Updated: 29 July 2022 |

|

Length: About 2½ miles |

|

Duration: Around 2½ hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

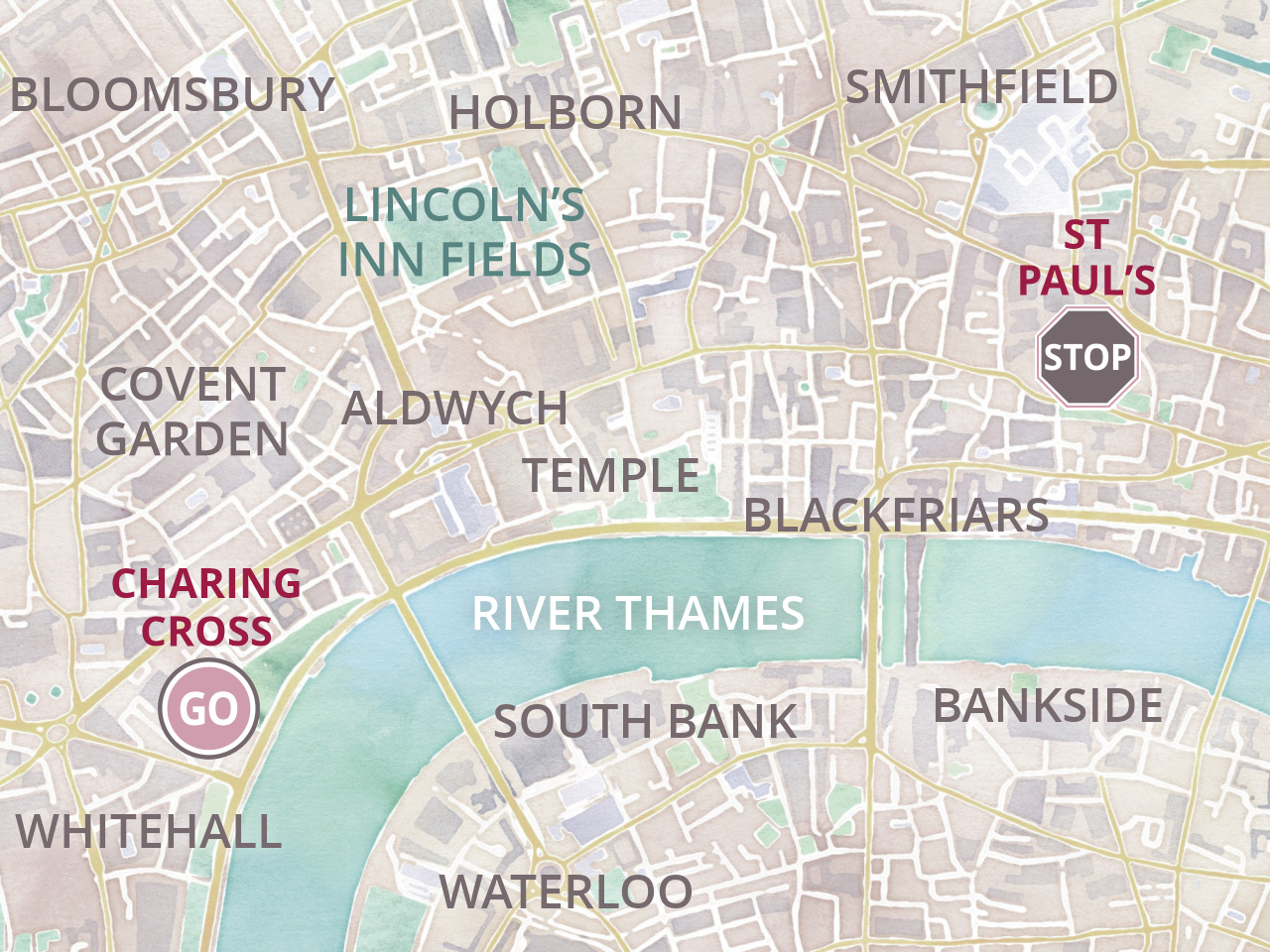

A walk from Charing Cross to St Paul’s

“In the 1660s London dominated England’s political and economic life and, with a population of 450,000, was the fourth largest city in the world. Early Stuart London was made up of two districts – the City of London, a crowded square mile within the City walls, surrounded by fields and heathland, and to the west the village of Charing Cross and then Westminster.”

“In the 1660s London dominated England’s political and economic life and, with a population of 450,000, was the fourth largest city in the world. Early Stuart London was made up of two districts – the City of London, a crowded square mile within the City walls, surrounded by fields and heathland, and to the west the village of Charing Cross and then Westminster.”

Start: Charing Cross station |

|

Finish: St Paul’s Cathedral |

GETTING HERE

The walk can start at either Charing Cross station or Embankment station.

If you are arriving by bus or on foot, then I suggest you head for Charing Cross station and turn down Villiers Street, which is on the left side of the station.

If you are arriving at Charing Cross tube station, then follow the signs to Charing Cross National Rail station and then take Exit 2, marked Villiers Street and turn to the right down Villiers Street.

Walk down Villiers Street and when you reach the end of the row of shops and restaurants on the left-hand side, turn into the narrow gateway and walk down the flight of steps and along the terraced passageway known as Watergate Walk.

If you’ve arrived at the Embankment station

From Embankment Station leave via the left-hand exit (not the riverside) and walk up Villiers Street. Pass the two sets of gates that lead into the Victoria Gardens. When you reach the little stand-alone snacks and sweets shop turn right through the narrow gate and walk down the steps into Watergate Walk, passing Gordon’s Wine Bar on the left. Continue then as from Charing Cross Station above.

INTRODUCTION TO CHARING CROSS

In case you’re wondering where the name ‘Charing’ comes from – it is an old English word meaning ‘turning’ and refers to the bend in the River Thames close by the station. The ‘Cross’ however, refers to the ‘Eleanor Cross’. Eleanor of Castile, who was the wife of Edward l, had unexpectedly died in 1290 whilst on a visit to Lincoln, and her distraught husband, asked for a ‘cross’ to be erected at each place her body rested at night on the journey from Lincoln to London. However, the ‘Cross’, situated on the left-hand side of the forecourt of the railway station, is not the original, but a replica erected in the Victorian era.

STARTING THE WALK

At the beginning of Watergate Walk you’ll see the entrance to the fascinating and historic Gordon’s Wine Bar – it’s through the unassuming doorway on your left and down several steps. It’s small and rather cramped inside, but as you’ll have already noticed, they have the use of Watergate Walk – you’ll see the line of tables and chairs, which most evenings of the week are packed with customers.

It’s the oldest wine bar in London and has been in its present form since 1890. It is a true wine bar: there really are no beers or spirits, though it has a wide selection of sherry and port. It serves simple, but wholesome food – platters of cold meats, pies or cheese, with a wide range of salad. The bar is popular with all ages, no doubt as a result of its unique atmosphere, in which time seems to have stood still. As you enter the bar you find yourself in a room with old wooden walls covered in historical newspaper cuttings and memorabilia and rickety candle lit tables, but it is fortunate in being able to use the walkway outside, which, regardless of the weather, always seems a popular place to sit. Gordon’s is open daily from 11am to 11pm.

Just a few yards along on your right is a large Italianate archway. This is the York Water Gate, built in 1626 to provide access to the river from York House, built on the Strand which runs behind here, in the 13th century as the London residence of the Bishop of York. It later became the home of George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, after whom the street you have just walked down is named. As you can see, the gate has been well-preserved.

The Strand was a popular site from the 1100s onwards for the mansions of bishops and later, wealthy aristocrats. Being so close to the River Thames (the name ‘Strand’ means land alongside a river) and well-situated between the City of London and the City of Westminster, meant they could more easily travel by boat from their own landing stage, rather than use the roads which were in such a poor condition; many were impassable in bad weather. However, when you see how far away the Thames now is from these steps, it is hard to imagine that the Duke used to be able to step directly into his boat! (I explain about the construction of the Embankment and its gardens in the 1860s in the appendix).

These grand houses and mansions were eventually demolished by developers and speculators who realised they could build many houses on the enormous plots; for example York House was demolished in 1675. All that’s now left to remind us of those once magnificent estates are their names as many of the surrounding streets were named after them – Arundel House, Essex House, Norfolk House and Savoy Palace for example.

Walk through the smaller side gate immediately before the archway and go down the steps. The plaque on the right hand wall gives further information

Turn left into Victoria Gardens. They are built on the Embankment that was created by Joseph Bazalgette as part of his amazing engineering feat in the 19th century to solve London’s appalling problem of sewage flowing into the Thames and the smell and disease that it caused.

The Victoria Gardens are known for their many memorials and statues and the first you see is of Robert (Rabbie) Burns, regarded as Scotland’s favourite son. Born in 1759 and died in 1796, he was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is also regarded as a pioneer of the Romantic Movement, and after his death he became a great source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and socialism. He is celebrated by Scots across the world on his birthday – Burns Night on 25th January.

This statue is one of three bronze casts created by sculptor Sir John Steel and was a gift to London from John Gordon Crawford and unveiled by Lord Rosebery in 1884. (The other two casts of this statue are in Dundee and in Central Park, New York.)

The wording on the front of the plinth reads –

“The Poetic Genius of my Country found me at the Plough – and threw her inspiring mantle over me. She bade me sing the loves, the joys, the rural scenes and rural pleasures of my native soil in my native tongue: I tuned my wild, artless notes as she inspired.”

On your right is a small statue to the men of the Imperial Camel Corps who fell in action or died of their wounds or disease in Egypt, Sinai and Palestine between 1916 and 1918. I think this is a lovely memorial and quite special, as I suspect few people will have heard of that corps – a camel-mounted infantry which was created in 1916 from the troops that had served in the Gallipoli campaign in the Dardanelles. The bronze statue was sculptured by Major Cecil Brown who was himself a member of the corps. The memorial was unveiled in 1921 in the presence of the prime ministers of Australia and New Zealand. The two bronze plaques on the Portland stone pedestal list the names of the 348 men who died while serving with the corps in Sinai, Egypt and Palestine. The corps was disbanded in 1919.

Next on your right is the Embankment Café, which serves a wide range of snacks and meals – (with an excellent all-day breakfast) and as well as the extensive terrace seating there are a few tables indoors for inclement weather.

On the other side of the path is a little leaning hut. For a long time I was intrigued by this and nobody could tell me anything about it. However, I eventually discovered it was built for the park keeper; it was somewhere he could sit and keep an eye on what was going on in the gardens.

On the right is a grand memorial to Lord Cheylesmore of the Grenadier Guards. He was also a well-known sportsman, chairman of both the London County Council and the National Rifle Association and during the First World War he presided over the military court martials, whose decisions now, with the benefit of hindsight, are controversial to say the least. His inscription explains he was born in 1848 and was a “soldier, administrator, philanthropist and steadfast friend”. In front of his memorial is a small pond, which according to the notice board contains koi carp, mirror carp, green tench and golden rudd, some of which you can usually see.

Through the trees, though hidden behind leaves in summer, you might be able to see the top of an obelisk known as Cleopatra’s Needle, which is flanked by two sphinxes, (If you want to take a closer look then turn right at the next set of gates.)

On the left is a statue to Sir Wilfrid Lawson (1829–1906) who was the Member of Parliament for the Lake District in Cumbria as well as being President of the Victoria Alliance (which I had not previously heard of). He was a keen supporter (and in some cases a founding member) of a number of institutions, including the Reform League, the Peace Society, the National Liberal Club, the Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade and the Temperance League. He supported the concept of Members of Parliament being paid, Irish Home Rule, the construction of a Channel Tunnel (yes, that far back!) … and he was also regarded as being a witty humourist, a great speaker … a seemingly all-round good fellow. And his motto does sound impressive – “Peace, Temperance, Fortitude and Charity”, as does his epitaph – “A true patriot, a wise and witty orator, a valiant and far seeing reformer …”

Notice the tree, now fully grown, which was planted here in 1953 to celebrate the coronation of Elizabeth II. Close by is a small plaque to commemorate the terrible terrorist London bombings on 7th July 2005.

The water fountain on the right is a monument erected to someone from whom we have all benefitted – Henry Fawcett. He set up the Post Office ‘penny stamp’ savings scheme that enabled the working class to have the facility to ‘put a little bit by’ each week, introduced postal orders, parcel deliveries and … well, it’s a long list. The inscription explains the memorial was erected by his “grateful countrywomen” … the reason being he also actively campaigned for the rights of women.

The fountain stands in front of a long brick wall, and behind it you may well be able to hear the sound of trains … this is because the Circle and District tube lines are almost directly beneath you – the wall on your right disguises the ventilation shafts that are set in the roof of the tunnels.

On the left behind the Embankment Gardens you can see two renowned classic art deco buildings, the Adelphi and the Shell Mex Building. Both were built in the 1930s on the site of the very grand Cecil Hotel, which had opened in 1896. With over 800 rooms it was the biggest hotel in Europe and one of the most luxurious. In the 1920s it was particularly popular with Americans. (And as an aside, the hotel was taken over by the government during the First World War when it became the first headquarters of the then newly formed Royal Air Force).

Both buildings are now Grade II listed. The Adelphi is currently undergoing major refurbishment and renovation which I’ve read will cost around £30 million and provide over 150,000 square feet of office space. However, being a listed building means the external art deco features, which include the art deco Portland stone façade, classic columns and sculptures that frame the building, will be retained.

Shell Mex House, recognisable by its iconic clock, was for many years the British headquarters of the Shell Mex and BP Company; they split in 1975 and Shell Mex took it over as their own head office. They in turn moved out in the 1990s and it’s now mainly occupied by Pearson PLC, one of the world’s largest publishing companies.

Next on your left is the last memorial statue in this part of the garden; it is of Robert Raikes. It was erected in conjunction with the Sunday School Union with the help of teachers and scholars of Sunday schools to commemorate his pioneering role in the Sunday school movement.

At this point there are entrances into the park on both sides and, looking through the one on your right, on the south bank of the Thames you can see the Royal Festival Hall. (And if you wanted to take a look at the obelisk, which I mentioned a moment ago, then leave via this gate and you’ll see it just along on the right.)

And now, to use Monty Python’s immortal words, ‘for something completely different’ – and also unique in London. Leave the garden through the exit on the left (behind the statue of Robert Raikes) and just 50 yards up Carting Lane, which runs up the side of the Savoy Hotel, is London’s last remaining ‘Sewer Gas Lamp Destructor’. These lamps were designed to remove excess gas from the sewers beneath the streets – if the gas built up it could cause an explosion.

The Savoy Hotel, one of the greatest hotels in the world, is another of the iconic buildings on this stretch of the river. It opened in 1869 and at the time was quite revolutionary in having electric lighting, lifts and hot running water in the bedrooms.

It closed for major refurbishment in 2007 and when it reopened three years later, it had not only been totally modernised, but despite the concerns of the many loyal and regular guests, the original grandeur and features which had made the hotel so famous were retained. I’ve put more about the Savoy in the appendix.

Diversion: Savoy Hotel |

Optional diversion into the hotel

If you’d like to take a little look inside the hotel, then I suggest you enter through the somewhat insignificant ‘River Entrance’ – it is certainly insignificant compared with the extremely grand entrance in the Strand. If there’s a doorman on duty, then just say you are looking for the reception and they’ll direct you. If there isn’t, then once you’ve passed through the outer doors take the stairs immediately on the right – pass through the door on the right and go up the next flight of stairs. Walk straight ahead and follow the corridor around, passing various small function rooms with names from some of the Gilbert & Sullivan operas – HMS Pinafore, The Mikado, Iolanthe and The Gondoliers, for example.

Almost at the end of the corridor on the left there are posh loos in case you are in need – otherwise you walk straight into the ‘middle lobby’. The hotel’s gift shop will be facing you, as will a table with an enormous display of fresh flowers. To the left is the Beaufort Bar and Kaspar’s Restaurant, whilst if you walk up the steps to the right you’ll be in the main lobby and reception area.

If you want to see Kaspar the famous black cat (I explain about him below), then walk over to left-hand wall of the lobby where you’ll see him sitting on a table against the wall – unless he happens to be dining that day.

The American Bar is on the right of the grand entrance – a small flight of stairs, lined with signed photos of some of the thousands of celebrities who’ve enjoyed a cocktail here, leads to it.

Once you’ve had a look then make your way back by the same route – there are a couple of signs to help direct you back to the River Entrance.

Walk back into the Victoria Gardens and before you turn left, you’ll see the Grade II listed memorial ‘globe’ in honour of Richard D’Oyly Carte.

Continue walking through the gardens, and next on the right is a memorial to the man who wrote the music for those Gilbert and Sullivan operas – Sir Arthur Sullivan. He was an amazing and prolific composer and considered by many to be one of Britain’s greatest. Besides the amazingly successful comic operas, he also wrote the music for many orchestral works, ballets and even hymns. (There were fourteen of the G&S operas in total, several of which are probably still as popular now as they were 150 years ago when they were first performed.). Personally I don’t think that Sullivan is recognised as much as he should be these days; so, as a great fan of his and Gilbert’s comic operas, I have put a little more information in the appendix.

Continue to the end of the garden where we cross Savoy Street – but before you do, notice on the left the small statue in the little garden at the front of the home of the Institution of Engineers and Technology. It commemorates Michael Faraday, who has been called the ‘Father of Electricity’. He had a very humble beginning – his family were too poor to send him to school, though he did go to Sunday school where he learnt to read and write. Nevertheless, he became a chemist before becoming fascinated with the idea of electricity and subsequently creating, amongst much else, the first electric generator.

Walk under Waterloo Bridge, made famous in the 1960s thanks to Ray Davies and the Kinks’ song ‘Waterloo Sunset’. This is the second bridge on the site – the first had been built in 1817, had serious structural problems and was eventually demolished in in the 1930s. The new bridge, designed by Giles Gilbert Scott, was officially opened in 1945. It consists of five 250 feet arches and was sometimes referred to as ‘the Ladies’ Bridge’ as it was built with a predominantly female workforce, because so many of London’s male workers were supporting the war effort.

(There are steps leading up to the roadway above should you wish to see more and I’ve written a few paragraphs about the bridge in the appendix).

The walk now continues into and through Somerset House – but if you’ve visited it on a previous occasion and want to give it a miss, then simply pass under the bridge and walk up the steps to the left. Turn right at the top and when you reach the Strand turn to the right. After a few hundred yards or so you’ll reach the main entrance of Somerset House where you can pick up the walk.

Once you’ve walked under Waterloo Bridge you are alongside the vast Somerset House, said to be London’s most outstanding 18th century building, which our walk takes us through.

It was built on the site of a palace built in the 1540s by Edward Seymour, the 1st Duke of Somerset, and Lord Protector of England, but before he was able to move in, he was executed at the Tower of London. The palace had a varied history over the next couple of hundred years, including being occupied by a number of different royals. It was eventually demolished and the enormous and magnificent neoclassical building that we see today was commissioned by George III and designed by the architect Sir William Chambers, opening in 1801.

Initially, it was for use by government departments, including the Stamp Office, which later became the Inland Revenue, which I explain more about elsewhere.

The riverside entrance is nearly two-thirds of the way along the building, past the vehicular access driveway, and compared with its main entrance in the Strand, it’s certainly not particularly grand.

Walk through into the lower level and continue ahead until you reach a small ‘lobby area’. Turn to the right and just a couple of yards along the corridor on your left you will see a lift that takes you up to the main ground floor. However, before you go up, walk for another ten yards along the corridor to see the elegant ‘Stamp Stair’ – note the singular – which gave access to the Stamp Office. As I’ve explained elsewhere, this was the beginnings of the Inland Revenue. If you have the energy you can climb up to the ground floor instead of using the lift – and if you do, notice how, as the staircase descends towards the basement, which is where you are now, the architectural detailing becomes less detailed and more basic, signifying the lower status of the those working on this floor. And notice also how worn the stone steps are as a result of several hundred years of use.

When you come out of the lift – or reach the top of the Stamp Stair – turn to the right and you will enter the spectacular Seamen’s Hall, now a posh lobby, with Corinthian pillars and a marble floor. Doors on the left lead directly on to the spacious River Terrace, whilst those on the right open into the vast Fountain Court. On the other side of the hall is an excellent restaurant, whilst in the adjacent corridor you’ll find the HAJ café that sells drinks, snacks and light meals. These you can either enjoy there or take out to the terrace. Further along the corridor there are toilets and if you walk to the far end, you’ll see a stone spiral staircase called the Nelson Stair (and yes, it too is singular), said to have been designed to resemble the stair on a ship. These lead up to what used to be the Naval Board Rooms, where Nelson once worked. (At one time you were able to just wander up and take a look inside the room, but visits are now only by appointment.)

From the outdoor river terrace you have excellent views over the Thames, particularly in the winter months when the trees aren’t in leaf (in summer they do unfortunately rather block the view). However, if the weather is nice it’s a pleasant place to enjoy an al fresco drink and to rest your legs.

Once you’re ready to move on then leave the Seaman’s Hall through the main doors which lead into the magnificent and enormous outdoor Fountain Court. We’re going to head to the far top of the court, where we exit into the Strand, but first a little more information about what you can see from where you are standing.

The buildings on your left and right – known respectively as the West and East Wings, were later Victorian additions to the main Somerset House. The West Wing (left side building) opened in 1856, and for many years was occupied by the Inland Revenue. Now it is primarily used as galleries and for exhibitions.

On the right is the East Wing, which was built 1831 and most of these buildings are now part of Kings College. However, there is a gift shop, another café and toilets.

Somerset House is open every day of the year except for Christmas Day and is free to enter. Tours of various parts of the building are available on selected days.

Walk to the archway at the top (north side) of Fountain Court. Under the left-hand arch you will see the entrance to the Courtauld Gallery. (It is currently closed for major refurbishment and is planned to reopen in 2021.)

The Courtauld Institute of Art – usually simply referred to as ‘the Courtauld’ – is the “world’s leading centre for the study of the history and conservation of art and architecture”. It is part of the University of London and has for many years occupied the North Block of Somerset House, previously the home of the Royal Academy of Art. It is famous for its Impressionist and Post-impressionist masterpieces, as well as important paintings and works of art from the Renaissance through to the 20th century.

From the archway turn right into the Strand. But first just a few words on what you see facing you across the road.

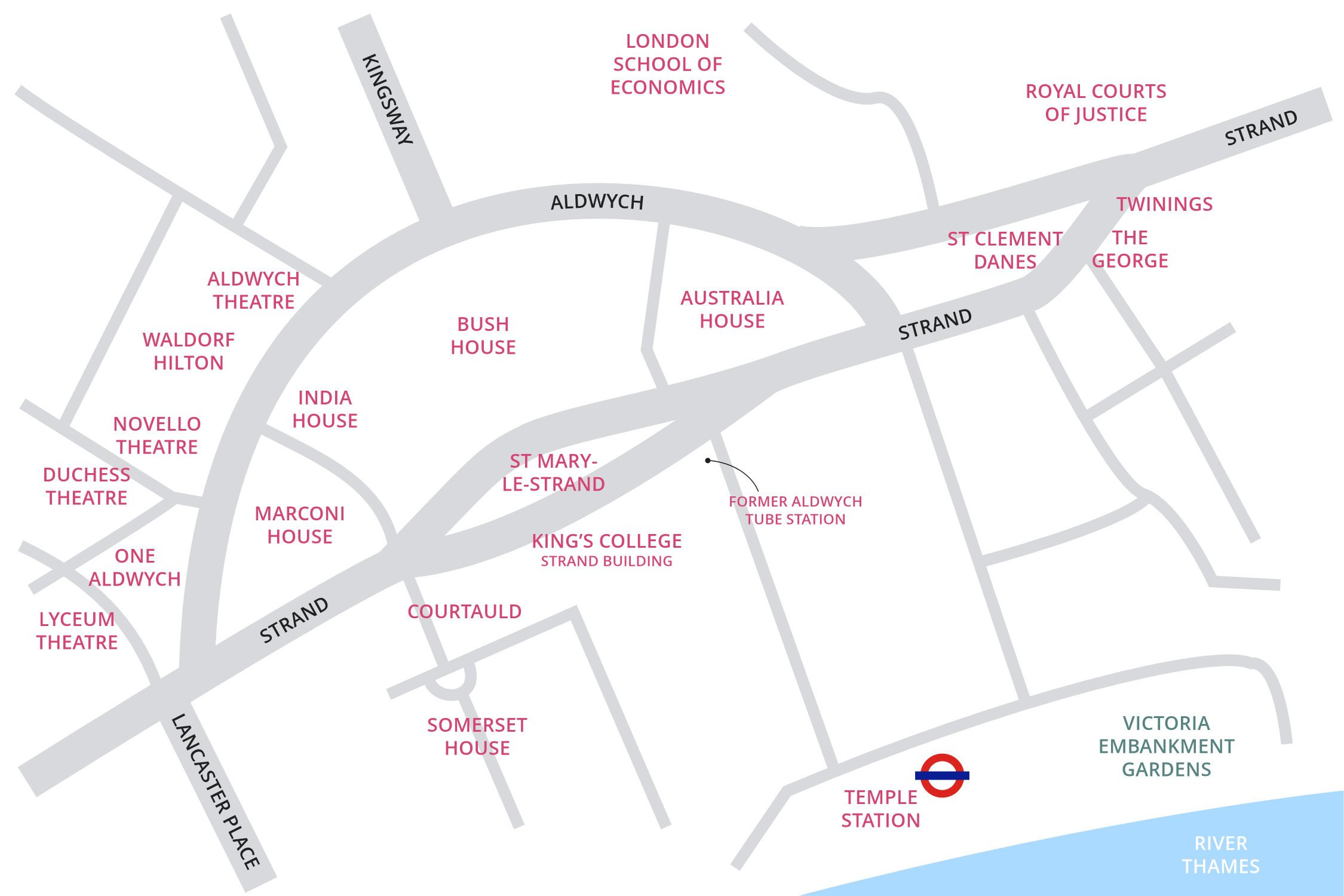

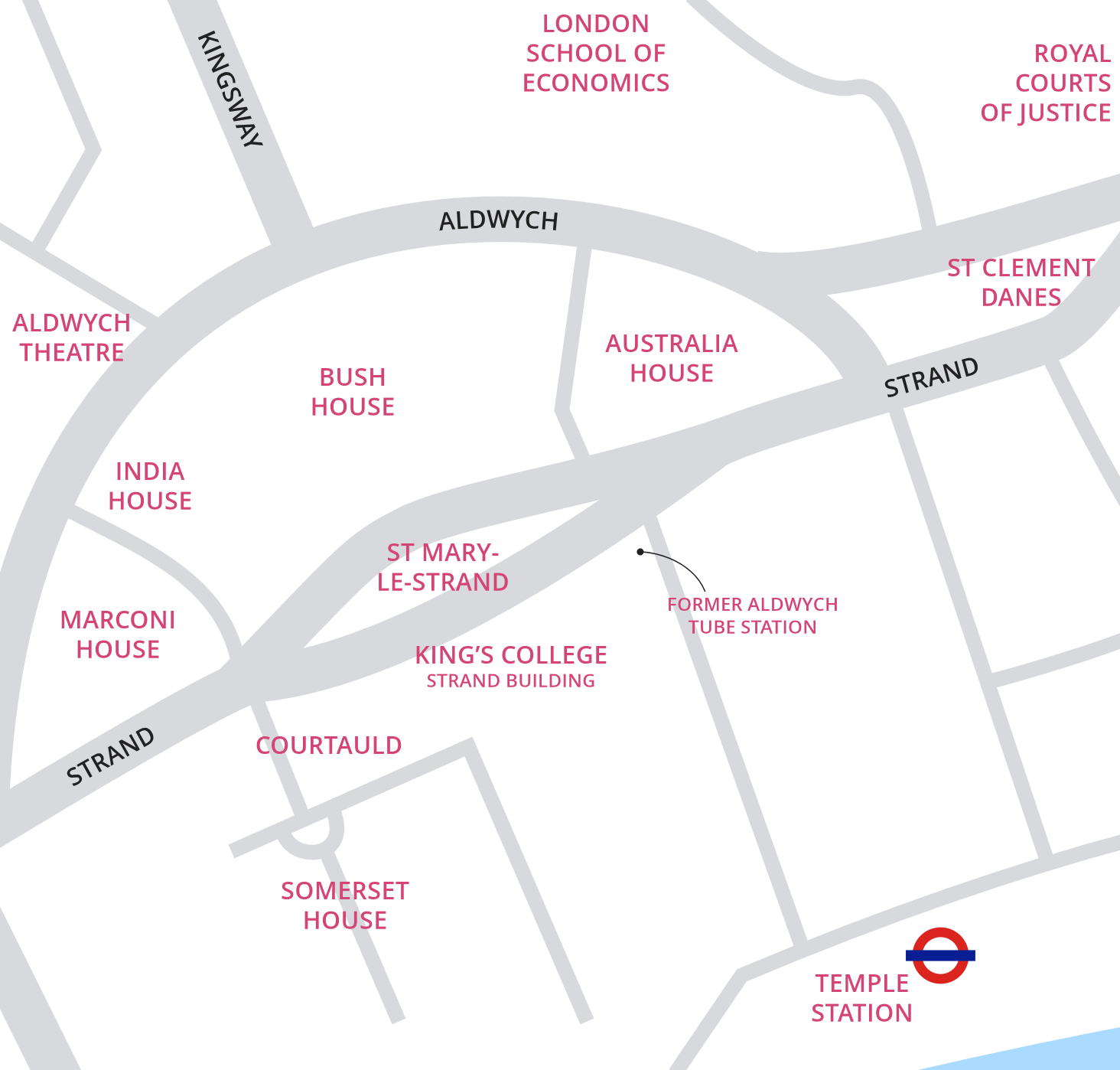

What you see is actually an ‘island’ created by the Strand dividing into two. The northern side (which you can’t see from here) splits from the Strand, curves around and becomes Aldwych, but after just a few hundred yards meets up again with the Strand.

And an aside, ‘Strand’ is an old English word meaning ‘beach or river’s edge’. Before the Embankment was built in the 19th century, the river was much wider than it is today, and the Strand really was almost at the water’s edge. And another odd little fact; it was the first street in London to have numbered addresses.

On this ‘island’ in front of you are a number of historic buildings, including two churches. The building to the left is the Marconi Building, but was originally built as the Gaiety Hotel, restaurant and ballroom. It was later occupied by the Marconi electric and broadcasting company, before being occupied by the offices of English Electric. Following a massive renovation in 2005, part of it became the ultra-modern 5-star ME Hotel, as well as home to a number of exclusive private apartments.

The large buildings in front of you are part of the Bush House complex, built by an American businessman as an international trade centre. Between 1941 and 2012 it became the home of the BBC World Service, which at one time broadcast in over 40 languages and was listened to by over 200 million listeners across the globe.

Following major renovations in 2016, much of Bush House is now occupied by Kings College London.

Across to your right you’ll see the first of the two ‘island churches’ – this is St Mary-le-Strand parish church, the official church of the WRENS (the Women’s Royal Naval Service). It was built in what is known as the English Baroque style by the same architect who later designed St Martins-in-the-Fields, close to Trafalgar Square.

Carry on walking to the right and pass on your right the rather grubby and dilapidated-looking building that is also part of King’s College. Hopefully it won’t be too long before it is renovated. However, I despair of the ‘modern’ building next to it. Whilst this style of ‘brutalist’ architecture does have its place, I don’t think it should be here, amongst so many classic and historic buildings. Next to it is the narrow frontage of the entrance to the disused Piccadilly line Aldwych (originally Strand) underground station, which closed in 1994. It is sometimes used for filming purposes.

After crossing Surrey Street, at 180 Strand you pass another ugly and enormous building described as “… an iconic Brutalist building currently undergoing a transformation into a creative hub for people and progress. It aims to foster and connect creatives, entrepreneurs, dynamic thinkers and cultural explorers by integrating the creation, display, learning and social functions of culture throughout its spaces. Having launched in spring 2016, 180 The Strand is now home to the Store X and a mix of creative companies …” (Their words – not mine.)

Cross Arundel Street and then immediately cross over to the central island in front of St Clement Danes Church. If you look across to the left from here, you get a good view of the front of Australia House with its interesting sculptures on either side of the entrance. One depicts ‘The Awakening of Australia’, whilst the other ‘The Prosperity of Australia’. The striking sculptures on the roof depict ‘Phoebus driving the Horses of the Sun’ – a bronze naked man with cloak and crown and arm raised, with four horses rearing from his chariot.

Alongside you is the memorial to former Prime Minister William Gladstone. He had begun his political career as a Conservative, but later became a member of the Liberal party and served four terms as prime minister between 1868 and 1894. Despite his great wealth, he was very highly thought of, particularly by the ‘working class’, partly as a result of the amount of time he spent undertaking ‘social work’ with those less fortunate. He was known to often walk the streets of London to talk with prostitutes and offer them financial and other practical assistance to help them change their way of life. He was also an ardent ‘abolitionist’, who campaigned long and hard to have slavery outlawed.

St Clement Danes is the official church of the Royal Air Force and there are memorials in front of it to Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding and Sir Arthur (Bomber) Harris. As the name implies, the church was built by the Danish community living in London in the 9th century. It has been rebuilt several times since.

The chimes of its magnificent bells have been known to generations of children as a result of the nursery rhyme ‘Oranges and Lemons’ – these are the “bells of St Clement’s”. The chimes are amazing, and if you happen to be there ‘on the hour’, you will be in for a treat.

Leave the church and walk around to the left. Across the street to the left you’ll see what used to be Clement’s Inn, once one of the Inns of Chancery. (These inns were places where those wishing to become lawyers would study before joining one of the Inns of Court. Over the centuries their role diminished, and they simply became clubs for the legal profession – in some cases just bawdy drinking clubs). The last incarnation of the inn was demolished in the 1960s and the present building is now part of the London School of Economics campus.

From here you can observe the magnificent buildings of the Royal Courts of Justice, which stretch down the street almost as far as you can see.

Behind the church is a small statue of Dr Samuel Johnson, who lived close by and was very well known in the area. As the plaque explains, he was a, “Critic, essayist, biographer, wit, poet, moralist, dramatist, political writer and talker”. We see his house later in the walk, when I’ll give more details.

Walk to the tip of the ‘island’, where you now get a magnificent view of the Royal Courts of Justice. (If you would like to take a closer look then I suggest you do so now, as we don’t come back this way. And, should you feel the need, there are public toilets on the ‘island’).

But first, a few words about the Royal Courts of Justice, which are the highest civil courts in the land. No criminal cases are heard here – the highest criminal courts are at the Old Bailey. It took eleven years to build and was opened by Queen Victoria in 1882. The building is said to contain eighty-eight court rooms, around one thousand other rooms and three and a half miles of corridors.

If you decide to visit (not sure you’ll have time on this occasion), you have to go through ‘airport-type’ of security, and having done so you find yourself in an enormous and cavernous hall – actually called the Great Hall – which is more reminiscent of a cathedral than a court building. It’s a maze! Long corridors, numerous flights of stairs, some of them going up four floors at least, where you find yet more courts.

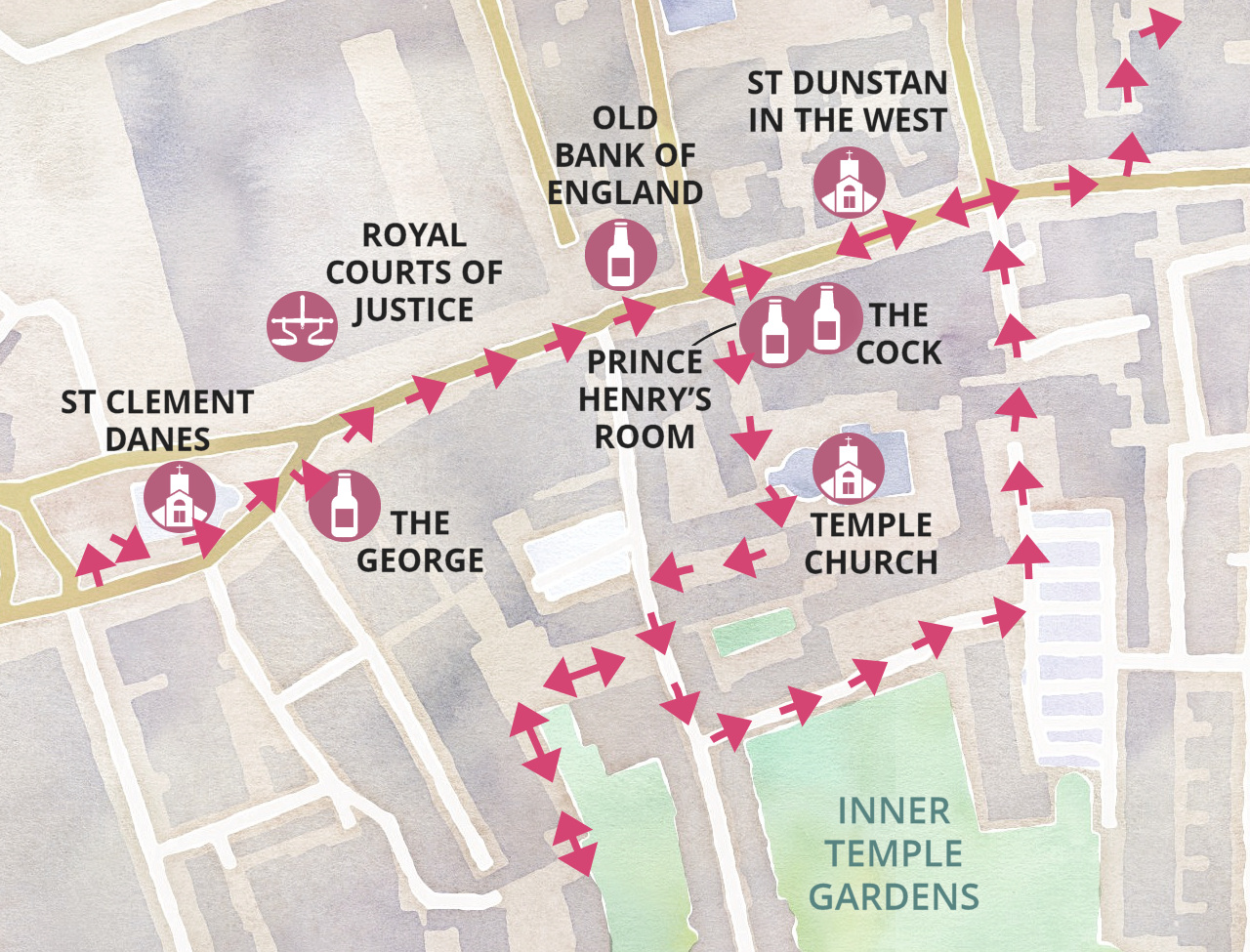

As the walk now continues on down the right-hand side of the Strand, cross over here using the pedestrian crossing – but before you do, just take a look at the lovely Tudor-frontage of the George Inn, which as the sign says now incorporates the Pig & Goose restaurant.

You may notice that many of the pubs and shops on the Strand, in Fleet Street and elsewhere in the City of London, have a narrow frontage. This was because on busy streets the wider the frontage, the higher the rent, so instead they are often ‘deep’ – going back a surprisingly long way.

Two doors down from the George Inn at 217 Strand is Twinings. Thomas Twining founded the ‘House of Twining’ in 1706 when he bought Tom’s Coffee House, which was at the rear of this building. By 1717 he had opened the shop we still see today, which he called the Golden Lyon. (Under the 19th century portico there’s a model of a lion, flanked by two Chinese men, a reminder of tea’s exotic status.) Despite being small and narrow, the shop today sells almost every flavour of tea you can imagine and, being particularly popular with tourists, is usually very busy. They offer special ‘Tea-through-Time’ sessions that you can book for £25 per person that are led by an expert in the history of tea.

Next to Twinings, at 217–220 Strand is one of the unlikeliest Pret sandwich shops you’ll see in London. It occupies part of what used to be the large Law Courts branch of Lloyds Bank. To my mind they have done an awful job of the conversion, seemingly losing most of the original features. The enormous wooden doors next to it that would have led into the rest of the bank remain shut, but when I managed to enquire about what might be happening to the rest of the building, I was delighted to be told of rumours the pub chain Wetherspoon’s had shown interest. My delight is that despite their low prices for both drinks and food, when they take over old buildings of historical architectural importance they take an enormous pride in restoring as many of the original features as they can. So, let’s hope they do go ahead – they’re bound to do a better job than Pret next door.

A few yards further on, look to the left across the Strand and through the archway you can see into the open square at the centre of the Law Courts. (I can recommend doing the annual tour here on the London ‘Open House’ weekend each September, when you are allowed to roam through virtually all of this magnificent building).

A little further along you can’t possibly miss the large stone monument that sits in the middle of the road. This is Temple Bar, where the Strand ends and Fleet Street begins and marks the boundary between the City of Westminster and the City of London. (The dragon on top marks the boundary – you’ll find them elsewhere around the City).

The tradition, started by Elizabeth I, is that when the British monarch wishes to enter the City of London, he or she stops here to be greeted by the Lord Mayor of London. The monarch then requests the mayor’s permission to enter, (which also by tradition is agreed to!). The Lord Mayor then escorts the coach through to its destination.

The original Temple Bar was made of wood and although it survived the Great Fire of London, it was by then in a dilapidated state, so a grander arched Portland stone gateway was built in its place by Sir Christopher Wren. However, over the years this increasingly caused traffic congestion and in 1874 was dismantled. In 2004 it was re-erected adjacent to St Paul’s Cathedral, which we see at the end of the walk. What you see here today is actually a memorial to Temple Bar and is decorated on each side with little statues of Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales.

I’ve put more about Temple Bar in the appendix.

Almost adjacent to Temple Bar at Number 1 Fleet Street was until recently the very long-established Child & Co. Bank. This was Britain’s oldest bank, having started in business in 1559 and existing on this site since the 1670s. Being Britain’s first bank obviously means it had a fascinating history, which I’ve found difficult to condense into just a few paragraphs so, in addition to what I’ve written here, I’ve added more information in the appendix.

Although it was an exclusive bank (not like walking into your local branch of the HSBC), until it closed you could take a look inside the front door where facing you was a large rack of musket rifles. They had been used to protect the bank during the Gordon Riots in the 1780s and had been there ever since. However, I’m not sure where they have now gone.

Over on the opposite side of the road and separated from the Law Courts by the narrow Bell Yard, is a pub called The Old Bank of England – a very grand looking Grade I listed Italianate style building with ‘flaming goblets’ on either side of its entrance. This was once the ‘Law Courts Branch of the Bank of England’ which had been built in 1880 on the site of two former pubs – the ‘Haunch of Venison’ and ‘The Cock’. The Cock was moved across to the other side of the road and renamed Ye Olde Cock Tavern, and we will see it shortly.

The bank was here for nearly ninety years, closing in 1975, when it then became a building society. When that closed in 1994 it was bought by Fuller’s, the London brewery, who have done a great job in restoring the building. The inside is quite spectacular; three magnificent chandeliers, a beautifully detailed ceiling and some interesting works of art on its walls. The clock above the bar permanently shows the time when this bank branch shut for the last time. It’s worth crossing the road for a quick look inside if you have time. And a final note – its vaults once contained gold bullion – and even for a while the Crown Jewels, though I haven’t been able to determine the reasons for this.

Continuing on down the right-hand side of the road at Number 16 is Wildy & Sons, publishers of law books, whose shop has been here since 1830, whilst next to it is Prince Henry’s Room. You need to stand at the edge of the pavement to be able to fully appreciate this fascinating building and its beautiful old Tudor-style windows.

It dates back to 1610 and is another building that somehow survived the Great Fire. Originally an inn, called Prince’s, it later became Mrs Salmon’s Waxworks, an early version of Madame Tussauds and one of Charles Dickens’ favourite places to visit in his younger days. (In his book David Copperfield, he takes Peggotty “to see some perspiring waxworks in Fleet Street,” making fun of the sweaty figures.) Until quite recently it opened to the public, but no longer appears to do so.

Notice also the very old gateway next to it – we’re shortly going to walk through it into the Inns of Court, but before we do, continue on down Fleet Street for another hundred yards or so.

At Numbers 18 and 19 is Goslings, another old bank that was established in 1650 and is now a branch of Barclays. And in 1905 it was where the Automobile Association (the AA) opened its first office.

Next to it, at Number 22, is Ye Olde Cock Tavern, which as I’ve just explained was previously on the other side of the road before being demolished to make way for the building of a branch of the Bank of England, and then rebuilt here.

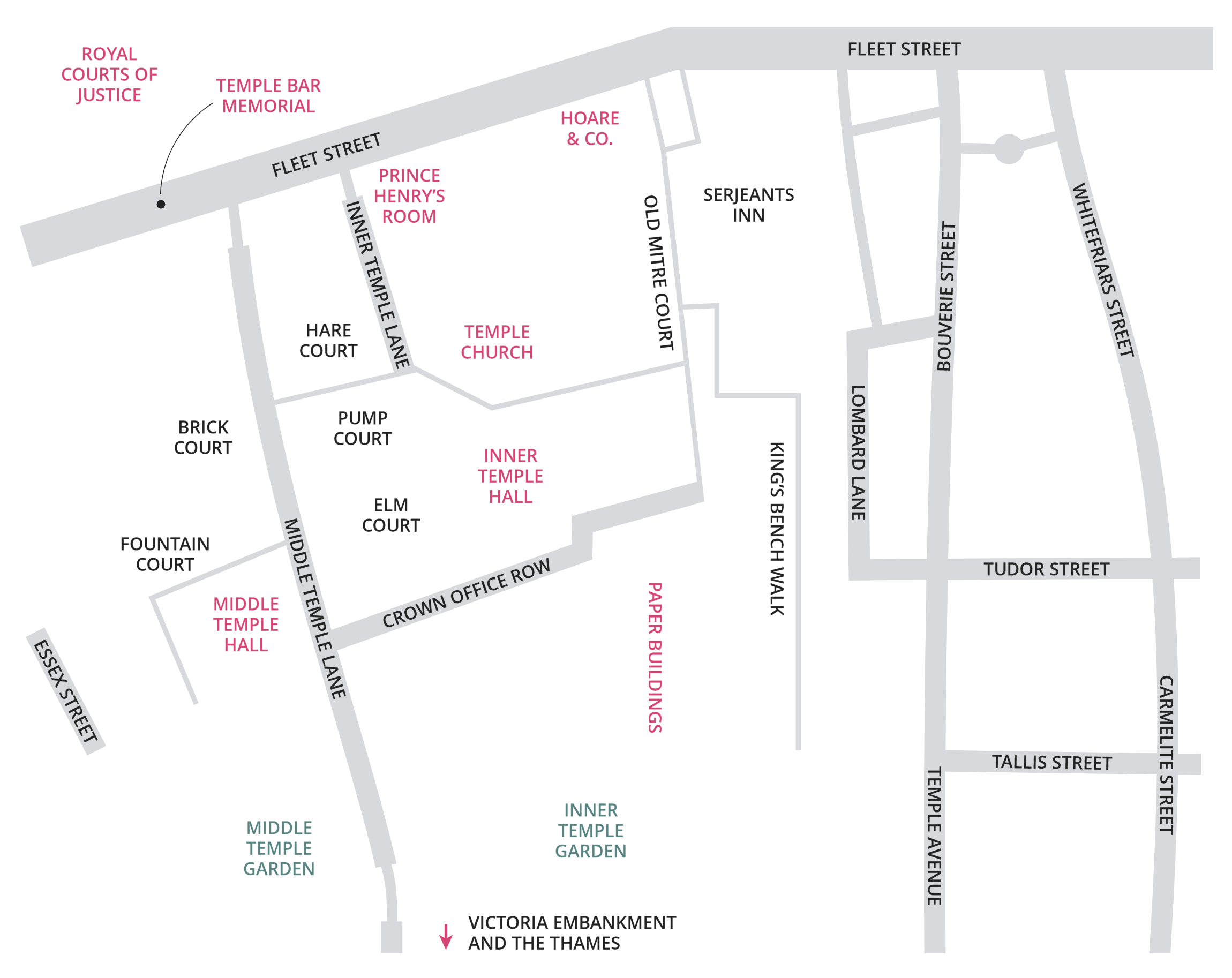

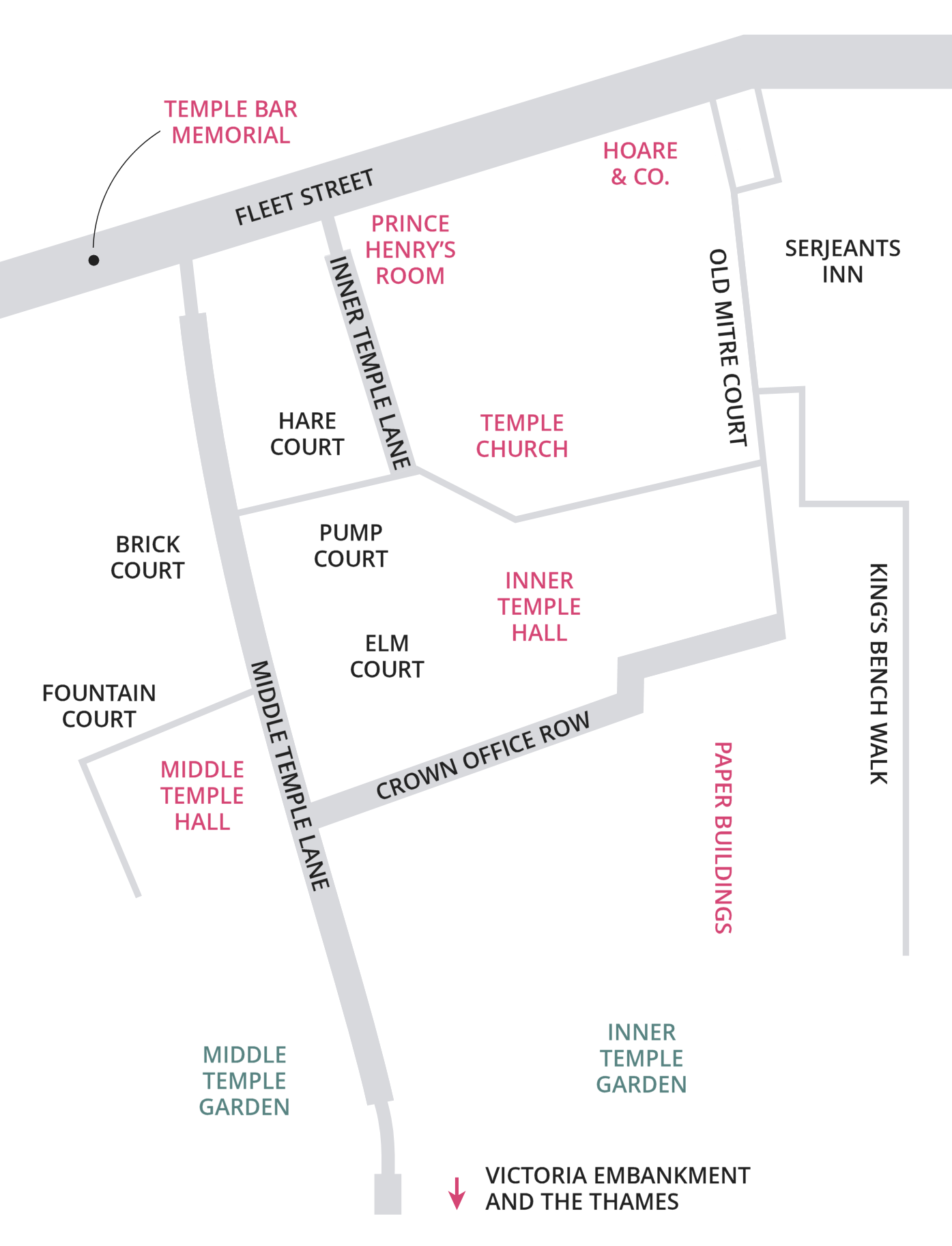

Turn around and walk back up to Prince Henry’s Room and pass through the arched gateway into Inner Temple Lane, which leads off from next to Prince Henry’s Room.

Once through the doorway you are within the grounds of the Middle and Inner Temples and you feel you could be miles away from the bustling Fleet Street. With cobbled lanes and courtyards; fascinating architecture and gardens that date back to the 13th century, this is where lawyers trained for well over seven hundred years and still work today. As you walk down the passageways you will see plaques on the doorways of long lists of lawyers who have their offices (known as chambers) inside.

The Inner Temple and Middle Temple – along with Lincoln’s Inn and Gray’s Inn – are Inns of Court that have been used by those studying the law as both lodgings and a place of learning since 1234, when Henry III banned the teaching of law within the City of London – apparently to promote and protect the colleges of Cambridge and Oxford.

(I explain more about the history of the Inns of Court in my Holborn walk which visits Lincoln’s Inn.)

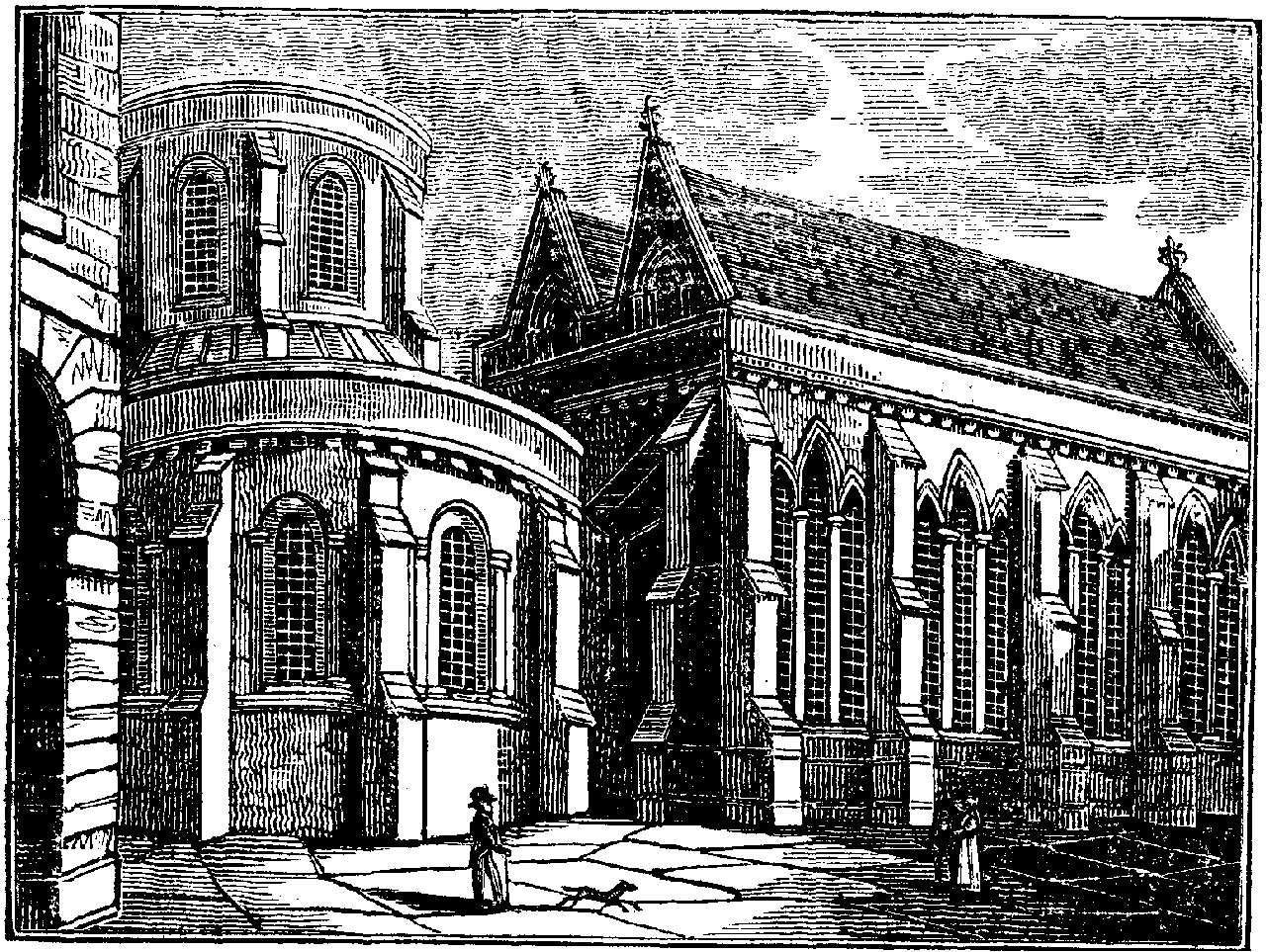

At the bottom of this passage is the Temple Church – walk around into the square to find the visitor entrance. (It’s open from 10am – 4pm weekdays and there’s an admission fee). It is considered to be one of the oldest and most beautiful churches in London and, as a result of its excellent acoustics, it regularly hosts many excellent choral and organ concerts. Indeed, one of the most popular recordings ever made by a church choir – Mendelssohn’s ‘Hear My Prayer’, which included the solo ‘O for the Wings of a Dove’ – was recorded here in 1927 and since then has achieved sales of over six million copies.

The church holds regular Sunday services, as well as being the private chapel for members of the Inns of Court, and a special privilege they enjoy is that they can be married here. The church became even more of a major tourist attraction as a result of Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code and was also featured in the film. And if you saw the film, then you might recognise the Knights Templar, mounted on horseback, on the tall column in the courtyard outside the church.

Don’t continue on past the church but turn and walk through the arches under the redbrick building on the side of the square which leads you into Pump Court (the old water pump is still there).

It leads into a larger square called Brick Court, where we turn left and then right into the Middle Temple. On your left is the Middle Temple Hall, considered to be the finest example of an Elizabethan hall in London, which was opened in 1573 by Elizabeth I. She dined here on a number of occasions, and even watched the first production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night in 1602, when some sources say he may even have been one of the actors.

The hall is around 100 feet long, 41 feet wide and spanned by a magnificent double hammer-beamed wooden roof. Its oak-panelled walls are lined with beautiful paintings and the ornate Coats of Arms of its former prestigious members. Unfortunately, Middle Temple Hall is only open to the public for special events.

Continue through the courtyard – at the far end is a pleasant area of trees, shrubs and flowers, with a large fountain in the centre. In Martin Chuzzlewit there’s a paragraph that says, “Brilliantly the Temple Fountain sparkled in the sun, and laughingly its liquid music played and merrily the idle drops of water danced and danced, and peeping out in sport among the trees, plunged lightly down to hide themselves …”

On the left, steps lead down to more gardens, (access is currently – 2020 – closed due to building works).

Head back through the square and turn right down the side of the Middle Temple Hall. After just 20 yards turn left through the archway, passing the lovely gardens on your right and more grand buildings on the left, which takes you through to the King’s Bench Walk. This enormous quadrant, surrounded by more magnificent buildings that contain yet more lawyers’ chambers, has been used for scenes in a number of historical dramas.

Turn left and walk to the top of the quadrant, passing through the archway marked Mitre Court Building, cross the small square with the terrace of the Temple Apex Hotel on the right and you’ll be back onto Fleet Street.

We will shortly be continuing to the right along Fleet Street, but first turn left and walk up for just a few yards.

On your left, at 37 Fleet Street, on the site of what was once the Mitre Tavern, is the private banking firm of Messrs Hoare. It was established here in 1672 and was one of the first banks to open in Britain. (And I’m sure some customers delight in saying – “My bankers are Hoares …”). And a brief mention of the Mitre – it was said to have been Dr Johnson’s favourite inn, and here he would regularly meet with Samuel Boswell, his great friend and later biographer. I must just mention that it was here in the Mitre when a Scottish gentleman began praising the scenery of Scotland, when Dr Johnson uttered his ‘cutting’ words of – “Sir, let me tell you that the noblest prospect which a Scotchman ever sees is the high road that leads him to England”. The inn was demolished in 1829 to enable Hoare’s to be extended.

On the other side of the road, to the left of Fetter Lane, notice the building which on each floor has large mosaic names of some of the periodicals and newspapers they’ve published, such as the Dundee Courier, Sunday Post, People’s Friend, etc. This is the London office of DC Thomson (their head office is in Scotland), who, besides being publishers of a number of newspapers and magazines, are best known to generations of children for comics such as the Beano and Dandy. The latter is no longer published, but the Beano still is, though its circulation is now around 31,000 copies a week, compared with almost 2 million a week in 1950.

To the left is the Church of St Dunstan-in-the-West. Whilst perhaps not looking particularly impressive from the outside, passers-by certainly notice its protruding chiming clock and the figures of the ‘giants’ who strike hours and quarter hours. It is thought the first church on the site was built around 990AD, however the one we see today was built in the 1830s, when it was moved back to allow Fleet Street to be widened. The two ‘portrait heads’ over the main entrance are of William Tyndale, the translator of the Bible’s New Testament, who was a lecturer here, and the poet John Donne.

There’s plenty more about St Dunstan’s in the appendix.

![]()

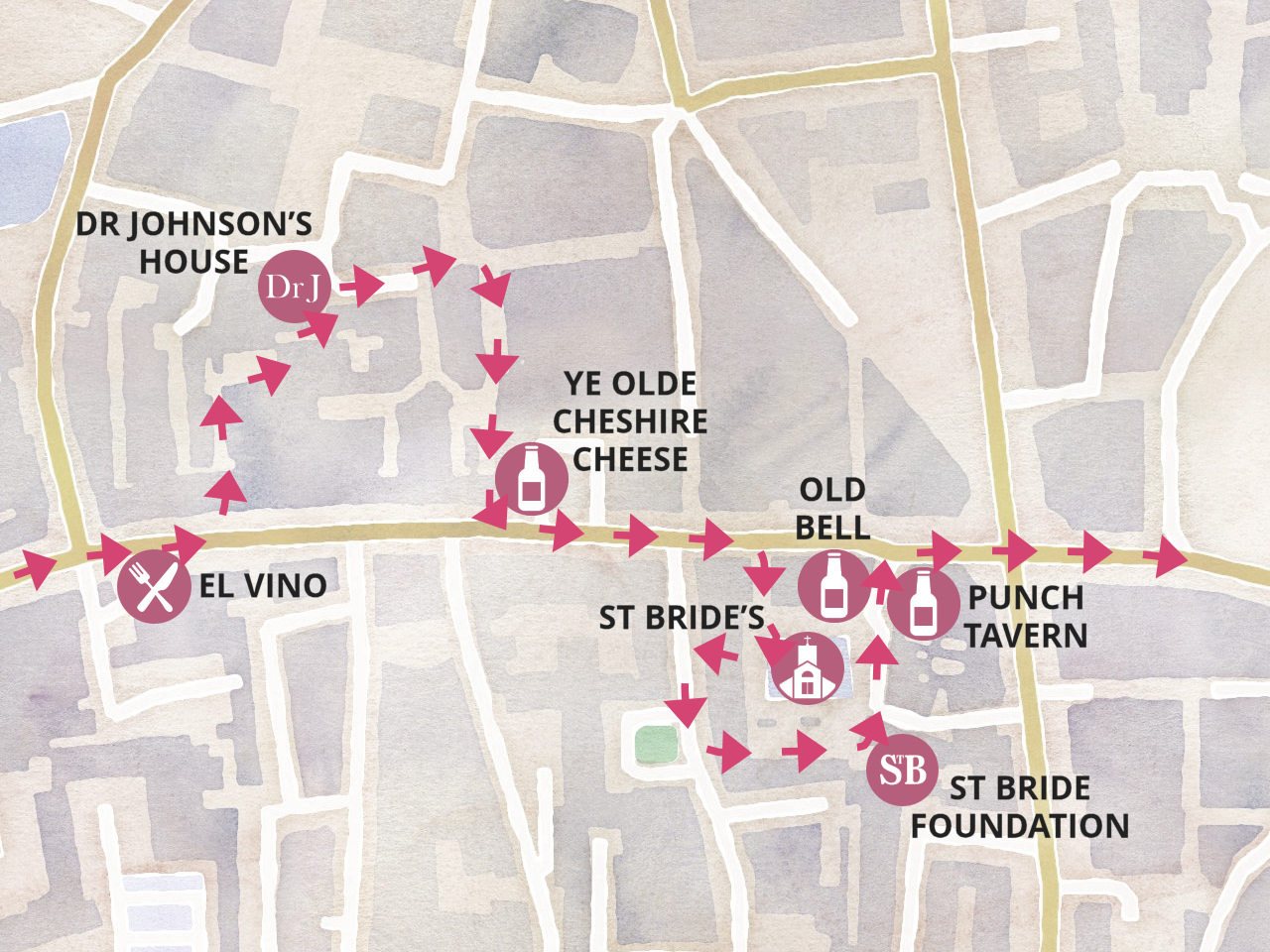

Turn around here and walk back down Fleet Street. Pass the exit from the Inner Temple we have just walked through, and next on the right you’ll see El Vino, a wine bar that opened here in 1879.

Now also a respected restaurant, it was for many years the famous, or perhaps infamous, haunt of Fleet Street journalists. Until the 1980s it had an extremely old-fashioned dress code; men were only admitted if they wore a jacket and tie and women were only allowed in if they sat in the rear room and were not allowed to approach the bar or buy drinks. This rule was challenged by a female journalist in 1982 and, hardly surprisingly, she won the case. And for viewers of the Rumpole television series, this was Pomeroy’s, his favourite ‘watering hole’.

Cross over at the pedestrian lights outside El Vino and continue walking to the right down Fleet Street.

If you look over to the right-hand side of the street, you can see what used to be the entrance to the Serjeants’ Inn – now the entrance to the five-star deluxe Apex Temple Court Hotel. This was once one of the City of London’s most important historic sites and in the 16th and 17th centuries the inn formed the legal centre of England. I’ve written a little more about Serjeants’ Inn in the appendix.

After just a few yards you’ll see the narrow entrance into Crane Court. This tiny little lane has certainly had a remarkable history, though there’s nothing much to see there now, as an ugly modern office building takes up most of the left-hand side. However, this was where a number of newspapers were printed, and it was during the time of the ‘Stamp Tax’, when each one had to have had a tax paid on it which entailed it being ‘stamped’ to prove this had indeed been paid.

There are eight of these courts (small alleyways) that lead off from the north side of Fleet Street and laid into the pavement at the entrance of each is a plaque that commemorates the street’s connection with the printing and publishing trades.

Walk past the entrance to Red Lion Court, where set in the ground you’ll see one of these engraved stones – this one says:

“In 1816, William Caslon IV produced the first sans-serif printing type, popularised by printers like R Taylor, who worked in this court.”

And in case you aren’t into typography, ‘sans’, is French for ‘without’ and serifs are the small, sometimes squiggly, additions to the top and bottom of certain characters. So, sans serif typefaces are those which do not use serifs.

After just a few yards turn left into Johnson’s Court (it’s alongside 165-167 Fleet Street) – there is a small sign, but it’s easily missed, that points to Dr Johnson’s House, which is where we are heading next.

Walk past the fountain and turn left through the arch, passing a sign that says this was also where Dickens once lived, though the house has long since disappeared. And I’ll just mention that it was in Johnson’s Court where the offices of the Monthly Magazine were situated. The magazine played an important role in Charles Dickens’ early career, as it was where his first work of fiction – A Dinner at Poplar Walk – was published in 1833.

Johnson’s house at Number 17 is immediately on your left as you enter the square. He moved here in 1748, paying a rent of £30 a year and spent much of the next nine years working on his famous dictionary, the first of the English language.

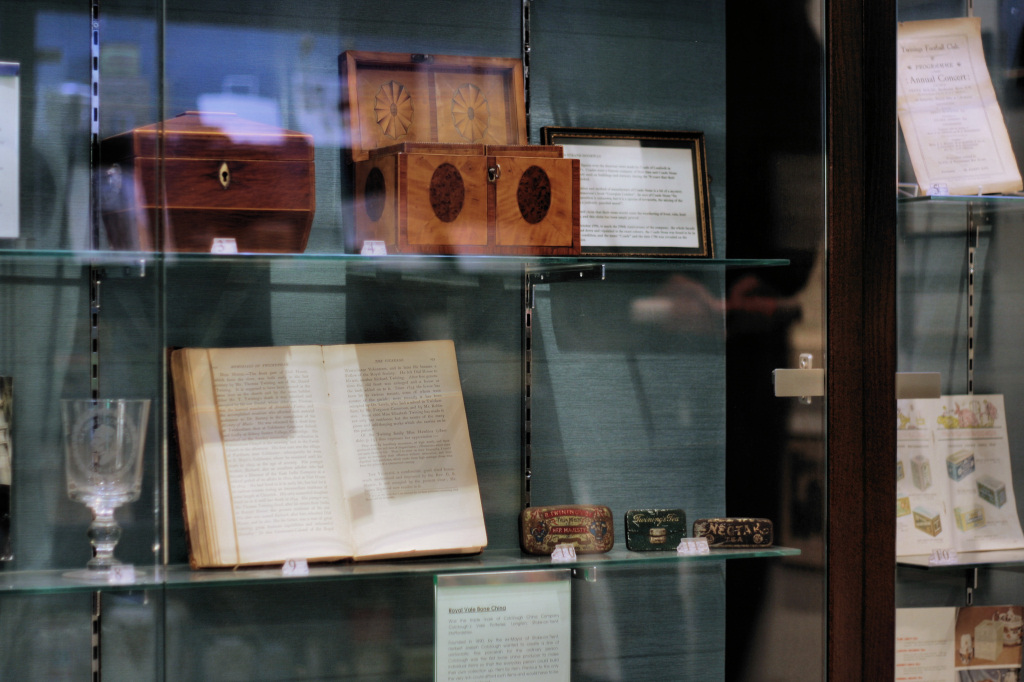

The four-storey house was purchased in 1911 by newspaper magnate Cecil Harmsworth, who later commented “At the time of my purchase … the house presented every appearance of squalor and decay … it is doubtful whether in the whole of London there existed a more forlorn or dilapidated tenement.” He paid for the house to be restored to enable it to become a museum dedicated to Dr Johnson which opened in 1914. Many of the original features have been restored, including the wooden panelling and floorboards, a fine open staircase and various pieces of period furniture. It has a number of exhibits relating to this remarkable man and retains an atmosphere that also enables you to feel as though you are drawn back to the time when he was living there. If you have time it is well worth a visit. It is open to visitors from Monday through to Saturday, 11am–5pm.

From Dr Johnson’s House, walk down to the other end of the square and at the bottom you’ll see a delightful monument to his cat ‘Hodge’. He called it a “very fine cat indeed” and as its favourite food was oysters (very cheap in those days) you can see an empty shell at his feet, though to me it looks more like a mussel shell.

From here turn to the right, pass the large protruding clock on the wall of Boswell House and at the bottom of the passage turn left and into a small courtyard with a tree.

Cross over to the far left and continue down the narrow passageway called Wine Office Court, which takes its name from the excise office once situated here, where licenses to sell wine were issued. The writer Oliver Goldsmith lived at No 6, which was where he wrote part of The Vicar of Wakefield – and it was thanks to Dr Johnson, who sold the book for him, that he was saved from eviction.

On your left is the very old ‘Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese’. There’s been an inn on the site since 1538 though the original was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and rebuilt the following year. Inside there’s a maze of small rooms on different levels – it feels as though nothing’s changed for the past two or three hundred years. And I like the board next to the side door into the pub that lists all the kings and queens from then right up to the present time.

With the inn being just around the corner from Dr Johnson’s house, it’s hardly surprising that he was a regular here, as was Charles Dickens, who also lived close by.

Turn left into Fleet Street – passing yet another court, Cheshire Court – and you can now see St Paul’s Cathedral ahead in the distance. Planning permission has been granted for the buildings on the other side of the road to be demolished and in their place will be a new set of buildings that will house a police station and eighteen new courts. These will replace various courts in the City of London, some of which are now very old and often impractical. However, the more serious criminal cases will continue to be heard in the Old Bailey.

The building you pass next was once the offices and print halls of the Daily Telegraph, which was founded in 1855. The current building was erected in 1928 and given the name of Peterborough Court, the reason being the Bishop of Peterborough once lived in a house nearby – (older readers of the Telegraph may recall that for many years it carried a daily diary column of that name).

The building is six-storeys in height with a recessed top storey, and with its grand looking Doric columns it certainly looks impressive.

Although the newspaper left the building in 1987, (if you look up above the first floor, you can still see the words ‘Daily Telegraph’ cut into the stone fascia), it was then taken over by Goldman Sachs on a lease that ends 2021 and at a rent I’ve read of £18 million a year.

Just a little further along is the striking ‘black and glass’ building that for many years was the offices and printing halls of the Daily and Sunday Express newspapers. You get a better view of the building from the other side of the road – where we go next.

Cross over Fleet Street here (at the traffic island) – once across look back to get a good view of the Daily Express offices.

Turn up into the pedestrianised St Bride’s Avenue and facing you is St Bride’s Church. It’s normally open seven days a week, so walk in to take a look at this beautiful Christopher Wren church. (When you’ve finished looking around, leave by the exit to the right of where you came in.)

St Bride’s is built on the site of one of Britain’s earliest Christian churches and dates back to the 6th century. This is the seventh church thought to have been built on the site, the fifth and sixth were both destroyed by fire – the first in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the second in 1940 during the Second World War.

A few interesting points at a glance –

- It was one of four churches within the City of London that would ring the ‘curfew bell’.

- It was the site of Wynkyn de Worde’s printing press, only the second ever in England and as such became the centre of ‘literary London’ and later, Britain’s newspaper publishing trade.

- King John was known to hold his parliament here and it was the first church in Britain to use the Book of Common Prayer, written by Thomas Crammer, the Archbishop of Canterbury in the 1550s.

- The tradition of tiered wedding cakes begun here – thanks to a baker who lived nearby and modelled his own cake on the tiered spire of St Bride’s.

- Samuel Pepys mentions in his diary having to bribe the gravedigger with six pence to ‘jostle together’ the bodies because ‘of the fullness of the middle isle’ to make way for his brother Tom, when he died in 1664.

For more information on this fascinating church, please see the appendix.

Before you leave the church, I suggest you pay a visit to the crypt – the entrance is down the stone steps just inside of the entrance. The crypt is now more of a museum – there are remnants of a Roman villa that once stood on the site, as well as remains of the foundations of the original 6th century church, which were discovered during rebuilding after the Second World War, and much more. There is even a splendid visual display of the history of the newspaper industry in Fleet Street.

Once you are ready to move on, then just a reminder to leave the church through the west door which faces the altar at the rear of the church; walk down the double height vaulted passageway called St Bride’s Avenue that runs through the centre of what used to be the Reuters building, the last commercial building in London designed by Edward Lutyens (1869–1944) known for his ability to imaginatively adapt traditional architectural styles to the requirements of the modern era.

At the end turn left into Salisbury Court. (Notice the sign on the wall of the building facing you which explains that the first ever edition of the Sunday Times was edited here by Henry White on 20th October 1822.)

Continue on for about 50 or so yards, passing a small square on your right with a monument to a past Lord Mayor of London, then look out for an archway in the in the building on your left which we walk through.

The church of St Bride’s is on your left, whilst at the far end you’ll see the St Bride Institute, a Grade II listed Victorian building.

The institute was set up in 1891 as a cultural, educational and social facility for those working in the printing industry and today has a library with two miles of shelves of books relating to the printing and related industries. The building also contains the Bridewell Theatre.

Go down the flight of steps immediately in front of the Institute’s building and take the first left up the narrow Bride Lane.

At the end you’ll find two more famous old pubs. On the left is the Old Bell, whilst on your right is … well, it’s a little confusing as the signs above windows on the side say the ‘Crown & Sugar Loaf’, whilst the signs outside the entrance of the pub in Fleet Street say, ‘The Punch Tavern’. It was originally the Crown & Sugar Loaf and when the famous weekly satirical and humorous Punch magazine was established nearby in 1840, the staff were said to have quickly adopted the pub, almost as an extension to their office, and so over time the name changed.

The Old Bell, now Grade II listed, was built by Sir Christopher Wren for the men who were rebuilding the St Bride’s Church after it had burned down in the Great Fire of London and for which he had drawn up the plans for its reconstruction. However, it wasn’t the first pub on the site, as there had been one called the Swan since around 1500. Since then a pub on the site has also been known as the Twelve Bells and the Golden Bells.

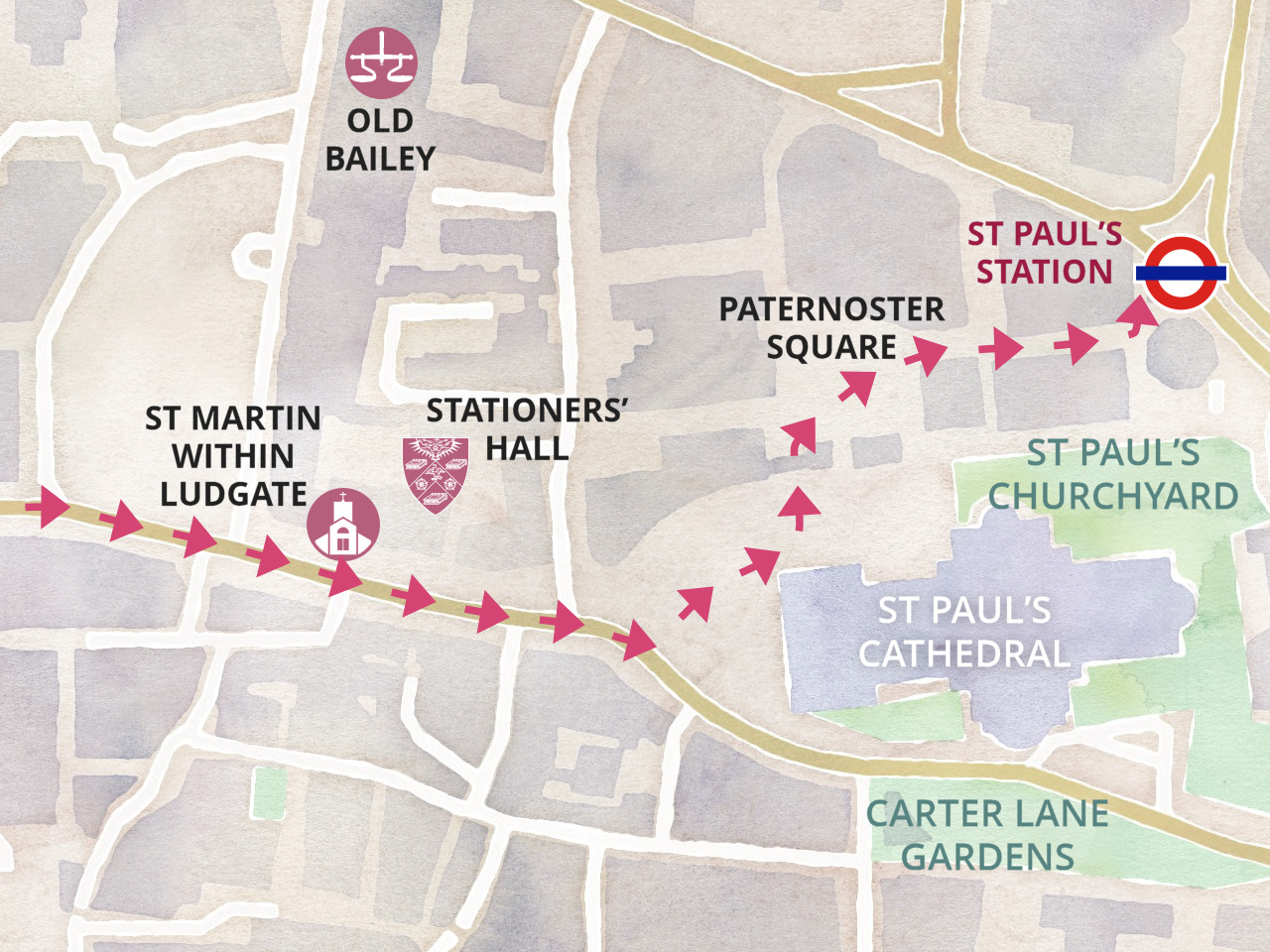

Walk the short distance down Fleet Street to Ludgate Circus. To your left at the junction is Farringdon Street, beneath which flows the River Fleet. To the right is New Bridge Street, which leads down to Blackfriars Station and bridge, whilst straight ahead is Ludgate Hill, which leads up to St Paul’s and is where we walk next.

Cross over New Bridge Street and walk up on the left-hand side of Ludgate Hill. (There are currently (2020) significant building works taking place on the right-hand side.)

Ludgate Hill was the site of the Lud Gate, one of the entrances through the original wall of the City of London, but it was demolished in 1760 as like Temple Bar, it was already by then causing an obstruction to traffic.

The hill has been the route of some of the great processions of British history – the procession to celebrate the defeat of the Spanish Armada, the celebration of the Union of England and Scotland, the military battle victories at Waterloo and Blenheim, the silver jubilee of Queen Victoria, to name just a few, all passed along here.

On your left you pass Limeburner Lane and next is the street known as ‘Old Bailey’, which leads to the world-famous criminal court (visited on my Holborn walk). Next is St Martin Ludgate, officially known as the Guild Church of St Martin within Ludgate, which was actually situated alongside the Lud Gate.

Fifty yards or so on is a narrow passage called Ave Maria Lane that leads to the Stationers’ Hall (more of that shortly, including a better way to see it). Continue on up Ludgate Hill with the magnificent aspect of St Paul’s Cathedral directly in front of you.

Keep to the left – the pavement widens out into a pedestrianised precinct, with a newly built colonnade of shops. Follow this around to the left and at the end is the magnificently restored Temple Bar gateway.

But first … as you turn left at the end of the Colonnade, look up at the wall just inside and you will see two small signs facing each other. One explains that it was here where the Grand Lodge of English Freemasons first met in 1717. The other plaque explains that it was also the site of George Williams drapery shop and home. In 1844 he and eleven others founded the YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association), now a worldwide organisation.

Walk through the archway of ‘Temple Bar’. Although I’ve already explained a little about it, I have added a few more words – and a photo – here:

Once you’ve passed through Temple Bar arch you find yourself in the spacious Paternoster Square. (However, if you need the loo at this point, there are excellent modern toilets immediately on the right after you’ve passed through the arch.)

There’s a lot to explain about Paternoster Square – so please see the appendix to read both its background as well as information about what you see today.

As you walk into the square you can’t miss the 75-foot tall Corinthian column. Built in Portland stone and with a gold leaf ‘flaming’ copper urn on top that is illuminated at night. The ‘flaming urn’ is said to commemorate the two fires that have destroyed much of this area of London in the past – the Great Fire of London and the ‘fire-bombs’ that would ignite on impact in the Second World War and which caused so much devastation in this and many other areas of the City of London. However, besides being a memorial, it also serves a practical purpose as it is a ventilation shaft for a service road beneath the square.

If you walk down Paternoster Row, you pass Thomas Heatherwick’s highly unusual 36 feet high stainless-steel sculpture, with its trickling water and illuminated panels. It’s called quite simply – and to the point – ‘Paternoster Vents’, as it is actually a very cleverly designed pair of air vents that provide the cooling of the equipment in the underground electricity sub-station below it.

If you walk down Paternoster Row, you pass Thomas Heatherwick’s highly unusual 36 feet high stainless-steel sculpture, with its trickling water and illuminated panels. It’s called quite simply – and to the point – ‘Paternoster Vents’, as it is actually a very cleverly designed pair of air vents that provide the cooling of the equipment in the underground electricity sub-station below it.

Facing you on the opposite side of the square are modern office buildings, including the new premises of the London Stock Exchange, which moved here in 2004. And if you look up at the left side of the Exchange building, you might be able to make out a giant sundial. Whilst it doesn’t show the hour of the day, rather ingeniously it does show the day and month. There’s more information on the excellent IanVisits website.

Before we move on and finish the walk, if you’d like to make a short five minutes’ diversion to see the beautiful Stationers’ Hall, then from Paternoster Square (with the Temple Bar behind you), turn left into Paternoster Row and left into Ave Maria Lane, and walk straight ahead into Stationers’ Court.

Stationers’ Hall is one of the few ancient livery halls remaining in the City of London.

In 1403 the mayor approved the formation of a stationers’ guild, whose members were text writers and illuminators of manuscript books, booksellers, bookbinders and suppliers of parchment, pens and paper. Then a stationer was one who traded from a stall at a fixed location – or ‘station’ – around St Paul’s Cathedral.

The ambition of all livery companies was to own a hall, and the stationers were no exception. In 1606 they purchased Abergavenny House, on the site of the present hall. During the early days of September 1666 the Great Fire destroyed the major part of the City of London and Abergavenny House was burned to the ground.

Work on the present Hall began in 1670 and by 1673 it was ready for use. Additions took place at the end of the 18th century, including the magnificent stained glass windows in the livery hall.

Today it is much used for corporate and private events.

Although the walk is titled ‘Charing Cross to St Paul’s’, as the walk is about to finish, if you wanted to visit the magnificent cathedral, you now have the opportunity to do so, though I’m not sure whether you’ll have the time or energy! And as there’s plenty of information available elsewhere, I’ve only included a brief mention of it in the appendix, though there’s plenty more at the cathedral’s website.

Finish: St Paul’s Cathedral |

This is where the walk ends.

To get to St Paul’s tube station then walk to the right, passing the interesting sculpture of a shepherd with his flock of five sheep. It was created by Elisabeth Frink and unveiled by Yehudi Menuhin in 1974. After the square’s rebuilding, the landlords, the Mitsubishi Estates Company, reinstated the sculpture in 2003.

Continue along the pedestrianised walk between the shops that leads into Paternoster Row (and as you do look to the right through the gap between the shops for a most unusual view of St Paul’s).

At the end turn left and you’ll see the sign for St Paul’s Underground Station, served by the Central line tube.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

During my research I discovered an amazing website put together by a lady journalist that’s packed with information on … pubs. She describes herself as a “journalist, mother-of-three and a long-time lover of pubs”. Besides the hundreds of pubs that she has visited and covered on her website, she has also written an extremely clever, concise and humorous summary of the various monarchs and their connections to London pubs. You’ll find that at King Who?

I can also recommend a recent publication called London’s Architectural Walks, written by Jim Watson and available at www.survivalbooks.net for £9.99.

Opposite the obelisk is a monument showing an angel guiding a boy and girl, a gift from Belgium to show their appreciation for us joining the First World War to help try and protect them from the invading Germans.

Opposite the obelisk is a monument showing an angel guiding a boy and girl, a gift from Belgium to show their appreciation for us joining the First World War to help try and protect them from the invading Germans.