Updated: 11 July 2024 |

|

Length: About 3 miles |

|

Duration: Around 4 hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

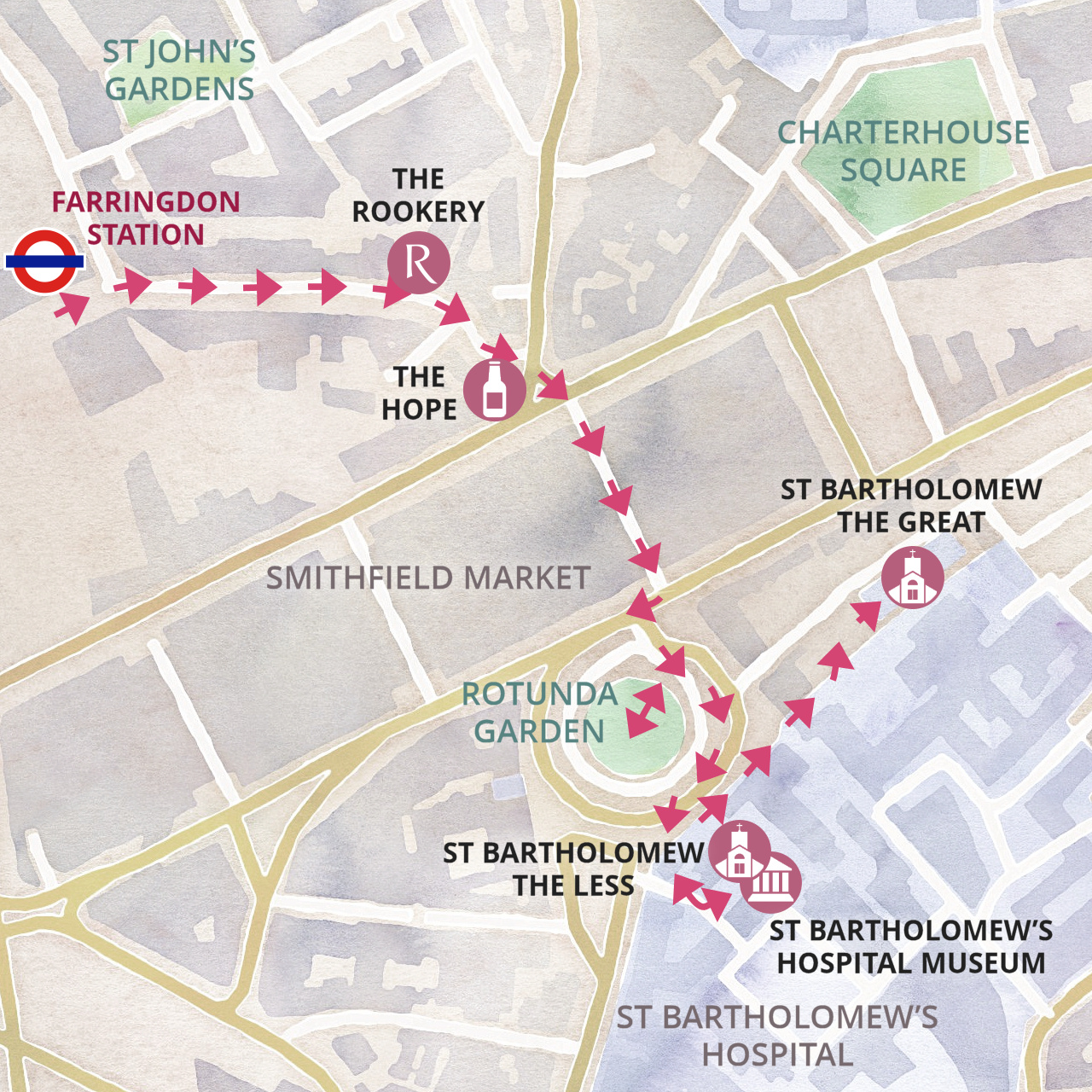

A walk from Farringdon to Clerkenwell

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WALK

Smithfield Market, St Bartholomew’s Hospital and churches, St John’s Gate and Priory Church, Clerkenwell Green, Charterhouse Priory and Museum, Exmouth Market, Mount Pleasant Postal Museum and the underground postal railway – Mail Rail.

Start: Farringdon station |

|

Finish: Exmouth Market |

GETTING HERE

The walk starts at Farringdon station, which is served by the Circle, Hammersmith & City and Elizabeth lines, as well as Thameslink mainline rail services.

If you are travelling by bus, the closest bus stop to the station is served by number 63 (from King’s Cross). Buses that stop within a five to ten-minute walk include the 17, 45 and 172.

CLERKENWELL – A BRIEF BACKGROUND

Clerkenwell developed from a hamlet serving the monasteries that had been established here from the 11th century. Lying outside of the City of London, it was free from the standards of behaviour and various restrictions that those living in the City were forced to abide by.

A description of Clerkenwell in the 16th century read, “there were a great number of dissolute, loose, and insolent people” … harboured in “noisome and disorderly houses, poor cottages, and habitations of beggars and people without trade … taverns, dicing houses, bowling alleys and brothel houses.”

During the 17th century many Huguenots, escaping from religious persecution in northern Europe, settled in Clerkenwell and brought with them their highly specialised skills, such as clock and watchmaking, for which the area had become well known by the early 18th century.

Clerkenwell’s proximity to the City of London and its good water supplies meant that it grew rapidly, particularly in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and this resulted in it becoming extremely overcrowded and subsequently infamous for its slums and levels of crime.

It also became known for its radical and revolutionary politics. John Wilkes, an 18th century ‘defender of free speech’, lived near Clerkenwell Green, as many years later did Lenin. And it’s still home to the Marx Memorial Library, which we see on the walk.

I have put a fuller version of this background in the appendix.

STARTING THE WALK

Please note – there are two stations entrances at Farringdon, facing each other across Cowcross Street, as well as a new entrance at the north end of the original station, on Turnmill Street. (There’s also a pair of Elizabeth line entrances nearly 500 yards away on Long Lane, which I’ll point out a little later in the walk.) Assuming you emerge from the old station building, or are at least standing with your back to it, then turn left along Cowcross Street.

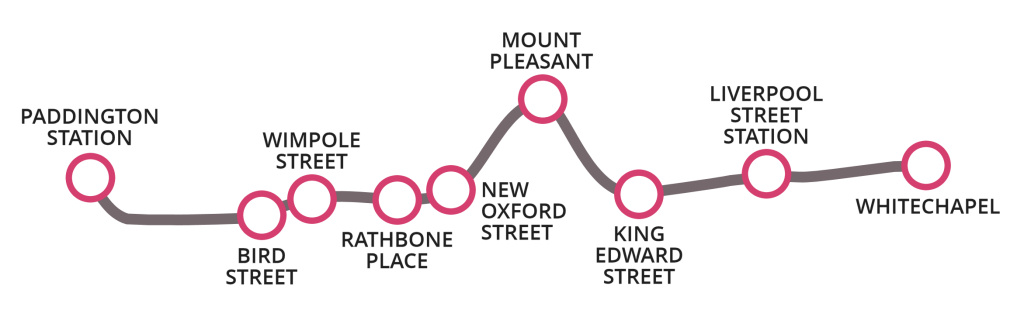

As you do so, look back up at the façade of the underground station where engraved into the stone work above the entrance it says, ‘Farringdon and High Holborn Station’ and adds ‘Metropolitan Railway’. This was once the terminus of the first underground line in London – and indeed the world – and it opened in 1863. The other end of the line was Paddington, and the stations it called at then are those the Circle and Hammersmith & City Line pass through today.

After 50 yards, fork right to continue up Cowcross Street, so named because cows did literally cross over here on route to the nearby market (more about this in the section on Smithfield Market). It is now a street of bars, fast-food outlets and restaurants – and although the Three Compasses Inn that you pass on your right has been here since 1723, it has clearly been modernised since then.

As you approach the bend at the top of Cowcross Street on the left you pass a row of six 18th century houses, which had shops on the ground floor and living accommodation above them. You can just about make out some of the trades – a pork butcher, confectioner and a dairy – from the signs on the fascia above, although they are now somewhat faded. Although you wouldn’t know it from here, the building is now a lovely ‘boutique’ hotel called The Rookery, with its entrance in Peter’s Lane, which runs alongside the building.

The name ‘rookery’ means both slum as well as ‘criminal area’ and this area had a terrible reputation for crime and violence. And seemingly the violence hasn’t completely disappeared – apparently it was in this hotel that Pete Doherty, lead singer of the Libertines and one-time boyfriend of model Kate Moss, beat up a filmmaker who was also staying here – and ended up in prison as a result.

Continue on to the top of Cowcross Street, passing the Hope Inn on the right.

Ahead of you is the impressive Smithfield Market – which will sadly soon be closing – after trading here for over six hundred years – and moving to a new purpose-built site in Essex.

I’ve written more about this and the market’s history here, and in the appendix.

Cross over Charterhouse Street and walk through Grand Avenue, which divides the two halves of the market.

The other end of Grand Avenue opens out into Long Lane, which we cross over at the traffic lights.

Once on the other side, take a look back at the market buildings – from this side you can get a better appreciation of their size and architecture. Notice the two domed turrets at each end that certainly help to give it such a classical look. They were only constructed in 1953, replacing wooden lantern-shaped structures that looked like Japanese pagodas, resulting in the General Market becoming known as the ‘Japanese Village’.

You can see the extent of the market buildings by looking further on down West Smithfield, which is where the new Museum of London will be. (If you want to walk down to take a look, then simply pick up the walk again here.)

Having crossed over Long Lane, you’ll see a little ‘garden park’ with railings around it. Look over the railings and you’ll see the circular roadway that leads to an underground car park; however, this was once an enormous storage area where cattle, and later the carcasses, were kept before being brought up on barrows and taken into the market to be sold.

At one time it also led to an underground railway station that was built under the market to accommodate the freight trains that brought in animals or meat from different parts of the country. Previously they were brought in by ‘drovers’, sometimes from hundreds of miles away. Now the cattle are slaughtered elsewhere and arrive by lorry. The railway is still there – at the far end of the carpark you can hear the trains rattling past as it’s now the Thameslink line that runs from Luton to Brighton, going underground after King’s Cross and emerging at London Bridge Station.

Walk into the garden and in the middle you’ll see a fountain and a statue – a popular place in fine weather for office workers to take their lunch.

Leave the garden the way you went in and follow the railings around to the right (in a clockwise direction) crossing over the entrance road that leads down into the carpark and when you are almost half way round look out for the magnificent Henry VIII Gateway you’ll see on the other side of the road that will take you into St Bartholomew’s (Barts) Hospital.

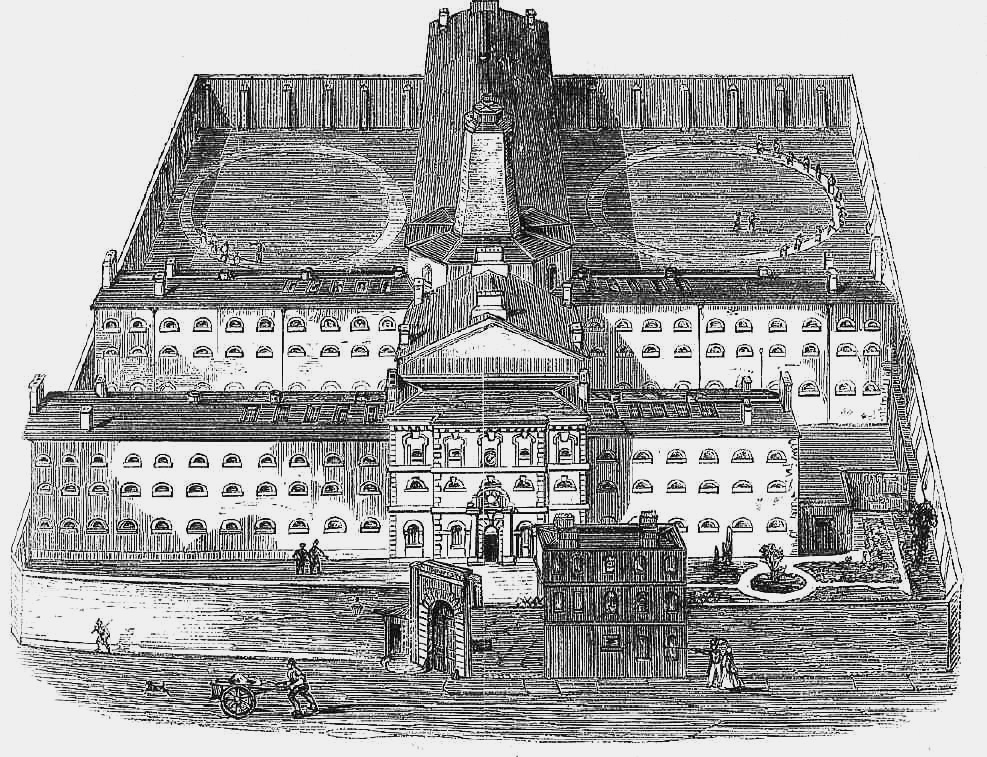

St Bartholomew’s is the oldest hospital in Britain. It opened in 1123 on a site given by Henry I and ‘devoted to the relief of pain and the cure of disease among the poor of London through the increase of knowledge in the medical art, here attained to the alleviation of human suffering throughout the world.’ However, during Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, he had the hospital closed. He later changed his mind and allowed it to be reopened, which is why there is a statue to him on top of the gateway, erected as a tribute to him for doing so. The gate was rebuilt in 1702 as a gift from the stonemasons who had worked on St Paul’s Cathedral as some of those who’d been injured during its building were said to have been treated here.

St Bartholomew’s is regarded by many in the medical profession as England’s ‘premier hospital’, and it has played a major part in the improvement of standards of nursing care and of the working conditions for nurses. Two of the early matrons were largely responsible for this and I have put more information in the appendix about this.

Fortunately, the hospital survived both the Great Fire of London and the Blitz during the Second World War.

Once you’ve passed through the gateway, on your left is the Church of St Bartholomew the Less. It’s open every day and certainly worth taking a look inside.

Leave the church and turn left and under the archway just a few yards further on, is the Museum of St Bartholomew’s. It’s actually in the hospital’s historic North Wing and overlooks the famous 18th century square. Open from Tuesday through to Saturday, it is free to enter and definitely worth visiting.

After leaving the museum turn left and just a few yards further on you can see the hospital’s magnificent central square.

Then turn around and walk back the way you have just come, pass out through the entrance archway and turn to the right walking back up alongside the hospital.

In front of you will be an Elizabethan half-timbered building under which is an archway that leads you next into the entrance of St Bartholomew the Great.

Leave the church the way you came in and turn right, then right again into Cloth Fair, a rather ancient street that has been reasonably well preserved. As you walk past the church you can see how large it actually is; and what is interesting is how much lower than the surrounding ground the older part at the rear is compared with the rest.

In the 15th and early 16th centuries, the annual Cloth Fair, one of the biggest cloth markets in Europe, was held here on St Bartholomew’s Day.

Take a look at No.41 Cloth Fair; the colourful panels beneath the windows date back to 1647 and, together with the church opposite, are among the few remaining buildings that survived both the Great Fire and the Blitz.

Just along, at number 38, is the Rising Sun, an 18th century pub that was once the haunt of an infamous gang of body snatchers. They would drug drunken strangers and sell their bodies to the doctors and students at the nearby St Bartholomew’s Hospital who were keen to practice and learn more about human anatomy.

Next on the right after the church is the Hand & Shears Inn – the sign on the wall outside says, “Last Ale before Newgate Public Execution”. Nicknamed the ‘Fist and Clippers’ by locals, it used to be popular with the cloth merchants. Established in 1532 and rebuilt around 1850, it still has a very old-fashioned feel inside with dark wood partitions and if it’s open then perhaps take a look. It was from the pub’s doorway that Lord Mayors of London would declare when Bartholomew Fair was open. The pub was also used as the unofficial ‘court’ where licences for those wishing to trade at the fair would be granted and where the weights and measures they used would be checked for accuracy.

We leave Cloth Fair here, so turn left opposite the Hand & Shears, and after just a few yards you’ll see another very old Smithfield tavern – The Old Red Cow. A sign on the wall explains that a previous landlord entertained many personalities of stage and screen here, including the likes of Peter Ustinov and Bernard Miles.

The inn is on the corner of Long Lane which we turn left into but then after only about 50 yards cross over and turn right down Lindsey Street, (with the eastern side of the market on your left.) On your right is the eastern entrance to Farringdon’s Elizabeth line station, within the ground floor of a new office building called Kaleidoscope.

After just 50 yards or so, turn right into Charterhouse Street and after around 100 yards you come to the historic Charterhouse Square. Walk to the far end of the square and turn left down the side of the gardens – as you do so look out for the art deco building on your right called Florin Court; you may recognise it as Whitehaven Mansions, where Hercule Poirot lived, or at least did in the television series. Built in 1927 by architects who previously had worked for Edwin Lutyens, it is now Grade II listed. Its rather unusual ‘U’ shape was carefully chosen to allow as many apartments as possible to overlook the square. And with a roof garden, Jacuzzis and basement swimming pool it must be a rather nice place to live.

I like Charterhouse Square. Despite all the changes, demolitions and renovations over the years, the northern side of it still seems to retain the feel of a ‘cathedral close’ in one of England’s smaller cities.

At the bottom of the short road on the eastern side of the square is the entrance into the Queen Mary University campus and the Barts and London School of Medicine and Dentistry, but we turn left along the north side, past three well-preserved townhouses. The one on the left was until recently an excellent café called ‘14 on the Green’ – there may be a new café here by the time you pass by.

Next to it is the entrance to the ancient Charterhouse Priory. It has a museum which is free to enter and certainly interesting and worth a visit if you have time. There’ also an excellent gift shop – and of course the all-important toilets. You can also visit the ancient cloisters, with its magnificent ceiling. It’s open Tuesdays through to Sundays from 11am to 4.45pm.

Time to stop for a meal?

Named in honour of Smithfield Market, Le Café du Marché was founded in 1986 in premises that had once been a coach house for the neighbouring Charterhouse. Its French cuisine is delicious – but pricy.

Time to stop for a meal?

Named in honour of Smithfield Market, Le Café du Marché was founded in 1986 in premises that had once been a coach house for the neighbouring Charterhouse. Its French cuisine is delicious – but pricy.

Leave the priory and turn right, passing its original small, gated entrance, passing out through the iron gates and past the Malmaison Hotel. It might be considered a strange name for a hotel as in French it means ‘bad house’, but having stayed there I can recommend it. It opened in 1856 as the Cocker’s Hotel, later becoming known as the Charterhouse Hotel. For a while it was then used for accommodation for nurses working at the nearby St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Pass the short passageway that leads to the delightful (and expensive) Café du Marché French restaurant and then you pass the attractive looking Fox & Anchor Inn that opened in 1893 – look up and notice its lovely Art Nouveau façade. A few doors along there’s another old pub, the Smithfield Tavern, which was rebuilt in 1871.

When you reach the next corner, you’ll realise we’ve done a ‘circle’ as you are now back to where we started before entering Smithfield Market.

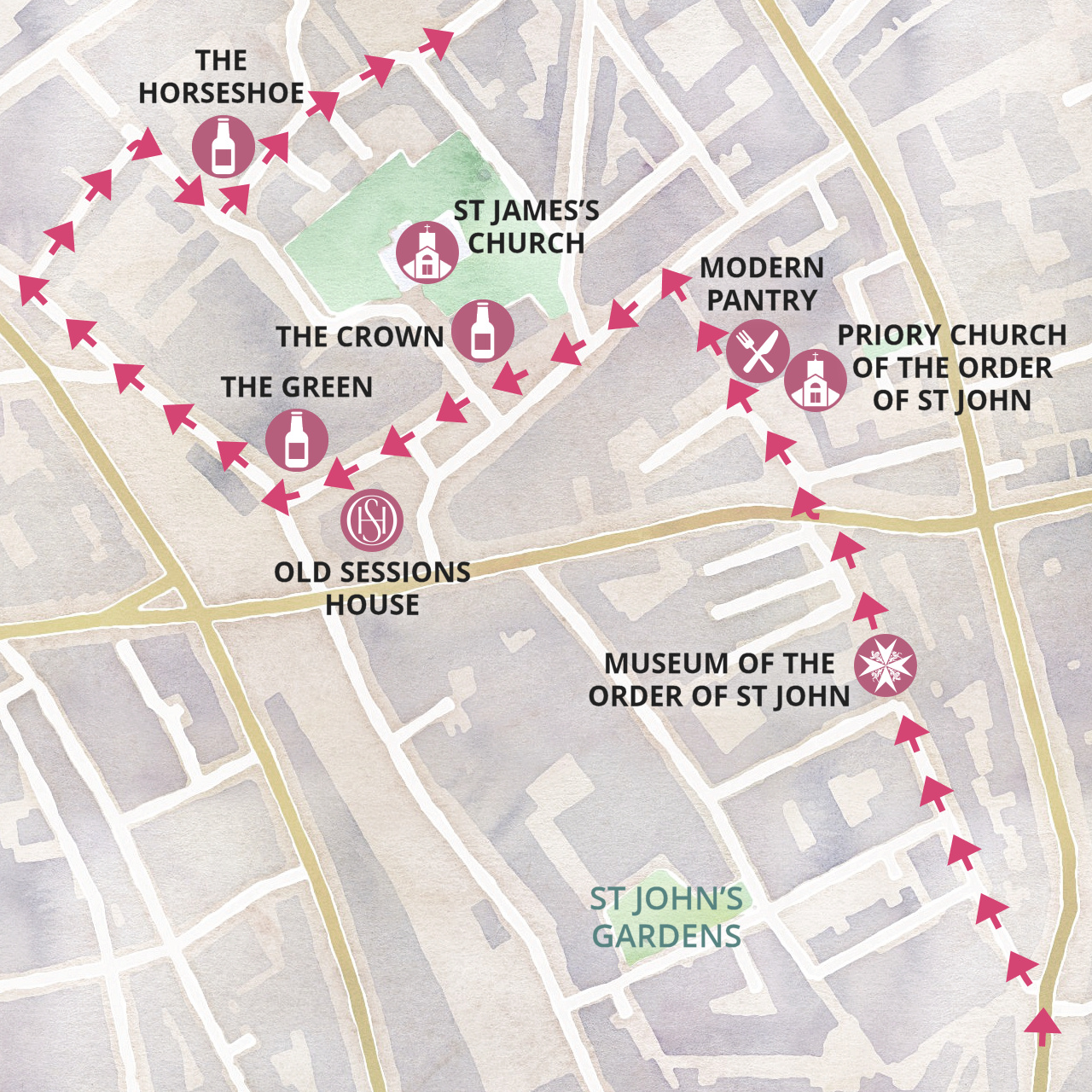

Turn right up St John’s Street, passing the top of Cowcross Street and continue straight ahead for a couple of hundred yards. Where the road divides, cross over and take the narrower, left hand fork up St John’s Lane (the wider St John’s Street carries on up to the right).

On the right you pass the modern Watchmaker Court, which is presumably on the site of various watchmakers’ businesses as there are a number of names of such craftsmen carved into the wall of the building. (In the 17th and 18th centuries Clerkenwell was a centre of the watch and clockmaking industry.)

A sign on the wall of No. 28 explains the building was partly destroyed by German aircraft in the First World War – unusually not the Second. And next to it notice the narrow Passing Alley. Around 200 years ago maps showed it being called ‘Pissing Alley’, apparently on account of it being used for that purpose!

You’ve now arrived at the historic St John’s Gate, the South Gate entrance of the enormous Clerkenwell Priory that once covered an area of over six acres. The priory was closed following the dissolution of the monasteries and whilst much of it was eventually demolished, St John’s Gate survived, and now houses the Museum of the Order of St John.

The museum is free to enter and although small, is well worth a short visit. It tells the story of the Venerable Order of St John, from its origin as the ‘pan-European’ Order of Hospitaller Knights that was founded in Jerusalem during the Crusades, right through to today’s St John’s Ambulance Corps, whose volunteers give up their time to provide emergency first aid help at public events across the country.

Whilst visitors to the museum aren’t able to see the other parts of the building, these can be seen on one of the excellent regular daily tours that include the magnificent Chapter Hall and Council Chamber.

Continue on through the archway. Sadly you’re now confronted with an awful mismatch of modern buildings – the one on the left at No.1 St John’s Square is to my mind particularly out of keeping and just plain ugly.

You can get some idea of how large the priory once was as St John’s Square, which you are now in, extends ahead as far as you can see, though since the 1870s it’s been dissected by Clerkenwell Road.

Cross over Clerkenwell Road (I suggest you use the little traffic island as it’s a busy road) and walk up on the right-hand side of the square. The large brick building on your left is the Zetter Hotel – and a point of interest to older readers who may remember Zetter Pools, this was their headquarters.

On your right you will see the fairly modern brick-built Priory Church of the Order of St John, to my mind looking more like a local government office than a church. It had been destroyed during the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt and eventually rebuilt, but then destroyed again during a bombing raid in the Second World War, being rebuilt in its present form in 1960.

If you stand outside the front of the church you can see the outline of the original circular nave, marked by a line of different coloured stones in the ground. The design was based on that of the Holy Sepulchre Church in Jerusalem, as is the other Knights Templar church that still stands in the Temple grounds, south of Fleet Street.

The 12th century crypt, which wasn’t damaged on either occasion, was at one time used to store dead bodies, but these were removed in the late 19th century when the crypt was restored. It is now only open for pre-booked tours or by special arrangement.

If you walk into the entrance porch of the church, you can see the lovely priory memorial garden, which was established in 1958 whilst the church was being restored. The garden is planted with medicinal herbs, including many used in patient care in the order’s medieval hospitals. As previously explained, the order’s historic caring role and medical heritage are the foundations of its current charitable work through both St John Ambulance and the St John’s Eye Hospital, in Jerusalem.

After leaving the priory church, continue to the top of the square. The walk continues up the narrow Jerusalem Passage that runs up the left-hand side of the red brick Modern Pantry restaurant that faces you. (Jerusalem Passage was once the northern entrance to the Clerkenwell Priory, which again gives you an idea of its size.)

Before you walk up Jerusalem Passage, notice on the left at the bottom what looks like a private house – however, a small sign on the door explains it is the Zetter Hotel Town House. Look in the windows and you will see a cosy room with comfy chairs. Even better, pop inside and you’ll find one of London’s most delightful little bars. It’s more like the sitting room of a country house. It’s open to the public as well as residents, so if you can find somewhere to sit, maybe enjoy a coffee (or something stronger).

Walk to the top of Jerusalem Passage, past the Belgian bar that sells beer and mussels, and at the top turn left into Aylesbury Street. A rather interesting gentleman used to live in the house on the corner. His name was Thomas Britton, who was both a coal merchant and book seller and in his long and somewhat narrow loft (apparently reached by an outside staircase) he used to stage musical evenings, even having Handel himself playing there on more than one occasion. Despite the unattractive surroundings, these concerts were extremely popular and ran for forty years until his death in 1714.

After 50 yards or so the street sign tells you it has now become Clerkenwell Green. Cross over to the right-hand side and if you look up to your right you can see the surprisingly large churchyard of St James (take a look if you aren’t in a hurry, though the entrance to the church is just a little further along and we see it shortly).

Continue on until you come to the Crown Tavern, said to be where Stalin and Lenin first met in 1905.

Running up the side of the pub is Clerkenwell Close, where you can see St James’s Church. The original church dated back to 1540, though it was rebuilt in 1792. It is an interesting church so if you have time it’s possibly worth a little look inside. However, with such steep steps leading up to the front door, it clearly wasn’t designed with any thought for possible disabled or infirm churchgoers.

Having crossed over Clerkenwell Close, look out for No. 37A in the next row of buildings. There had been a Welsh school close by since around 1718, and in 1738 it moved into new buildings at No.37A Clerkenwell Green.

The Welsh School had been established to assist the children of poor parents of Welsh parentage who lived in and around London. It was initially just for boys, many of whom were trained for apprenticeships, but later girls were also admitted. Some years later the school moved to Ashford in Middlesex, where it is now called the St David’s School for Girls.

However, its building then became the offices of various socialist organisations and a printing press was installed to enable them to produce their literature. As an example, by 1902 they were printing Lenin’s Russian Social Democratic newspaper. A library, with a wide selection of socialist books, was opened and Marx spent a considerable amount of time reading and studying here. Indeed, in 1933 it became the Marx Memorial Library, founded with the aim of advancing education and knowledge of all aspects of the ‘science of Marxism, the history of socialism and the working-class movement’. The Library is still here and is open Mondays through to Thursday from noon until 4pm. Guided tours of the building are available on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 1pm, when you can visit the historic vaults and see the room where Lenin worked in exile from 1902–3.

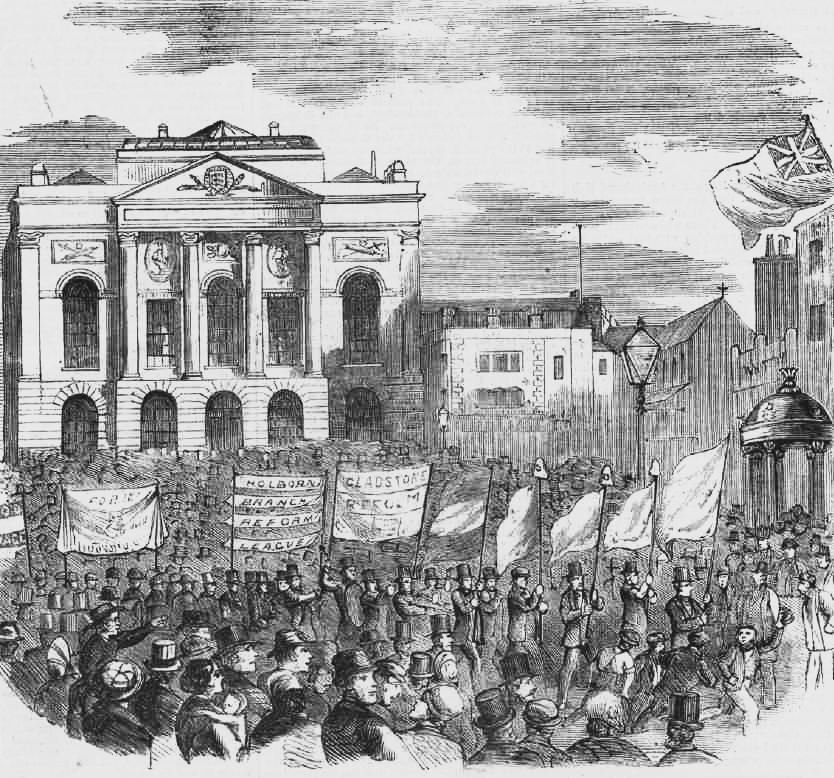

The Old Sessions House

The large and grand building on the left at the bottom of the square was once the Court House of the Middlesex Sessions.

The court house was built around 1780 in what was regarded as a ‘classical Palladian style’ and the magnificent dome that covers the entrance hall and staircase is modelled on the Pantheon in Rome. The jurisdiction of the court was extensive, and it was said to have been one of the busiest courts in Britain.

It continued as a courthouse until 1921 when the building then became the headquarters of the Avery Weighing Machine Company. They left in 1973 and the building was empty for a few years until it was restored as a masonic conference centre. Apparently, a couple of years ago there were plans for it to have been become a bar and restaurant or even a private members’ club, but instead it has been beautifully restored and the lower floors are the offices.

Continue down to the bottom of the road then turn to the right up Farringdon Lane. (To your left is Turnmill Lane which runs back down to Farringdon Station; its name a result of the watermills that were once here, powered by the River Fleet that runs under the adjacent Farringdon Road.)

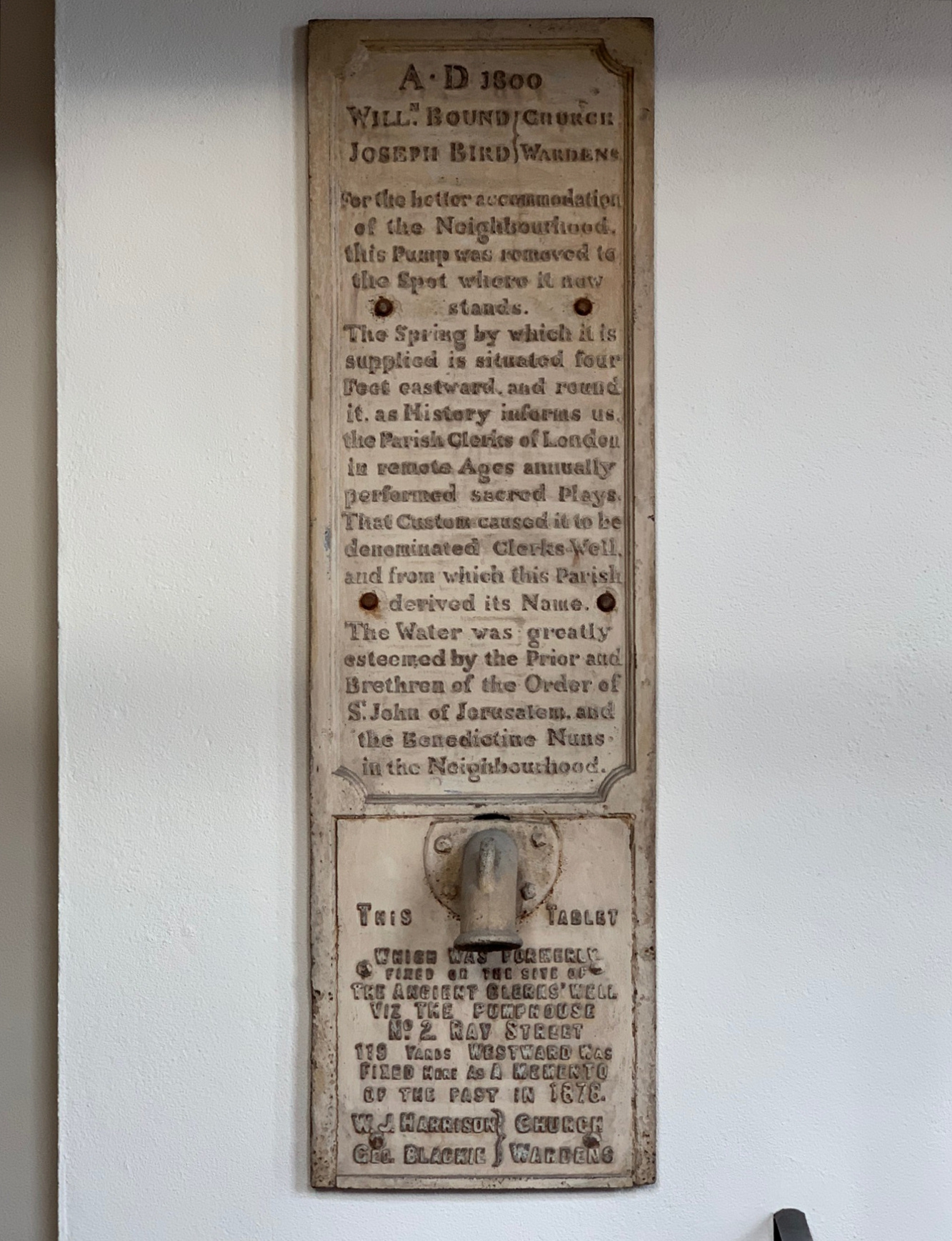

A few yards up Farringdon Lane, and just past the Green Pub on your right – look into the last window of the marble-clad building called Well Court and you can see the original Clerks’ Well.

The Clerks’ Well is an ancient water well that was rediscovered in 1924. It’s situated on the edge of the St Mary’s Benedictine Nunnery and was where the sisters obtained their water. But the clerks? They were the parish clerks who had become famous for the medieval miracle plays they performed in this area. The plays date back to the 15th and 16th centuries and depict scenes from the Bible that encouraged the audience to lead Christian lives. They were usually organised and funded by the guilds of craftsmen and merchants and at times were even watched by royalty.

Continue on a little further up Farringdon Lane until you reach the Betsey Trotwood pub, which is built directly on top of the railway lines coming out of Farringdon Station. (Betsey Trotwood was the name of a Dickens character in David Copperfield, but there doesn’t seem to be any connection with the pub. I guess they just preferred it to the previous name, which was the Butcher’s Arms.)

From here take a look across to the other side of Farringdon Road and notice the tall brick buildings, which were once workshops, small factories and warehouses. Fortunately many have been restored rather than be demolished and replaced with modern concrete and glass structures, as has happened too often. As a result, from being a ‘derelict area’ a few years ago, it has now become a fashionable and desirable place to live, and apartments in old industrial buildings like these are now very expensive.

To the right of the pub we turn right up Pear Tree Court. On the right-hand side are a number of large blocks of flats – these are part of a Peabody Trust housing estate, one of several in London that were built thanks to the generosity and vision of the American millionaire philanthropist George Peabody. The different coloured bricks certainly help make the otherwise austere looking blocks more attractive.

Walk to the top of Pear Tree Court and turn to the right – when you reach the Horseshoe pub turn immediately left up Clerkenwell Close (the road that carries on ahead is of the same name, so make sure you turn left up the side of the pub.)

All around you are some remarkably well-restored old warehouses and industrial buildings that have become trendy apartments.

At the top of Clerkenwell Close don’t follow the road to the left but go straight ahead up the narrower Sans Walk. (And just as a small point of interest, you may have noticed how Clerkenwell Close, which we originally saw a few minutes ago from Clerkenwell Green, follows a strange winding pattern – this is because it follows the outline of St Mary’s Nunnery, which was demolished in the 16th century).

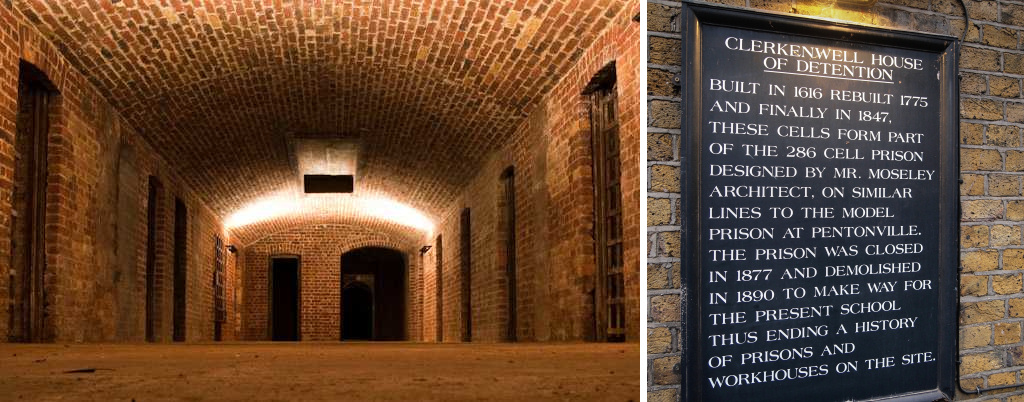

After 50 yards or so, you’ll see on your left a small wooden gate at the start of the brick wall – this is the entrance to the underground catacombs of the Clerkenwell House of Detention. Although the main prison was above ground – in a moment we see what’s been built on the site it occupied – there were many cells and chambers underground.

Continue ahead for a few more yards and you come to the building that has been built on the site of the prison. Originally a school, called the Hugh Myddleton School, it closed in the 1970s and the building was turned into apartments, known as Kingsway Place. Take a look through the entrance gates and you can see what a good job the developers appear to have made of this grand old school building.

Continue walking along Sans Walk. At the end a tiny sign high up on the wall on the right says, ‘This wall is the entire property of the County of Middlesex’ – a reminder that this area, like much of north London, was once part of that county.

Bear to the right, cross over Woodbridge Street and walk to the left around the railings of the house on the corner and turn up Sekforde Street. (Thomas Seckford, or Sekforde, was an Elizabethan ‘man of law’ who owned a large estate in this area.) I particularly like the style of the houses along this street, but halfway along notice the attractive building between Nos.18 and 19 with an inscription carved into the stone fascia that reads, ‘Finsbury Bank for Savings’. The bank had been set up in 1816 for ‘tradesmen, mechanics, labourers, servants and others’ and moved to these premises in 1840.

At the top, turn left into the busy St John Street and at the crossroads turn left into the wide Skinner Street.

Where the road bends, take the left fork at the traffic island and walk straight ahead into Corporation Row (there isn’t a street sign). On your right you’ll see Spa Fields, a two-acre park.

Spa Fields park was a pleasure ground in the 18th century. There were three bowling greens (nearby there is still a street named Bowling Green Lane), a bear garden, duck ponds and numerous pubs. But what had made this area popular was the Spa. Known as the ‘London Spa’, it opened after a local beer and wine merchant discovered (supposedly with the help of a scientist) that the waters in his well were the best of the local ‘medicinal iron waters’, with all sorts of health-giving properties. (The area was already beginning to be known for its ‘waters’, hence Sadler’s Wells and the Islington Spa.)

It has, however, a more sinister past. Click the button below to read about the Bone House.

Take the first right into Northampton Road. You’ll see the huge London Metropolitan Archives and Finsbury Business Centre on the left. It was formerly the Temple Press printing works but is now the largest public records office in Britain and the principal archive repository for the City of London and the Greater London area. They have 72 miles of shelves of archives dating as far back as 1067 and handle 30,000 visitors a year and an equal number of written enquiries. Just a few yards further on you pass the Bourne & Hollingsworth bar and restaurant – which I can certainly recommend.

At the top of the road walk straight ahead up the short pedestrianised lane through the Spa Fields Park, which as you will see has extensive and well-equipped children’s play areas – a wonderful facility for kids living in the tower blocks of the huge nearby Finsbury housing estate and, to its north, the smaller, pioneering Spa Green estate.

At the top, cross over Rosoman Place into Rosoman Street. Ahead is a junction of several roads. We’re going to walk on for just a few more yards then turn left into Exmouth Market.

This lively, semi-pedestrianised street had been a market for over a hundred years, but eventually it died out. The street had become rather run down but is now a very popular spot both during the day and evening thanks to the number of bars and restaurants that have opened, as well as several gift-type shops. Many of the bars and restaurants have outside seating, making it a particularly attractive place to visit in nice weather.

In addition, the market has now been reintroduced on weekdays, with many of the stalls selling street food, so becoming popular with local workers at lunchtimes.

Two-thirds of the way along the street you pass the Church of Our Most Holy Redeemer. I like it; it has an Italianate look and is one of a select few basilica-style churches in London.

If it’s open, take a look inside and you could easily believe it is a Catholic church; however, it’s actually Church of England, although known as ‘Anglo-Catholic’. This means it is within the catholic tradition of the Church of England and receives ‘alternate episcopal oversight’ from the Bishop of Fulham. (Episcopal oversight is commonly known as a ‘flying bishop’ – a Church of England bishop assigned to minister to those clergy and parishes that ‘are unable to receive the ministry of women bishops or priests’.)

Almost opposite the church is a pub called the Exmouth Arms. The street was originally called Baynes Row, but in 1939 was renamed after the pub.

At the end of the street is Farringdon Road. If you look diagonally to the right across this busy junction, you can see the Mount Pleasant Royal Mail Sorting Office, the world’s biggest postal sorting office, which opened in 1889 and was built on the site of the Coldbath Fields Prison. The reason the area had become known as Coldbath Fields was because ‘cold baths’ were actually established here around 1690 for the cure of rheumatism, convulsions and other nervous disorders. Then in 1794 the Middlesex House of Correction opened. It was said at the time to have been the largest prison in the country. It soon became more commonly known as the Coldbath Fields Prison.

And the name ‘Mount Pleasant’? That came later and was given to these fields with ironic intent after local people had begun to dump their refuse in them.

The Royal Mail site is huge, covering around nine acres, six of which were sold off to private developers in 2017 for £193 million. Plans were submitted to build 681 apartments and houses, as well as office and retail shops on the site but as a result of objections from local residents the proposal was rejected by the local authority. However, it went to appeal and controversially the plans were passed by Boris Johnson when he was Mayor of London.

The Royal Mail still use part of the remaining site for sorting mail. In addition, an an independent charitable trust has opened a Postal Museum that features a short ride on the now disused Post Office railway.

Finish: Exmouth Market |

We’re at the end of the walk.

To get back to central London – there’s a bus stop on the triangle at the end of the street and details of the buses from there are:

Number 19 – takes you to Cambridge Circus, Piccadilly Circus, Hyde Park Corner, and terminating south of the river in Battersea.

Number 38 – takes you to Gray’s Inn Road, Cambridge Circus, Piccadilly Circus and terminating at Victoria.

Number 63 – takes you to Farringdon Station, Newgate Street (Old Bailey/City Thames Link station), Blackfriars.

Number 341 – takes you to Holborn, Aldwych (Somerset House) and Waterloo.

Unfortunately, the nearest tube station is back at Farringdon – and to get there it’s a 12–15-minute walk (just under half a mile) down Farringdon Street, which is to your immediate left.

Although you have probably had enough walking for one day, there is a separate walk on the website that starts from Exmouth Market and finishes at the Angel Islington.