Updated: 5 September 2021 |

|

Length: About 2 miles |

|

Duration: Around 3 hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

A walk through St James’s

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WALK

The walk takes us along Jermyn Street, passing London’s oldest and most prestigious retailers of ‘gentlemen’s apparel’; along the smaller streets of St James’s that contain some of London’s best known and longest established five-star hotels and magnificent ‘city mansions’ such as Spencer House, the London home of Princess Diana’s family; the Royal Green Park; St James’s Palace, still the official residence of the reigning monarch; Pall Mall, famed for its historic clubs; the grand houses of Carlton House Terrace; The Mall and Waterloo Place, noted for its memorials and statues to illustrious figures from British history.

Start: Piccadilly Circus station |

|

Finish: Waterloo Place |

GETTING HERE

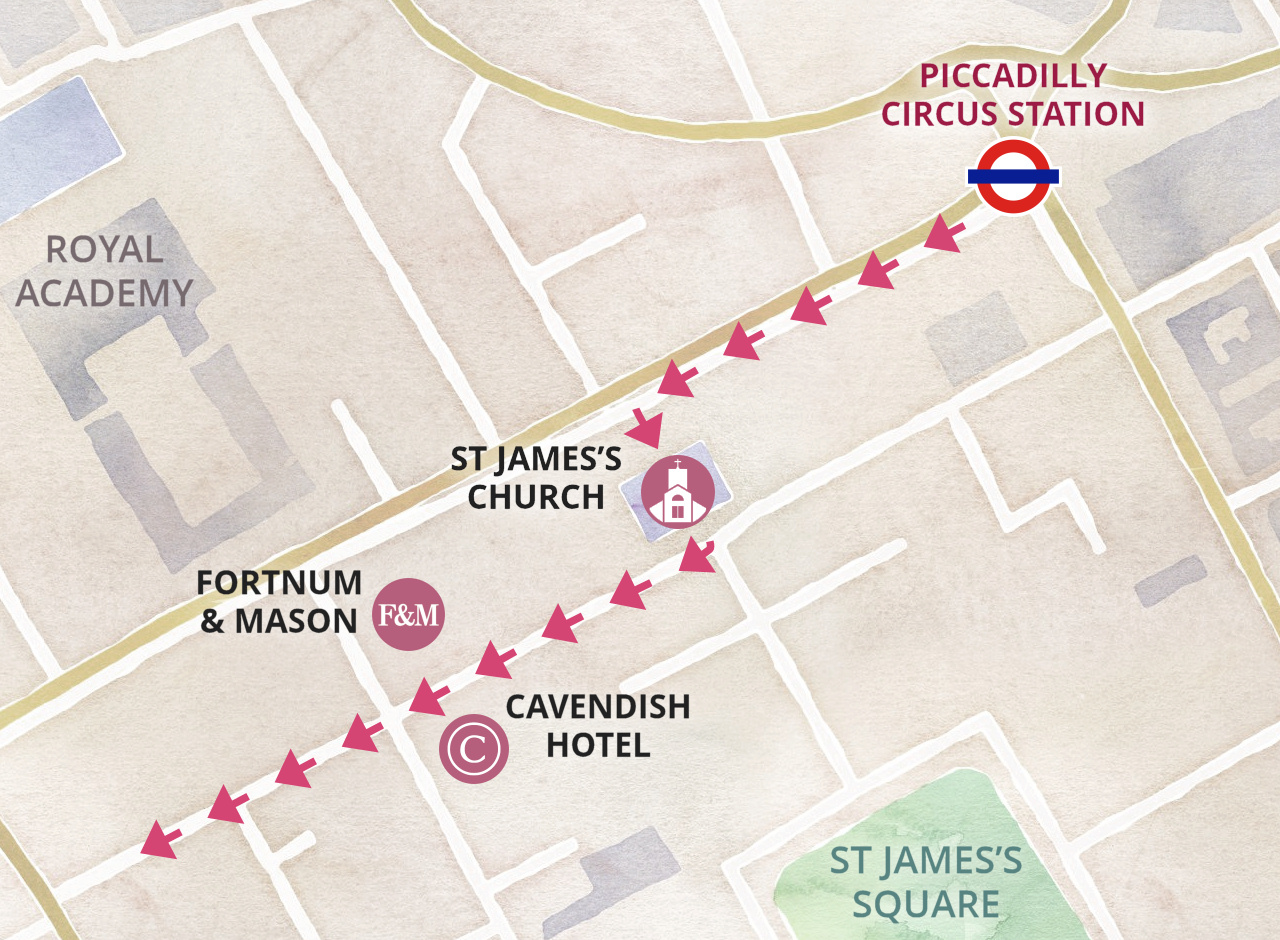

The walk starts at Piccadilly Circus. If you arrive by tube, then leave via Exit 3A – it’s marked ‘Piccadilly South Side’. At the top of the steps you are in Piccadilly – walk straight ahead until you reach St James’s Church.

If you don’t arrive by tube, then simply find your way to Piccadilly Circus and start walking down Piccadilly, following the directions above.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ST JAMES’S

The area known as St James’s is bounded to the north by Piccadilly, by Green Park to the west, to the south by The Mall and St James’s Park and the east by the Haymarket. It’s been an upmarket and aristocratic area of London for several centuries although it got its name from a leper colony, on the site of which now stands St James’s Palace!

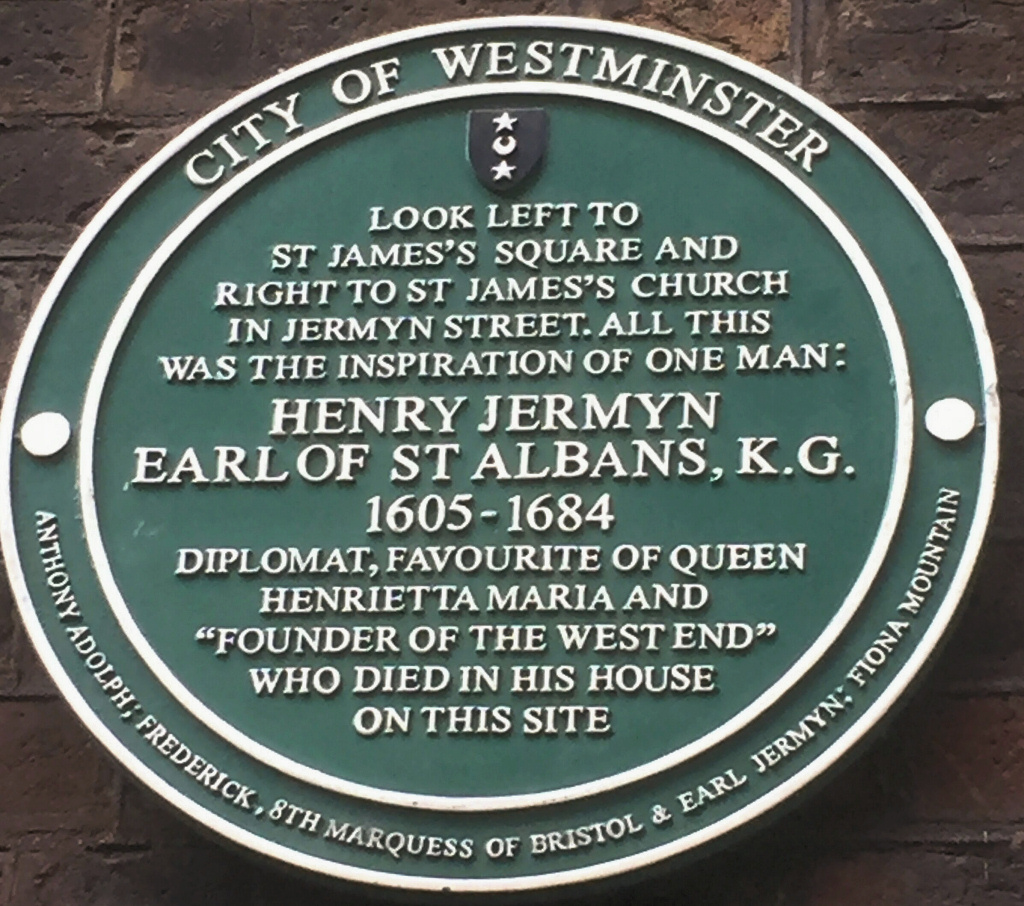

It was developed into the upmarket residential area that we see today by Henry Jermyn, who was the Earl of St Albans and former British Ambassador to Paris and The Hague.

He had been a strong supporter of Charles II and had worked hard, spending large amounts of his own money to help the king return to England to take the Crown, following the demise of Oliver Cromwell and his Parliamentary party. They, of course, had just a few years before executed his father, Charles I.

As a result, Charles offered to help when, several years later in 1661, Jermyn appealed to him for permission to build houses in the area then known as ‘St James’s Fields’, explaining that “the area is defective in point of houses fit for ye dwellings of noble men and other persons of quality …”. Charles knew he couldn’t afford to repay Jermyn for his previous assistance and, keen to avoid the fate of his father, he was taking care to be popular and friendly, not only with the population at large, but particularly with friends and supporters, such as Jermyn. So, he granted him the land.

Henry Jermyn began by building fourteen ‘grand mansions’ around a central square with a garden in its centre, which he named St James’s Square and we see this on the walk. He laid out a grid of four broad paved streets that led off from the square – King Street, Duke Street, Charles Street and York Street – (he was clearly trying to ingratiate himself with royalty when he named these streets) though he later named one after himself, Jermyn Street, which we will be exploring shortly and which over the years has been home to many distinguished persons – Sir Walter Scott, William Pitt, Duke of Marlborough, Thomas Gray and William Thackeray being just a few. It also gained renown for its exclusive (and thereby expensive) shops selling ‘gentlemen’s apparel’. With the number of ‘gentlemen’ living in St James’s, it soon became renowned for its many private clubs and we pass several of them on the walk.

Aside from Jermyn Street and St James’s Street, the area remained predominantly residential for many years, but has now become more commercial, particularly around St James’s Square where some of the world’s most prestigious companies now have their head – or sometimes just executive – offices. Not surprisingly, the rents here are amongst the highest in the world, in many cases even higher than in New York.

STARTING THE WALK

As you begin walking along Piccadilly, note the two rather magnificent buildings on your right, in particular Le Méridien Piccadilly. It was built in 1908 and formerly known as The Piccadilly Hotel. It has had several different owners, finally being bought in 1986 by Le Méridien – now part of Marriott International.

And in case you’re wondering – the name Piccadilly came from a tailor who lived in the street and who specialised in making ‘pickadils’ – special collars and hem trimmings – for which he became famous and very wealthy.

And to answer another often-asked question, no, there was never a circus as such here – the word ’circus’ was simply used to mean a ‘junction of roads.’

When you reach St James’s Church, turn into its churchyard, which was originally a burial ground. As with most London church graveyards it became overcrowded and burials were stopped in 1853. Until then, the main entrance into the church had been in Jermyn Street. Whilst you are in the church yard, notice the stone pulpit that’s on the wall outside of the church which enabled the vicar to preach to people outside as well as well as inside. These days the churchyard is regularly used for outdoor markets and, because of its food stalls, is a very popular place for local office workers to take their lunch.

Walk through the church – it is open daily – and leave through the door on the other side that takes you into Jermyn Street. (In the unlikely event it is closed then simply walk down the adjacent Church Place and turn right along Jermyn Street to pick up the walk.)

Once in Jermyn Street, cross over to the other side and walk to the right – this is where the ‘posh shops catering for gentlemen’ for which the street is so famous begin, many of which I have highlighted.

Paxton & Whitfield are one of the oldest cheesemongers in England. Established in Aldwych in 1742, they opened a shop in Jermyn Street in 1797 and moved to their present location at Number 93 just under a century later. They were granted a Royal Warrant for supplying cheese to Queen Victoria and today hold warrants for supplying cheese to both the present Queen and Prince Charles. Whether you actually want to buy any or not, it is worth your while taking a look inside at the wonderful selection. But don’t bother if you don’t like the smell of cheese – some of them seem quite potent.

Next door is the Northampton shoemaker Crockett & Jones, another long-established shop who have been making shoes since 1879. It’s a beautiful old, classic styled building – just look up at the balconies and windows above.

Floris the Perfumers at Number 89 are England’s oldest retailer of fragrance and toiletries. Founded by Juan Famenias Floris in 1730, they’ve been here ever since and are run by the same family – now the 9th generation. Take a look inside and notice the beautiful display cabinets that date back to 1851 when they were brought across from the Great Exhibition that was held in Hyde Park that year. Floris were granted a Royal Warrant in 1820 as ‘Smooth Pointed Comb-makers’ to George IV and have had a further nineteen other warrants since then. Today they hold the Royal Warrants for being official perfumers to the Queen Elizabeth II and manufacturers of toiletries to HRH Prince Charles.

Across the road is Princes House, an attractive Art Nouveau building that was once Princes Hotel. Within it are Grenson, who began making men’s boots in 1874, whilst next door is the entrance to the Princes Arcade, that contains shops of even more specialist nature, including one that seems to just sell gentlemen’s waistcoats – and I can’t help wondering how shops such as these survive in this day and age. Next to that is Barkers and the long-established Loake, who have been making shoes since 1880 and hold the Royal Warrant for making the Queen’s shoes. Then there’s the entrance to the exclusive nightclub and restaurant Tramps, and finally the world-famous Fortnum & Mason. They opened here in 1707 and I rather like their history, which begins with William Fortnum, a footman in the court of Queen Anne who had a sideline selling her partly burned candles. He eventually set up the shop here with his landlord, Hugh Mason and they enjoyed considerable success. For many years the shop has held the Royal Warrant for supplying groceries to the Palace – though I can’t help wondering whether that includes candles …

Back on the other side of the road at number 87 is Hackett’s, once the home of Isaac Newton, one of the world’s greatest scientists and mathematicians. He lived here for some eighty years, between 1642 and 1722.

Next are two more shoemakers … the first is John Lobb, who’ve had a particularly interesting history and I write more about him when we see their other shop later in the walk, where they still make handmade shoes, whilst next door are Foster & Son, who have been here since 1847.

Then comes the ugly looking Cavendish Hotel, designed in a sad attempt at a sort of Brutalist style of architecture, complete with a rather oddly angled tower block. Even the interior, to me at least, appears featureless and bland. Certainly not a five-star hotel I would ever choose (if I could ever afford to stay in one).

There’s been a hotel on the site since the early 1800s and one of its earlier proprietors was Rosa Lewis (1867–1952). There’s a plaque on the wall giving more details of this celebrated ‘chef de cuisine and hotelier’. She often cooked for the likes of Edward VIII, the Duke of Windsor, Lord Northcliffe and General Kitchener. One of her sayings, which I rather like, was apparently, “It doesn’t matter what you do in the bedroom as long as you don’t do it in the street and frighten the horses.” Clearly quite a character, whose story was dramatised in the TV series ‘Duchess of Duke Street’.

![]()

Cross over Duke Street, where an office block called The Marq has recently been completed (April 2019), and on the other side is Alfred Dunhill. Dunhill’s go back to 1893 when, at the age of 21, Alfred Dunhill inherited his father’s saddlery business, which was situated on London’s busy Euston Road. He had spotted the growing interest in motor cars and developed a range of products for the growing number of owners of those early cars – everything from leather coats and goggles to picnic sets, car horns and lamps – thus giving the company the name ‘Everything but the Motor’. After inventing the ‘windshield pipe’, thus enabling a gentleman to smoke his pipe whilst driving an open top car, he became a tobacconist! This isn’t their main shop though, as that is a short walk away in Mayfair.

Next is the exclusive Italian tailors Boggi (and I can’t help but think that isn’t the best name for such a posh London shop), then after New & Lingwood, who were established in 1865, is the Piccadilly Arcade that contains yet more exclusive and rather unusual shops. (I noticed one that primarily seems to just sells cufflinks, another bespoke watchstraps – while another simply sells high class mustard.) The Piccadilly Arcade runs through to Piccadilly, continuing on the other side where it is called Burlington Arcade.

Outside of the arcade, you can’t miss the statue of George Beau Brummel (1778 – 1840). The inscription says that he ‘embodied the spirit of St James’s past and present’ and includes his comment, “To be truly elegant one should not be noticed”. Brummel was a well-known figure in the West End at the end of the 18th and early 19th century, patronising both the area’s most exclusive tailors as well as the gentlemen’s clubs.

Back on the left-hand side is Taylor of Bond Street, who began business in 1854 and describe themselves as ‘Gentlemen’s Court Hairdressers’. They’ve certainly adapted with the times, now selling through John Lewis stores as well as having a thriving mail order business. Next to them is Hilditch & Key who have been making and selling their shirts here since 1899. They clearly embodied the idea of ‘going out to get business’, by sending their experienced staff, armed with tape measures, to visit ‘young gentlemen’ at universities!

Cross Bury Street and you’ll see Turnbull & Asser, who were established in 1885. According to their signage they are ‘hosiers and glovers’ but now offer a range of other gentlemen’s apparel and hold the royal warrant as shirt makers to HRH Prince Charles. (And interestingly, during the First World War they invented a raincoat that doubled up as a sleeping bag for the military.)

However, many of these seemingly long-established businesses are all relative newcomers compared to Wiltons, on the opposite side of the road. It is one of London’s oldest and best-known restaurants and has been “satisfying the bellies of the rich and famous since 1742” – over 275 years. There’s a sample menu in the window so you can at least check you have enough credit on your card before you order. The sign outside says they are noted for “the finest shellfish, seafood and game and purveyors of oysters for Royal Households from 1838 until 1938”. (But why only until then I wonder? Did a member of a royal household then have an upset stomach as a result of a bad oyster?)

Back on the left side are two more shoemakers, Crockett & Jones, here since 1879 and Tricker’s, founded by Joseph Tricker to make heavy country boots and shoes for ‘farm and estate owners and the landed gentry’ some fifty years earlier in 1829. They hold the Royal Warrant for being HRH Prince Charles’s shoemakers.

Emma Willis sell gentlemen’s handmade shirts that they make in their own factory in Gloucestershire and Bates Gentlemen’s Hatter are still in the same shop as they were when they opened in 1898.

On both sides at the end of the street are two more long-established shops – on the left is Davidoff, originally makers of ‘fine cigars’ but their windows now display many other ‘gentlemen’s necessities’, including a fine selection of umbrellas. (Don’t think of popping in to buy one if its starts raining unless you have plenty of money to spend – I couldn’t see any under £100 – and many were a lot more expensive than that.) However, I do rather like the sign inside the shop that reads “Thank you for smoking”.

Finally, on the right-hand side is the beautiful old building that’s home to the Beretta Gallery, who’ve been trading since 1526 (and that’s not a typing error) and cater for ladies’ and gentlemen’s ‘town and country’ requirements. They’ve got shops (or galleries as they prefer to call them) in several of the major cities of Europe and are famous for their guns – the entire second floor is given over to them.

From here we cross over the equally historic St James’s Street … and walk up Bennet Street, which is almost directly in front of you on the other side of the street.

But before you start walking up Bennet Street, just take a quick look back at the Beretta shop on the other side – from here you can better appreciate how lovely the building is.

When you reach the top of Bennet Street, turn left into Arlington Street. The large white building you pass on your right is Arlington House – very expensive residential apartments – whilst on the ground floor on the left is Le Caprice, one of London’s most eminent celebrity restaurants.

Arlington Street looks as though it’s a dead end, which for cars it is, but if you walk to the end and look carefully, you’ll see a small flight of steps (often partly obscured by parked motorbikes) that passes underneath the house facing you – this takes you down into Park Place.

Emerge from the passage and turn to the right, and on your left you will see the small but elegant and exclusive St James’s Hotel and St James’s Club – the latter having been established as long ago as 1661.

The gates at the end lead into Vernon House, the headquarters of the Royal Overseas Club.

Turn around and walk down Park Place – this could easily be called ‘Club Row’ as besides the two mentioned above, on the left side you pass the large, very anonymous looking and exclusive Brooks private members’ club that dates back to 1764. It’s certainly large as it takes up most of the block, and has its main entrance around the corner on St James’s street. At Number 14 on the other side of the road is the equally anonymous (there’s just a single camera pointing down at the entrance door) and much smaller Pratt’s gentlemen’s club that opened in 1857. It certainly holds on to its traditions – the building has no air conditioning or lifts! I was also interested to discover that all members of staff are referred to as George, so as to avoid confusion (perhaps that shows the advancing age of its members?). This caused a bit of a problem when they employed their first woman – but they quickly got around that by calling her Georgina.

At the end, turn right back down St James’s Street, alongside Justerini & Brook, which had opened in 1749 in the City of London to supply the finest blended scotch whisky, wines and spirits to ‘various aristocratic households’. They have also supplied every British monarch since the coronation of George III in 1761 and are said to have one of the finest wine cellars in the world, supplying many grand hotels and restaurants and representing some of the leading wine makers and chateaux. (Mind you, Berry, Bros & Rudd, which we see later, would probably claim something similar.)

After just 30 or so yards look out for an archway that leads to Blue Ball Yard, into which we now turn. But before you do … take a look back across to the other side of St James’s Street to Number 16 where in a remarkably grand looking building is yet another renowned cigar merchant – James J Fox. It’s the world’s oldest cigar shop and opened here in 1787. They sell some of the most esteemed (and expensive) cigars ever made. Perhaps, not surprisingly, Sir Winston Churchill was a regular customer. They also have a small museum of cigar memorabilia that is free to enter.

Turn up the narrow entrance into Blue Ball Yard, previously known as Stable Yard, which leads to the luxurious Stafford Hotel (nowadays the Stafford London), which you can see at the end.

The Stafford Hotel is certainly unique – and it’s worth taking a look inside. This is actually the rear entrance, so simply follow the corridor through to the reception that is nearer to the main entrance at the front. As you can see, it has a lovely and elegant ‘olde worlde’ charm. The American Bar is open to the public, so you have no problem taking a look inside. The hotel was used by American, Canadian and Free French forces during the Second World War as the many photographs and other memorabilia show. We pass the front of the hotel a little later in the walk.

The row of mews on the left were built around 1742 as stables for the carriage horses (hence the yard’s earlier name) with living accommodation for their grooms above. At one time there were hundreds of mews in London and over the years most have been converted into desirable and usually expensive houses; these have been converted into rather lovely guest suites for the hotel. If you’re visiting in the summer, you’ll appreciate the beautiful flower arrangements here – and it’s also a lovely place to enjoy a drink … though expensive.

Walk back down Blue Ball Yard and continue to the right down St James’s Street for just 50 yards before turning up St James’s Place – on the corner notice the rather unusual, and to me quite fascinating, building that’s home to the Stern Pissarro Gallery, which specialises in Impressionist, Modern and Contemporary art. Notice also the William Evans shop on the other corner – established in 1883 as Gun and Rifle makers (but by the look of window displays they now sell a range of ‘necessities’ for various ‘gentlemen’s outdoor pursuits’. On one occasion when I walked past, I was fascinated by a notice in their window advertising a staff vacancy for an ‘experienced assistant to work in the Gun Room cleaning, maintaining and repairing and selling guns’. I did rather wonder whether they were inundated with applications …

As you walk up St James’s Place on your right you pass a lovely row of terraced houses. At No.3, a plaque explains that this was where in 1848, Chopin left to give his last public performance at London’s Guildhall – he died the following year – whilst a sign at No.8 explains that this was once the home of Francis Chichester, the first man to sail single-handed around the world.

Look down the lane opposite (on the left, by the post box) and in the little cul-de-sac is the Dukes Hotel.

The road now widens and on the left a plaque on the wall of Number 29 tells us that Winston Churchill lived here for several years from 1880.

On your left at the end of the road is the magnificent Spencer House, which was built for the first Earl Spencer and been kept in their family ever since. Ownership has now passed to Charles, 9th Earl Spencer, brother of the late Diana, Princess of Wales, but a few years ago he leased the house to Baron Jacob Rothschild, head of the UK branch of the enormous banking company of that name, who uses part of the house for his private offices. Rothschild has restored the eight state rooms and filled them with the furniture of the period, creating one of the finest neo-classical interiors in Europe. The restoration took over twenty years and Spencer House is said to be the only great townhouse of that period and style to have survived intact.

Turn up to the right (it’s a continuation of St James’s Place) and pass the front of the Stafford Hotel, which we saw earlier. Facing you at the top of the road is the brick built Royal Ocean Racing Club.

However, just past the Stafford Hotel and on the opposite side (next to number 23 and adjacent to a pair of black gates) turn down a narrow alley – ignore the sign saying it’s private as it is actually a public passage; you sometimes see this wording on signs, which is to prevent the owners being sued in the event of injury or accident.

This leads you into the fifty-acre Green Park that is now one of the Royal Parks. Originally used in medieval times as a burial ground for lepers, it was later enclosed by Henry VIII (as was St James’s Park), for him to use it as one of his hunting grounds. Charles II converted it into a Royal Park and sometime later it was named Green Park.

Turn left into Queen’s Walk, (keeping the park on your right) and after about 100 yards you have another view of Spencer House and its rather lovely gardens, though in summer it is difficult to see through the trees.

Next to it is the even larger Bridgewater House and its gardens, where we turn to the left and walk up alongside. Look out for where the iron railings end and you’ll see a small (open) gate – it’s right beside the stencilled ‘no cycling’ sign’ painted on the walkway. The footpath runs up between Bridgewater House on your left and Stornoway House on your right (and I write about both houses next).

This takes you into Clevedon Row – an unusual road as it splits and then runs either side of Selwyn House, which faces you. You can choose which side you walk along – the left side passes the main entrance of the huge Bridgewater House, whilst after passing the entrance to Stornoway House on the right is a short row of rather nice terraced houses.

When you reach the end of the very short Clevedon Row you can’t fail to see the long red-brick frontage of St James’s Palace that stretches ahead on the right.

St James’s Palace is one of the oldest palaces in Britain and it is still the official residence of the Sovereign, although since Queen Victoria’s accession in 1837, no monarch has resided here, living instead at Buckingham Palace. It is still the ‘Court’ where High Commissioners present their ‘Letters’ and Ambassadors are formally accredited.

There’s much more about St James’s Palace in the appendix.

Before the palace, look to your immediate right (but be aware of the armed police who will be keeping a careful watch on you!) and you’ll see the entrance to the courtyard of Clarence House, previously the home of the Queen Mother and now of Prince Charles and Camilla. You can’t actually see the house; what you do see from here is Lancaster House, which was built for the (Grand Ole) Duke of York in 1825 and these days is used for official functions by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

On your left, you pass the Sudanese Embassy (I can’t help wondering why such a poor impoverished country, with millions of its people struggling to survive, needs such an expensive prestigious site.)

St James’s Street is on your left whilst the start of Pall Mall, is straight ahead and runs from here down towards Trafalgar Square.

Using the pedestrian crossing, head across to the other side of St James’s Street, but before you do, notice the beautiful red-brick Dunhill building on the opposite corner. When you get across take a little look inside to see the amazing range of smokers’ requisites and other rather male dominated gifts. You can’t fail to notice (and smell) the glass ‘cigar smoking room’, where there are usually a few gentlemen enjoying a puff on their favourite Havanas. (And the floors above the shop are residential apartments – I imagine a rather amazing place to live, if you could cope with the traffic noise.)

As we walk up St James Street, notice Berry Bros. & Rudd, who’ve been here in these Grade II listed premises since 1698. They are one of Britain’s oldest wine and spirits merchants – indeed, one of the country’s ten oldest companies. What is more, they have been owned by the same family for over three centuries. Their prestigious customer list includes the Royal Family and at one time, the White Star Line, supplying the wines for Titanic’s maiden voyage. However, they started off selling coffee, hence the sign of the coffee mill that hangs outside.

Next comes the hatter Lock & Co., the world’s oldest hat store and one of Britain’s oldest family businesses. They’ve been in existence since 1675, and their customers have included such varied figures as Wellington, Sir Winston Churchill and even Napoleon. Ironically, Admiral Horatio Nelson was wearing one of their hats when he was fatally wounded on his ship Victory in 1805. Their lovely shop front dates back to just five years later, in 1810. They made the first bowler hat in 1850 and both Oscar Wilde and Charlie Chaplin were customers.

Two doors up and a relative newcomer to the street is Lobb’s, who have been making shoes here since 1849 and hold the Royal Warrant for being the shoemaker to the Duke of Edinburgh. They actually make the shoes here in the shop – discreetly pop in to take a look – you can see the craftsmen at work making shoes in front of you. I asked what the cost would be of having a pair of shoes made – they told me that prices started at around £4,200. Hmmm.

And before we turn right down King Street take a look across St James’s Street – Truefitt & Hill, the ‘gentlemen’s barbers’, have been here since 1805.

Turn right down King Street – the rather lovely building on the corner (Number 12) was at one time a rather grand restaurant, but surprisingly is now a very upmarket gym. (Worth sticking your head in if you want to see what a posh gym looks like.)

Fifty yards or so along King Street, turn right down Crown Passage – a very old and rather interesting little lane. On both sides there were once lots of little shops that catered for the local residents’ shopping needs, but most are now cafés and restaurants. This is a good place to stop if you need lunch or just a coffee … there is also a ‘greasy spoon’ café that does an excellent English breakfast, as well as a variety of other fast food outlets. One of the exceptions to the many eating places is Rachel Trevor-Morgan’s wonderful ‘leaning shop’ at No.18. She sells her hand-made hats and headdresses, as well as offering a ‘professional couture service’ – whatever that means. She holds the Royal Warrant as the Queen’s Milliner. The shop appears to be shared with James Lock – we saw the front of their shop just now.

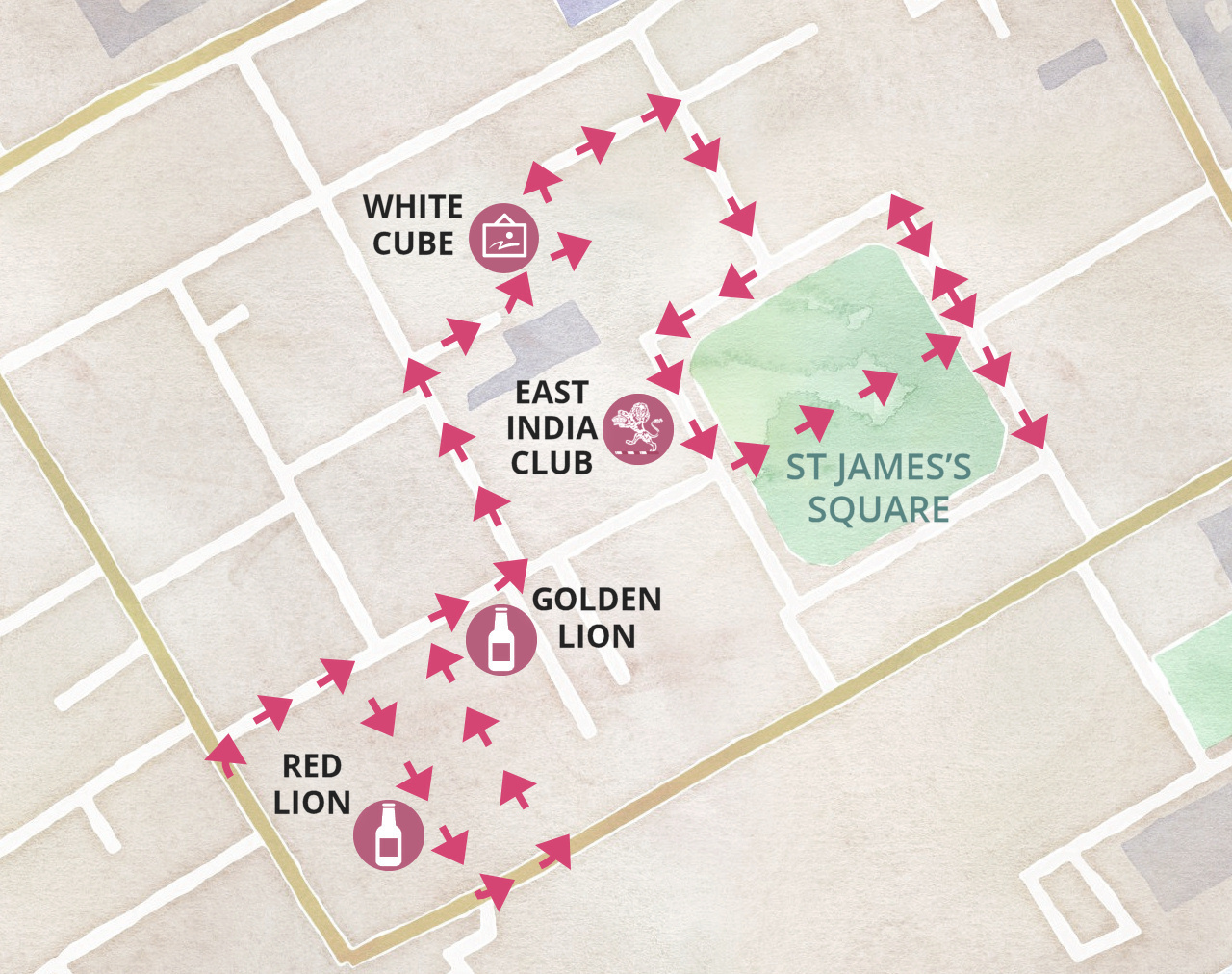

The Red Lion pub near the end of the passage dates from the mid-19th century and describes itself as a “village pub in the heart of St James’s and as much like a typical English boozer as you’ll find anywhere”. Or to use language that’s probably more befitting this posh area of London, “a quaint, quintessentially English inn”. And according to Time Out magazine, it is popular on Saturdays, when the local gentry have retired to the country, with groups of blokes taking part in the fabled Monopoly-board game pub crawl, this being the nearest pub to Pall Mall.

Turn left and you are back on Pall Mall. (If you wanted to take a look in the new Berry Bros. & Rudd wine shop, it’s just twenty yards along to the right.)

After fifty yards we turn left up Angel Court – (opposite the HSBC Bank) – a boring and nondescript lane between modern buildings; just how different can two parallel alleyways be? At the top is another Victorian pub – the Golden Lion. There has been a Golden Lion on this site since at least 1732 and the present building dates from 1897–8.

A plaque on the wall on the left explains that this was the site of the St James’s Theatre that was demolished in 1957, “despite an epic campaign of protest led by Vivien Leigh and Sir Laurence Olivier.” George Alexander, who was manager from 1890 to 1918, staged both Oscar Wilde’s ‘Lady Windermere’s Fan’ and ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’ for the first time.

Turn right at the top – you are now back on King Street – cross over towards Christies, the auctioneers, and we are going to turn left up Duke Street St James’s.

Christie’s

Since the French Revolution this area of St James’s has attracted a number of fine art dealers – and as you walk up Duke Street you will notice there are still plenty here. Christie’s is the best known of all and was started by James Christie in 1767 and has been in King Street since 1823. The building was badly damaged during a bombing raid in 1941, but was rebuilt and the original façade, which fortunately wasn’t damaged, was retained.

On the other side of King Street, opposite Christie’s, you’ll see the entrance to Rose & Crown Yard. A plaque on the wall of the modern building to the right of it (No.28) explains that the Liberal Party was founded here on 6 June 1859.

I’ll also mention that if you were to carry on along King Street for a few more yards, there’s a rather lovely row of terraced houses and above the wrought-iron balcony of the second house, a sign says that Napoleon III lived there in 1848.

But we’re going to turn up Duke Street St James’s, which runs up alongside Christie’s.

Walk up on the right-hand side of Duke Street, passing the rather exclusive art galleries – Number 19 is apparently the headquarters of the Supreme Council of the Freemasons, (as opposed to the Society’s official headquarters in Great Queen Street in Covent Garden). I read that they have given some of the rooms somewhat interesting names; the Black Room, Red Room and best of all ‘Chamber of Death’.

Opposite Thomas Heneage Art Books and the Willow Gallery turn right into Mason’s Yard.

It’s a rather odd little place with an unusual building in the middle. This was once the site of the St James’s and Pall Mall Electric Light Company’s electricity generating station and the White Cube gallery was built here in 2006. The gallery was the first free-standing structure to be built in St James’s for more than 30 years. It’s known for its modern art, exhibiting and selling the works of such luminaries as Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst. (And ‘Mason’? He was a local 18th century victualler).

The red brick building along the right-hand side that has many books in the upper windows, is the London Library – (we see its main entrance shortly.)

Cross to the far-left corner of the yard where we walk through the passage underneath Number 9, but before that, take a look at Number 13 just to the right of the passageway. You’ll see a wooden studded door, which is the Scotch of St James.

Walk along the passageway, which leads into Ormond Yard, then turn to the right down Duke of York Street. As you walk down, you pass the Gaslight Gentlemen’s Lounge Bar and Club. It’s been here since the Second World War and is said to be the most exclusive of all the ‘table dancing’ clubs in Britain. (Not that I would have any first-hand knowledge of such things, of course!) You may have seen the inside without realising it, as it is a popular venue for filming – for example, it appeared in the ‘Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy’ film.

Continue down Duke of York Street and you enter the ‘jewel’ of the area – St James’s Square, with its garden in the centre.

As Beresford Chancellor wrote about St James’s Square in his book devoted to the area: “History and legend will run away with us if I do not restrain my pen, for every house has an interesting history, each has been the abode of some famous personage.” Unfortunately, I don’t think I have quite managed to restrain mine and have included rather a lot of information about this fascinating square.

As I have already mentioned, St James’s Square was the first stage in Henry Jermyn’s development of the area and he planned it to be his pièce de résistance. He was determined to build a small number of houses of ‘substantial character’ around a square with gardens in its centre and he carefully limited the number of plots each builder could apply for, in order to ‘preserve the character of the square’.

The houses were for the very wealthy who wanted to live in close proximity to the Court of St James and were built in the Georgian style of architecture. Once entirely residential, they are now almost all offices, many being the headquarters of notable companies such as BP and Rio Tinto. In addition, the square is home to four famous London clubs: the East India Club, the Naval and Military Club, the Canning Club and the Army and Navy Club.

You arrive in the square at its north side – and we start off by turning right and taking a look at Nos. 10, 11 and 12, which were built in 1736. Nos. 11 and 12 are Grade II listed while Number 10, known as Chatham House, is Grade I.

No.12 was once the home of Countess Ada Lovelace, an amazing woman recognised today as being the ‘mother of modern computing’. A mathematician and writer, Countess Lovelace is famous for being the first person to appreciate the potential of Charles Babbage’s ‘mechanical general-purpose analytical machine’. She could see that it could perform functions beyond that of pure calculation and published the first algorithm to be performed on such a machine. She was also the only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron and his wife Lady Wentworth. Sadly, Ada died of uterine cancer at the young age of 36. One wonders what she might have achieved had she lived longer. She is well worth further study if you ever have time. A good place to start is her biography at the Famous Scientists website.

Next door at No.13 is the High Commission of Cyprus and at No.14 is the London Library (we saw the rear of it just now).

Two doors down from the library on the west side of the square at No.16 is a building with a particularly fascinating history. It was built in 1676 by John Angier, a carpenter cum builder, who also constructed No.7. No.16 has been the home of the East India Club since its foundation in 1849.

Continue on for just a few yards until you reach King Street – on your left a gate leads into the garden (which is open to the public on weekdays), so cross over and walk through the middle of it, passing the equestrian statue of William III that was erected in 1808. Head for the gate on the opposite side and as you emerge into the other side of St James’s Square, walk up to your left.

Many of the houses on this side have been significantly renovated. Numbers 7 and 8, on the corner of Duke of York Street (that we walked down just now) have been completely rebuilt and are now ultra-modern offices that, according to a press article in 2016, were sold for over £200 million.

Turn around and walk back down towards the bottom of the square – as you do you pass No.1 that was purchased by BP a few years ago for what I read was around £115 million.

Cross Charles II Street (you can see the Theatre Royal in the Haymarket at the very end) and a few yards further down, notice the imposing white stone and redbrick Norfolk House at No.31 St James’s Square.

Norfolk House was the London residence of the Duke of Norfolk. He offered it to Frederick, Prince of Wales following his marriage to Princess Augusta and their first child, the future George II, was born here. Much of it was demolished in the 1930s and the building you see today was erected in its place. During the Second World War it became a base for senior Allied army officers and for a while, the headquarters of General Eisenhower. On the last few occasions I have walked past the building it was empty, though I’m sure it will soon be another corporate head office.

At the very bottom, the road joins Pall Mall, which was named after a French ball game of a similar name, similar to croquet, that was played there in the 17th century. Samuel Pepys records visiting it and watching the Duke of York play ‘pelemele’ there.

We’re going to cross Pall Mall, but before you do notice the rather grand building with the columns outside, some 50 yards or so to the right on the other side of the road – this is the prestigious Royal Automobile Club. It’s only for members and by that I don’t mean people who belong to the RAC breakdown service, but a very exclusive members’ club! Like most London members’ clubs, there is a long wait for membership; the criteria to join are very high – and the annual membership fee is huge. So, I suggest you don’t bother even thinking about applying!

The RAC Club is the only private members’ club that I have personally visited. I’ve been fortunate to have been invited there for dinner on two occasions. It has a beautiful interior, with two magnificent restaurants, a spacious rear terrace, over 100 bedrooms for members to stay, as well as leisure facilities that include Turkish baths and a ‘Grecian-style’ swimming pool in the basement. The club was founded in 1897 with the primary purpose of promoting the motor car and its place in society and it was awarded its ‘Royal’ title in 1907 by George VII.

Directly across from where you are standing is another members’ club – The Reform, whilst next door to that is The Travellers, whose early rules stated that: “No one is eligible as a member who shall not have travelled out of the British islands to a distance of at least 500 miles from London in a direct line.”

On the other side of Pall Mall and just to the right is Carlton Gardens, which we now walk down – as you do look through the railings and you can see the Reform Club’s lovely gardens where members can enjoy al fresco drinks in the summer.

At the bottom we turn right into the short Carlton House Terrace. It’s a beautiful terrace of rather grand houses that was built in the 1820s by the Regency architect John Nash. The terraces were part of an extensive redevelopment Nash undertook on behalf of Frederick, the Prince Regent, who later became George IV.

Originally, the land here was used by Nash to build the Prince Regent’s extravagant Carlton House and he lived here for a number of years. However, once he became king, he moved into Buckingham Palace and Carlton House was demolished and the land it occupied, together with its extensive gardens, was used to build the Carlton House Terrace that you now see.

I will just mention here that, as well as building his massively expensive and extravagant house, the Prince Regent also had Nash design him a ‘royal route’ from it to a new park further north. The park became Regent’s Park and the route to it included the construction of Regent Street.

But back to Carlton House Terrace – the houses along it were designed so they had extensive views of the park behind and built in a neoclassical style, stucco clad and with Corinthian columned facades, surmounted by an elaborate frieze and pediment.

We’re going to turn to the right, but before you do notice the houses facing you, Numbers 4, 3 and 2.

The house next door – No.1 – has been the home of several rather influential people, including Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India, Lord Palmerston, and von Ribbentrop, the Nazi supporting German ambassador. It’s Grade I listed, covers 26,000 square feet over several floors and was designed by John Nash in the 1830s.

At this point the street changes from Carlton House Terrace to Carlton Gardens which is basically a small cul-de-sac. There were originally seven houses here, but five have been demolished and replaced by office blocks.

As you walk to the end, notice the statue of General de Gaulle in front of the garden railings on the right. This commemorates his role as leader of the Free French Forces in the Second World War – his headquarters were in Carlton House Terrace.

Directly in front of you at the end of the cul-de-sac are the two remaining houses which, although joined, face different directions.

The right-hand house, No.2, is accessed through the gate, and is the ‘grace and favour’ home of the British Foreign Secretary, whilst No.1 on the left is the office of the Institute for Government, which claims to be the ‘leading think tank working to make government more effective’.

You can’t fail to notice the imposing statue of George VI on your left and a statue of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother behind it. Take the steps beside the statues down to The Mall and as you do, you can see the front – or is it the rear – of the magnificent Carlton House Terrace.

At the bottom of the steps, and on each side, there are two beautiful bronze relief murals which show scenes from the Queen Mother’s life – ranging from her love of horses and horse racing, to scenes of her during the wartime blitz.

Turn to the left, passing the ground ‘basement’ floor of the Carlton House Terrace houses; a row of squat Doric columns supports their terraced gardens and hide what are ‘service’ areas and a car park.

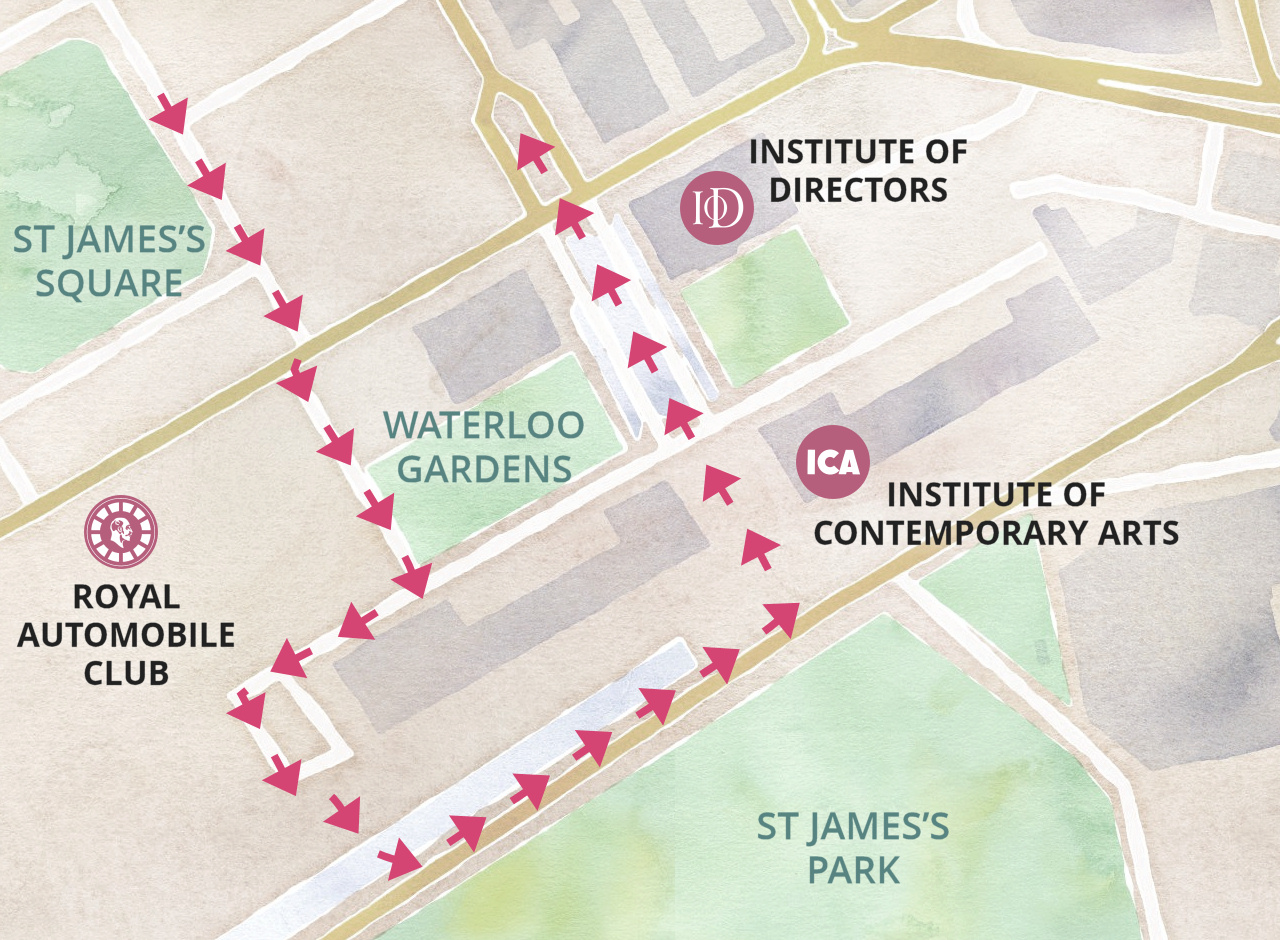

Walk ahead for a few hundred yards and then go up the broad flight of steps on your left … but if you’d like a few minutes ‘diversion’, then just a couple of yards beyond the steps you should see an ‘A-board’ sign’ on the grass promoting the Institute of Contemporary Arts. It’s a rather nondescript entrance, but it’s free to enter and inside there are exhibition galleries, a theatre, two cinemas and a rather nice café-bar, ideal for a coffee, glass of wine or a light lunch or snack.

At the top of the steps is Waterloo Place. Named after the 1815 Battle of Waterloo when Britain finally managed to defeat Napoleon’s forces, it was the finishing point of the Prince Regent’s grand triumphal road that ran from here to Regent’s Park which I mentioned previously. There is so much to see all around you, including more magnificent buildings and numerous statues and memorials. Most prominent is the 110-foot-tall granite column with Frederick, Duke of York (1753-1827), who was Commander-in-Chief of the British Army for many years.

(He was of course, immortalised as the Duke who “marched his men to the top of the hill …” in the nursery rhyme. Although he was said to have been the favourite son of George III, he was regarded as being corrupt, a drunkard and womaniser – yet he has such a prestigious memorial!)

There are too many memorials and statues – mainly dedicated to notable soldiers and explorers – to try listing them all, but if you are interested in seeing ‘who’s who’ then you can wander at leisure and read the many inscriptions.

Waterloo Place is actually situated in the centre of Carlton House Terrace, which also continues to the right. On your left and right are two more magnificent buildings that John Nash had planned, but like a number of the buildings in the area, the final designs were done by the architect Decimus Burton. The one on your right was built as the United Services Club, but it’s now the headquarters of the Institute of Directors, which offers meeting rooms and hospitality for members who have business in London. The one on your left is the Athenaeum Club.

Cross over Pall Mall which runs from left to right and you’ll see several more memorial statues, with three that have important links to the Crimean War. The first is to Florence Nightingale, often known as the ‘Lady of the Lamp’ and depicted actually holding one. To her right is a statue of Sidney Herbert, who was Secretary of War at the time and it was he who asked Florence to go to the Crimea and help nurse the thousands of British troops who were dying on the battlefield from their injuries but given little, if any, nursing or medical support. Having done that, he continued to support her in many ways, and they became great friends.

Behind them is the memorial to the 2,152 officers and privates of the Brigade of Guards who fell during the Crimean War with Russia that lasted from 1854 until 1856.

Finish: Waterloo Place |

We are now at the end of the actual walk, though I will give a choice of routes to take you back to a tube station.

The first is to continue straight ahead, which will take you to Piccadilly Circus. Carry on up Waterloo Place, which becomes Regent Street after you cross Charles II Street, and Piccadilly Circus is at the top.

Piccadilly Circus station is served by the Bakerloo and Piccadilly lines.

The second option is to turn right along Pall Mall, which will take you to Trafalgar Square. From there it’s just a couple of minutes’ walk to Charing Cross station.

Charing Cross station is served by the Bakerloo and Northern lines, and by mainline services. To its south, Embankment station is served by the Bakerloo, Northern, Circle and District lines.

I hope you enjoy the walk.

If you have any comments or suggestions, then please send me a message using the form on the Contact page.

Beneath the shop and surrounding area – even extending for quite some distance under the street – is the network of cellars, many still used today, where they continue to store the thousands of bottles they have in stock. And at one time there was even said to be one tunnel that led across to St James’s Palace. Napoleon III was supposed to have held secret meetings in these cellars when he was living in exile in London in the 1830s.

Beneath the shop and surrounding area – even extending for quite some distance under the street – is the network of cellars, many still used today, where they continue to store the thousands of bottles they have in stock. And at one time there was even said to be one tunnel that led across to St James’s Palace. Napoleon III was supposed to have held secret meetings in these cellars when he was living in exile in London in the 1830s. At one time, Pickering Place was infamous for its illicit gambling dens, but all there is to see now is the courtyard terrace of the rather attractive looking Boulestin restaurant that opened in 1927. It was named after the French chef whose love of food and his country’s cuisine led him to showcase dishes that have now become famous around the world. Boulestin was also the world’s first TV chef. (The restaurant’s main entrance is in St James’s Street.)

At one time, Pickering Place was infamous for its illicit gambling dens, but all there is to see now is the courtyard terrace of the rather attractive looking Boulestin restaurant that opened in 1927. It was named after the French chef whose love of food and his country’s cuisine led him to showcase dishes that have now become famous around the world. Boulestin was also the world’s first TV chef. (The restaurant’s main entrance is in St James’s Street.)

No.5, which faces you at the top of the square, was once the Libyan Embassy and it was here that police constable Yvonne Fletcher was killed by shots fired out of a window in the building in 1984.

No.5, which faces you at the top of the square, was once the Libyan Embassy and it was here that police constable Yvonne Fletcher was killed by shots fired out of a window in the building in 1984.