Updated: 17 October 2023 |

|

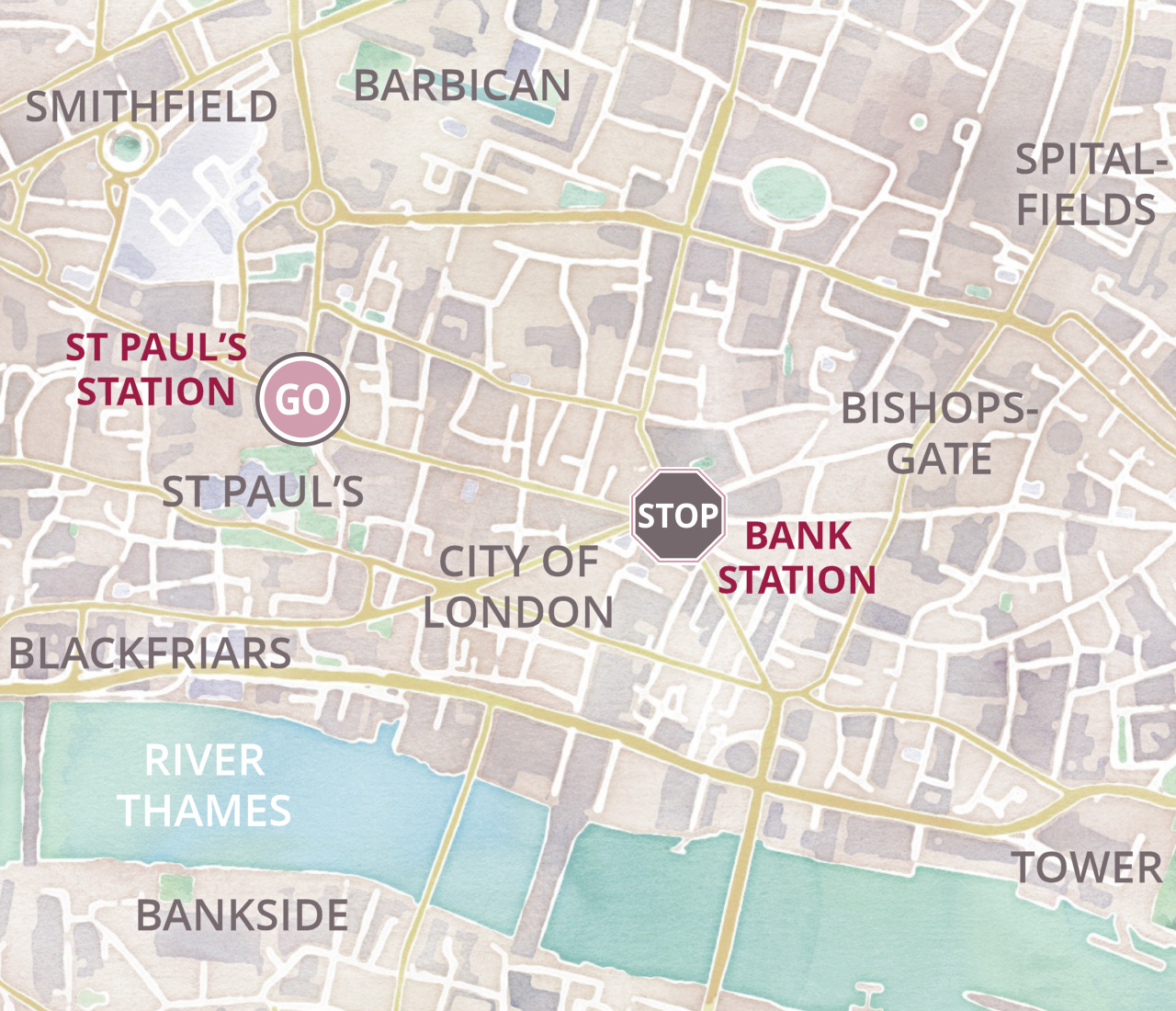

Length: About 3¼ miles |

|

Duration: Around 4 hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

City of London walk 2

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WALK

Cheapside, St Mary-le-Bow, Bow Lane, Watling Street, St Mary Aldermary, No 1 Poultry, St Stephen’s Walbrook, The Mansion House, The Royal Exchange, The Bank of England, Jamaica Wine House, Leadenhall Market, Lloyd’s of London, The ‘Scalpel’, The ‘Cheesegrater’, St Mary Axe, The ‘Gherkin’, The Baltic Exchange, Bishopsgate, The Heron Tower, Church of St Ethelburga the Virgin, Gibson Hall, Austin Friars, Dutch Church, Halls of the Worshipful Companies of Leathersellers, Carpenters and Drapers.

Start: St Paul’s station |

|

Finish: Bank station |

GETTING HERE

The walk starts in Cheapside, just a few hundred yards east of St Paul’s Cathedral.

The nearest tube station is St Paul’s, which is on the Central line.

There are numerous bus routes that serve the St Paul’s and Bank area.

Arriving by tube, leave the station at Exit 1 – it’s marked Cheapside – walk straight ahead, then bear slightly to your left. You will then be in Cheapside.

AN INTRODUCTION TO CHEAPSIDE

Cheapside had been the City’s main shopping street since the 12th century. ‘Cheap’ comes from the old English word ‘chepe’, meaning to barter, or a market where goods could be bartered for. Indeed, the names of several of the streets that lead off Cheapside come from the goods that were once sold here – Poultry, Bread Street, Milk Street, Honey Lane, Wood Street, Goldsmith Street, etc.

Following the Great Fire of London in 1666, Cheapside was rebuilt, and the market traders were moved to more permanent premises. Further changes took place after World War II when bombing had destroyed over half of its buildings. Over the past few years, the street has once again become the City of London’s main shopping street.

Since medieval times, Cheapside has also been part of the main ceremonial route from the Tower of London to Westminster and it’s still used today for events such as Royal coronations, funerals, processions and the Lord Mayor’s Show. The latter was something that started in 1215 and still takes place on the second Saturday of November. The Lord Mayor travels with the procession, which terminates just outside the City at the Royal Courts of Justice, where having been blessed at St Paul’s Cathedral, he swears an oath of allegiance to the Crown.

Charles Dickens’ son wrote about Cheapside in his 1879 Dictionary of London: “Cheapside remains now what it was five centuries ago, the greatest thoroughfare in the City of London. Other localities have had their day, have risen, become fashionable and have sunk into obscurity and neglect, but Cheapside has maintained its place and may boast of being the busiest thoroughfare in the world, with the sole exception perhaps of London-bridge.”

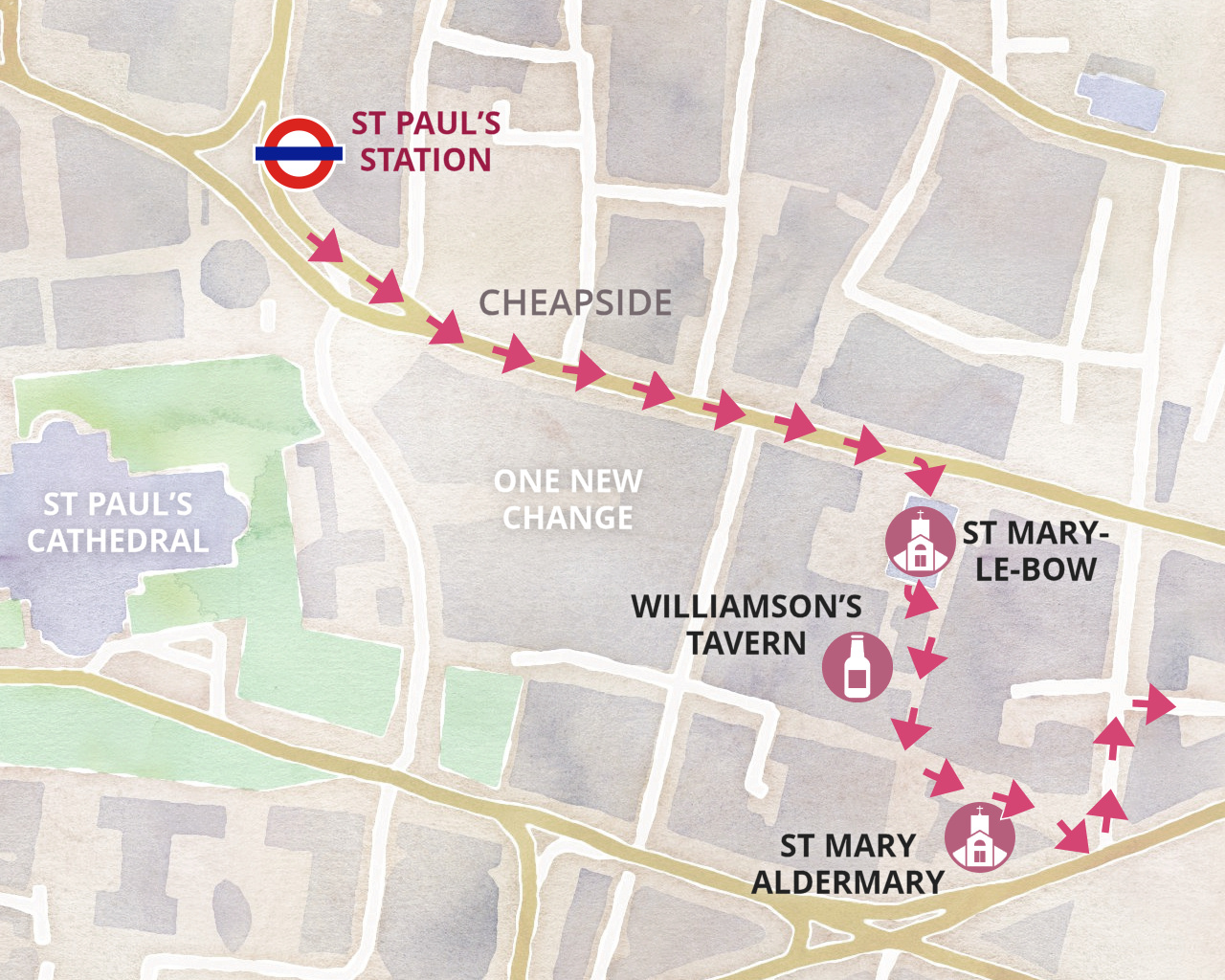

STARTING THE WALK

Walk down Cheapside on the left-hand side; on the right you’ll see the huge One New Change shopping centre that opened in 2010. It’s the largest shopping centre in the City of London and includes interesting roof terraces which, besides having a restaurant and bar, both with outdoor seating, offers public areas with an unusual view of St Paul’s Cathedral.

On the left side of the road is Wood Street; notice the ‘Cards Galore’ shop on the corner. It occupies one of the last remaining old buildings in Cheapside and is also a rare example of the two-storey buildings that were given permission to be built following the Great Fire of London in 1666. Just a few yards up Wood Street, virtually next to the shop, you’ll see a tiny ‘garden’ that now occupies what was once the churchyard of ‘St Peter Cheap’. The church had been built in 1196 but destroyed in the Great Fire of London and never rebuilt. It was in this churchyard that in 1791, William Wordsworth once stood and listened to a bird singing in the tree (I doubt it’s the tree that’s still there today!) Here he wrote the poem entitled ‘The Reverie of Poor Susan’, telling the story of the memories awakened in a country girl in London on hearing a thrush sing in the early morning. The first verse is as follows, but I have put the whole of the poem in the appendix.

The Reverie of Poor Susan

At the corner of Wood Street, when daylight appears,

Hangs a Thrush that sings loud, it has sung for three years:

Poor Susan has pass’d by the spot, and has heard

In the silence of morning the song of the bird.

As a point of general interest, I’ll also mention here that Wood Street is one of a number of streets in the City where it can sometimes be difficult to find a building with a number on. This is because many numbers were removed at the height of the IRA bombing campaign to make it more difficult for anyone planting a bomb to identify particular targets. In any case, the order of some numbers hasn’t always made sense since the Second World War – as a result of the intensive bombing raids on the City, some streets were left with hardly a building still standing. However, when redevelopment began, buildings weren’t necessarily erected in any particular order. So, sometimes one would be constructed in the middle of a street, with no other buildings around it, so it might have been numbered ‘1’- hence in some streets the building numbers can be quite haphazard. As a City of London policeman I had stopped to ask for help in finding an address told me, “It can be a nightmare for us and the other emergency services!”

Continue on down Cheapside – ahead of you on the other side, you’ve probably already noticed St Mary-le-Bow Church. It is Grade I listed and regarded as being one of the more beautiful churches in London. Built above ground level and with a flight of steps leading up to the entrance, as well as having a dramatic spire, it has always been a landmark and must have been an imposing sight in the days before tall buildings were erected.

Leave the church and walk through the adjacent Bow Churchyard.

The statue in the middle of the churchyard square is of Captain John Smith, who was born in Lancashire in 1580 and later became a member of this church.

Walk to the back of Bow Churchyard and follow the lane around the rear of the church – (the lane is also called ‘Bow Churchyard’) and then turn right down Bow Lane. This little pedestrianised street is usually packed with office workers at weekday lunch times and in the early evening. Thursdays and Fridays are particularly busy with the traditional City workers enjoying after-work drinks, and the numerous pubs and wine bars are not only full inside, but so is the street outside.

At one time there was an assortment of interesting little shops here, and whilst some have been replaced with fast food outlets, cafes and bars, a surprising number have survived. One of these is Rigby & Peller, the former supplier of the Queen’s undergarments. I say former because the shop’s founder lost their Royal Warrant because she had allegedly written too much detail in her autobiography about her visits to the palace to measure Her Majesty for her undergarments. Presumably Her Majesty has gone back to M&S!

As you walk down Bow Lane, look carefully for a small passage on the right called Groveland Court – it’s just before Rand and opposite Rigby & Peller and easy to miss but worth walking down to take a look.

Continue down Bow Lane, turning left when you reach the junction with Watling Street – (look to the right when you get there as there’s a lovely view of St Paul’s). On the opposite corner of Watling Street and Bow Lane is a pub called Ye Olde Watling. It is said to have been built by Sir Christopher Wren, using planks of brine-pickled timber from dismantled ships, to provide accommodation for the workers rebuilding St Paul’s Cathedral following the Great Fire of London.

Watling Street is an ancient route used for several thousand years by travellers going between Canterbury in Kent and St Albans in Hertfordshire. It crossed the River Thames by a ford close to Westminster Abbey. Formerly just a track to the coastal ports of Kent, the Romans both extended and paved it, so making it easier for their armies to move around. They eventually extended it northwards as far as Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland.

Having turned left down Watling Street, you’ll see on the right the side entrance to St Mary Aldermary. (There is sometimes a sign saying, ‘please use other door’, but if it is open, use this one to go in.)

Back outside the church you pass a sculpture that was created in honour of the cordwainer. So what is a cordwainer? Well, the word is an anglicisation of the French word ‘cordonnier’, which means shoemaker. It was introduced to England after the Norman invasion in 1066. However, it didn’t apply to an ordinary shoemaker, but only to a highly skilled craftsman who would have used the finest goatskin leather from Cordoba in southern Spain to make the finest shoes. The cordwainers’ roots in the City go back to 1272, and then in 1439 they were issued their royal charter, which enabled them to control the entire shoe trade within the City of London.

And the difference between a cordwainer and a cobbler? The latter weren’t allowed to make new shoes – just repair them. And the Cordwainers are the only historic trade body to have a ward (a district) of the City of London named after them, which is where you are now.

At the bottom of Watling Street, turn left and then left again up Queen Street – cross over, then turn right down Pancras Lane. The little ‘garden’ you pass on the left is the site of St Pancras Church, which was destroyed in the Great Fire in 1666. At the bottom of the lane, notice the wall plaque that explains it was the site of the parish church of St Benet Sherehog, yet another church destroyed in the Great Fire. The first recorded mention of this church is in the year 1111. And the unusual name ‘Sherehog’? It comes from the fact that in medieval times, this was one of the wool-dealing districts of London. And ‘sherehog’ was the name given to a castrated ram after its first shearing. Bet you didn’t know that – and if it ever comes up in a pub quiz, you could be a winner!

Turn left back along Queen Victoria Street – when you reach Bucklersbury Passage we’re going to cross over, but before we do just take a look into the ‘Passage’ under the enormous building on your left (called Number One Poultry).

Notice the two lifts on either side of the entrance into building. These go up to the roof where there’s the lovely Coq d’Argent French restaurant, brassiere and cocktail bar. Providing you’re moderately well-dressed then take the lift up to have a look. Besides the posh restaurant, there are terraced gardens with outdoor heaters, so you can enjoy an alfresco drink, lunch or dinner whatever the weather. Sometimes you are met as you step out of the lift – if you are, simply say you’re thinking of coming back for an evening cocktail or dinner and want to take a look first. They will then happily let you look around.

(And, if you did want to spoil yourself, they do an excellent 2-course set menu – with four choices for each course – for under £30 – three courses for £34. Per person of course – and that’s 2019 prices.)

Back to the walk. Cross over Queen Victoria Street and walk down the pedestrianised Bucklersbury, between the enormous Bloomberg building on the right and the totally different, tiny by comparison and lovely Victorian Number 1 Queen Victoria Street, which is the City of London Magistrates Court.

The Bloomberg building opened in 2017 and is the European headquarters of the giant American company of that name. It’s quite a staggering building, both in size (over 4,000 employees work here) and in its ‘sustainability’ – rainwater collected on the roof is used to flush the toilets for example. However, it was criticised for its ‘wasteful construction’. Apparently, 600 tons of Japanese bronze and 10,000 tons of Indian granite were used, all of which were obviously imported. And the interesting water feature in front of the building is meant to ‘evoke the Walbrook River’, which once flowed close by here.

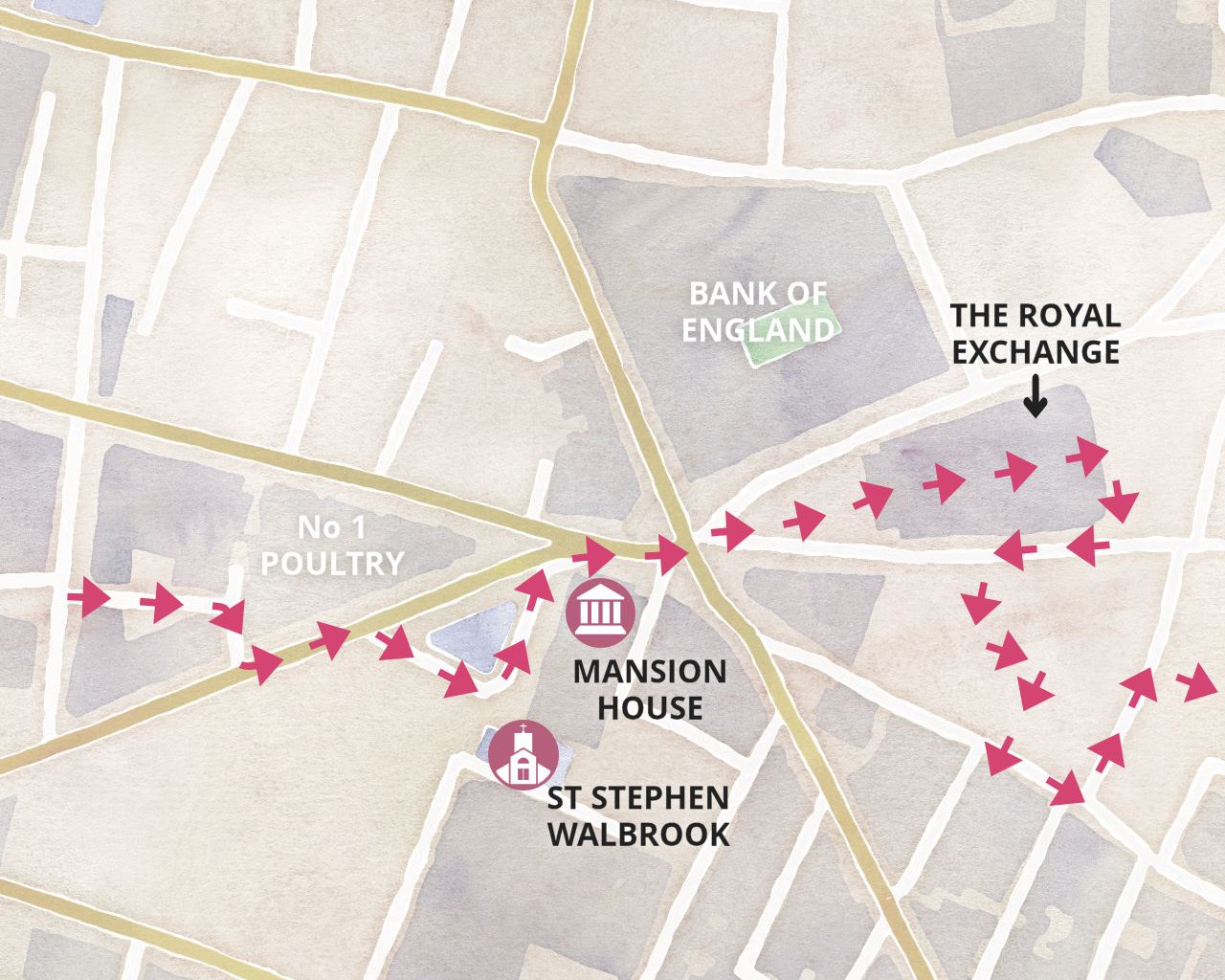

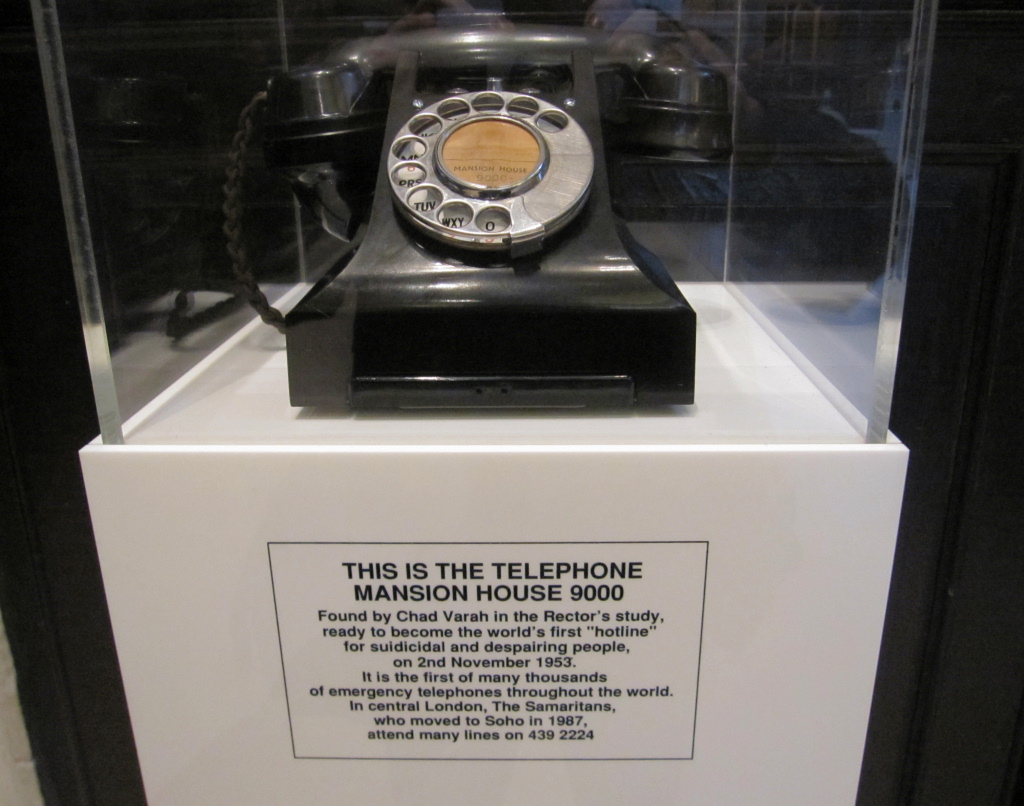

Facing you now is the wonderful parish church of St Stephen Walbrook. As the list of rectors inside shows, there has been a church here since 1301. Following its destruction in the Great Fire, it was the first church that Sir Christopher Wren rebuilt after the Great Fire. The splendid dome is modelled on his original design for the dome on St Paul’s Cathedral.

The church has an unusual shape being built using the ‘Greek cross form’ – and being ‘in the round’ means everyone is within 30 feet of the pulpit, which itself is a huge block of stone, designed by Henry Moore and controversial at the time. It’s very simple and very beautiful and it’s hardly surprising that it’s Grade l listed. Indeed, the renowned architectural author Sir Nicholas Pevsner said of the interior that it was “one of the ten most important buildings in England”. It’s definitely worth going in to take a look, not least to learn more about the church’s connection with the Samaritans, the emotional support helpline.

Turn right out of the church – and right again into St Stephen’s Row – the large building that backs onto the other side of the lane is the Mansion House – we see more of it in just a moment.

Behind the church is its little churchyard, now dwarfed by the huge modern offices of Rothschild’s, the banking conglomerate that was founded in 1761 and said to be one of the world’s wealthiest companies.

Turn left up Mansion House Place, which runs up the side of the Mansion House and at the top is one of the busiest junctions in central London – (or rather would have been until fairly recently when the City Corporation decided to make it ‘bus and cycle’ only and banned private cars and taxis). But first, take a few steps to the left to take a closer look at the Mansion House itself.

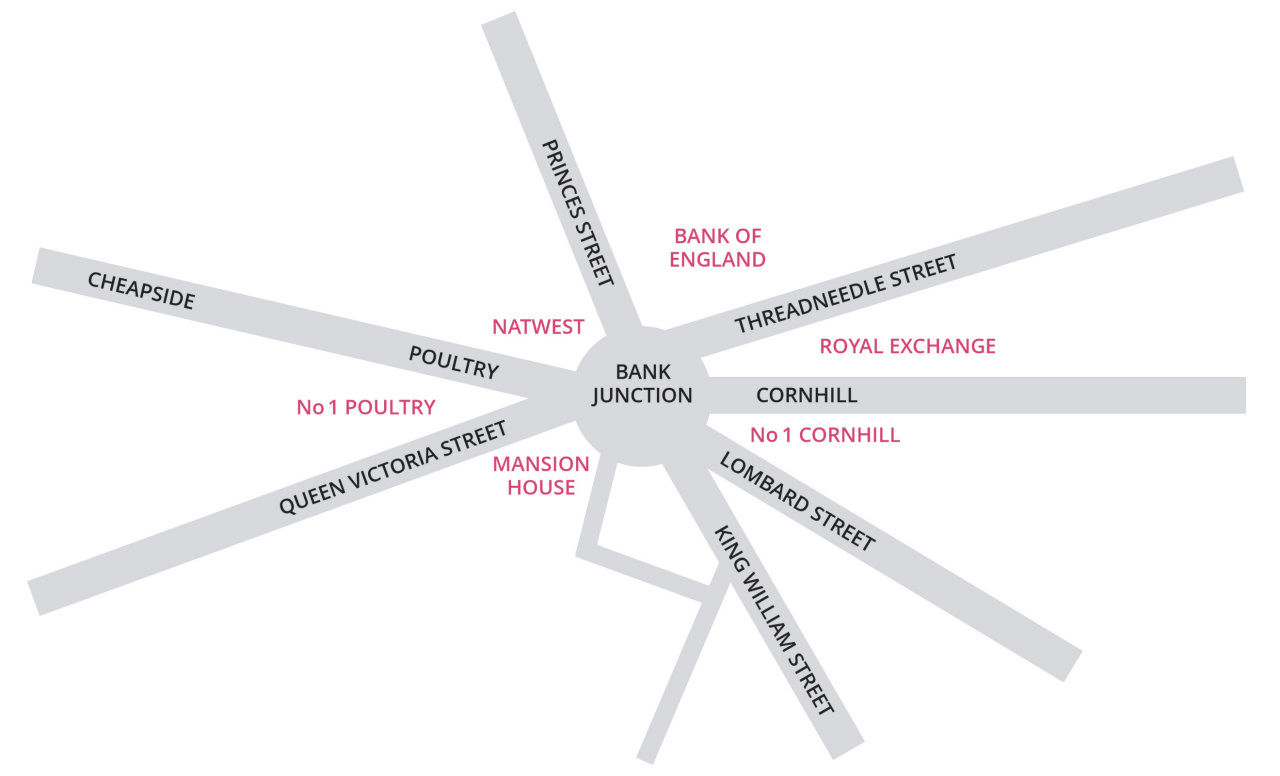

From the top of Mansion House Place, we’re going to cross over Bank Junction, where eight streets meet – but before we do, I’ll just explain what the buildings are that you can see from here, in case you aren’t familiar with the area.

Straight across in front of you is the imposing Bank of England on Threadneedle Street. To the immediate right of it, between Threadneedle Street and Cornhill, is the unmissable frontage of the Royal Exchange, which we are going to visit next. Finally, the road branching off on your immediate right is Lombard Street. I’ll say more about what’s on the left side in a moment.

So, cross over Lombard Street and then Cornhill to the little plaza in front of the Royal Exchange. The statue in the middle of Cornhill is a memorial to James Henry Greathead, the civil engineer. He took Marc Brunel’s invention of the movable tunnelling shield, which he had used to build the first tunnel under the Thames and adapted it to build London’s underground network. And the plinth on which the statue stands cleverly disguises a ventilation shaft for the underground line beneath it.

Standing on the little triangular island front of the Royal Exchange, time for another brief orientation. If you look back across Bank Junction, you get a good view of the Mansion House. To the right of it is the modern pink and cream distinctively shaped Number One Poultry that we saw earlier. To the right of that, on the triangular corner between Poultry and Prince’s Street, is NatWest’s City of London office.

Finally, alongside on your right, is of course the imposing and rather forbidding Bank of England building.

The Bank of England was established in 1694 and is the second oldest bank in the world. It’s been on this same site since 1734, though much of the original building was demolished during renovation and extensions in the 1920s. Britain’s gold reserves – and those of thirty other countries – are stored in vaults deep underneath. There are said to be around 400,000 bars.

You can’t visit the Bank itself, but you can visit its small museum which situated in the adjacent Bartholomew Lane. Admission is free and it’s open Monday to Fridays.

I have put more information about the Bank of England in the appendix.

But now, back to where we are standing – the most prominent feature is a large statue of the Duke of Wellington mounted on his horse. This commemorates the Duke’s assistance to the City of London in ensuring a bill was passed in the House of Commons to allow the rebuilding of London Bridge. Immediately behind it is a commemorative memorial to the City of London Royal Fusiliers. (I find it interesting to read the names of the many City of London’s military companies; for example, the 28th Battalion of the Artists Rifles, the 8th Battalion of the Post Office Rifles and the 25th Battalion of Cyclists.)

Provided the Royal Exchange is open then go into the main entrance and take a little look around. In the centre is a Fortnum & Mason bar and restaurant that is surrounded by a number of exclusive shops, whilst the floors above are used as offices.

Having done so, make your way to the rear of the building and leave by that exit.

Note – If the Exchange isn’t open, (i.e. at weekends) then walk around the building to the left and you can pick the walk up as below.

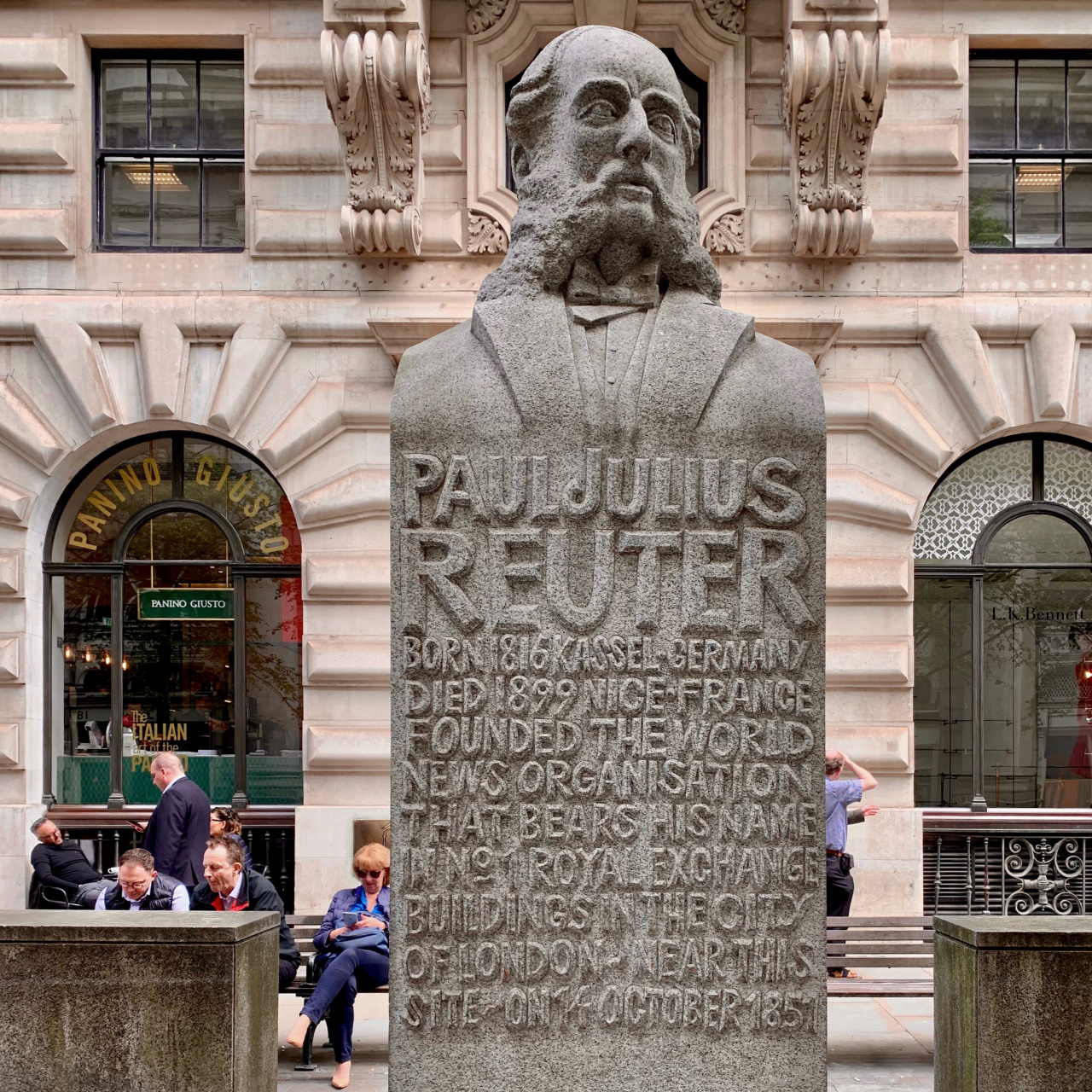

Leave the Exchange through the exit door at the rear of the building – but just before you walk through the ‘vestibule’ and into the street, notice the statue of Abraham Lincoln. Also, to the left of that there’s a door marked ‘No 1’ which was the office of Paul Julius Reuter – this was where he first set up his famous world news organisation. Over a hundred years later Reuters is still providing many of the world’s leading newspapers and other media outlets with news stories.

There’s a memorial statue to him in the street outside the exit doors, explaining that he was born in Germany in 1816 and died in Nice, on the French Riviera, in 1899. On the rear of the memorial are details of the Reuter organisation, explaining how it revolutionised news gathering across the world. It’s unusual in that it is in a ‘raised printer’s typeface’. I’ve put more about it the appendix.

We’re going to turn to the right along the pedestrianised Royal Exchange – but before we do, look to the left-hand end of the Avenue and you’ll see the memorial statue to George Peabody.

Peabody was an American multi-millionaire who founded what became the JP Morgan Bank, the largest financial organisation in the USA. He donated around half his wealth to charitable causes and is said to be the ‘father of modern philanthropy’. Whilst many of his philanthropic projects were in America, he also became a generous benefactor in London, setting up the Peabody Trust that financed many projects to help the poor of London. The trust built a number of social housing estates that offered ‘decent accommodation to artisans and the labouring poor of London’. Most of these are still lived in today, though now renovated and modernised. He was also very keen on education and built a number of libraries and schools. In today’s money it is estimated that he gave away almost £150 million.

(And a reminder … if the Exchange building is closed on the day you visit, then walk around it to the left (with the Bank of England on the other side of the road) – you will see the statue of George Peabody at the start of Royal Exchange – turn right and pick up here.)

At the top of Royal Exchange is a drinking fountain that was originally erected by the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association.

At the end of the road, turn to the right down Cornhill – and still on the water theme, notice the old pump with a sign on it dated 1755. On the other side there is more information explaining that a well was first dug here in 1282.

Turn to the right, then cross over Cornhill and walk down for just a few yards before turning left up Change Alley (it’s just to the right-hand side of the Pitcher and Piano pub, which was once the offices of the Scottish Widows Life Assurance).

This was once a very important part of the City, although it was badly damaged by bombs in the Second World War and so a lot of odd rebuilding has taken place since.

At the ‘cross lanes’ notice on your right a plaque explaining that this was the site of the Kings Arms Inn, where in 1756 the first meeting of the Marine Society took place.

After just twenty yards along Change Alley we turn right at the little ‘cross lanes’ and follow the passage around to where it emerges into Lombard Street.

Opposite you, on the other side of Lombard Street, you’ll see a Sainsbury’s Local and a plaque on its wall explains that from 1691 until 1785 this was the site of Lloyd’s Coffee House.

Lloyd’s Coffee House was the forerunner of the world-famous Lloyd’s of London, an extremely important meeting place for merchants, ship owners as well as sailors. News and information about shipping would be exchanged here and deals struck. Edward Lloyd had a pulpit installed from which maritime auction prices would be announced, and he also began publishing a newspaper containing shipping news and information about shipping insurance. In 1774, merchants who had begun to specialise in insurance, moved to the Royal Exchange that we visited just now.

Turn left up Lombard Street and just a few yards along notice the iron sign hanging above you. In case you aren’t sure, it’s a grasshopper and was the emblem of Thomas Gresham, one of the City of London’s most illustrious citizens, a trusted confidant of Elizabeth I, several times Lord Mayor, successful businessman and generous benefactor. This was both his home and in 1563, became the site of his newly formed Martin’s Bank. It only closed when the bank was sold to Barclays in the 1960s.

Continue on for seventy-five yards or so then turn left into Birchin Lane.

Halfway along, where the sandwich shop protrudes into the lane, turn right into the very narrow Bengal Court (though before you do notice the sign on the wall that commemorates a Royal Naval officer who was killed here in 1944 whilst trying to prevent a robbery on a jewellery shop.)

When you reach the little modern square, turn immediately to the left, passing the George & Vulture Pub and then after a few yards you reach the ‘cross lanes’. (The famous Simpson’s Tavern is a few yards down the lane on your left.)

In front of you is the Grade II listed Jamaica Wine House, which opened in 1652. Although it’s been refurbished and – despite its name – it is now more of a pub than a wine bar. The interior has been well-preserved, with several small rooms and plenty of dark wood panelling. Worth a quick look inside if you have time.

The Jamaica Wine House was the first of the famous London coffee houses. The wall plaque says it was ‘at the sign of the Pasqual Rosée’s Head’. It was known locally as the Turk’s Head, probably because Pasqual Rosée, who had set it up, was helped in doing so by a gentleman who traded in Turkish goods and imported their coffee. In the 17th and 18th century, coffee houses were public social places where men would meet for conversation, learn the news of the day and carry out commercial dealings. The diarist Samuel Pepys was one of its early regular customers.

At the little ‘junction of the lanes’ turn right, passing along the front of the Jamaica Wine Bar and the St Michael’s churchyard next to it. Directly ahead are a pair of double wooden doors with a sign to their right that says, ‘No. 7 St Michael’s Alley’. If the doors are open, then walk inside – it’s the rear entrance to a remarkable Wetherspoon’s pub called The Crosse Keys.

Time to stop for a meal?

Opened in 1757, Simpson’s Tavern is still a City favourite and while the prices may have changed (though a full roast beef lunch with all the trimmings is less than £16) the décor and furnishings haven’t. Plenty of wood panelling and wooden seats that are in effect stalls – complete with a brass rail above where gentlemen can place their top hats.

Time to stop for a meal?

Opened in 1757, Simpson’s Tavern is still a City favourite and while the prices may have changed (though a full roast beef lunch with all the trimmings is less than £16) the décor and furnishings haven’t. Plenty of wood panelling and wooden seats that are in effect stalls – complete with a brass rail above where gentlemen can place their top hats.

The original Crosse Keys pub opened in the 1550s and was a very busy coaching inn with around forty coaches arriving or departing each day! Its courtyard was also used by Shakespeare’s actors to perform his plays. The pub was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. In 1913, the site became the banking hall of the headquarters of the Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation (now of course, HSBC). More recently it was bought by Wetherspoons who, as usual, have done an amazing job with the restoration – I love the glass domed roof, the gallery as well as the original signs for the toilets that direct you downstairs to the ‘Ladies & Gentlemen’s Washrooms’.

Leave the pub through the same rear door through which you entered and turn to the right, (the churchyard railings will be on your left) – the short 15-yard passage will lead you around to the right into Corbett Court. Go down the steps then turn left up another small lane, alongside the Bengal Court Restaurant.

After about ten yards you will see the entrance to another well-known pub – The Counting House, now a Fullers ‘Ale and Pie House’. Once again, it’s worth taking a little look in to see how successfully this former banking hall has been preserved and turned into an enormous pub. With its high ceilings, enormous glass domed roof, ornate dark wood, and marble and brass fittings, it really is quite special.

Leave the pub by the way you went in and walk straight ahead of you.

Note though … If you didn’t go inside the pub, then simply turn to the right out of Corbett Court, and walk down St Peter’s Alley – but make sure you now have St Peter’s churchyard on your left.

Notice the raised graves in the churchyard; this was once the burial ground for the parishioners of St Peter’s Church and Charles Dickens refers to it in ‘Our Mutual Friend’, saying how the graves were “conveniently and healthily elevated above the living”. The church was said to have been founded by King Lucius in AD 179, destroyed in the Great Fire and then like so many others in the City, rebuilt by Wren. It’s now used as a study centre to train men and women for the ministry

And when you reach the bottom of St Peter’s Alley, notice on your left the shop called Ede & Ravenscroft, ‘robemakers and tailors’, who have been in business here since 1689.

You are now in Gracechurch Street – and directly opposite is the entrance into the delightful Leadenhall Market, where we head next. The market has been wonderfully preserved with the beautifully restored shop fronts and glass roofed rotunda and I find it fascinating. Whilst I have put some information here, I have written a little more for the appendix.

It’s bustling during weekday lunchtimes and in the early evenings when hundreds of office workers flock here for a bite to eat or an after-work drink. Particularly popular is the cheese shop and bar, whilst next door to it is Viandas – one of my personal favourites. They sell excellent Spanish hams and wines. Until recently a couple of doors down, was a pen shop, with fountain pens costing hundreds or even thousands of pounds, but sadly, and I suppose not surprisingly, it has recently closed. Opposite, there’s a shop selling fine wines, whilst on the corner is a ….err, a Pizza Express! But at least its shop front is in keeping with its historic surroundings.

When you reach the central rotunda, continue walking ahead, passing the Lamb Tavern (which was founded in 1780) on the left and on your right the Reiss fashion shop.

This takes you into Leadenhall Place.

In the film ‘Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone’, Harry enters Diagon Alley via the wizarding inn called the Leaky Cauldron. Location shooting was done in Bull’s Head Passage, which is just around the corner from Leadenhall Market, opposite the Loch Fyne restaurant. And I have to say, it’s definitely not worth looking for – the Leaky Cauldron is now just a modern looking opticians’ shop that isn’t even in keeping with the rest of the market shops.

Immediately you’ve walked past the Lamb Tavern and Reiss, you can’t miss on your left the huge and still somewhat ‘futuristic’ building (although it’s been here now for nearly forty years) of Lloyd’s of London. I’ve written more about the building in the box below and more on the history of Lloyd’s in the appendix.

Continue past the Lloyd’s Building and at the bottom, turn left into Lime Street. But as you do, look to the right and in the background, you can see the enormous 39-floor 600 feet high skyscraper that’s been nicknamed the ‘Walkie Talkie’. Looking at its shape, you can see why it got that name, though its official (and boring name) is 20 Leadenhall Street. And I’ll just mention here that on its roof is the Sky Garden – definitely worth a visit sometime – check their website for details of how and when you can visit.

Further down Lime Street, you can’t miss the new 28-storey office block Willis Building (named after its major tenant), which was designed by Sir Norman Foster. To the left is the front aspect of Lloyd’s – if you look down to the lower level, you’ll see the Lloyd’s gift shop – some nice items for sale but generally rather expensive.

The very new building on the right at the bottom of Lime Street is known as ‘The Scalpel’, though its official (and once again boring) name is 52 Lime Street. The reason for its unusual design was simply that the planners wanted to reduce its impact on the view of St Paul’s Cathedral from Fleet Street.

Leadenhall Street runs from left to right and just pause for a minute or two here to take it all in – so much development has happened over the past couple of years – and is still happening. It’s quite a breath-taking scene, to me more reminiscent of Manhattan than London.

If you look to the left, on the other side of Leadenhall Street, you can’t miss the dramatic looking skyscraper ‘on legs’ with an open plaza in front. Again, nobody seems to bother with its official name of the ‘Leadenhall Building’ or ‘122 Leadenhall Street’, as because of its shape it has been nicknamed ‘The Cheesegrater’. As with the Scalpel, the design of the building has been dictated by the need to preserve views of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Architecturally, I think it is quite interesting, with external escalators leading up to the reception level on the raised ground floor. In that respect it has some similarities with the Lloyd’s building opposite – i.e. ‘exposed’ service facilities and lifts. And talking of lifts, The Leadenhall Building is said to have the fastest lifts in Europe.

Directly in front of you is the large plaza of the older 23-storey and 380 feet high Commercial Union building (now called Aviva). It was built in 1969 and is about to be demolished to make way for the new 56-storey Number 1 Undercroft. The new building has already been given two nicknames; one being the Diamond and the other The Trellis (both on account of its unusual structural design).

Slightly to the right of it you can’t miss the unmistakable shape of the ‘Gherkin’, now one of the City’s most iconic buildings.

There’s a real contrast on the other side of the road as just to the right is the very much smaller and older – and now looking rather incongruous – Lloyds Bank. I wonder how much longer it will be before it is demolished and yet another skyscraper erected on the site.

With so many new skyscrapers being built in the City, I have written a few words about the changing skyline of the City of London in the appendix.

Cross over Leadenhall Street and walk down St Mary Axe to the right of the Commercial Union building. A few yards down on the right is the old church of St Andrew Undershaft. Built in the 12th century, it’s one of the few churches in the City of London to have survived both the Great Fire and the Blitz. Sadly though, after all that, its beautiful 17th century stained glass windows were destroyed by IRA’s bombs in the 1990s – more of which later.

Next to it is Fitzwilliam House, which is built on the site of another church – the ancient Church of St Mary Axe, which gave its name to both the street and one of the City of London’s earliest medieval parishes. It was built around 1230 and demolished in 1561, after which the parish united with St Andrew Undershaft. (And Fitzwilliam? He was one of the City’s early mayors.)

And why the unusual names for both churches?

Firstly, St Mary Axe Church (its full name was the Church of ‘St Mary Axe, St Ursula and her 11,000 Virgins). According to the historian John Stow in his 1603 ‘Survey of London’, an axe was once hung over the east end of the church. A document dating back to the time of Henry VIII says it was a holy relic, more specifically, “An axe, one of the two that the eleven thousand Virgins were beheaded with”. This is a reference to the legend that Saint Ursula, returning to Britain from a pilgrimage to Rome, and accompanied by eleven thousand handmaidens, refused to marry the chief of a Hunnish nomadic tribe they met on the journey and was executed, along with all of her handmaidens.

And ‘St Andrew Undershaft’? A huge maypole used to be erected alongside the church each year and was said to have been taller than the church’s tower. Maypoles used to be called ‘shafts’, so the church was built ‘under the shaft’. However, in 1547, the maypole was so badly damaged by rioters who felt it was ‘pagan and heathen’ that it was subsequently broken up.

As you pass Fitzwilliam House, look to the left across to the other side of the road and the old stone building you can see behind the Commercial Union Building is St Helen’s Church, which I mention shortly.

Next on the right is the easily recognisable Gherkin building, which opened in 2003. It was nicknamed the Gherkin because of its shape, though I’m not sure it resembles any gherkin I have ever seen. It’s been compared to everything from an aircraft engine to a torpedo – but the name Gherkin has stuck. However, its correct but mundane name is ‘30 St Mary Axe’.

If you want to visit St Helen’s Church, then cross over and walk down the road opposite the Gherkin – it’s on the right of the ramp to the underground carpark. Its interior is different from that of most churches and worth looking in if you have time (and if it’s open – it often isn’t).

Continue on along St Mary Axe, and next to the Balls Brothers wine bar, at No. 38, are the offices of the Baltic Exchange who moved here after their building was demolished by the IRA bombing, when the Gherkin was built on the site it previously occupied.

The Baltic Exchange was established in 1774 by members of the maritime industry to provide market information and is today “the world’s only source of maritime market information for the trading and settlement of physical and derivative shipping’. It has six hundred members across the globe who encompass the majority of the world’s shipping. Members are also responsible for a large proportion of all ‘dry cargo and tanker fixtures’, as well as the sale and purchase of merchant vessels.

![]()

Almost opposite, turn left into the pedestrian alley that leads through the enormous new office building that stretches from here through to Bishopsgate, where we head next.

When you reach the central courtyard, where the passages split, take the one to the right, then turn left into Camomile Street.

The building opened in 2020 and was given the imaginative name of ‘100 Bishopsgate’. (I understand that it is the City of London planners who insist that these new skyscrapers are simply given the street number, rather than a more interesting name. It is almost 600 feet high with 40 storeys. Adjoining it is a smaller building that has an entrance in St Helen’s Place, and which we see shortly.

We are going to turn left down Bishopsgate, but before we do I’ll just mention the skyscraper office building on the opposite corner. Until recently it was known as the ‘Heron Tower’, though when it opened the City of London Corporation didn’t like the name and insisted it was changed to ‘110 Bishopsgate’. However, everyone continued to call it the Heron, and despite it recently being renamed ‘Salesforce Tower’ – after a huge American technology company that is now one of the major tenants – it is still widely known as the Heron. When it opened in 2011, it was the third tallest building in London, though it’s certainly not now.

Bishopsgate is the start of the A10, one of the principal roads leading out from London through Essex to Cambridge before ending in Kings Lynn in Norfolk. (And although not really relevant, I find the background to how the English road numbering system was devised, based on the four major roads that spread out from London, quite interesting and in case anybody else is interested, I have included it in the appendix).

Turn to the left down Bishopsgate and immediately after the new 100 Bishopsgate building on the corner you’ll see a small gate on your left that leads to the rear garden of St Ethelburga’s Church – if it’s open, perhaps take a look inside. It’s another church that has a much longer name – officially it’s the Church of St Ethelburga-the-Virgin within Bishopsgate – (St Ethelburga was a 7th century abbess from Barking in Essex).

Continue on down Bishopsgate for just a hundred yards or so until you come to a pair of splendid gates with columns either side. This leads into St Helen’s Place and although the sign says it’s a private road – hence the gates – it is open to the public. The road and the buildings on either side are owned by the Guild of Leathersellers, one of the city’s ancient Livery Companies which received its royal charter in 1444. The site covers some six acres of what must be some of the most valuable land in Britain. The considerable rental income goes towards the charitable work that the Guild still does to this day.

Towards the rear and on the left of St Helen’s Place is the entrance to the restaurants in the seven-storey extension of 110 Bishopsgate, which I mentioned previously.

Cross over at the pedestrian lights and continue walking on down Bishopsgate – you can’t fail to notice another huge new skyscraper a couple of hundred yards further down on the left.

It’s 22 Bishopsgate (yet another skyscraper imaginatively given the name of its street address), which opened in spring 2022 after a delay of many years. At 912 feet high and with 63 floors, it is the second tallest building in Britain (after the Shard) and with almost 1.5 million square feet accommodating up to 12,000 workers it has the largest office accommodation of any building in Europe.

It’s been called a ‘vertical village’ by the developers, though I feel it stretches the imagination somewhat to compare a skyscraper with a ‘village’! In fairness though, it does offer a 20,000 square foot fresh food market. and ‘food hub’, a Wellbeing Retreat floor with medical facilities, gym and separate studios for Pilates and yoga, as well as a health spa and juice bar. There’s also a 25-foot glass climbing wall (with scary views across London!) a curated ‘art walk’, 300-seat auditorium, a bike hub with 1,700 spaces (the biggest in London), cycle repair shop with showers and changing facilities for those riding to work. In addition to all of this, there’s a free-to-enter public viewing gallery on the 58th floor, with a three-storey restaurant and bar on the three floors above. And quickly getting to the top floors appears simple as there are 57 lifts (the fastest in Europe), 26 of which are ‘double-deckers’, and ten escalators.

As you walk past, you might notice the strange canopies, which look as though they are there to protect passers-by from the rain. However, they are too high up for that, and instead are there to deflect the wind tunnel effects that are caused by tall buildings.

As you approach the junction where Threadneedle Street forks to the right, notice on your right the magnificent Gibson Hall.

We turn to the right up Threadneedle Street and after 50 yards or so turn right through a pair of iron gates into Adam’s Court.

The passage takes you past a small ‘courtyard garden’ – take a look inside as from here you get an excellent view of the 600-feet high Tower 42, previously known as the NatWest Tower, where part of the NatWest bank relocated after leaving Gibson Hall.

From the garden, turn to the left down the steps, pass through the next gate and continue past the Ball’s Brothers wine bar – this brings you out into Old Broad Street, where there’s an old police box on the right.

Almost directly opposite on the other side of the road you will see an archway with the words ‘Austin Friars’ carved above it, where we walk next. Go through the arch, follow the lane around and, as the lane bends to the right, notice under the sign ‘No.4 Austin Friars’, a statue of a bearded monk holding a book that’s set into the wall. Opposite is the ‘tradesman’s entrance’ to the Drapers’ Hall, the front of which we see later in the walk.

Austin Friars takes its name from the Augustinian priory that once stood nearby. It was built in 1253 but attacked in the Peasants Revolt in 1381. I like the story that the so called ‘Prince of the Humanists’ Erasmus of Rotterdam, a Dutch priest, philosopher and theologian stayed in the priory in 1513, but refused to pay his bill, complaining about the quality of the wine he was offered!

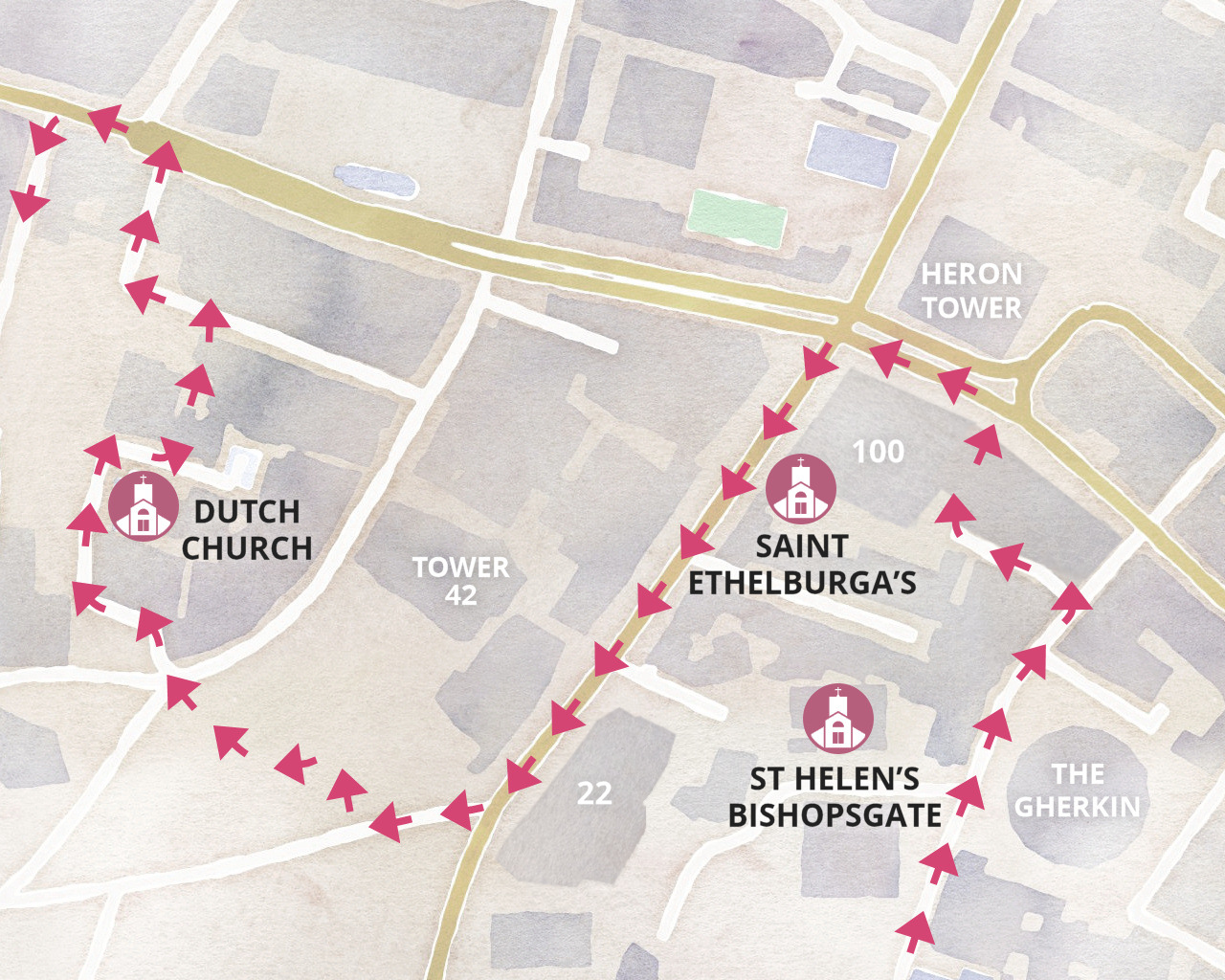

At the end of Austin Friars is a Dutch Church that was built in 1550, completely destroyed by bombs in the Second World War and subsequently rebuilt. The main entrance is around to the right.

The Dutch Church was the first non-conformist church in England and it has been here since 1550. It’s the oldest Dutch-language Protestant church in the world and known in the Netherlands as the “mother church of all the Dutch reformed churches”. It offered services to Protestant refugees from the Low Countries (Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg) as well as to others coming from northern Europe. The original building was destroyed by bombs in the Second World War and the church you see today opened in 1954. Inside, you can’t fail to notice its simplicity – very different from a traditional Church of England or Catholic place of worship – though there is a splendid stained-glass window.

Opposite the front of the church at No.12, the red-brick building is the Furniture Makers’ Hall, one of the more recent guilds. Unlike many which go back to medieval times, this wasn’t established until 1952 and only received its royal charter in 2013.

The Furniture Makers’ Company was set up by the furnishing trade and aims to promote the industry, encouraging young people within it to undertake additional training and study for relevant qualifications. They also give ‘marks of distinction’ for the best in design and manufacturing each year, as well as providing financial and other assistance to people working within the furniture industry who fall on difficult times. It’s supported by all sections of the furniture industry – the major manufacturers, retailers, designers, craftsmen and students. I was surprised to discover it’s even actively supported by companies such IKEA, John Lewis and Marks & Spencer.

Next to the Furniture Makers’ Hall (to the right of it) turn left into Austin Friars Passage – this takes you into Great Winchester Street – and at the top, turn again into the busy street known as London Wall.

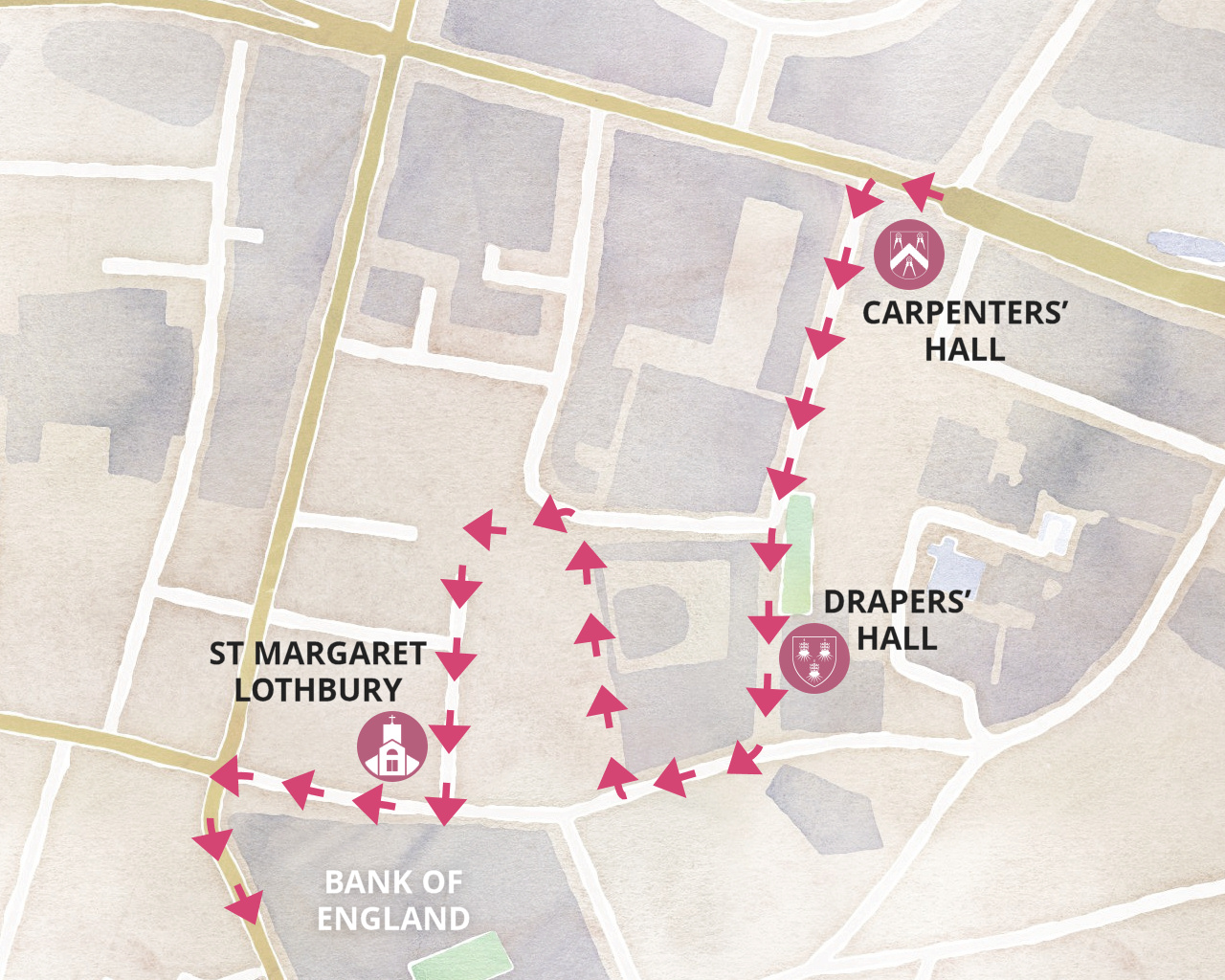

Take the next left into Throgmorton Avenue, passing under the bridge formed by part of the first-floor banqueting hall and through the large gates – these are part of the lovely building on your left that is the Hall of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters. As you walk down the street, notice the little shields on some of the buildings, doors and gates in the street – they are the Carpenters’ coats of arms and signify that these buildings are owned by them. Indeed, this is their street – hence the gates you have just walked through.

When I was researching this I discovered that there were two livery companies for people who worked with wood. This one – the Carpenters’ Company – was for the craftsmen who used nails and pegs in their work, while the Worshipful Company of Joiners and Ceilers used adhesives. The Carpenters’ Hall was built here in 1492 and since then there have been three on the site. The previous hall was completely destroyed in an air raid in 1941 and this one opened in 1960.

![]()

As you continue down Throgmorton Avenue, you pass Austin Friars on your left, where you were just now, and at this point the ownership of the road changes from the Worshipful Company of Carpenters to the Worshipful Company of Drapers, (a tell-tale sign are the lamp posts with the Drapers’ emblem on them). You see their large hall and its garden on your left.

And the name ‘Throgmorton’? That came from Nicholas Throckmorton, who joined the household of Catherine Parr and became Elizabeth I’s ambassador to both France and Scotland.

At the end of the road pass through the large gates (reminding us again the road is privately-owned) and turn right into Throgmorton Street. But as you do, look along to your left and notice some of the older and interesting houses on the left-hand side that amazingly survived the bombing raids of the Second World War – something that few buildings in the area did. It’s the upper floors and roof gables that I find particularly interesting.

Notice also the faded and worn sign over the door of the first building that says it was once a Lyons Restaurant.

Finish: Here, optionally |

Continue walking (to the right) along Throgmorton Street and ahead of you is the rear of the Bank of England.

This can easily be the end of the walk – in which case simply turn left when you reach Bartholomew Lane, which takes you past the Bank of England’s museum. At the top turn right and you are back to Bank Junction, where you can catch a bus or the tube.

However, if you feel up to just a five- or so-minute extension to explore a couple more lanes, then turn right up the side of the Coya Peruvian restaurant into Angel Court.

At the top of Angel Court turn left into Copthall Avenue and follow it around for about 100 yards, (you’ll see a telephone box on your right) and turn left into Copthall Buildings.

Continue for just a few yards to where the road bends slightly to the left and where Telegraph Street begins turn sharp left down an unnamed passage. (If you have got as far as the Telegraph pub then you’ve gone too far!)

The passage will lead you into Tokenhouse Yard – it was built in the reign of Charles I and initially the London home of the Earl of Arundel. As you enter the yard, take a look at No. 12 to the right. Called Token House, it was built in 1871 and was originally the head office of merchant bankers, later becoming the offices of Cazenove. They were (and still are) ‘upmarket’ investment bankers who at the time, were known for their liveried footmen who would meet and greet customers who visited the bank. Notice the lion’s heads on either side of the entrance door. The house, whilst no longer their offices, is now Grade II listed.

And the name ‘Tokenhouse Yard’? It’s because in the 17th century tokens were issued here – they were small coins that were given by traders to customers prior to low denomination copper coins, such as farthings, being available.

At the bottom of Tokenhouse Yard turn right back into Lothbury, then passing the rear of the Bank of England on your left. On your right is the Parish Church of St Margaret Lothbury. A board just inside explains that the first rector was ‘Reginald the Priest’ – in 1181.

Notice 41 & 42 Lothbury, also on the right – this impressive building was once the headquarters of the Westminster Bank. It’s now offices and if you’re here on a weekday, it’s worth popping in to take a look at what was the magnificent banking hall on the ground floor that has been wonderfully restored. You can’t go in very far, but you can certainly see what was the banking hall.

Finish: Princes Street |

Continue almost to the end of Lothbury – notice the statue of Sir John Soane, the architect of the original Bank of England building – and turn left into Princes Street. If you continue to the bottom you reach Bank Junction where there are plenty of buses and tube lines.

HOPE YOU’VE ENJOYED THE WALK!

If you have any comments or spot any errors, or have suggestions for improvements or other feedback, please contact me.