services from Waterloo to St Pancras was the catalyst for the regeneration of the entire area. With the help of government, local authorities and private enterprise, several years of studies and public consultation took place, culminating in a masterplan being created and in 2008. The King’s Cross Central Partnership was then created between the developer Argent, London and Continental Railways and DHL.

The regenerated area has been designated the ‘Knowledge Quarter’ by people in the science and tech businesses. It is now home to a quarter of London’s life science enterprises and a third of its AI companies.

The drugs giant GSK has opened an Artificial Intelligence hub just yards from the Google building, which is also the base for its own ‘Deep Mind’ AI company, and within walking distance to the Alan Turing Institute, the UK’s national centre for data science. In addition, Astra Zeneca have also opened offices here. Another major organisation to have opened recently, indeed next door St Pancras station is the enormous Francis Crick Institute building, which specialises in biomedical research.

These companies say they value the proximity to each other to enable them to share ideas and data as well as being close to Imperial College and the University College of London, both with advanced science laboratories and other research facilities. And as another major plus for companies opening here, it is only a 45-minute train ride from King’s Cross station to Cambridge, whose university is a world leader in science research.

STARTING THE WALK

The walk begins outside the St Pancras Renaissance Hotel, which fronts the station.

To appreciate the hotel’s sweeping frontage, I suggest you start the walk at the front of the hotel building on the busy Euston Road.

The Midland Railway was formed in 1844 and combined three existing companies – Midland County, North Midland and the Birmingham & Derby. Whilst they had the monopoly of rail traffic in the Midlands, they had no direct route of their own to London. Instead, they had to transfer freight and passengers onto the Great Northern Line from Hitchin in Hertfordshire (the southern most part of their network) to King’s Cross. Hence the importance of building the line through to London and a new station at St Pancras.

The company wanted a very prestigious appearance for their new station and a hotel to go with it. They appointed the eminent architect, Sir George Gilbert Scott, and he built it in the magnificent Gothic-revival style that we see today, with its 300ft high clock tower.

Unfortunately, aspects such as bedrooms without private toilets or bathrooms meant that within forty years or so the Midland Grand was no longer so popular and it subsequently became unprofitable. It closed in 1935 and was used as offices for many years. In the mid-1960s there were serious plans by British Rail, who by then owned it, to demolish both the hotel and the station, which had become much less-used, partly due to the increase in rail traffic at the nearby Euston station.

Thanks to a campaign led by the poet and conservationist Sir John Betjeman, together with the Victorian Society and former Bletchley Park codebreaker Jane Fawcett (who earned the nickname of the ‘furious Mrs Fawcett’ for her passionate defence of the building), it was saved, just days before the demolition was due to have taken place, as both hotel and station were given Grade I heritage listings.

However, their condition continued to deteriorate but the decision to relocate the Eurostar terminus from Waterloo to St Pancras in 1996 saw a massive redevelopment take place, both within the station, the hotel and subsequently the entire area that we will be visiting today. You can read more about all of this if you click the button below:

On the left of the building you will see the sign ‘St Pancras Renaissance Hotel’ above the entrance to the hotel with the original date of 1873. Surprisingly, this was once the taxi entrance to the station and hotel.

Optional route: entering the station via the hotel |

Ideally, I suggest you walk in here; however, the hotel’s doormen or security staff are usually either outside or just inside the door to welcome guests, ask if they can help … and deter any ‘undesirables!’ They are very helpful and whilst researching this walk, I asked one of the hotel’s duty managers whether they would allow people doing this walk to have a quick look inside. His advice was that if staff ask whether they could help, politely enquire whether you could have a quick look inside. He said that provided there are only two or three of you then they would normally agree. However, if there are more of you then you should split up.

Once inside, notice the first door on the right with the sign above still saying ‘Booking Office’ – it’s just before the line of check-in desks so after having a look around, leave through this door.

You can see that the architects have created a delightful ‘lobby’ area, which combines the hotel reception with a relaxed seating area where guests can enjoy drinks and light snacks. As I said before, it’s hard to imagine that this is where taxis would once have dropped off passengers and then continued straight ahead; however, as you can see this exit is now cleverly enclosed. I think it’s amazing how well the architects have preserved the original roof and walls.

One of the beautiful features of the original hotel has been retained, which is its grand staircase. It is to the left of this new lobby, and accessible to those staying in the hotel or living in the apartments. The Spice Girls’ famous video for their song ‘Wannabe’ was filmed on and around this impressive staircase. Regarded as a ‘dance-pop song, with influences of hip hop and rap’, it is said to have been the world’s biggest-selling single by any girl group.

Movies with scenes that have been filmed here include Batman Begins, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets and Bridget Jones’s Diary.

Please remember this is a five-star luxury hotel, so don’t wander around taking photos or stay too long.

Besides being a hotel, there are a number of residential apartments within the building, as well as a private members’ club, a gym and spa. An apartment in what was once the hotel’s water tower has three-bedrooms, spans over 6,000 square feet and comes with a private lift. When it was put on the market in 2021 the asking price was £11.5 million.

Leave through the doorway I just mentioned marked ‘Booking Office’ – now a delightful bar area – and continue through along the side of the tastefully designed restaurant and pass through the next door and … well, back to the real world … you are now in the actual station.

If you came through the hotel, then you are standing on what is now the upper level or ‘Grand Terrace’ of the station. Slightly to the left are the Eurostar platforms, which were previously used by the original Midland Railway platforms. The lower level, previously used for storage, is now shops, cafes and the check in for the Eurostar.

It’s hard to appreciate just how much work had to take place here to accommodate the Eurostar. Its 18-carriage trains are considerably longer than the previous Midland Railway’s, so the station and its wonderful roof had to be nearly doubled in length – an incredible job on its own! And beyond the station 19 miles of twin-bore tunnels had to be dug.

Walk past the exterior eating area of the cafe and Carluccio’s restaurant and on your right, you can’t miss the statue of two lovers called ‘The Meeting Place’.

For those who didn’t enter via the hotel

Continue walking towards the clock tower side of the hotel until you reach the large archway public entrance leading directly onto the Grand Terrace of the station.

It is another spectacular way to enter as directly in front of you are the new arrival and departure platforms of the Eurostar trains to the continent. On your right you will see The Betjeman Arms, a tribute to the poet and conservationist Sir John Betjeman (I say more about him shortly).

Whichever entrance you’ve used, pick up the walk at the ‘Meeting Place’ statue.

This 30-foot-high, 20-ton bronze statue is sometimes known as the ‘The Lovers’ and I’ve also heard it called ‘Saying Goodbye’. It’s meant to evoke the romance of rail travel, which I think it does. It was created by British sculptor Paul Day, whose work is known for its unusual approach to perspective. The brief was for it to be romantic, democratic and iconic. However, it wasn’t popular with many other artists, which I explain further below.

Besides the romantic couple, take a closer look at the frieze that runs around the bottom of the statue which depicts scenes of a rich assortment of train passengers, including soldiers returning from war as well as the rail track maintenance workers. I’ve seen it described as a ‘Hogarth of the 21st century’, which I think is a good description.

The platforms behind the glass screen are for Eurostar services, however, they were previously for the original Midland Railway services; these have now been moved to a new area at the rear of the station. You will recall that the front of the hotel and station is considerably above the level of its surroundings, as are these platforms. The reason is that immediately behind the station is the Regent’s Canal. Whereas when they built the adjacent King’s Cross Station, they took the decision to run the lines under the canal, the Midland Railway engineer decided to build over. This avoided trains having to climb a steep gradient as they left the station to cross a bridge, which in the early days when steam engines were not so powerful, would have meant the trains having fewer carriages. And having the hotel and station raised made it look far more impressive than its neighbour, King’s Cross.

This ‘upper level’ is supported by 850 cast iron columns – interestingly the space between them is exactly the width of a beer barrel, to make easier storage of one of the station’s most lucrative of all its goods traffic, the beer coming from Burton-on-Trent in the Midlands. (I explain more about this shortly.)

If you started the walk from inside the hotel, then turn back towards the exit you used – however, if you came in via the public entrance then continue on past the lift, turn right up the left-hand side of the station, passing the doorways marked ‘Booking Office’ (which lead into the St Pancras Hotel).

Ahead you can already see the beginning of the ‘longest champagne bar’ in Europe. Looking down through the glass screens on your right you can see the lower level, which as I’ve just said was previously used for storage, but now shops and cafes.

I’ve already explained why the platforms are much higher than the street outside; the benefit was also that this provided the station with enormous storage vaults, now of course the shops and Eurostar check-in area. However, this below level storage area was invaluable to the profitability of the Midland Railway, as one of their biggest customers were the breweries at Burton-on-Trent, which the line passed through. Every day numerous trains would arrive at St Pancras from Burton carrying barrels of beer. These were then stored down in these ‘vaults’ until they were delivered around London and the surrounding areas.

After just 50 yards on your right, don’t miss the wonderful statue of Sir John Betjeman. He was a conservationist and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1972 until his death in 1984. He is acknowledged as having played the leading role in saving this beautiful building.

I just love the statue! Created by sculptor Martin Jennings and placed here when the station reopened in 2007, it is a public monument to a poet and conservationist who gave so much pleasure to so many. In the years since, the statue has become a celebrated London landmark and regularly a site for poetry readings, weddings and other celebratory events. It depicts Sir Betjeman walking into the new station for the first time. His coat tails are billowing as if buffeted by the wind of a passing express train – although this is of course a terminus! In his hand he holds what is said to be a hemp basket from Billingsgate fish market containing a collection of his favourite books.

He is leaning back, holding onto his hat and looking up in awe at the great architectural spans of the station shed’s roof above him. It is said this was something he often did as it always took his breath away. In the frieze around the bottom of the statue and in the surrounding discs are titles and excerpts from his poetry.

The station hosts the Betjeman Poetry Prize each year. The event aims to foster creativity in young people and is held in conjunction with local schools. It attracts around 3,000 entries from young poets across the country. Past events have included poetry buskers, a poetry workshop and the actual Betjeman Poetry Prize ceremony.

Unless you wish to enjoy a glass of ‘bubbly’ at Searcy’s Champagne Bar, which I mentioned a moment ago, continue on towards the end of the elevated walkway, until the East Midland Railway platform entrances are in front of you, then take the escalator down.

Turn back on yourself and walk towards the entrances to the Thameslink trains. These run from Luton and Bedford beneath London and onwards to Gatwick and Brighton,

Turn right, passing the National Rail ticket and enquiry office on your left and after more cafes and shops, ahead of you is the exit.

Just before the exit on the left are the escalators and lifts that take you up to the new part of the station which has the Southeastern platforms, offering high-speed services to destinations in Kent.

On the left there is a sign for public toilets.

Useless fact

St Pancras is said to be one of only seven stations in England to have multilingual signs, actually only in English and French, like Ashford in Kent, the other main station on the route to the continent. And In case you are interested, which I’m sure you aren’t really, the others with bilingual signs are Southall in west London, where there are signs in Punjabi; Wallsend Metro, which has a sign in Latin, (apparently because of its proximity to the end of the Roman-built Hadrian’s Wall); Hereford with signs in Welsh, whilst Moreton-in-Marsh has signs in Japanese, due to the popularity of the Cotswolds with Japanese tourists.

LEAVING THE STATION

As you leave the station the stock-brick frontage facing you across Pancras Road is part of the German Gymnasium, which I’ll explain about shortly. Cross over to the ‘giant birdcage structure’ – (if you look back at the station you can see the sheer size of the original building, including to the rear the extension built for the Southeastern railway terminus).

You are now in Battle Bridge Place, so named because near here was a bridge over the River Fleet (now buried underground) where it is dubiously said Queen Boadicea (nowadays called Boudica) fought her last battle with the Romans – and lost. Even less credibly, she is alleged to have been buried under platform 9 or 10 in King’s Cross station, which we pass shortly.

But first, the giant birdcage. This 29-foot-high structure is called the ‘IFO’ – The Identified Flying Object (note the lack of ‘Un’ in front!). It was designed in 2011 by Jacques Rival, a French artist and architect and was only meant to be here for two years. However, such was its popularity it has become a semi-permanent exhibit, with the swing that hangs in the middle regularly used – and by all ages!

Before we move on, I’ll say a little more about the German Gymnasium. It’s certainly had a distinctive history.

It was built as a gymnasium in the early 1860s by the German community living in London. And in 1865 it was one of the venues for a series of indoor athletic contests, which were a forerunner to the modern Olympic Games. It was one of the first purpose-built gyms and one of the first athletic clubs in Britain to hold classes for women – and that was back in 1866!

The building has been Grade II listed though part of it had to be demolished for the widening of Pancras Road, as part of the construction of the new St Pancras rail terminal. Not used as a gymnasium since the 1930s, it has since been offices, arts and exhibition space and now a very popular restaurant.

Next we pay a quick visit to King’s Cross station. The station itself is quite simple and built of brick without any facing – nothing like as grand as St Pancras next door – they simply didn’t have the money. In 2005 the huge renovation started, to refurbish the station and add more platforms.

We enter through the doorway on the far left (to the left of the wide stepped entrance that leads down to the Underground lines). This left-hand entrance leads you into the rear of the new part of the station. Pass the new platforms 9 and 10 (beneath which Queen Boadicea is improbably said to have been buried).

Immediately ahead of you (usually hidden behind a waiting crowd) is Platform 9¾ – made famous of course by the Harry Potter books. There’s nearly always a queue of people waiting to have their photo taken pushing the luggage trolley through the wall and onto the fictitious platform. (There is a Harry Potter gift shop here as well).

Ahead you can see what an amazing job the architects have done in creating this new spacious extension on the outside of what was the original exterior wall of the station. The new spectacular glass and steel ‘half semi-circular roof’ opened in 2012. The designers described it as a ‘striking new ‘diagrid’ shell structure … supported by perimeter tree columns and a central funnel structure.’ This means it is structurally independent of the Grade I listed building and is the largest single-span structure in Europe. In total, around £500 million was said to have been spent on the renovations.

And if you’d like to see the original King’s Cross station, which has also been renovated, then continue almost to the far end, and just before the exit, turn left. You can walk along the passageway to the far side of the station to the original platforms 1 and 2. From here you can see the wonderful arched roof, which when the station opened was said to be the biggest such arch in the world and modelled on the riding stables of the Czars of Moscow.

The legendary Flying Scotsman train used to depart from here every morning at 10am. One of the responsibilities of the station master was to be there in person to see it off, wearing his formal suit and top hat to do so.

On a more serious note, sadly the station has had two tragic events in recent years – an IRA bomb in 1973 and then the terrible fire in the tube station beneath that was started by a cigarette being dropped under one of the escalators. Many people died and many more seriously injured.

(You can step outside the station if you’d like to see the renovated exterior and the attractive area outside that’s often used for markets, etc.)

Leave the station the same way you came in and walk back to the Identified Flying Object and walk to the right of the German Gymnasium.

You’ll see the paths split here – whilst the right-hand fork (King’s Boulevard) goes up past Platform G, the huge new Google building on your right, we take the narrower left path, passing the lovely oak tree that was grown in a nursery in Hamburg and brought here by lorry and ferry.

The tree is currently around 50 feet tall but will continue to grow and, for those who are interested in trees, it is a Quercus palustris – otherwise known as a pin oak. When it arrived, it weighed over 11 tons and it took a 55-ton crane and six men to put it in position. It is said to be one of over 400 mature trees to be planted within the new King’s Cross development.

Although we don’t walk past the Google building, a few words about it:

We continue to the left of the tall building fronted by eight latticed iron pillars with the Vinoteca bar and restaurant at ground level.

To the left of Granger & Co. is the Stanley Buildings. This is all that is left of the five buildings that once accommodated over a hundred of the families of men and women who were working here. They were built in the 1860s by the Industrial Dwelling Company and were some of the earliest examples of concrete being used in building construction. (I explain a little more about the company in the Tower Bridge to Wapping Walk.)

You are now in Pancras Square, though to me it’s not exactly a square – more of a triangle – and carry on walking ahead.

One of the delights of Pancras Square are the flowers, plants and mini hedges. The water features are particularly attractive; a series of stepped terraces using Caithness stone that are particularly attractive at night when illuminated with white lights.

With two major rail stations on the doorstep, offering excellent transport links around the country, as well as into Europe, and with a vast array of leisure and entertainment facilities on their doorstep, a number of companies have chosen to build new offices here. Besides the enormous Google building we’ve just seen, there’s another, smaller one on the left. As you walk up, between the cafes, you will see its entrance.

And, surprisingly for office buildings in London, you can actually go inside – at least far enough in to appreciate the amazing interior, which I’ve included a picture of here:

Continue walking up the right-hand side, passing the new offices of Universal Music. A ten-storey block, it was built on the site of the largest gasholder of the 23 that were once at King’s Cross. As a result, the architects have used exposed weathering steel, giving it a passing nod to the gasholder. As part of the redevelopment of the area, the gasholder was taken down and erected on a new site, which we see later in the walk.

The building has spectacular roof gardens and ponds, with two restaurants and a large reception area on the ground floor. On the right, is the Havas building (one of the world’s largest communication groups).

At the top, cross over the road known as Goods Yard and carry on over the recently constructed bridge. It was named the Espérance Bridge by the children of the nearby King’s Cross Academy primary school, who had learnt that it was close to what was once the ‘Esperance Club’ and the ‘Maison Espérance’.

Espérance means ‘Hope’ in French, which is what the children – both then and I’m sure now – still want. It was a ‘pioneering social project that had been set up in the 1890s to help relieve poverty in the area by providing education for girls and to teach them skills to assist their employment opportunities’. It was also a dressmaking co-operative that helped the extremely poor women who were working in the clothing industry in the area.

There’s been a bridge here across the Regent’s Canal since the canal was constructed in the 1820s. That bridge was replaced by a stronger bridge to allow trains to bring coal from the mainline through to coal works closer to King’s Cross station. This second bridge was taken down in the 1920s when rail freight began to decline and the one you see today has only recently replaced it.

The Regent’s Canal runs for nine miles from Paddington in west London, where it has links to the Grand Union Canal, and ends in the east at Limehouse, on the River Thames. It enabled freight, such as coal, to be brought by ship up the Thames, offloaded at Limehouse and transferred onto barges, and brought along the canal to King’s Cross.

The Regent’s Canal runs for nine miles from Paddington in west London, where it has links to the Grand Union Canal, and ends in the east at Limehouse, on the River Thames. It enabled freight, such as coal, to be brought by ship up the Thames, offloaded at Limehouse and transferred onto barges, and brought along the canal to King’s Cross.

As you cross over the canal on your left you can see what were the brick-built Fish and Coal Buildings, which have now been restored. These were the offices of the clerks responsible for keeping tally of the goods arriving here. (On the other side of the building you can just make out the wording ‘Coal office’). The building was seriously damaged by fire and rebuilt and is now the head office of Tom Dixon, the designer, known for his innovative lighting and furniture. You get a better view of it once you’ve crossed the bridge.

On your right are a series of canal-side steps which, in the summer at least, are covered with artificial grass making it an attractive and popular place to sit, particularly on warm summer afternoons and evenings. Various outdoor music and other performances take place here, and a large screen is erected for regular cinema events. These include the showing of major sporting events, such as the Wimbledon tennis championships. Drinks are often served here as well. I will just say that it is sometimes humorously known by locals as the King’s Cross Riviera!

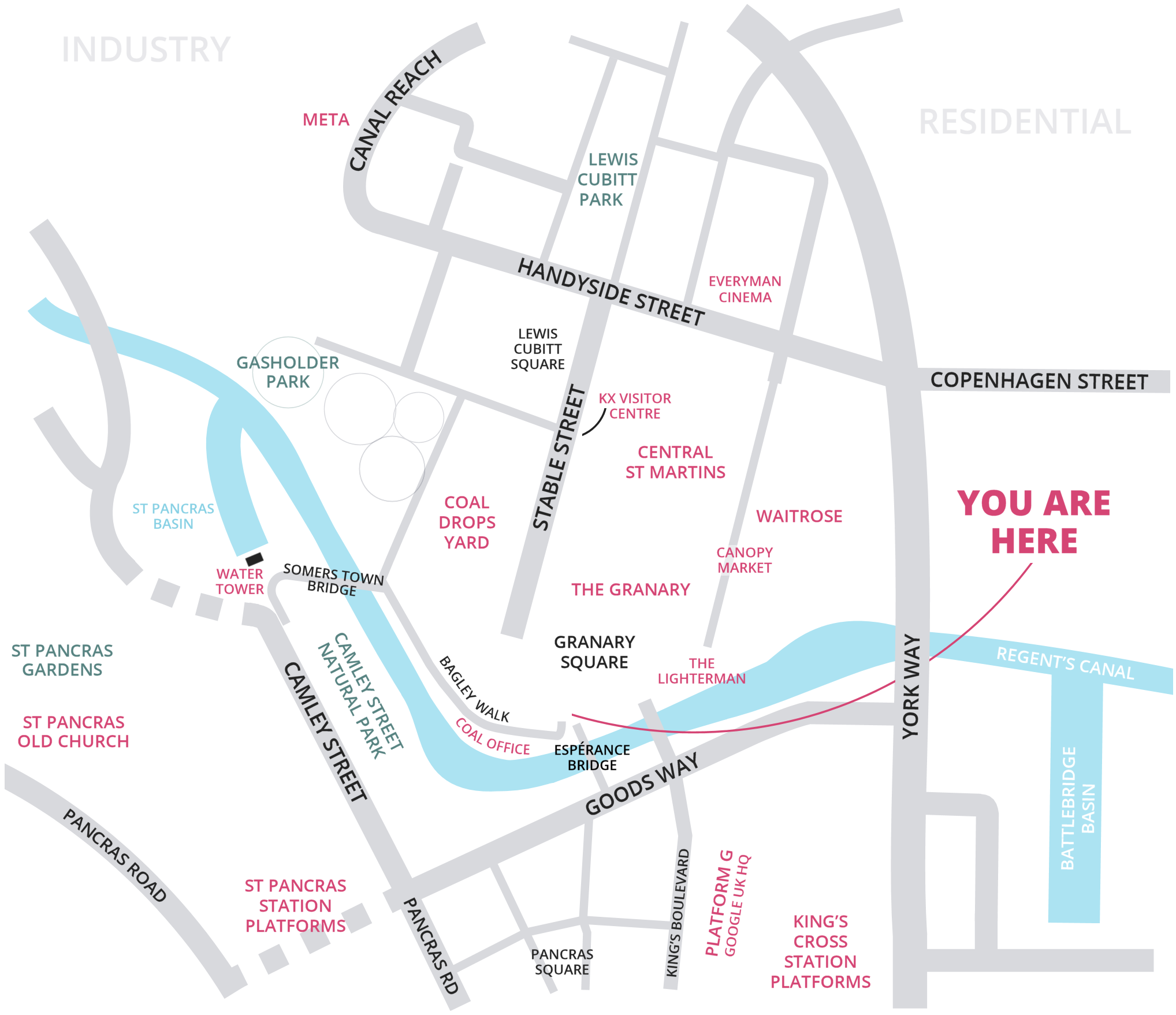

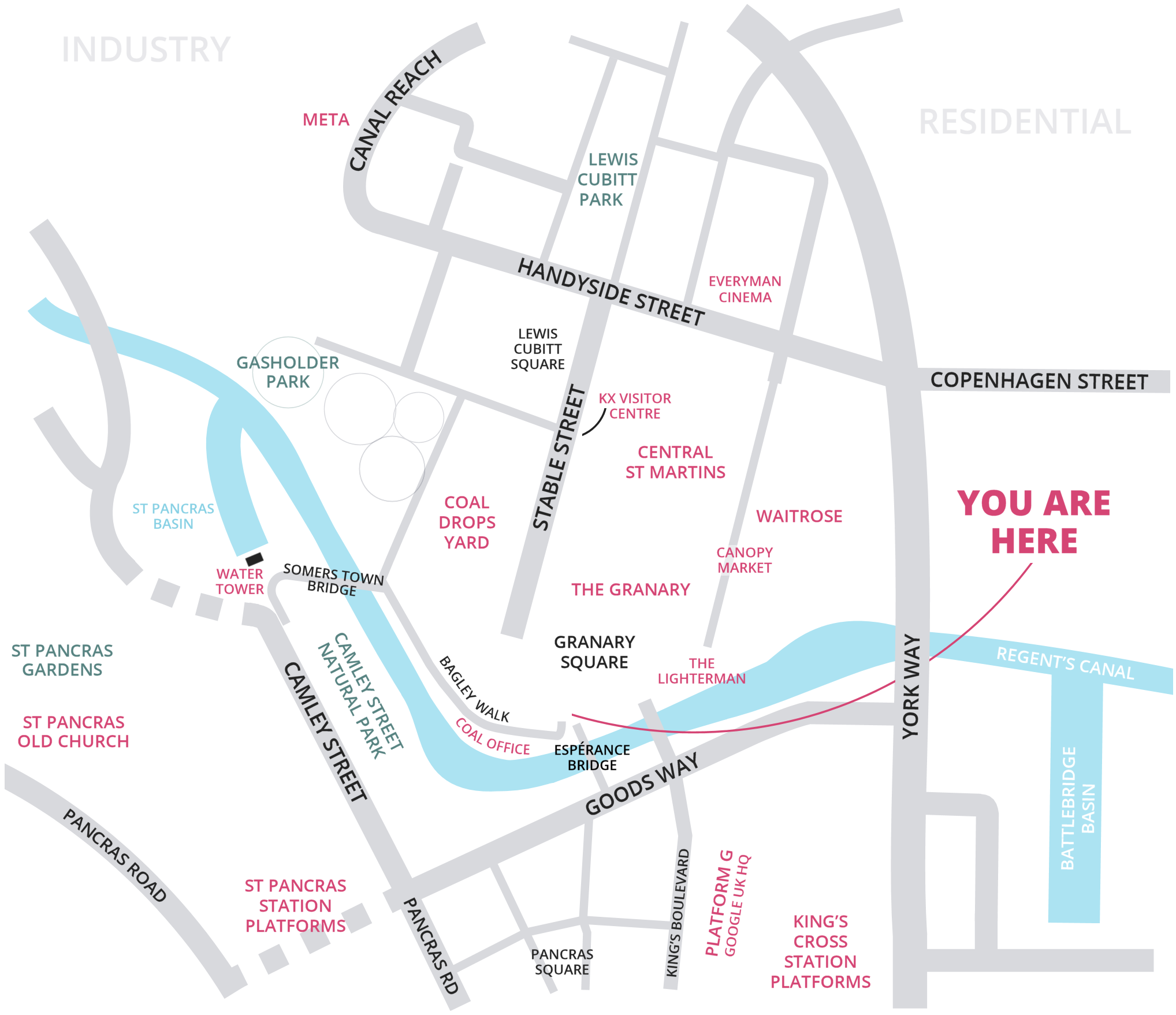

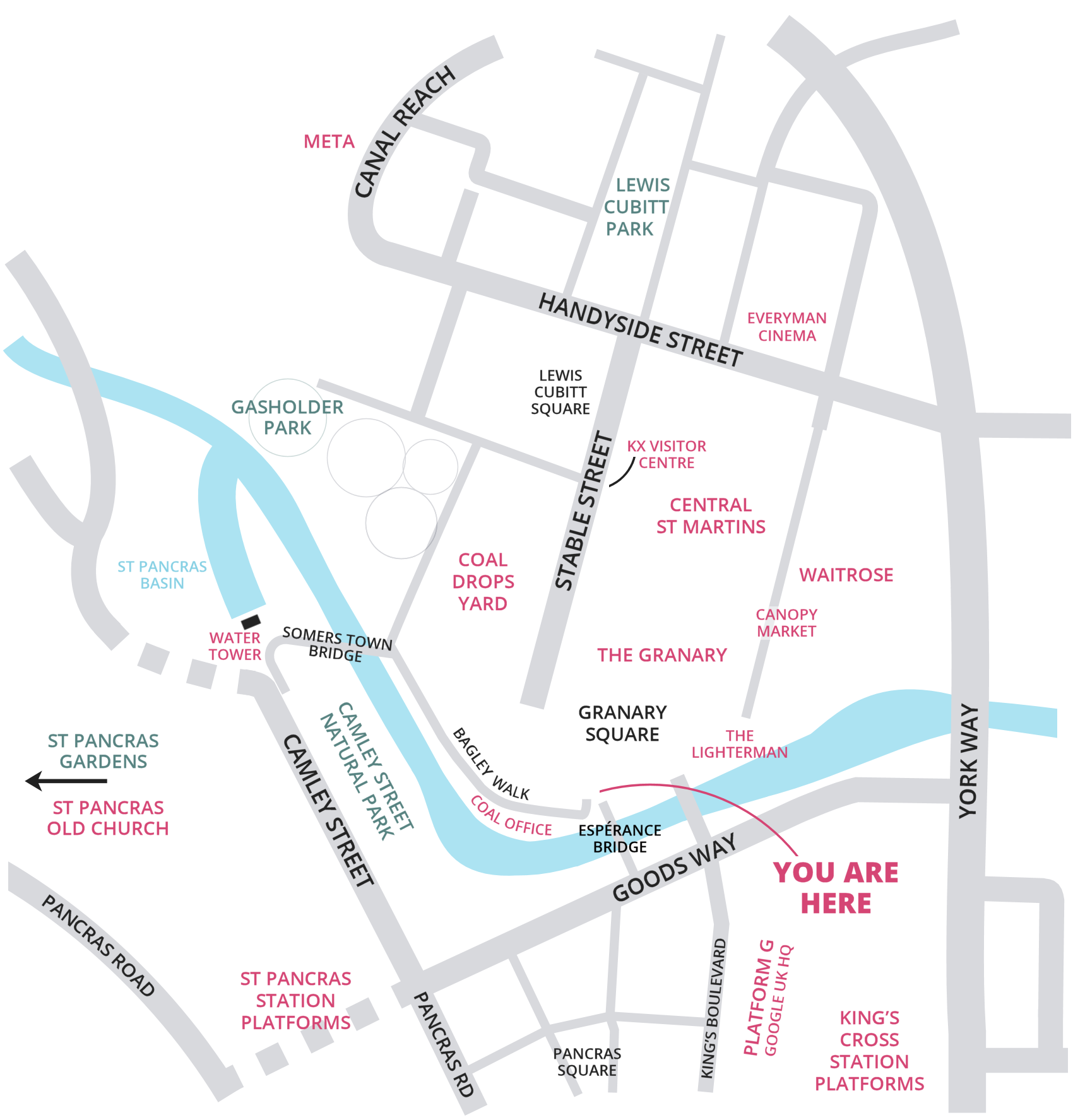

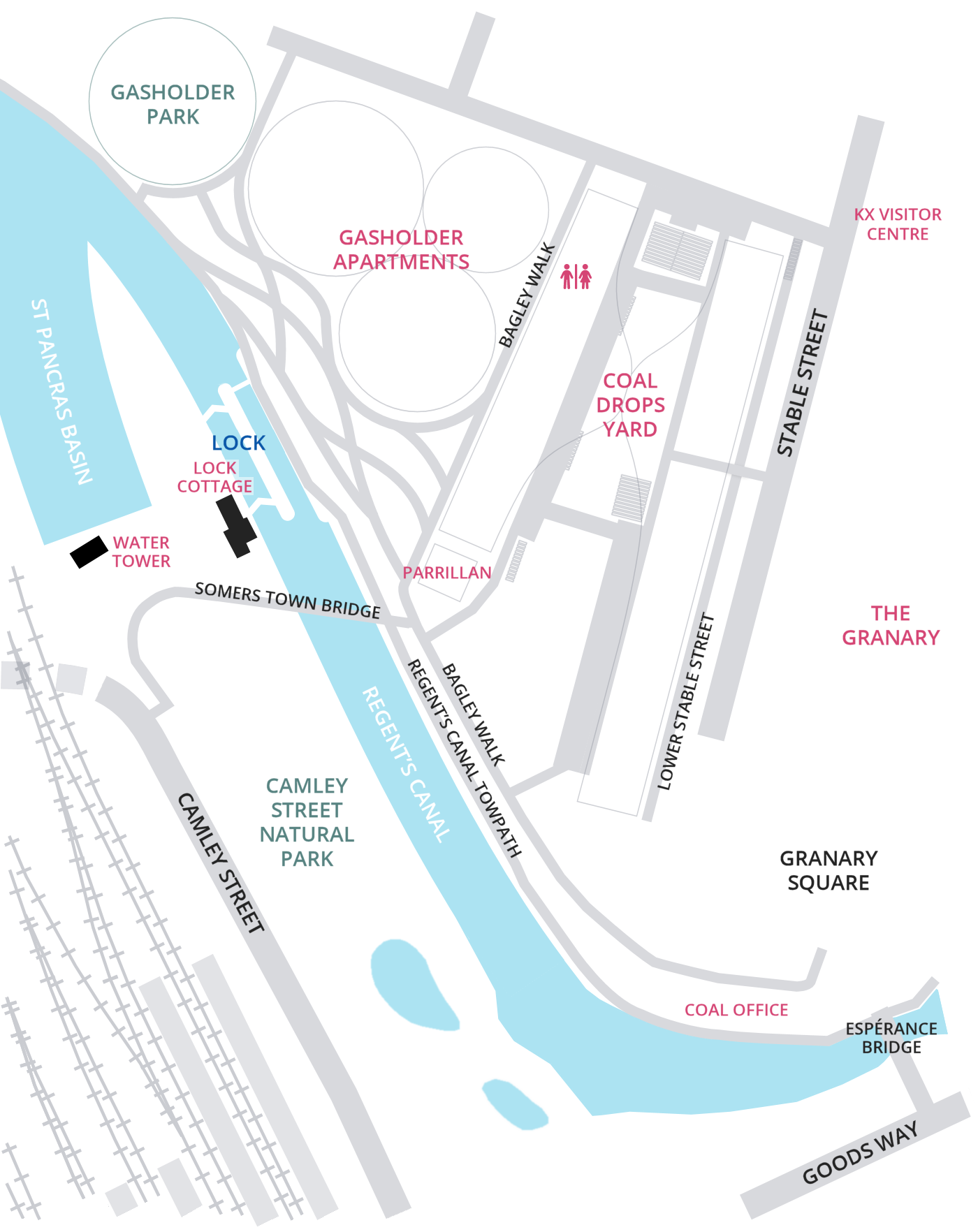

Before you go any further, I suggest you pause for a moment to get your bearings.

On your left the inclined road leads down to the newly redeveloped Coal Drops Yard – you can see the building from here and the gasholders, both of which we visit shortly.

Ahead is Granary Square, so named because the large brick building on the opposite side was built as a granary in 1852. Here trains from Lincolnshire and East Anglia would bring wheat from farms to be stored before being sold to London’s bakers. More on this in a moment. Another major crop brought here was potatoes, which had their own storage warehouses.

The square was originally a water-filled canal basin. Barges would enter from the canal and pass into the Granary building where they would be directly loaded with goods from trains. (Two lines came into the rear of the building) – an excellent example of how efficient the distribution of goods here had become).

We’re going to head across to the Granary, which has the popular Caravan restaurant on the left-hand side of the front, passing the lovely fountains, a popular highlight of the square. There are four banks of fountains, containing over 1,000 jets, all with individual pumps and coloured lights. It can be great fun to watch children running in and out of the jets, not knowing which ones would suddenly spring into life, whilst others would almost disappear.

Apparently, the fountains were also linked to an ‘app’ called the ‘Granary Squirt’ which allowed those who downloaded on to their smartphone to play a real-time version of the computer game ‘Snake’. However, the app is not currently in use.

Walk to the right of the Granary, passing the The Lighterman bar and restaurant – extremely popular in the summer, especially as it overlooks the canal. (A lighterman was somebody who would unload ships or barges – thus making it lighter – and transferring it to a small barge or onto the quayside. Many were employed at this very busy canal interchange.)

As you walk between the Granary and the Lighterman notice the railway track still set in the ground and the ‘turntable’ that allowed individual railway wagons to be rotated.

Walk down the side of the Granary and on your left is the wide entrance into the building, which we turn into next.

But first I’ll just mention the building on the right. This was called Regeneration House and was once the offices of the Goods Yard and responsible for the moving of freight across the yards. Badly damaged by bombing in the Second World War, it was rebuilt by the London Regeneration Consortium and is now the home of the Art Fund, the charity responsible for fundraising to help museums and galleries to purchase works of art. It is also the home of Queer Britain’s national LGBTQ museum.

The area ahead under the restored steel and glass canopy was the Eastern Transit Shed (the Western Shed was on the other side). In addition, whilst King’s Cross station was still being built, it was turned into a temporary station to enable Queen Victoria to travel by train to Scotland. After the main station had opened, it was where fish, potatoes and other perishable foodstuff would arrive by train and be unloaded. Until the canopy roof was installed the amount of vegetables that could be handled was limited, and it helped protect both the food and the men who were unloading. Perishable produce such as vegetables had to reach Covent Garden in the early hours, and the hours before dawn were always very busy here. (To give you an idea of the size of the vegetable trade, around 100,000 tons of potatoes would arrive at King’s Cross each year!)

Special fish trains also ran here as early as 1852 from as far north as Sunderland and Edinburgh. A major staple were herrings, either fresh, salted or smoked. Later, express goods trains, which ran at passenger train speeds, came from Aberdeen, Hull and Grimsby, which were then the major east coast fishing ports. These would arrive at King’s Cross throughout the night and be transported as quickly as possible to the Billingsgate Fish Market. (Fish was sold here on Sundays when Billingsgate was closed).

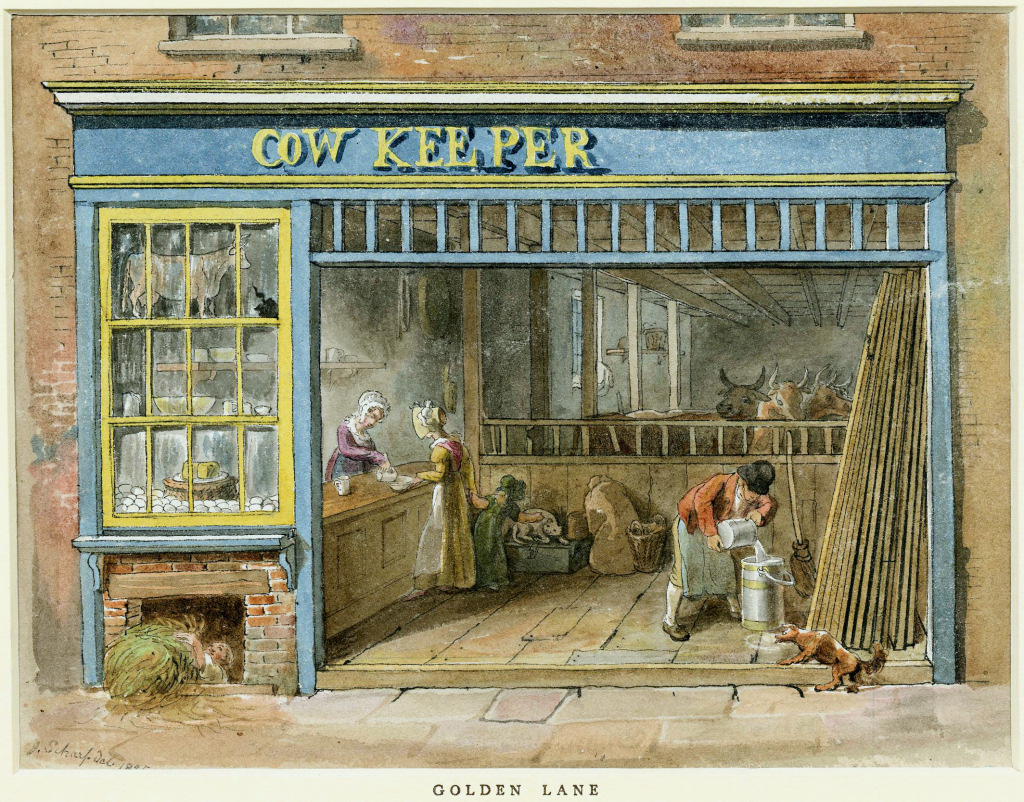

Milk also became an important commodity, as I explain here:

The area is now used for markets, particularly the Canopy Market on Sundays, when a wide range of stalls are set up here, several selling excellent and interesting food.

The building across on the right inside the covered area was the Midlands Goods Shed and now a Waitrose supermarket. I like the way in which they have managed to retain just a little of the evidence of the building’s previous use, such as the few faded painted signs on the walls. Waitrose has an excellent café area and toilets, should you be in need of either.

Turn now into the Granary through the entrance on the side and into the long ‘corridor’.

The Granary was built by Lewis Cubitt in 1852, who also built King’s Cross station, to enable grain, primarily from Lincolnshire and East Anglia, to be stored. It would be brought here by train and the sacks would either be stored on the floors above or put into the waiting adjacent canal barges or horse-drawn wagons.

If it was stored here, then it would be raised up by hydraulic power, then when it was needed, a system of chutes enabled it to be moved down through the floors and into the waiting delivery carts below. Around 60,000 sacks, holding 5,000 tons of grain which would make some nine million loaves of bread, could be stored here, to be sold to London’s bakers.

The building has been cleverly renovated and restructured to be the home of the Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design.

Walk through this long indoor passageway that runs from one end of the building to the other. The conversion from grain store to college has been cleverly carried out, with several restored original features – notice the faded painted numbers on the walls beside what would have been the canals or roads that ran into and through the building from the basin outside.

Part way along on the left there’s an exhibition space where students’ work is sometimes on display, whilst on the right you can see the student’s entrance into the university. You need a pass to enter, but you can see a central ‘street’, with overhead walkways. The lecture theatres, workshops and student communal areas are on either side. This clever design allows a freedom of movement that makes it easier for students of the various departments to mix and share ideas.

Leave the building through the exit at the far end – in front of you is the newly renovated Coal Drops Yard, which we visit shortly. Turn right along Stable Street. Until the era of motorised lorries, huge numbers of horses were used to move goods around on carts, and the street is named after one of the places where the stables were built. At one time the Great Northern Railway was one of the largest owners of horses in Britain and by the beginning of the 20th century they were said to have over 1,500. The company had a reputation for both the quality and well-being of the horses, which even had their own infirmary to deal with injuries or illnesses.

A few doors along is the Dishoom Indian restaurant where, as with their other restaurants in London, there is invariably a queue to get in. The restaurant was originally one of the stables.

Next is the KX Visitor Centre and Recruitment Office – they have an amazing model of the entire King’s Cross development site, which you can look in to see. They also have information leaflets on the area, as well as postcards and posters like the ones below.

When you reach the end, or front, of the Coal Drops building turn left. There are two separate flights of steps. The first, a narrow flight takes you down to where there were more stables, which now house several little shops and cafes.

We’re going to walk down the second, wide flight of steps into the Coal Drops Yard.

Before you do though, I’ll just mention that the wide-open space to your right is Lewis Cubitt Square, leading into Lewis Cubitt Park. Cubitt was the builder of King’s Cross station and much of the original industrial area you are in. From here you also get another idea of the size of this brownfield redevelopment area.

The office building on the left side of Lewis Cubitt Square is the second, and smaller, of the two new Meta buildings within the King’s Cross development. (For those who are not familiar with the name ‘Meta’, it is the holding company of Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and other divisions.) With nine floors and a wraparound terrace on the fifth floor, it provides just under 200,000 square feet of office space.

Also, you can see the enormous, redeveloped gasholders, which I’ll explain more about shortly.

The section in front of you, which links the two sides of the long brick and cast-iron sheds, is known as the ‘kissing roofs’. They are called that as they only just seem to touch. They were designed by Thomas Heatherwick, the architect appointed for the three-year £100 million redevelopment of the yard. He brought in 80,000 slate tiles from the same Welsh quarry as used on the 1850 original covered roof. Indeed, as you’ll see when you walk through the yard, wherever possible use has been made of the original brick and iron work to try and keep as much of the original heritage as possible. Within the bridge space is a 20,000 square foot Samsung ‘experience space’, displaying products such as mobile phones, watches, etc.

When the King’s Cross redevelopment plan was being put together, it was decided not to demolish but to renovate this yard and convert it into the design-led retail and nightlife area we see today. (There were other similar Coal Drops Yards – for example one was on the site of Camley Street Natural Park, which we pass shortly, but this is the only one that has been kept).

Among the shops within the yard are a couple that enable students from the adjacent Saint Martins Art and Design College to have affordable retail outlets to test whether their work has commercial potential. There are also several commendable bars and restaurants, as well as excellent toilets.

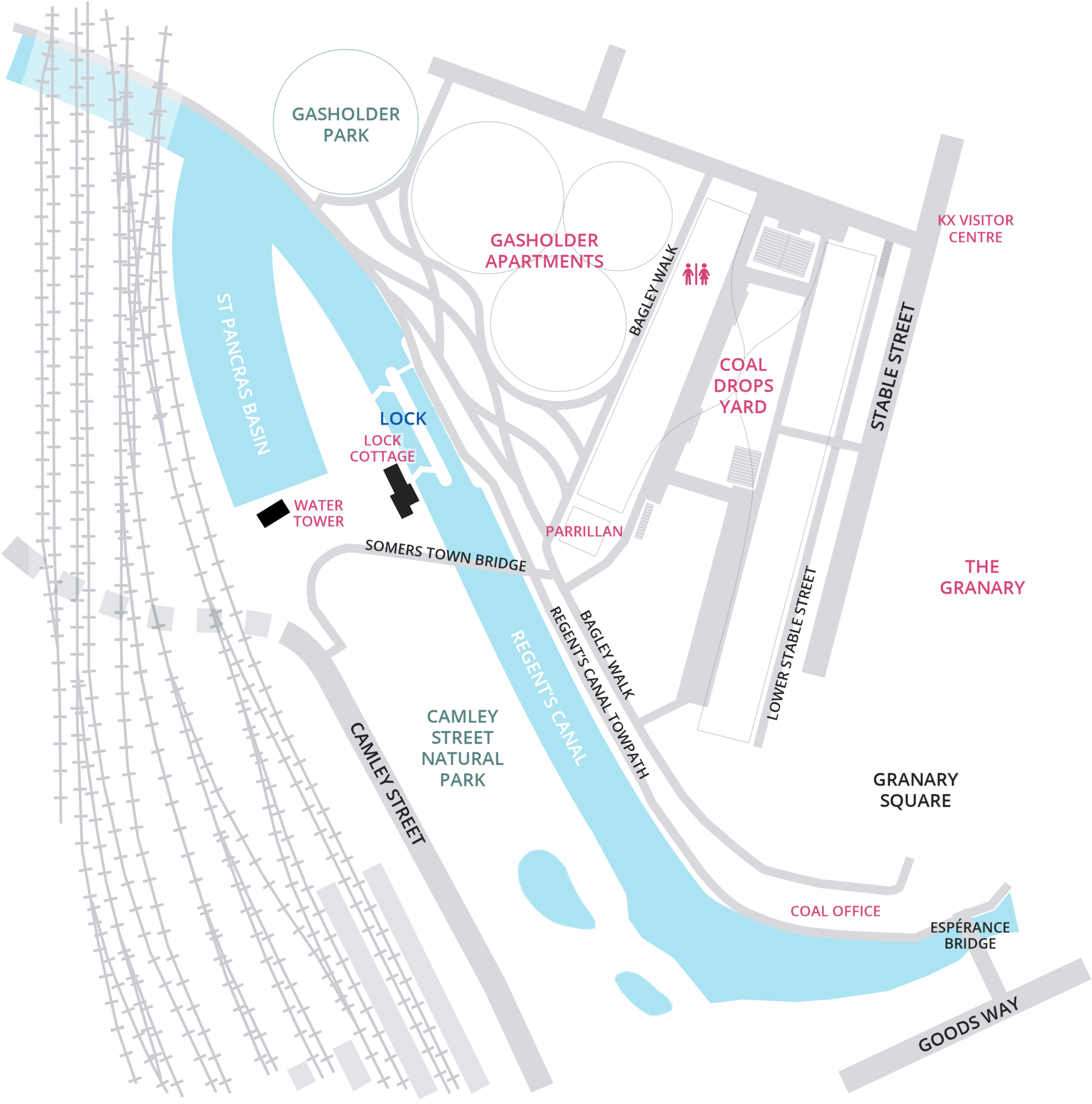

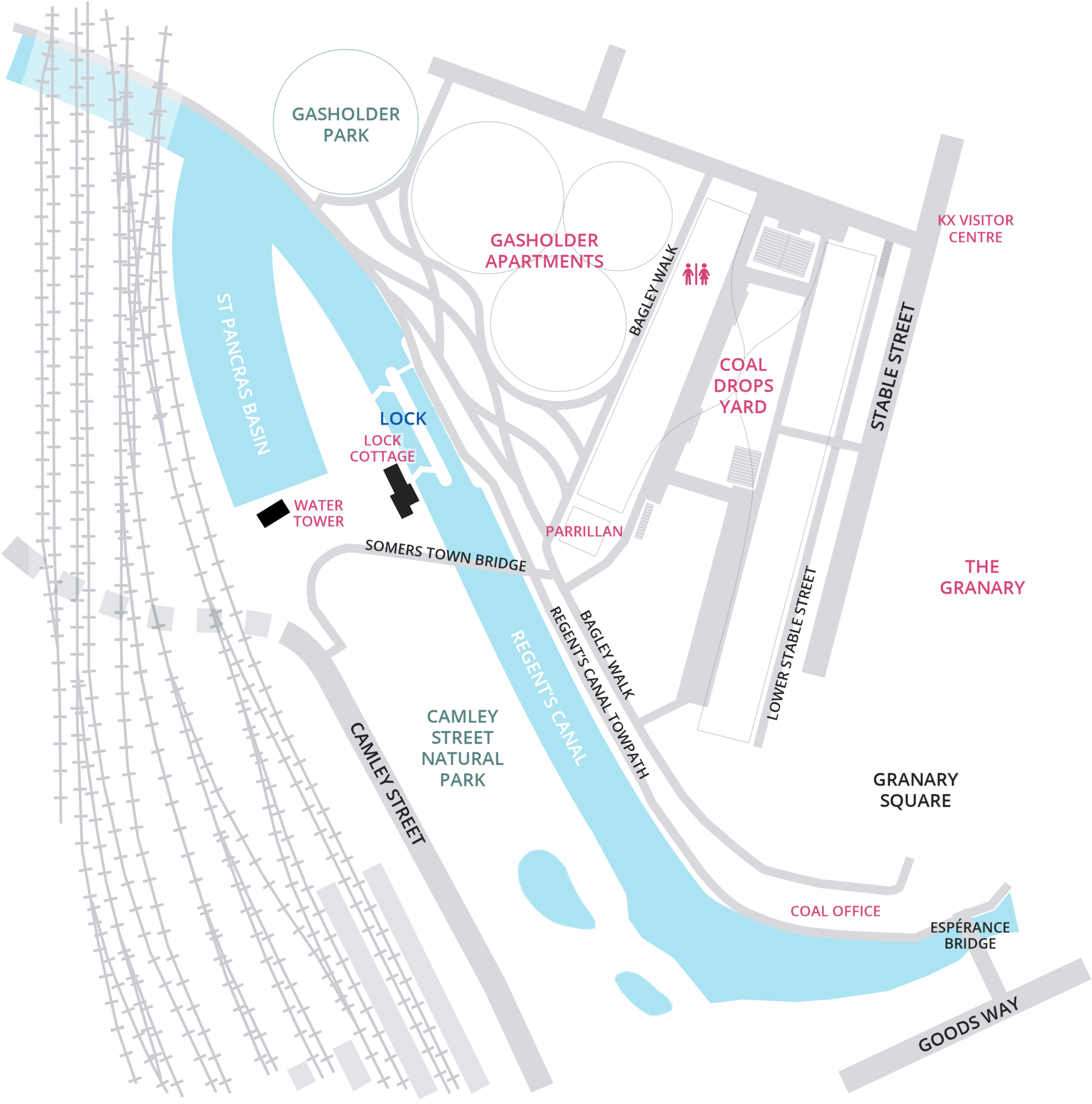

On the right side at the far end where the yard widens, you’ll see a double-arched opening between two shops. Go through here and you’re on the bank of the Regent’s Canal. (In this, and the other archways that are now shops, was The Cross nightclub, which I’ve mentioned above). On the other side of the canal you can see Camley Street Natural Park, which we see again shortly. Within the double-arches there are time-line history plaques.

Walk back just a few yards into the yard and take the iron steps on the left to the upper level. Then turn back on yourself, walk past the attractive alfresco Parrillan Spanish Restaurant. (Parilla means ‘grill’ in Spanish and you can grill your order of meat, seafood and vegetables on mini charcoal grills with white-hot charcoal coals that are brought to your table. I’ve walked past so many times, but still never at a time when I’m ready to eat, but it’s high on my to-do list.)

The walk will continue ahead over the bridge that crosses the Regent’s Canal – but first I suggest you turn to the right and walk down the path to take a closer look at Gasholder Park.

Gasholder Park is another of the amazing architectural and engineering feats that have made the renovation of King’s Cross so successful.

There were originally 23 gasholders at King’s Cross, with all but four being demolished over time. The four that were ‘saved’ were Number 8, which was the largest of all the gasholders at King’s Cross, along with Numbers 10, 11 and 12. The regeneration projects’ architects and developers decided to make a feature of them and in 2011 they were carefully dismantled and taken to the specialist Shepley engineering company in Yorkshire for restoration.

They were returned here two years later and, cleverly, three were put back as the ‘Siamese triplets’ as they share a common spine. They are now home to 145 attractive apartments, surrounded by 123 iron columns. And notice the different heights of each of the buildings. This was done to emphasise how the gas ‘envelopes’ would rise and fall with the amount of gas being stored. I would love to stay in one of these apartments, especially one with a south-facing view.

Next to them is the original iron guide frame of Gasholder No. 8, which previously stood where Pancras Square has been built today, which we walked through earlier – hard to imagine today! Before it was decommissioned in 2000, Number 8 was able to hold just over one million cubic feet of gas. It now encloses the Gasholder Park, a public space where music and other events take place. A particular feature is the mirrored pergola surrounding the central garden. Attached to each of the iron columns are the guide rails for the ‘roller carriages’ (which are still in place) upon which the canopy would rise or fall, depending on the amount of gas being stored.

And I will just add that when the gasholders were dismantled, they discovered that each column was bolted together from the inside – and as an adult could never have managed to have fitted inside, it was clear that small children had been sent up inside them to tighten the bolts.

If you visit after dark, then you are supposed to be able to watch a ‘solar eclipse’ every 20 minutes. (I say ‘supposed’, as I personally have never seen it). It was described in the Architect Magazine as a ‘lighting sleight-of-hand’. LED uplights along the canopy’s perimeter dim sequentially, simulating the moon moving across the face of the sun, creating a dynamic spectacle for both the residents of the surrounding King’s Cross redevelopment and children from a nearby school’. So now you know!

Just a little further on from Gasholder Park, on the north-west edge of the King’s Cross development, is the bigger of the two new Meta office buildings and the conglomerate’s largest tech hub outside of the US.

It cost around £200 million (though it apparently also cost Meta £149 million to break its clause to leave their previous building near Euston – even though they had never actually moved in) and was opened in 2022 by Their Royal Highnesses the Prince of Wales and Duchess of Cornwall, now of course the King and Queen Consort. With 620,000 square feet of workspace, it provides 5,000 workstations. As with the new Google building, it has huge roof gardens for staff to relax.

Turn back and cross over the canal on the new Somers Town Bridge. On your right is St Pancras Lock, which was built with two locks side by side due to the amount of barge traffic that used it. However, only one is now working.

The lock-keeper’s cottage has been preserved and is Grade II listed. It was originally a ‘pumping house’ which helped maintain the levels of water in the canal but was converted into living accommodation for the lockkeeper in 1926. More recently, it was sold at auction for £800,000 and is now rented living accommodation. I recently saw a double room advertised at £1,100 a month – what a lovely place to live!

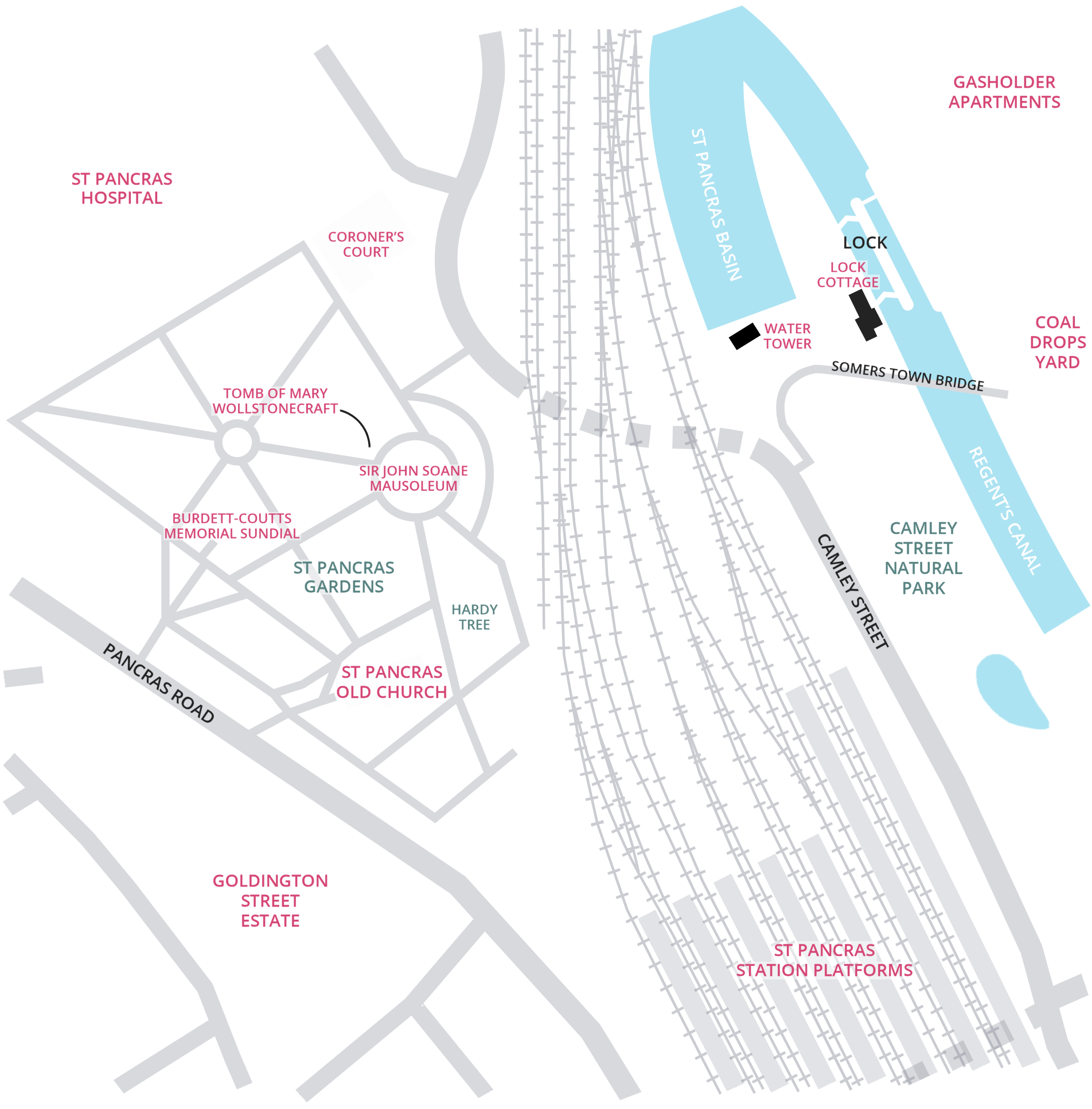

Camley Street Natural Park

As the path curves around, you’ll see the distinctive brick-built ‘tower’ above you on the right. This is the St Pancras Waterpoint, where the ever-thirsty steam locomotives filled with water from a cast-iron tank inside that held 2,400 cubic feet of water. The ornate design was the work of the team of Sir George Gilbert Scott, the architect responsible for the hotel and frontage of St Pancras station.

On your left is the two-acre Camley Street Natural Park. It was set up in 1985 by the London Wildlife Trust and Camden Council and is on the site of another of the Coal Drops. It has an excellent, partly-covered outdoor cafe that has sandwiches, cakes, etc. And there are well-maintained toilets. The entrance is on the left at the end of the path. For more information, see their website.

Cross over Camley Street, walk through the tunnel under the railway and, after 100 yards or so, you’ll see the entrance into the gardens and burial ground of St Pancras Old Church.

As you enter the gardens the old building immediately on your right is the Coroner’s Office, which opened in 1886 and was the first to be custom built. It is now a Grade II listed building. And I’ll just mention that beneath was a large pit that was dug to hold the bodies of 7,000 people formerly buried in the church yard.

Behind it is the Coroner’s Court and the Public Mortuary.

It is interesting to walk around the garden, which until 1854 had been the burial place of thousands of people. However, to build the Midland Railway’s St Pancras station they needed some of the land occupied by the churchyard. I explain more about this when we reach the Hardy Tree.

Take the main pathway to the left. The gardens have plenty of old tombs, but one that is rather special is the large mausoleum behind the railings on your right. This is the grave of John Soane, the great architect who was responsible for the Bank of England’s building in the City. He initially designed this mausoleum for his wife but, when he died some twenty years later in 1837, he joined her here. It incorporates Soane’s favourite emblems of Creativity and Eternity – the pineapple and the serpent swallowing its own tail. It is one of only two Grade I listed monuments in London. (The other is the tomb of Karl Marx in Highgate Cemetery).

And if you think it reminds you of a telephone box then you’re correct. The mausoleum gave Sir Giles Scott, (the grandson of Sir Gilbert Scott, who built the St Pancras Hotel), the idea for his design in 1922 of what is now the iconic GPO telephone box, a hundred years later.

Continue following the main path around to the left towards the church, and you’ll see where the Hardy Tree once stood. Sadly, it collapsed in a storm on Boxing Day in 2022. And although the tree is no longer standing (at the time of writing it is lying close by), the gravestones that surrounded it are still in in their original place. However, when I last visited, bushes around the gravestones were making it difficult to see them.

There is so much to explain about this little site that I’ve put more here:

Turn right immediately opposite the Hardy Tree site and walk down the side of the church. However, you may wish to have a walk around the garden, so if you do, I’ll explain a little more about what you can see here.

Firstly, in the middle is a blue water fountain with five pillars. It no longer functions, but it was presented by a former churchwarden, William Thornton, in 1877.

The most prominent of all the memorials in the churchyard, just behind the fountain, is the Angela Burdett–Coutts Memorial to Lost Graves that was erected in 1877,

It isn’t a memorial to her; instead, she paid for this ornate gothic sundial to commemorate the many graves and gravestones that were lost when part of the churchyard was cleared for the Midland Railway. The sides of the memorial contain the names of many notable figures and their professions, including immigrants fleeing France at the time of the Revolution. (Angela herself is buried in Westminster Abbey).

An amazingly generous and thoughtful lady, and friend of Charles Dickens, I first heard about her when I was writing my East End Sunday markets walk and read about the profound influence she had on the lives of many of the poorest people in the area, so if anybody else is interested I have written more about her here:

Despite Henry VIII’s Reformation, Elizabeth I allowed the Catholic Latin Mass to continue here in St Pancras Church, and no doubt as a result, several of London’s well-known Roman Catholics as well as French and German immigrants were buried in the graveyard. They include Johann Christian Bach, the youngest son of Johann Sebastian Bach and known as the ‘English Bach’. He became the music master to Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, and was buried here in 1787. His name is on the Burdett-Coutts Memorial.

Two other prominent Catholics buried here include William Franklin (the illegitimate son of Benjamin Franklin), and the writer and founding feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft. In 1792 Mary wrote ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Woman’ as well as novels, a history of the French Revolution and a children’s book.

Also buried here, but as with Mary Wollstonecraft his grave was destroyed during the building of the new railway line, was the Chevalier d’Eon, at the time a well-known French diplomat and spy. He had become ‘famous’ because whilst working as a spy he dressed in women’s clothes but became reluctant to relinquish them afterwards. I write just a little more about him here:

Finally, Charles Dickens had a number of connections with the churchyard.

Charles Dickens’s connections with St Pancras churchyard

Charles Dickens knew the area well as he spent much of his childhood living nearby whilst his parents were in the debtor’s prison. So, if you have read A Tale of Two Cities then this is the graveyard where Jerry Cruncher brought his son, Jerry Junior to undertake some ‘fishing’, The word ‘fishing’ was a euphemism for body snatching; the body snatchers would come and dig up recently buried bodies and sell them to the early medical schools for students to dissect.

This is also the area where Dickens’s school master, Mr ML Williams Jones, lived and was buried, who was his inspiration for Mr Creakle in ‘David Copperfield’. Living in a nearby street, and apparently attending his school, he said of him, “… he is by far the most ignorant man I have ever had the pleasure to know … one of the worst tempered men perhaps that ever lived.” Dickens said of his time at the school, which was the Wellington House Academy, “I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support of any kind from anyone.”

However, the inscription on his gravestone is slightly kinder, simply saying: ‘The inflexible integrity of his character and the social and domestic virtues which adorned his private life will long be cherished in the recollection of all those who knew him’. As Queen Elizabeth II was reputed to have said on one occasion, “Recollections may vary …”

Charles Dickens’s connections with St Pancras churchyard

Charles Dickens knew the area well as he spent much of his childhood living nearby whilst his parents were in the debtor’s prison. So, if you have read A Tale of Two Cities then this is the graveyard where Jerry Cruncher brought his son, Jerry Junior to undertake some ‘fishing’, The word ‘fishing’ was a euphemism for body snatching; the body snatchers would come and dig up recently buried bodies and sell them to the early medical schools for students to dissect.

This is also the area where Dickens’s school master, Mr ML Williams Jones, lived and was buried, who was his inspiration for Mr Creakle in ‘David Copperfield’. Living in a nearby street, and apparently attending his school, he said of him, “… he is by far the most ignorant man I have ever had the pleasure to know … one of the worst tempered men perhaps that ever lived.” Dickens said of his time at the school, which was the Wellington House Academy, “I had no advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no assistance, no support of any kind from anyone.”

However, the inscription on his gravestone is slightly kinder, simply saying: ‘The inflexible integrity of his character and the social and domestic virtues which adorned his private life will long be cherished in the recollection of all those who knew him’. As Queen Elizabeth II was reputed to have said on one occasion, “Recollections may vary …”

If St Pancras Old Church is open, then I recommend taking a look inside. It is like walking into an old, rustic English church. Whilst it is ‘Church of England’, it subscribes to the Anglo-Catholic tradition, which means it emphasises the ‘Catholic rather than Protestant heritage of the Anglican Communion’.

And if you’d like to make a donation towards the upkeep of this special church then because of the many burglaries, they now have credit card reading machines in the entrance porch, rather than accepting cash.

The church is considered to be one of the oldest Christian sites of worship in Britain, and is said to have been founded in AD313 or 314. It is dedicated to Pancratius, a young boy who was martyred in Rome in 304 for refusing to give up his Christian faith. I’ve written more about him in the appendix.

The first written reference to it is in the Doomsday book in 1086. It later became a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I, who allowed Latin mass to continue here throughout her reign. The church was rebuilt and renovated several times over the years, and whilst much of what we see today only dates back to the 1840s, it retains an 11th-century core.

I explain a little more of the church’s remarkable history:

Whilst this church is now known as St Pancras Old Church and still used as the parish church for this part of London, St Pancras New Church was built on the Euston Road in 1819. Its design is based on the Erechtheum, an iconic temple on the Acropolis in Athens. The octagonal tower is copied from the Tower of the Winds, also in Athens. Extensive renovations and restorations took place in the early 1950s and today it is Grade I listed as the earliest Greek Revival church in London and one of the most important 19th-century churches in England.

![]()

When you are ready to leave, the exit is just past the church. Go down the steps and turn left down Pancras Road.

Finish: St Pancras Old Church |

This is where the walk ends.

It is about a ten-minute walk back to St Pancras and King’s Cross stations and the Euston Road. If you now have weary legs, then bus numbers 46 and 214 stop a few yards along from the church garden exit. Both will take you down to the Euston Road, and around to the front of King’s Cross station.

However, if you continue to walk down the Pancras Road, you’ll pass on the right a long, low building with a faded sign saying ‘Hope’. The sign looks old, but according to the proprietor of the antiques business inside, who’d been there since the 1970s, somebody, no one knows who, painted the word ‘Hope’ some ten years ago, and they still don’t know why! He was very helpful and explained that it used to be the offices of a coal company – there was a ‘coal drops yard’ almost opposite – and when he started his business, everything was covered in black coal dust.

Opposite the entrance to St Pancras station is the Francis Crick Institute, which opened here in 2016. This is a biomedical research centre and is a partnership between Cancer Research UK, Imperial College London, King’s College London, the Medical Research Council, University College London and the Wellcome Trust. They have regular exhibitions and you can find details here.

If you still have time, there are several other places of interest nearby, the nearest being the British Library. If you continue to the bottom of the street and turn right, you’ll find the library entrance. Admission is free, and you can find out more information in the appendix and on their website.

Another interesting place to visit is the London Canal Museum – at 12 Wharf Road, N1 9RT, less than 15 minutes’ walk away.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I’m grateful to Maxine and her colleagues at the KX Visitor Centre for their assistance with information for this walk.

I must also thank my great friend Ron Drake and my wife Jane, for their invaluable help with editing and checking the accuracy of these walks and making suggestions for their improvement.

Above all, big thanks to Russ Willey for his inspiration and technical ability in being able to actually put these walks online. You can read about his web design services here.