Updated: 14 July 2024 |

|

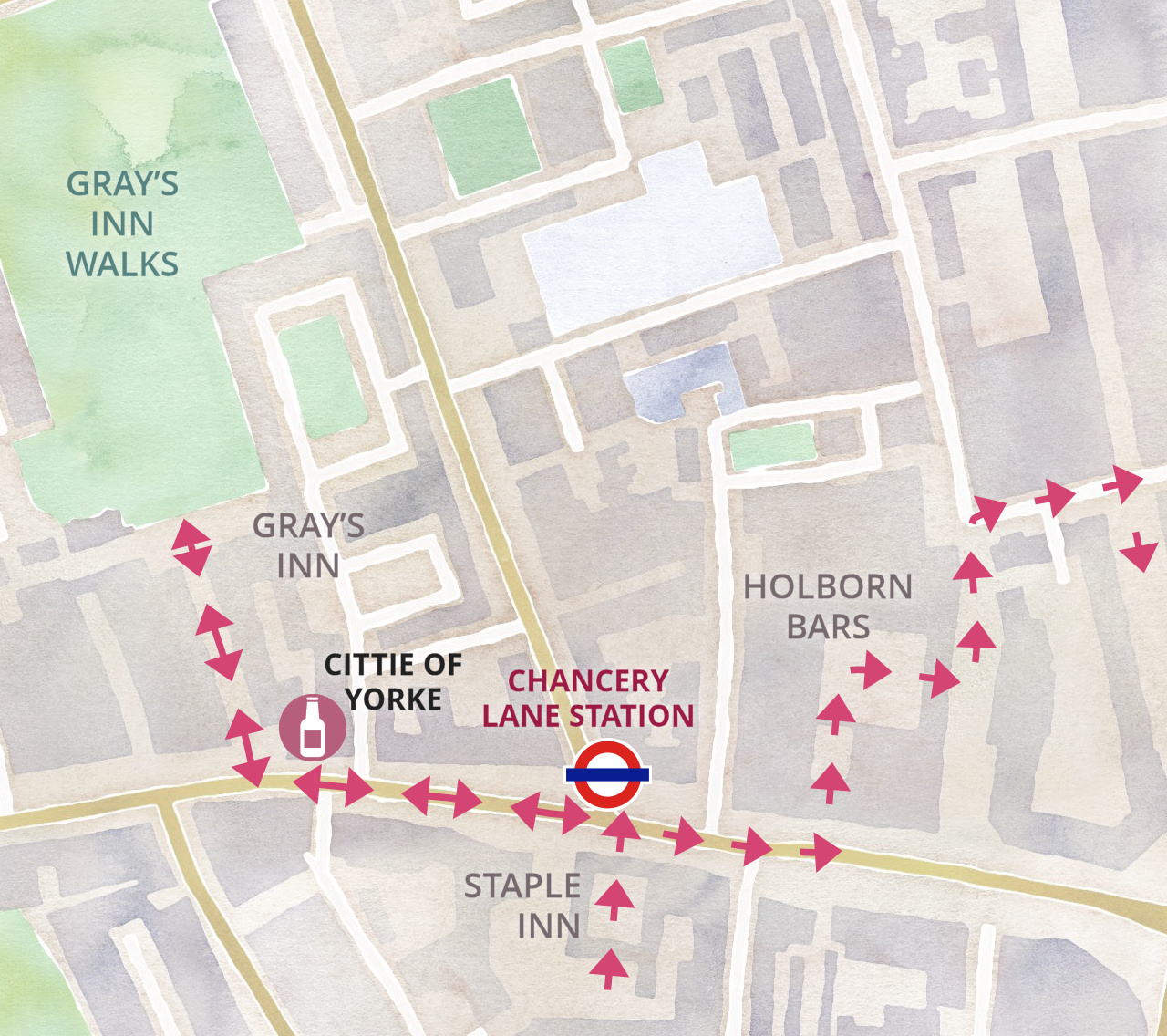

Length: About 3 miles |

|

Duration: Around 3 hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

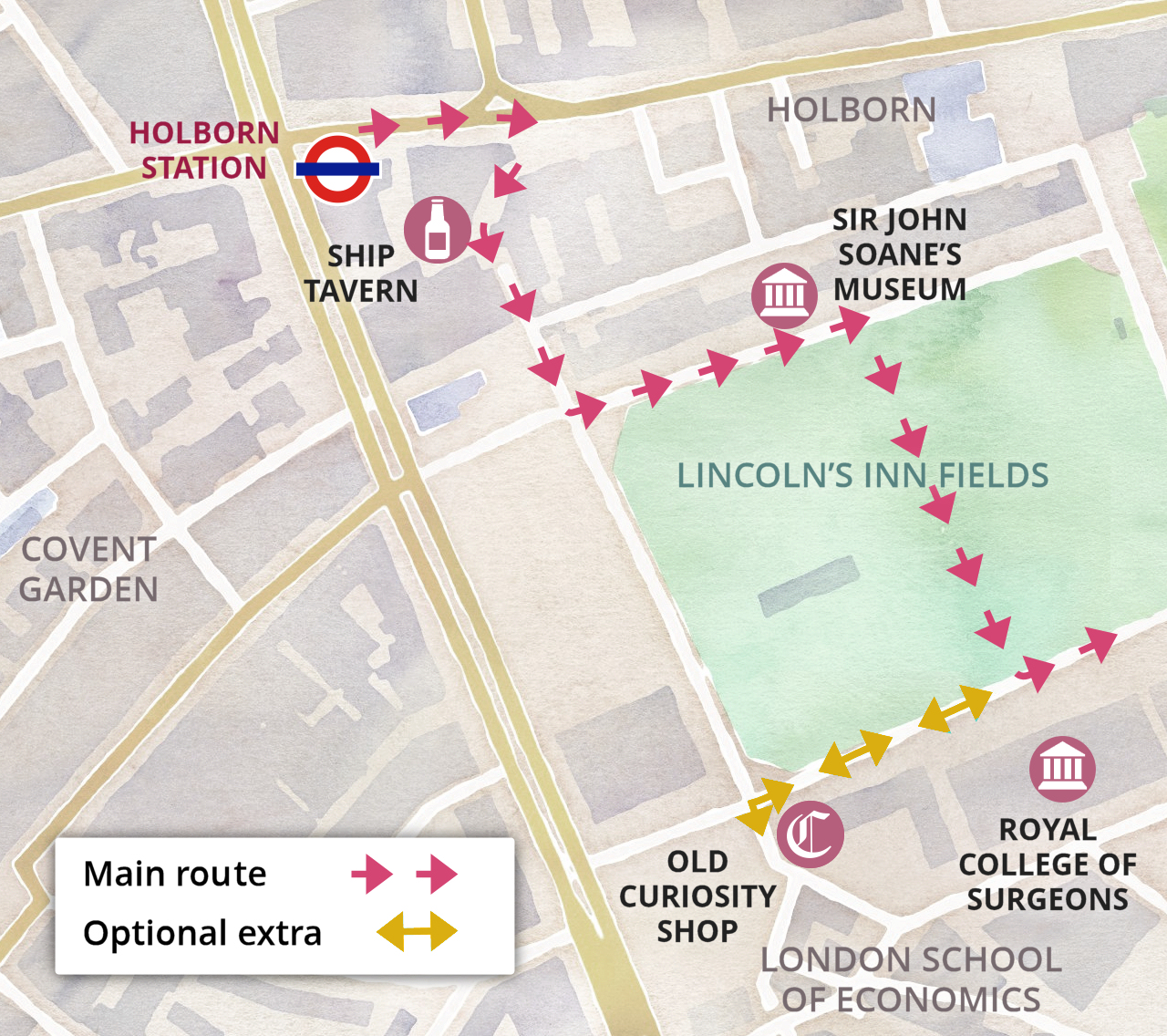

A walk from Holborn to the Old Bailey

Please note that this walk should ideally be done on a weekday as a number of places of interest aren’t open to the public at weekends.

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WALK

Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Sir John Soane’s Museum, Royal College of Surgeons, Lincoln’s Inn, the Old Curiosity Shop, London Silver Vaults, Cittie of York Inn, Gray’s Inn, the Prudential Building, Staple Inn, Hatton Garden, Ye Olde Mitre Inn, St Etheldreda’s Church, Bleeding Heart Yard, St Andrew’s Holborn Parish Church, Holborn Viaduct, Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the site of Newgate Prison, and the Old Bailey law courts.

Start: Holborn station |

|

Finish: near St Paul’s station |

WHERE TO START THE WALK

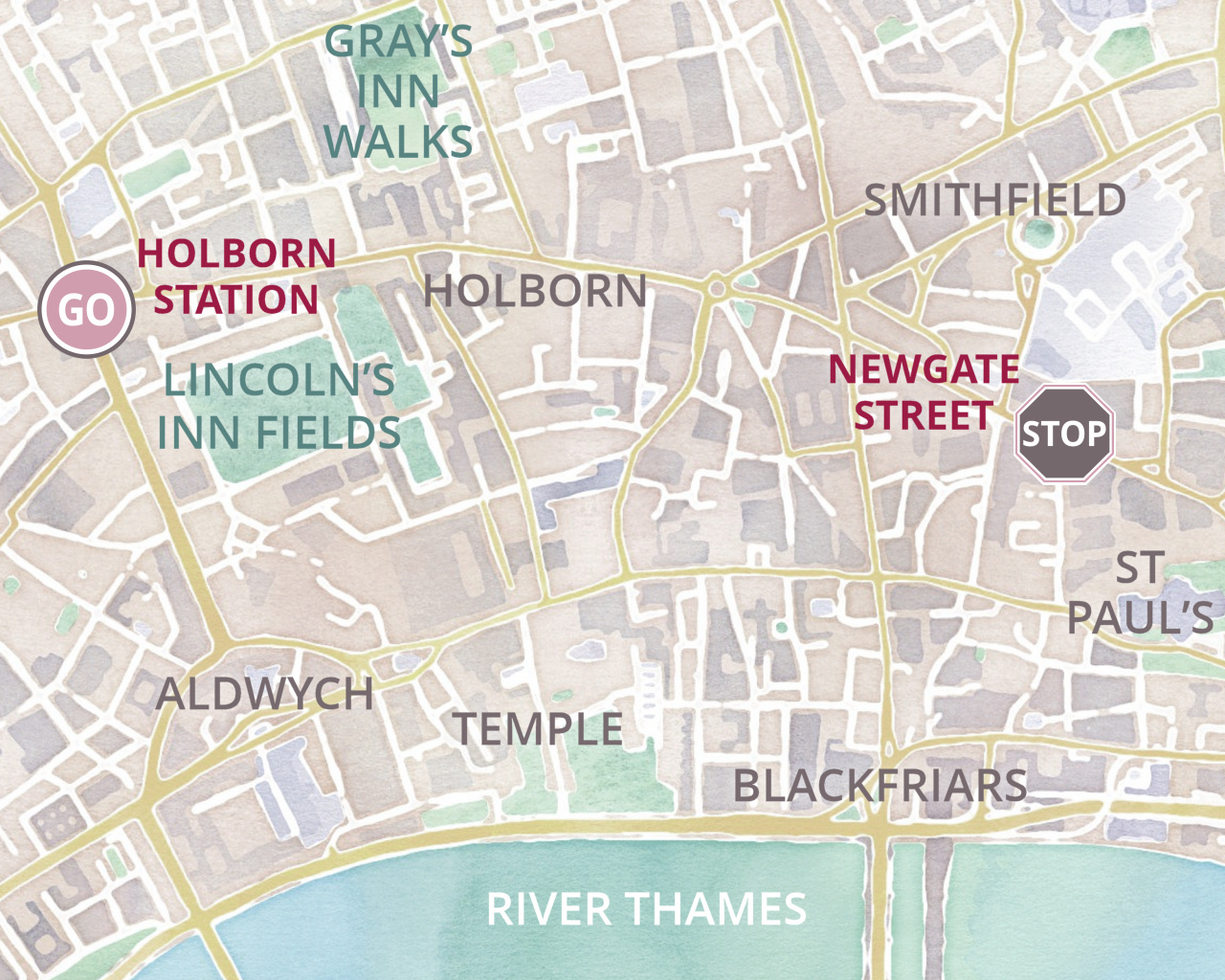

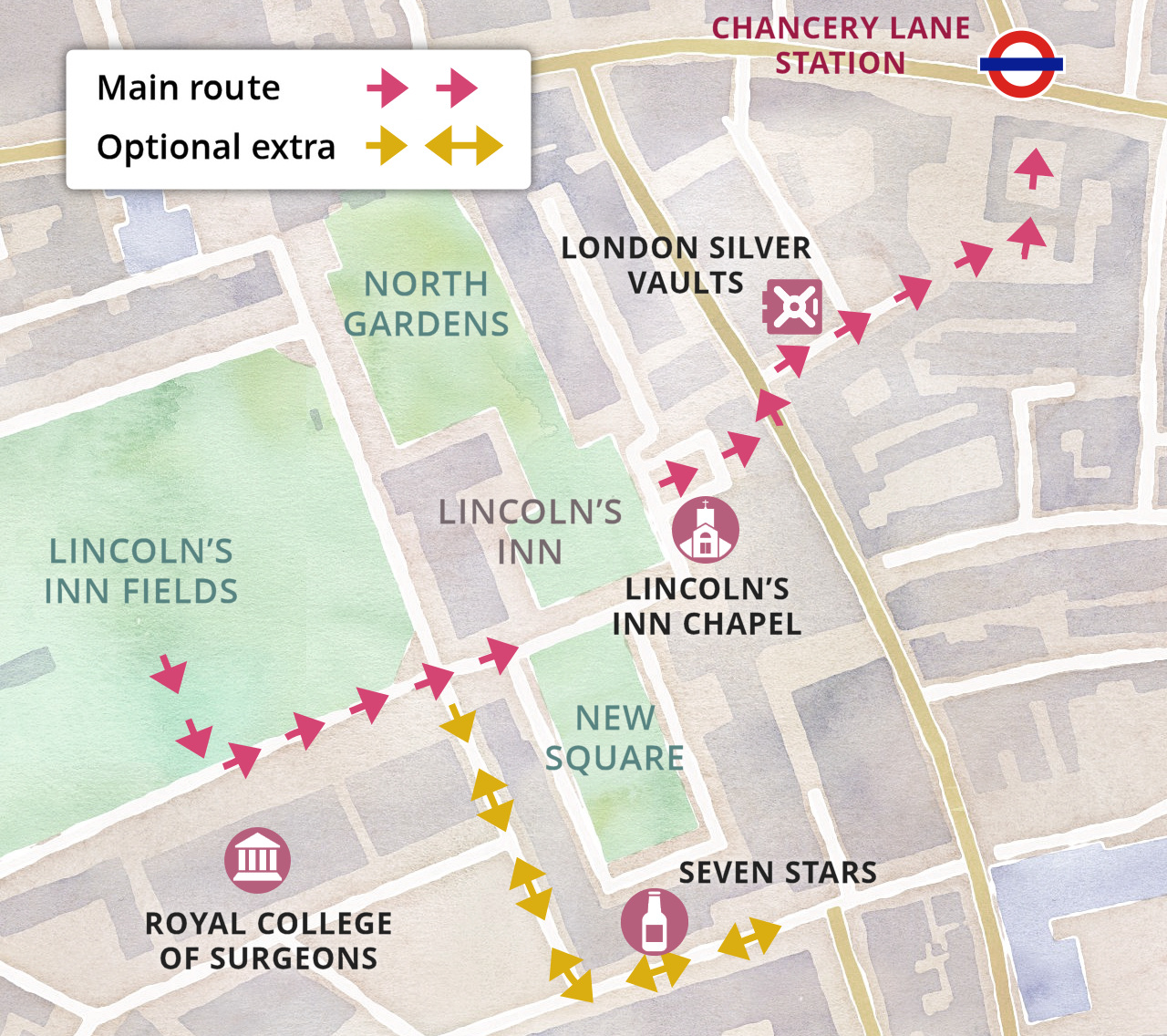

The walk starts at Holborn Station – which is on both the Central and Piccadilly lines.

If you are not arriving by underground, then head for the junction of High Holborn and Kingsway – the tube station exit is on the east side, at the start of High Holborn. Then follow the directions as below.

BACKGROUND

The name Holborn comes from the Anglo Saxon for ‘stream in a hollow’, so it was originally ‘Hol-bourne’. The ‘stream’ was actually the River Fleet, which has two tributaries – one flowing from Hampstead and the other Highgate – and they merge in the vicinity of King’s Cross and run down through Clerkenwell and Holborn and flow into the Thames under Blackfriars Bridge. However, as usual, there isn’t full agreement on this, and some historians say it might have come from the ‘old bourne’, meaning old brook, referring to a stream that at one time came from springs close to Holborn Bars and which then flowed for several hundred yards into the Fleet river itself.

STARTING THE WALK

Leave the station by the exit on the right – marked ‘High Holborn’ – turn right and walk past the row of shops – where the pavement widens there’s a Pret food outlet on the corner – turn right here and walk down on the right-hand side of Little Waitrose into Little Turnstile and then into Gate Street. You pass the Ship Tavern …

There has been a pub on this site since 1549 and it has had a fascinating history. It was used as both a place of worship and a hiding place for Catholic priests after Catholicism had been made illegal. It is worth a look inside, even if it’s too early for a drink – and the restaurant upstairs is particularly delightful with lovely old beams and about as traditionally ‘Olde English’ as you can get. I have written a little more about it in the appendix.

(The restaurant on the opposite corner was another public house; called The Sun it was also a Freemason’s Lodge.)

Walk through into the square – called Lincoln’s Inn Fields, it is the largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630’s and designed by the famous architect Inigo Jones, who also designed Covent Garden and the Banqueting House in Whitehall.

As you enter the square turn to the left and walk past a row of rather magnificent terraced houses. Many were badly damaged and some completely destroyed in the Second World War, but later rebuilt almost exactly as they were.

Number 11 is the home of Sir John Soane, the famous neo-classical architect, who amongst much else designed the Bank of England. His house has been turned into Sir John Soane’s Museum, which is open to the public from Tuesdays to Saturdays.

Soane was an avid collector – sculptures, Greek and Roman artefacts, paintings (including works by Canaletto, Turner and, most famous of all, Hogarth’s Rakes Progress). Due to it being fairly cramped inside (being quite literally stuffed full of his eclectic collections) – there is usually a queue outside, particularly in the summer. There is no admission charge, but donations are very welcome.

After leaving the house carry on for another fifty yards or so to take a look at the magnificent houses at number 17 and 18 and also 20–23; as you can see each is built in a different style. A plaque on the front of the latter explains it was used as the headquarters of the Royal Canadian Air Force Overseas Division from 1942–46.

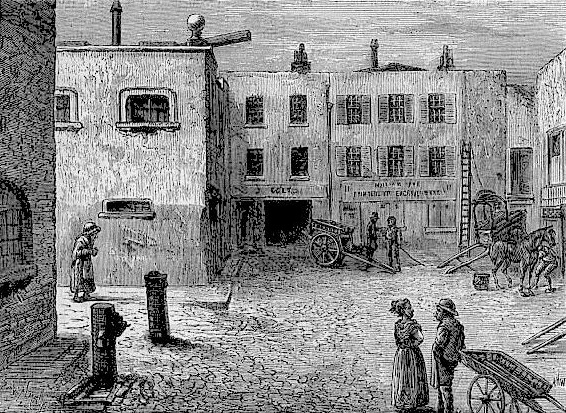

Turn back and walk for just a few yards then turn left through the gate into the park and head for the ‘pagoda’ in the centre. It is built on what was a popular site for executions – indeed set in middle of its floor is a small plaque saying, “Near this spot was beheaded William Lord Russell, a lover of constitutional liberty – 21st July 1683”.

It’s hardly surprising that the garden is said to be haunted. By day it’s rather pleasant, particularly in the summer when it’s popular with local office workers for their lunch breaks. I have been there at night and I must say that when all the lawyers and office workers have gone home it is a rather quiet, lonely and eerie place.

Apparently, it was a rather botched job, with the executioner taking four attempts to completely sever his head. After the first attempt William shouted to the executioner, “You scoundrel, I paid you six guineas to do this humanely!” (And in case you haven’t heard of Mr Russell – and I hadn’t until I came across this inscription – he was convicted of treason on account of having been involved with the plot to kill both Charles II and James, the Duke of York, in order to try and prevent a Catholic coming to the throne. A little too late, but some years later he was pardoned!

To the right of the pagoda is a café/restaurant called ‘The Fields’ that does coffees as well as a range of meals, including excellent pizzas cooked on a wood fired oven.

Leave the garden on the opposite side from where you entered and more or less in front of you is the rather magnificent Royal College of Surgeons – the building with five portico columns outside. (The sign on the slightly more modern building on its left says it’s the “Nuffield College of Surgical Science – it was, but not anymore – now it’s an extension of the Royal College of Surgeons).

Inside is The Hunterian, one of London’s most fascinating museums. It’s named after John Hunter, who in the 18th century became one of London’s most famous surgeons, renowned for both his teaching and research.

It’s open from Tuesday through to Saturday (so closed Sundays and Mondays) and whilst much of it was, and probably still is, of particular interest to student doctors it is definitely worth a visit. It’s free to go in – just pick up a visitor’s badge from the reception and take the staircase up to the first floor. The museum is on two floors and packed with thousands of specimens of every part of the anatomy of every species of life – including of course plenty of human bits! So, if you want to see thousands of jars full of livers, kidneys, brains … then this is the place for you. There’s even a little gift shop, useful if you are interested in buying a ‘skeleton t-shirt’, luminous rubber eyeballs and goodness knows what else!

I have put a little more about the Royal College of Surgeons and the museum in the appendix.

When you leave the Royal College of Surgeons you have a choice:

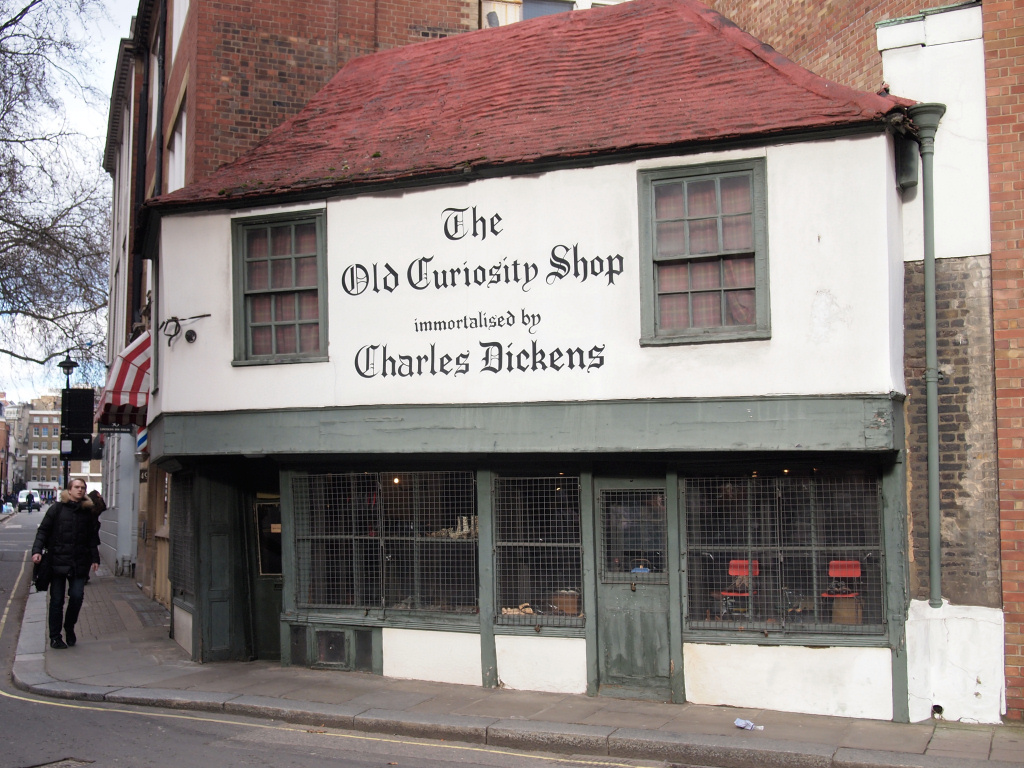

For a ten-minute detour to see ‘The Old Curiosity Shop’ – turn right (if you are facing the RCS), walk to the end of the terrace and turn left down Portsmouth Street. Just 50 yards down on the left is a tumbledown ‘house’ known as the Old Curiosity Shop.

Turn around now and walk back, past the Royal College of Surgeons – (if you didn’t detour to the Old Curiosity Shop then simply carry on as below).

On the right at the end of the street is a rather grand building and the sign over the main entrance of the at the end of the street, informs us it was once the Land Registry. It opened in 1862 as a result of a Royal Commission that proposed the setting up of a form of registration for land in Britain. However, as I’ve just said it is now one of the many annexes of the London School of Economics.

On the opposite corner there’s a well-preserved water fountain that was erected in 1880 in memory of Philip Twells, a barrister of Lincoln’s Inn and member of Parliament for the City of London. (And if you need a loo stop there’s is a public toilet 100 yards up on the left.)

You can’t fail to notice the two large ‘church like’ buildings across the road. They aren’t churches – instead they’re part of the Lincoln’s Inn complex of very historic buildings – over eleven acres in total – more of which in just a moment.

But first, another choice for you …

Our walk can continue through the gateway in front of you … but if can manage another extra ten minutes or so then I suggest you make a slight detour by turning right and walking down Serle Street.

Facing you at the bottom is the rear of the Royal Courts of Justice. Often known simply as ‘The Law Courts’, it houses both the High Court and the Appeal Courts. The main entrance and imposing frontage are in the Strand. (I won’t give any more background to the buildings as they are included in another walk.)

At the bottom of Serle Street, turn left into Carey Street and a few yards along you will see the very old Seven Stars Inn. There’s been an inn on this site since 1602 and it was originally called the Leg and Seven Stars.

In the early 17th century the inn was patronised by Dutch sailors who were said to have lived in this area. The word ‘Leg’ was said to have been an abbreviation for the word ‘League’, which was what the seven provinces of Holland were called. However, as you might guess from the displays of legal wigs in the window, it’s also been particularly popular with lawyers.

Continue for another 100 yards and you’ll see another very old establishment, a shop known as the Silver Mousetrap – which has been a jeweller’s since 1694.

And if you wonder why a jeweller’s shop has such an unusual name … in the 17th century there was a fashion for ladies to wear their hair piled as high as possible, something they achieved by winding it around wire frames that were delicately positioned on their head. Sometimes they even put a small stuffed ‘woollen pillow’ in the middle of it. These elaborate concoctions relied on a mixture of wax that was made from beef marrow and then coated with flour. When they slept (which often entailed sitting up because of the size of their hair), the various ‘products’ their hair was coated with attracted mice that would try and nest inside it! So, to try to control this rodent problem, the well- to-do ladies would have mousetraps made of silver that were then placed around their bed …. hence the name of the shop! Yuck, is all I can say!

Retrace your steps now … and if you didn’t do the detour then pick up the walk again here – pass through the entrance gateway mentioned above, which leads you into one of London’s famous Inns of Court – Lincoln’s Inn.

You are now in what is known as New Square (though it’s not that new at all!)

On your left is a flight of stone steps leading up to the magnificent, churchlike buildings we saw earlier, which unfortunately aren’t open to the public. The building on the left is the Great Hall, opened by Queen Victoria in 1845 as a replacement for the much smaller Old Hall that was built around 1490 and which we see shortly.

But first some information about Lincoln’s Inn: it is the largest of London’s four Inns of Court, which are where a qualified law student will go to continue their legal training if they decide to become a barrister as opposed to a solicitor. Their training at this point becomes quite different; for example a barrister is the person who would attend court on behalf of a solicitor.

Records show that Lincoln’s Inn was already in use by 1422 and was the first of what were at one time, nine Inns of Court in London, though as I say, there are now only four. I find the background of the Inns of Court to be quite fascinating, so I have written a little more information in the appendix.

There are many mentions in literature of the Old Hall, one being in Charles Dickens’ Bleak House …

“London. Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather … Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits* and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping, and the waterside pollutions of a great and dirty city … and hard by Temple Bar, in Lincoln’s Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery …”.

* ‘aits’ is an old English word for little islands in rivers

Leave the terrace by the wide flight of steps that lead down into a quadrant then turn right, passing the small wooden hut that must be the smallest Grade I listed structure in London. For many years a stable hand would sit in here and wait for the arrival of horse-drawn carriages and then take the horses to the stables.

Walk back towards the New Square then turn left, passing the memorial to those from Lincoln’s Inn who lost their lives in the two World Wars. The Latin inscription engraved above it reads ‘Hospitium sociis sanguinem pro patria largitic filiis parentes’, which roughly translates as ‘Offer your solidarity in honour of the allied sons who generously gave their blood for their country.’ A brass plaque adds, ‘In memory of our comrades of the Inns of Court Regiment who gave their lives in the 1939–1945 war’, and their names are listed on other plaques.

Continue past the memorial and on your right, you’ll see the Old Hall, said to be one of the finest medieval buildings in London. It was built in 1490 and I find it fascinating that the Inn’s historical records say how barristers and students were ‘eating, drinking, debating and holding their revels in the Old Hall’, over 600 years ago. Although it has had several refurbishments, what you see today is virtually how it looked when first built.

Head towards the archway that’s just slightly to your left which will take you into Lincoln’s Inn Chapel. There’s a sign on the pillar in front of it that explains the Chapel was reopened after being enlarged in 1883, the original having been built in 1428 and then rebuilt by Inigo Jones in 1620. I’ve read that in the 18th and 19th century, unmarried mothers would sometimes leave their newly born babies here, and when this happened the Inn would ‘adopt’ the baby and care for it until it grew up. The child was often being given the name Lincoln.

When you’ve finished exploring, leave the Chapel’s Crypt at the rear and walk diagonally to the right and out through the original Gate House – until 1845 this was the main entrance to the Inn. It was erected in 1521, and the young writer Ben Johnson was said to have been one of the bricklayers. Even the large oak doors that are still in place date back to 1564!

If you are interested in seeing more of Lincoln’s Inn, there are formal tours of the Chapel and other Lincoln’s Inn buildings on the 1st and 3rd Fridays of the month at 2pm (though not in August.) Meet in the Undercroft of the chapel. The charge is £5, and no pre-booking is normally needed, though you may want to check on their website first to make sure that hasn’t changed.

Having left Lincoln’s Inn, you are now in Chancery Lane.

This historic road marks the present-day boundary between the City of London and the City of Westminster. The street was created in the 12th century by the Knights Templar for access between their original Temple in Holborn to their (then) newly built Temple south of Fleet Street, which is still there today (and features in another of my walks).

Cross over Chancery Lane and turn left and shortly afterwards on the right you will see in Southampton Buildings and a sign for the London Silver Vaults that’s just a few yards along.

This is a really fascinating place that’s well worth a visit. It’s free to enter and open Monday to Friday until 5pm and Saturdays until 1pm. The ‘security guard’ at the ground floor reception desk will ask to take a look inside your bag, and then take the steps (or lift) down to the ‘basement’. As you pass through several enormous steel doors and enter the labyrinth of small vaults you will soon see how very secure it is.

Each of these little ‘vaults’ contains a shop – and notice the steel doors at the entrance to each individual shop. No wonder there’s never been a robbery!

After leaving the Silver Vaults turn left and continue along Southampton Buildings – the rather lovely building at number 25 that you pass on the right used to be the London Patent Office and it opened here in 1855. Now called Central Court, it’s used as serviced offices.

(On your left is a rather nice coffee shop with an outdoor terrace called the Taylor Street Barista.)

Walk straight ahead to the end (not round to the left), go through the gate and you find yourself in the garden of Staple Inn. Walk down the flight of steps, follow the path around the lovely garden with its roses, figs and even a locust bean tree, pass through the archway and you find yourself in a large courtyard square.

Leave the square via the archway opposite – but as you do notice the water pump on the right of it – it’s connected to a well beneath the courtyard and surprisingly the date on it is 1937, much more recent than you’d imagine. Indeed, the water that came from an underground spring, was said to have been particularly pure and have ‘medicinal qualities’.

After Staple Inn we’re going to turn left into Holborn, a street that’s also the name of the district we’re in. But pause for a moment … there’s so much here to take in, so to hopefully make it easier, I have listed several of the things to look out for:

- Barnard’s Inn

A few yards down to the right is the entrance into a small alley marked ‘Barnard’s Inn’. Barnard’s was another of the early Inns of Chancery – places of study for solicitors, similar to the Inns of Court we saw earlier for barristers. The educational role of the Inns of Chancery had ended by the 19th century and the building was taken over by the Guild of Mercers for their school. They left here at the end of the 1950s, and some forty years later, the Gresham College moved in. Gresham College is itself another fascinating institution. It was founded as long ago as 1597 by Thomas Gresham, the founder of the Royal Exchange and one-time Mayor of London. He built up a considerable fortune which he endowed for charitable works, one being the setting up of the Gresham College which for over 400 years has provided educational facilities. To this day it still offers over 100 free public lectures each year in various locations. And for those with a literary interest, this was where in ‘Great Expectations’ Charles Dickens had Pip living with Herbert Pocket. However, unless you’re particularly interested, it may not be worth going down to look, as there’s little left of the original 15th century building.

2. Prudential Building – Holborn Bars

If you look across the road and slightly to the right, you’ll see the enormous terracotta stone building that’s called ‘Holborn Bars’, which was built as the head office of the Prudential Insurance Company. We walk through it later, when I give more information about it.

3. Dragons

We turn left – and as you do notice the stone pillars – there’s one on either side of the road with cast iron dragons on top. These mark the boundary of the old City of London. Entrance gates and stone pillars were originally erected in 1130 to mark the point where tolls and dues were collected from traders entering the City of London, as well as to prevent ‘vagabonds, rogues and lepers’ from entering the City”.

The dragons themselves are more recent; the idea for them coming from two seven-foot dragons that in 1849 had been placed outside the Coal Exchange in Thames Street. When the building was demolished, the dragons were re-erected in Temple Gardens, but then somebody had the idea of using ‘dragon emblems’ on all the boundary markers around the City, rather than the previous griffins.

Back to the walk … continue to the left, and you can’t miss the famous and rather beautiful Tudor frontage of Staple Inn, whose grounds we have just walked through.

Dating from 1585, ‘half-timbered with strip windows, gables and overhangs’, it is said to be the London’s only remaining ‘sixteenth century domestic architecture’ and is certainly among the best-preserved example of such Tudor buildings in England. Look up at the right-hand corner where you see the name ‘Staple Inn Buildings’ inscribed.

And those old enough to remember tins of tobacco might recall the picture on the front of Old Holborn Tobacco – an olde worlde, half-timbered shop – and this was it. The original shop – called ‘Shervingtons, Ye Olde Tobacco Shop’ – has long gone and I’m not even sure which one of the shops it might have been. (And I do think it’s rather in keeping with the age of the building that the offices of the headquarters of the Institute of Actuaries are situated above the shops. I like to think of them sitting up there at upright wooden desks, writing with quills and ink in leather-bound ledgers!)

![]()

Cross over Holborn at this point – (you get a better view of the Staple Inn from the other side anyway) – and then carry on walking to the left for 100 yards or so until you get to the Cittie of Yorke Inn. (Actually the name of the road here is now called High Holborn – I’m not sure whether this is the reason for it being called ‘High’, but it is in fact the highest point in the City of London – all of 72 feet above sea level.)

Take a look inside the Cittie of Yorke – even if you don’t want to stop for a drink it is well worth popping in for a look. There has been a pub on this site since 1430 and although it’s been rebuilt since, many remarkable features seem to have been preserved. These include the famous ‘long bar’, known as Henekeys, (the pub was called Henekey’s Wine Bar from 1685 to 1980). Notice the enormous 1,000-gallon wine vats above the bar, and then further along in the middle of the room is a rather unique triangular fireplace with grates on three sides. (Note the absence of a chimney – the smoke is apparently carried away by a tunnel under the floor – but I wonder how effective that might have been?)

I particularly like the elaborately carved cubicles alongside the right-hand wall, designed so that lawyers could take lunch with their clients and avoid being overheard. Under the floor there are large cellars that were used to shelter Catholics during the Gordon Riots. (Those Catholics seemed to enjoy hiding in pubs!) All in all, I think it looks more like a miniature ‘baronial hall’ than a pub.

There’s such atmosphere here – even just walking in through the ‘entrance passageway’ gives you an evocative musty wine and beer smell.

![]()

After you leave the Cittie of Yorke pub, turn right and carry on for another 50 yards or so, then turn right into a lane marked ‘Fulwood Place’ and continue to the end.

It leads into Field Court, part of the Gray’s Inn complex. Ahead of you are the Gray’s Inn gardens – we turn right and walk through the archway that leads into the large Gray’s Inn Square. At the far end on the south side of the square – directly across from where you are standing – is the Chapel of Gray’s Inn. The original chapel was destroyed at the same time as the Holker Library that you see shortly and unfortunately the new chapel is to my mind not particularly interesting. However, if you wanted to look inside, then it is normally open to the public. A plaque just inside the entrance lists the vicars through the ages – the first being William Clarke in 1581 and the most recent Michael Doe in 2011; a total of 36 names during this long period.

Now turn right and walk through the arch that’s at right angles to the one you’ve just come through – this leads you into South Square. On your left is the Treasury, whilst on your far-left side is the famous ivy-covered Holker Library. There has been a library here since the 15th century and in 1929 a magnificent new building was erected with a spectacular barrel-vaulted ceiling, as well as Corinthian pillars and crystal chandeliers – all made possible by a donation from the trust fund of Master Sir John Holker, the Treasurer in 1875. Sadly, this building and many of those surrounding it were destroyed in the Second World War. Most of the library’s collection of books was lost, though a small number of exceptionally valuable editions had been previously removed. The building you see today reopened in 1958.

On my last visit I went inside and got as far as the receptionist’s desk at the top of the staircase. Unfortunately the lady on duty said she couldn’t let me into the library as it is only for Members of the Inn, but she did let me have a quick look and I have to say it looked rather ‘bland’ and not particularly interesting. And that’s not sour grapes!

In the small garden in front, is a statue of Francis Bacon, Member of Parliament for Middlesex in 1593, before becoming the country’s Solicitor General in 1607. Following that, he was appointed Attorney General, then Lord Keeper whilst finally in 1618 he was made Lord Chancellor. He died in 1626 after what was clearly a busy and successful legal life! He is particularly remembered at the Inn as in 1588, he paid for two more storeys to be built on to the library.

![]()

There has been considerable building work going on that has meant that the normal exit back into High Holborn which is in front of you at the bottom right-hand corner of South Square has been closed – if it has reopened when you visit then it’s the quickest way out – it leads you out to the immediate left of the entrance into the Cittie of Yorke pub – and to continue the walk you turn left and retrace your footsteps back down High Holborn.

However, if it is still closed then unfortunately you need to retrace your footsteps – walk back through the archway into Gray’s Inn Square, turn left through the next arch and left again into Fulwood Place, which was the way you came in. Then turn left back down High Holborn until you reach Chancery Lane, which we cross over and continue on down on Holborn.

I have written a little more about Gray’s Inn in the appendix.

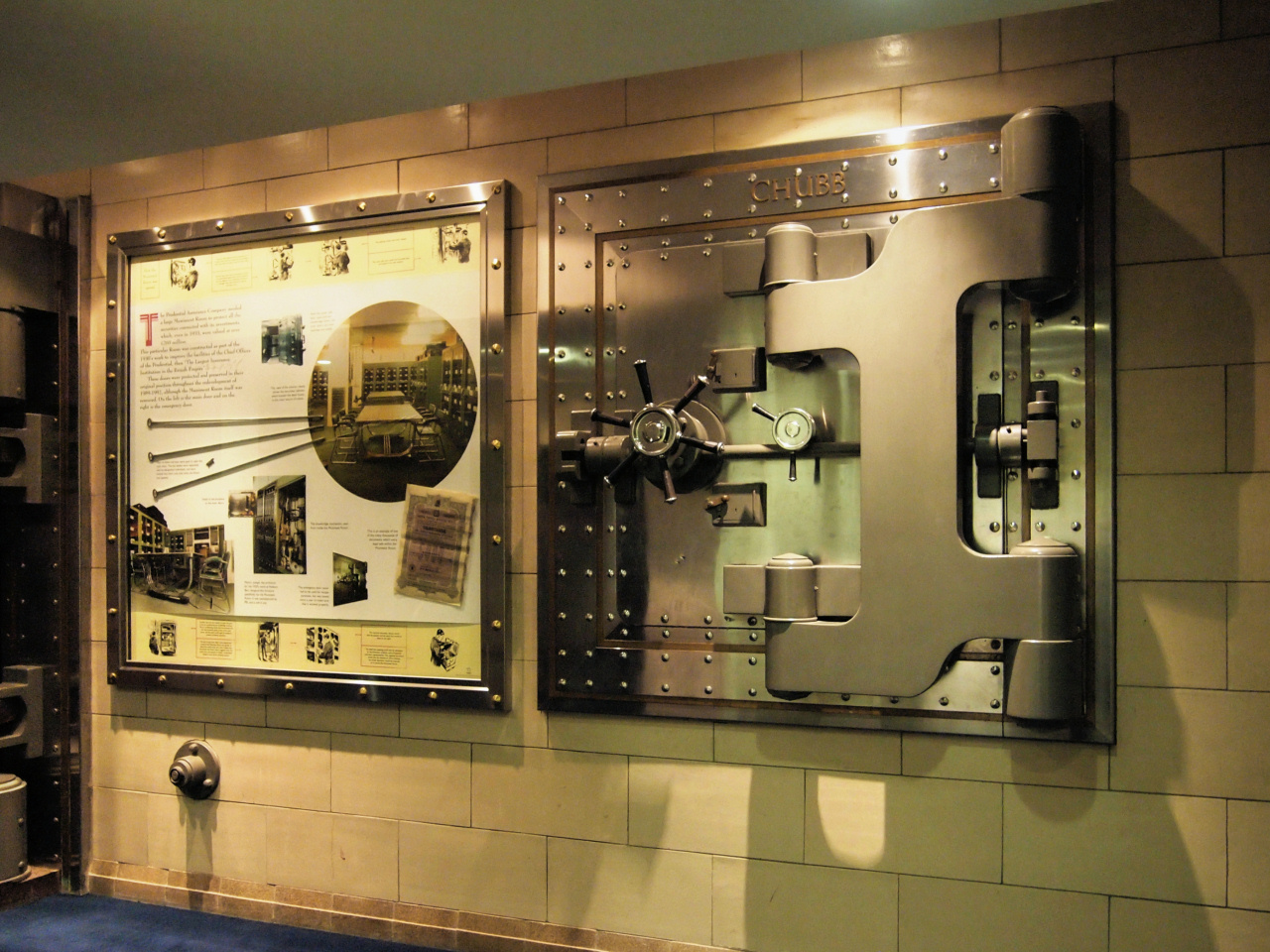

Holborn Bars

On one occasion when I was researching this walk, I chatted to the duty receptionist at Holborn Bars, saying I had read there were huge underground vaults where the Prudential once stored hundreds of thousands of their customer’s policy documents and asked if she knew whether the vaults were still there. She said they were, though now not used, and added that she would never go down to that lower level on her own as she used to get ‘cold shivers’ whenever she did and was convinced they were haunted. Not surprisingly I said I would love to see them and to my huge surprise she offered to take me down. It is a little eerie – the original massive old Chubb safe doors are still there, and it’s wonderfully preserved. But most disappointingly, I saw no ghost!

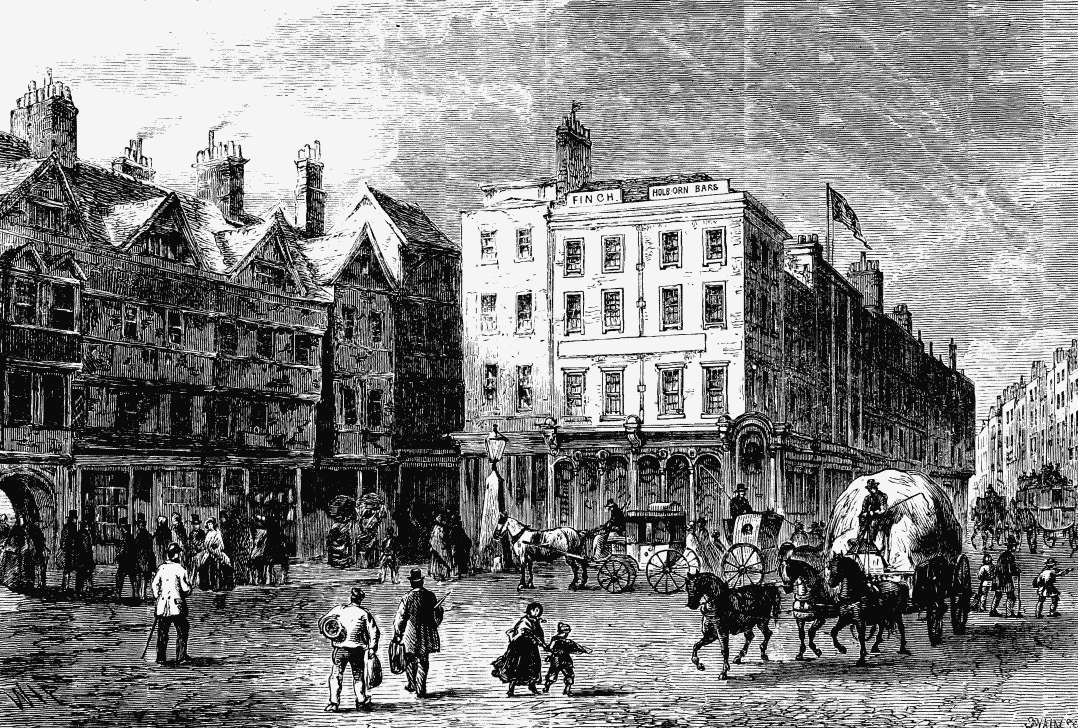

Back on High Holborn turn left – although its name changes here back to just Holborn. Originally known as Holeburnstreete, old documents dating back to 1249 record it as being ‘a main highway route for the transporting of wool, hides, corn and geese into the City’. It was also the regular route for the ‘processions’ of condemned men being taken to the gallows at either Newgate, or slightly further afield to Tyburn, close to where Marble Arch stands today. (In the appendix I’ve reprinted a poem about a man being taken to his hanging that was written in 1727 by Johnathan Swift and entitled, ‘Clever Tom Clinch going to be hanged’.)

Holborn was one of the earliest streets in London to be paved in 1417, apparently because King Henry V said it was so “miry and deep that many perils were occasioned, as well to the king’s carriages passing that way, as to those of his subjects.”

Continue back down Holborn until you reach Chancery Lane, which we cross over. Notice the impressive memorial statue of a soldier and rifle that stands in the middle of the road – it’s dedicated to the “22,000 Royal Fusiliers who fell in the Great War 1914-1918 and for those who fell in the Second World War.”

You will now be standing outside of the magnificent red-bricked Prudential Assurance building – the site is actually called Holborn Bars, due to there once being an actual barrier that marked the end of the ‘liberties’ and was where carts and carriages of ‘non-Freemen’ entering the City had to pay a penny or two-penny toll. (This was one of six such ‘bars’.)

Walk into the entrance passage at the front of the Prudential building and immediately on your left, a door leads into the part now used by De Vere for meetings and conferences. Although you can’t wander around the building itself, you can at least pop in to take a look at the wonderfully restored lobby area.

Head back out and turn left, continuing on down the access passage and into the courtyard. From here you can certainly admire the sheer size, design and impressive construction of this great building.

Across the courtyard and slightly to the left, you will see a bust of Charles Dickens, whilst to your right you can’t fail to notice the glass dome in the centre of the courtyard. This provided light into the staff restaurant below, which interestingly was only for female staff; the company believed that men should leave the building and go out for lunch, but that would have been ‘improper’ for the women employees to do! Behind the dome is a memorial to the 786 employees of the company who lost their lives in the First World War.

Leave the courtyard through a doorway on the other side of the memorial, which takes us into Leather Lane – where we turn left. (From here you can look back to again appreciate the sheer size and magnificent design of the Prudential Building.)

And I will just mention here that next to the ‘Pru Building’, between Leather Lane and Hatton Garden, was where the enormous Gamage’s department store, sometimes known as the poor man’s Harrods, once stood. I’m sure that anybody over the age of 60 or so will remember them, particularly their full-page advertisements in the national newspapers. Sadly, it was demolished in the 1970s and the current office buildings with shops on the ground floor, were erected in its place.

Leather Lane is home to one of London’s oldest markets and at one time the most disreputable, though these days it is simply known for its weekday lunchtime food stalls for office workers. Although we won’t walk that far, Number 36 was where Felton’s Coachworks used to be based, and it was here in 1802 that Richard Trevithick built Britain’s first steam coach; it travelled ten miles to Paddington and back.

Turn first right into Greville Street – and walk down to the crossroads where you enter one of the world’s most famous districts for jewellery merchants – Hatton Garden.

Hatton Garden is the name of the street that runs from left to right in front of you – we’re going to cross over then walk to the right, but before you do … on the corner at the bottom of Greville Street look left and just two doors along – at numbers 88 and 90 Hatton Garden – you will see a sign saying ‘Hatton Garden Safe Deposit Co.’ If you think that rings a bell, then you are right: it was where in April 2015, the famous ‘Pensioners’ Raid’ took place, when four elderly villains, three of them pensioners, broke in and stole £200 million worth of jewellery. The raid – I believe the biggest ever – resulted in all four being arrested, along with nine accomplices, though at the time of writing this, the ring leader has evaded capture.

Hatton Garden has been famous for its jewellery, especially diamonds, for many years but, as I explain in the appendix, it was only after 1940 when it really began to develop. This was as a result of diamond cutters and traders from the centuries old jewellery centre in Antwerp, Belgium, managing to escape the country before the Nazis invaded and they headed here. Many brought their stocks of diamonds with them, often sewing them into their clothes in case they were stopped and searched. This enabled them to quickly set up business again. Few could afford to open a shop, so they did their buying and selling whilst standing in the street, but as they became more successful, they did begin to buy their own premises, and now virtually every shop in the street – and many in the surrounding area – are jewellers. All this may soon change, for as I explain in the appendix, the rapidly rising rents are driving them out. This would be sad as it is another unique part of London’s fascinating history.

![]()

Turn right down Hatton Garden – walking past the scores of jewellers on both sides of the road. It amazes me that to my knowledge, no one has yet attempted to rob one of these shops. There are no visible signs of security other than the occasional heavily built, black suited guys with ear pieces that you might see outside a shop or walking around.

Walk almost to the very end and next to the shop at No. 10 Hatton Garden – (Smith & Green and ‘Solitaire’ Jewellers) is a small alleyway called Ely Court.

Time to stop for a snack?

Ye Olde Mitre does toasted sandwiches, steak and ale pies, lamb and mint pasties and home made sausage rolls.

Time to stop for a snack?

Ye Olde Mitre does toasted sandwiches, steak and ale pies, lamb and mint pasties and home made sausage rolls.

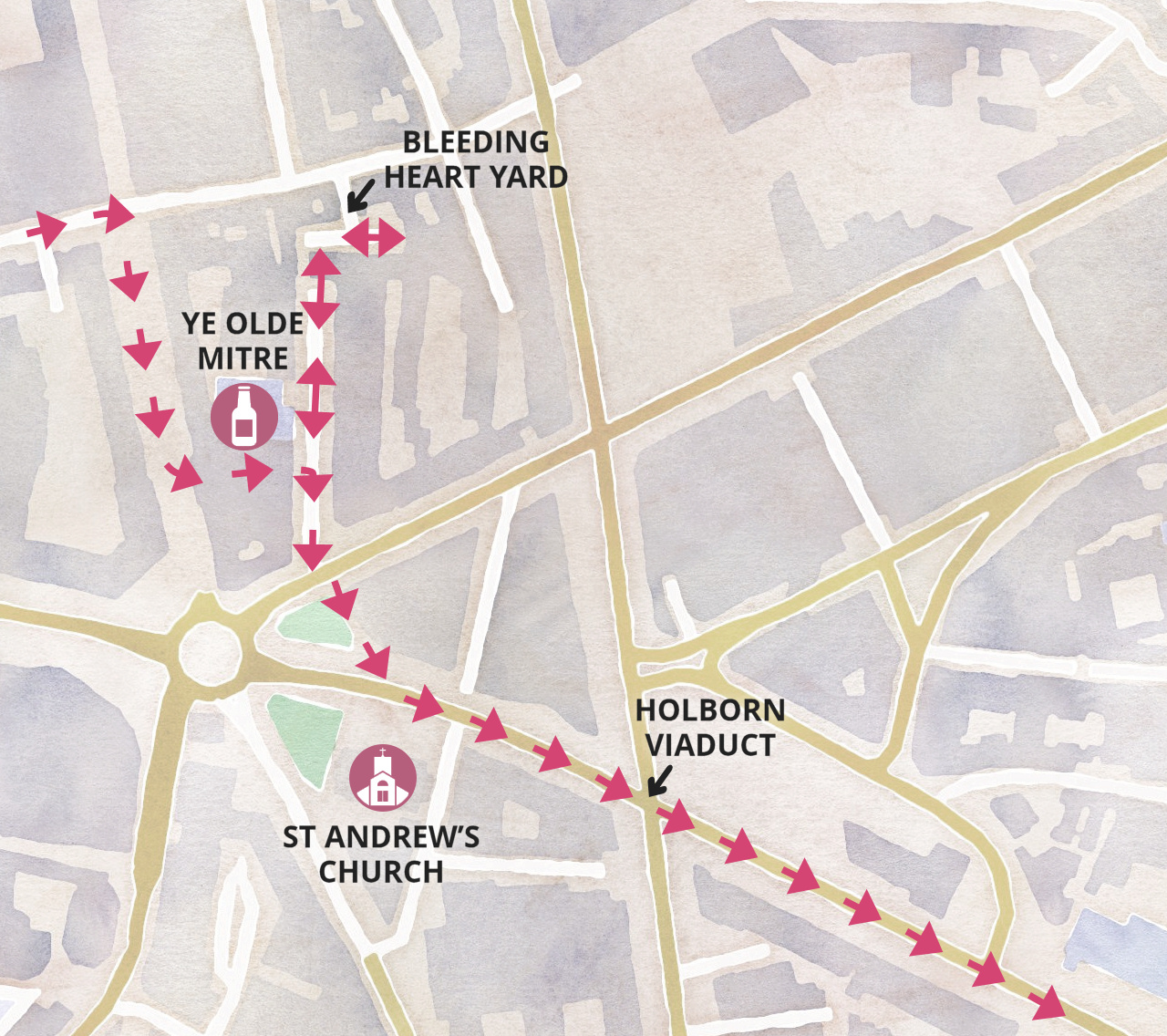

Turn to the left down it and you will come across the most wonderful old pub – Ye Olde Mitre.

Ye Olde Mitre was built in 1547 by the Bishop of Ely for his servants and acolytes, (more of him shortly). As the inn was built on the private land of the Bishop and therefore classed as being in his home county of Cambridgeshire, the Inn’s licensees had to go to Cambridge each year to get their licence renewed! Ye Old Mitre has been so well preserved – it is certainly worthwhile going in to the rear bar (reached down the side of the pub) to take a look. I love the log fire, the old chairs and the pictures on the wall. No wonder the Daily Telegraph voted it the ‘best historical pub in the UK’. Among its many claims to fame is that Elizabeth I is said to have danced around a cherry tree that was growing alongside with Sir Christopher Hatton – he was actually her ‘dancing instructor’. As we will read shortly, thanks to her help he built a palace and large gardens nearby on land he had ‘acquired’ from the Bishop. The cherry tree then marked the boundary between the him and the Bishop – and part of the tree has been preserved and is in now in the pub.

And the inn’s name? – a mitre was and still is the headgear worn by bishops. (As with much of this walk the pub is closed at weekends.)

Leave the pub and continue to the bottom of Ely Court and you are in Ely Place, another very historic and interesting part of London.

Ely Place is actually a private road that’s owned by the Crown, although technically it’s still under the jurisdiction of the County of Cambridgeshire, as it was once within the grounds of the Palace of the Bishop of Ely in Cambridgeshire – as we also shall read shortly. It has its own commissioners and beadles, (equivalent to a private constable) who have complete authority here – even the police cannot enter the street without their permission. When we leave the street, you will notice the gatehouse (today called the Porters Lodge) with the wrought iron gates. In the past the beadles would patrol the street after dark, calling out the hour and announcing the weather. Even today these gates are locked at night.

(And on a literary note … in Charles Dickens’ ‘David Copperfield’ he set Mr Waterbrook’s house in Ely Place.)

But first turn left and just 50 yards along is St Etheldreda’s Church, the oldest Catholic church in England.

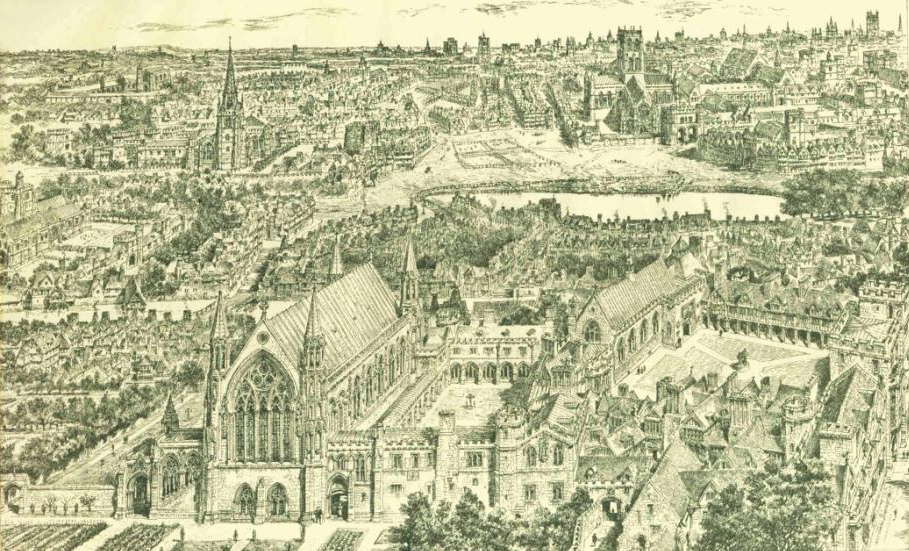

Originally the whole of this area was owned by the Bishop of Ely and from the 13th to the 16th century and where they had their London ‘palaces’, (which even today is the name given to the homes of Bishops).

The palace has long since vanished, much of it was then taken over by Sir Christopher Hatton, as I explain in the appendix – and all that remains today is what was the Bishops’ private medieval chapel – the Chapel of St Etheldreda that we see today. Whilst it survived both the Reformation and the Great Fire of London, it was badly damaged by bombing in the Second World War. (It survived the Reformation by becoming a Protestant place of worship). Over the years it has had a variety of uses; during the Civil War it was used as a prison for loyalists and later became a hospital for sailors and soldiers. It was also a school, a Welsh chapel and in 1874 it was bought by the Rosminians who turned it back into a Catholic church again. And the name Etheldreda – it was given in honour of the seventh century abbess of Ely.

From the street you can only see the eastern end of the building, particularly its magnificent stained-glass window, that commemorates the persecution and subsequent hanging of the Catholic martyrs at Tyburn in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The window is the largest in London, and you need to see it from the inside to appreciate. The church is open daily and it’s worth popping in to take a look. If you do, then walk along the corridor and take the steps down into the 12th century crypt. So much history has taken place here – it was the setting for the wedding celebrations of Henry V111 and Catherine of Aragon in 1531, which apparently lasted for five full days and nights! Quite some party! I found an account of the food that was consumed at the party, was a rather frightening amount!. However, these days everyone can ‘party like a King’, as the crypt is available to hire for private functions, ‘seating up to 150 in medieval splendour’. I find the atmosphere in the crypt rather special – sit quietly and try and imagine some of the events that have taken place here over the past 800 years. Especially as when Sir Christopher Hatton built his new mansion close by he used the crypt as a tavern and the drunken choruses and noise from the brawls would often interrupt the services in the church upstairs!

After visiting the crypt walk up the stairs to the right and, once you have struggled to open the heavy oak door, you find yourself in the actual church, where you can really appreciate the stained-glass window.

I find the history of the Palace fascinating, and I’ve written quite a lot about it in the appendix.

![]()

Continue on down Ely Place and ahead of you there’s a high brick wall. (When I first did this walk and entered the street from the far end I assumed the brick wall carried something like a railway viaduct, but it clearly didn’t!). Set into the wall is a doorway, which hopefully will be unlocked. Try turning the handle if the door is closed – if it opens you can step into the rather fascinating Bleeding Heart Yard.

If the door is locked then access can be obtained from Greville Street, but I suggest you attempt that on another occasion as it takes you too far away from this walk.

The yard’s unusual name is said to be the result of the murder of a 17th century woman who was said to be exceptionally beautiful – Lady Elizabeth Hatton, who was the widowed daughter-in-law of Sir Christopher Hatton (I write more about him in the appendix.) She was rich, young and lively and amongst her many ‘conquests’ she numbered both the Bishop of Ely as well as Senor Gondomar, the Spanish Ambassador. It was said that on the 26th of January 1626 she had invited the ‘leading lights’ of London’s society to a ball in Hatton’s house. Halfway through the evening the Ambassador saw her dancing with another man. After they had finished dancing he took Lady Hatton by the hand, danced with her once round the ballroom whereby they both disappeared into the night. The other partygoers assumed the couple had kissed and made up, but this was not the case. At daybreak her body was found in the courtyard behind the stables “torn from limb to limb” with her heart still pumping blood onto the cobblestones” … and from that day forth the yard has been known Bleeding Heart Yard.

There have been other ‘legends’ – one was that she was actually the wife of Sir Christopher Hatton and she makes a pact with the devil to secure wealth, position and a mansion in Holborn. However, on the night that she died the devil had danced with her, and then torn out her heart …

Bleeding Heart Yard also features in Charles Dickens’ novel Little Dorrit as the home of the Plornish family. He wrote …

“[It was] a place much changed in feature and in fortune, yet with some relish of ancient greatness about it. Two or three mighty stacks of chimneys, and a few large dark rooms which had escaped being walled and subdivided out of the recognition of their old proportions, gave the Yard a character. It was inhabited by poor people, who set up their rest among its faded glories, as Arabs of the desert pitch their tents among the fallen stones of the Pyramids; but there was a family sentimental feeling prevalent in the Yard, that it had a character.”

I do rather like the old poem …

Of poor Lady Hatton, it’s needless to say,

No traces have ever been found to this day,

Or of the terrible dancer who’d whisked her away;

But out in the courtyard – and just in that part

Where the pump still stands – lay bleeding a large human heart!

Today there are two restaurants within the Yard – the first, The Bleeding Heart Restaurant is a lovely, formal and quite pricey French restaurant. Then at the lower end of the Yard is the Bleeding Heart Bistro, usually with tables and chairs outside – certainly a pleasant spot to have lunch on a summers day. Finally, on the corner there is the Bleeding Heart Tavern, a pub that opened here in 1746.

We now retrace our footsteps and walk back up to the end of Ely Place, where we cross over Charterhouse Street. The building with a ‘fortress appearance’ down to the left is the head office of De Beers, the world’s largest diamond company and at one time it was the centre of the diamond trade. Founded by Cecil Rhodes in 1888, it later amalgamated with Anglo American and then had a 90% share of the world’s diamond market. Interestingly, because of the high value of the diamonds, they used to be flown in by helicopter, which would land on the roof of the building. When I first saw one land there, I hadn’t appreciated what it was doing, thinking it was strange for it to be landing on the roof of an office building in the centre of London!

Cross over Charterhouse Street and walk up the three or four steps in front of you into a miniscule ‘green space’. Almost directly across is the 15th century St Andrew’s Holborn Parish Church, whilst to the right of it, the enormous glass building is the head office of Sainsbury’s. Walk across to the church. Miraculously, it just managed to avoid being burnt down in the Great Fire of London that destroyed nearly ninety other churches in the area.

Continue walking to the left (eastwards towards the City) and the next building you come to is the grubby looking Nonconformist City Temple. Puritans are said to have worshipped here since the late 1500s, although the first records of the church weren’t until 1874. This was yet another church badly damaged by bombing and it was rebuilt in 1958, with most of the cost being paid for by John D Rockefeller Junior, the American billionaire and philanthropist.

The church is rather ‘evangelical’ in its preaching and caters for a very varied international congregation, also undertaking considerable outreach work. It is normally open during the day so take a look – its interior is modern and bland, but it certainly attracts a large congregation on Sundays.

Continue walking ahead – the road is called ‘Holborn Viaduct’ as opposed to just ‘Holborn’ where you were before – and in just 100 yards or so you come to the actual Holborn Viaduct.

Continue walking ahead, remaining on the right-hand side of the road, passing a very large modern building on the left and then after a few hundred yards on the right is another modern office development; this one is built on top of the new (in 1990 anyway) Thameslink Station that links Luton and its airport with Gatwick and other southern counties destinations.

We cross over now to the other side of the road where you will see the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. This has a fascinating history and interesting connections with the Old Bailey. It is also known as the ‘Musicians’ Church’.

Leave the church and continue on down to the junction with Giltspur Street. Facing you across the junction is the Grade II listed Viaduct Tavern – a fine example of a Victorian gin palace. Years ago, there were many hundreds of such gin palaces in London, but many have either been demolished or simply turned into more modern pubs. The story of gin and the gin palaces in London is fascinating, so once again I have written a little more in the appendix.

You can’t fail to notice the enormous, and to me slightly formidable, older building opposite you on the other side – The Old Bailey, Britain’s most famous criminal court. The building’s most conspicuous feature – it certainly catches the light and stands out from quite a distance away – is the 67-feet high copper dome on which sits a 22-ton, 12-feet high gilded bronze and gold leaf statue of the ‘Lady of Justice’, with the sword of retribution in one hand and a set of scales (representing justice) in the other. The dome is said to be a ‘miniature’ of the one atop St Paul’s Cathedral. The figure has to be cleaned twice a year and at 212 feet above the ground it can be a challenge for the cleaners, who of course aren’t able to use scaffolding.

Cross over now to take a closer look.

Just to help you get your bearings …. I’ll just add here that at the bottom of the Old Bailey (street) is Ludgate Circus – from there a two minutes’ walk up Ludgate Hill takes you to St Paul’s Cathedral.

![]()

The walk now continues down past the new Old Bailey building … at the end of it you’ll see the narrow Warwick Court – This is the rather hidden away and very non-descript entrance into the public galleries. (I’ve put more information in the appendix about how to get in.)

Carry on to the end of Warwick Court … go up the steps into Warwick Square then turn left into Warwick Lane. (If you were to turn right down Warwick Lane and left into Amen Court, you can see the original wall of Newgate Prison – but there’s nothing much to see.)

As soon as you turn left into Warwick Lane, you will see on your left an enormous pair of doors with a sign explaining this was the ‘Site of the Royal College of Physicians’ from 1674–1825. Next to it is Cutlers’ Hall, the lovely headquarters of the Worshipful Company of Cutlers, one of the oldest of London’s livery companies. It dates back to the late 13th century – and cutlers were the craftsmen who produced and traded items with a ‘cutting edge’ – such as swords and knives. I’ve put a little more about the Cutlers’ Company in the appendix.

Finish: Newgate Street |

When you reach the top of Warwick Lane you are back on Newgate Street – where the walk ends.

However, if you want to now visit St Paul’s, then carry to the right and continue to the end of Newgate Street. I don’t give any information about St Paul’s here – I think that’s fairly well covered elsewhere.

Equally, if you need tubes or buses, then I suggest you also turn to the right and walk down Newgate Street. St Paul’s underground station is on the Central line – and in addition there are numerous bus routes from here to many parts of London.

I hope you’ve enjoyed the walk. If you have any helpful comments, suggestions or criticisms, then I’d love to hear them!

And an odd fact … it was as the result of the King paying a visit here and noticing that the lawyers sat on sacks of wool, using them as cushions, saying the wooden seats were too hard on their bums. He apparently thought it was a great idea, and so the custom was introduced that lawyers would sit on the ‘wool sack’ whilst performing legal duties.

And an odd fact … it was as the result of the King paying a visit here and noticing that the lawyers sat on sacks of wool, using them as cushions, saying the wooden seats were too hard on their bums. He apparently thought it was a great idea, and so the custom was introduced that lawyers would sit on the ‘wool sack’ whilst performing legal duties.