Updated: 24 February 2023 |

|

Length: About 4 miles |

|

Duration: 3½ – 4 hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

A walk around the Isle of Dogs

INTRODUCTION

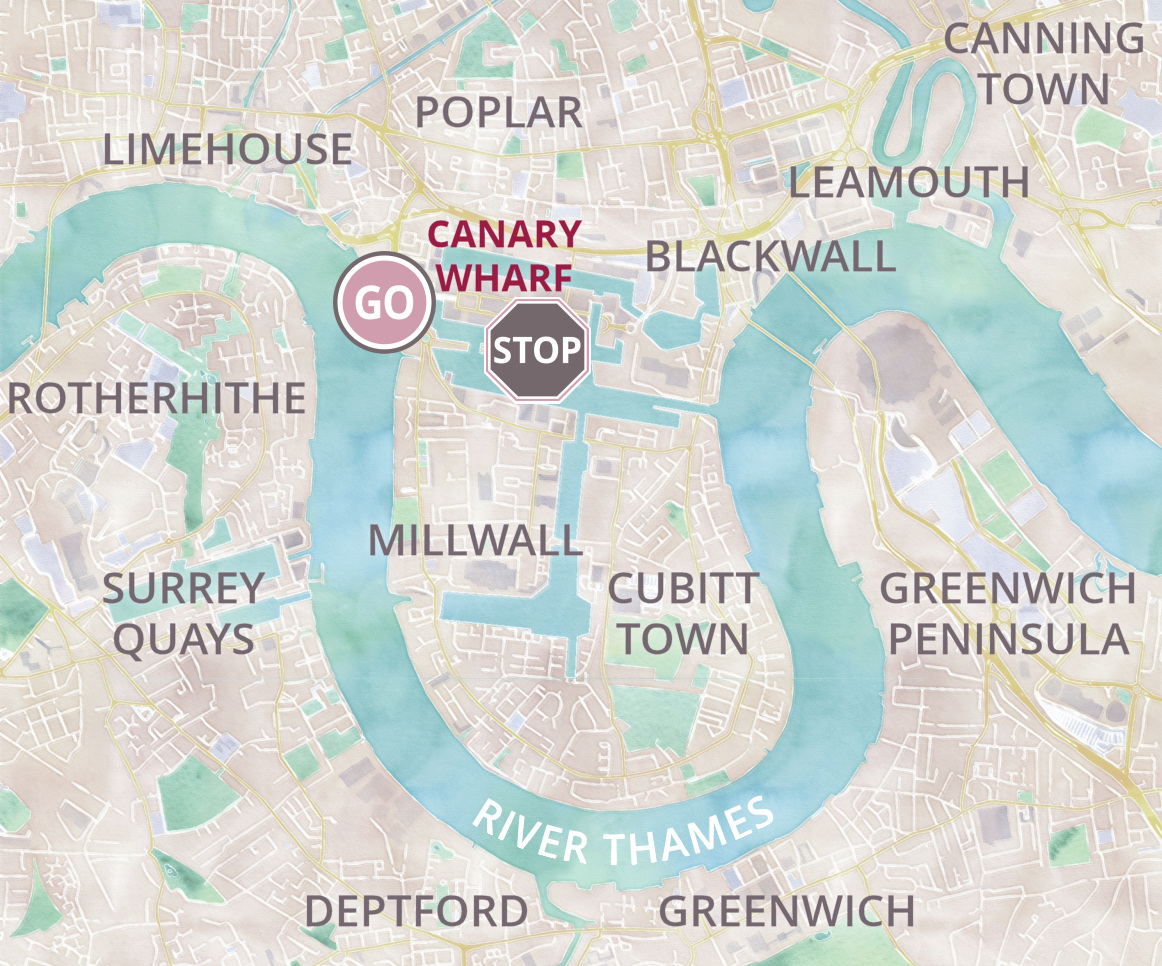

This fascinating circular walk takes you around the riverside path of the Isle of Dogs, once just a large exposed, waterlogged and virtually desolate area of land lying to the east of London. It became the home of the greatest docks in the world and the centre of British commerce, whilst since the development of Canary Wharf it is now at the heart of Britain’s financial life. The walk begins and ends at Canary Wharf.

Please note – I suggest this walk around the island should be done in good weather as much of it is ‘exposed to the elements’ and there aren’t many places where you can shelter from rain or high winds.

Start: Canary Wharf Pier |

|

Finish: Canary Wharf stations |

GETTING HERE

There are several ways to arrive at this point and I list four of them here, giving fairly detailed instructions.

Arriving by Thames Clipper

This is the easiest and most convenient way to arrive if you are travelling down from central London. From Canary Wharf Pier turn right along the riverside promenade (with the river on your right), pass several upmarket restaurants on your left and then what is currently an unfinished building development site and cross over the little bridge. Then start the walk by picking up ‘STARTING THE WALK’ further below.

Alternatively, there are three stations that serve Canary Wharf – on the Elizabeth line, the Docklands Light Railway (DLR) and the Jubilee line.

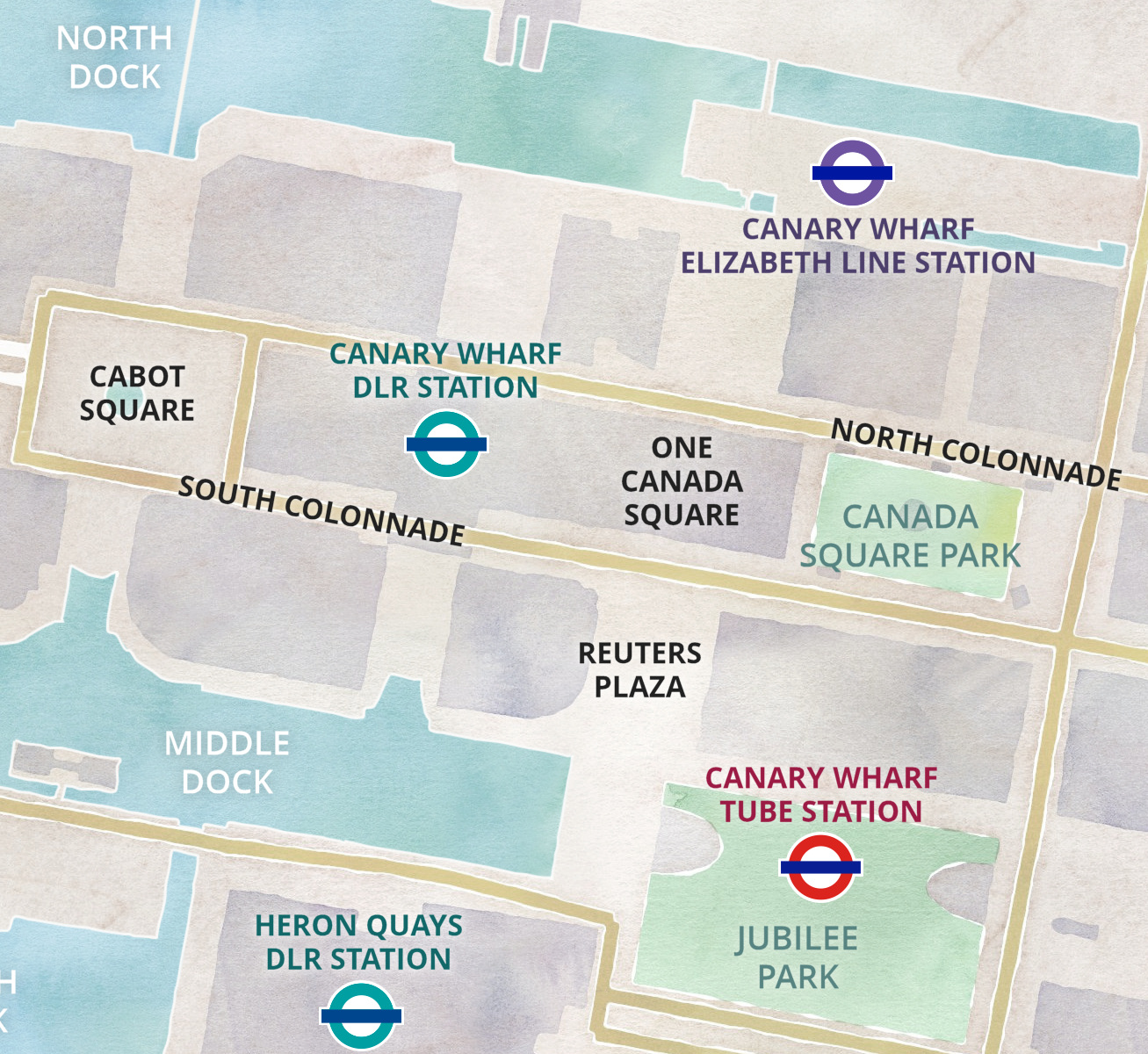

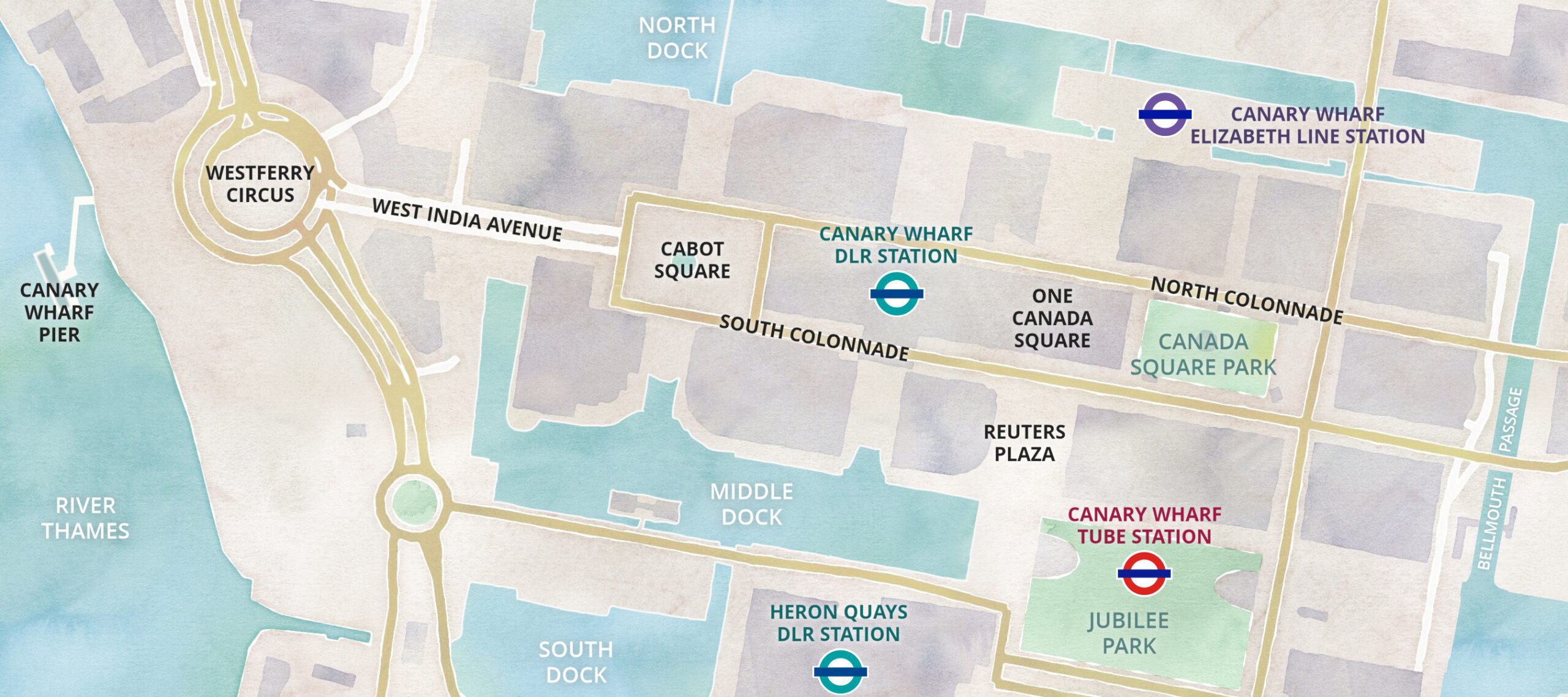

From Canary Wharf Elizabeth line station it’s approximately an eight-minute walk to Westferry Circus, where the walk begins. Follow the signs to Westferry Circus and the Thames Clipper.

From Canary Wharf DLR station – leave the platform (you can alight from the train on either side) and take the escalator down to the lower concourse. There are two main exits from here – take the one marked Canary Wharf Jubilee line station – it’s beside the flower stall, go down the steps and turn to the right, walking westerly along the South Colonnade, away from the Jubilee line station and instead heading for Westferry Circus.

Pass through Cabot Square and continue ahead into the dual-carriageway West India Avenue. It’s easily recognised as there’s pleasant topiary in the central meridian. (You’ll also see several examples of the sculptures that are dotted around the Canary Wharf estate). And in case you wonder, the stone buildings in the middle of the avenue at either end are well-disguised ventilation shafts for the car park beneath.

When you reach the large traffic roundabout at the end, go straight across through the pleasant garden in the middle (notice the unusual gate) and ahead you will see the wide flight of steps that will take you down to the river and the Canary Wharf Pier. (NB – there are well-maintained toilets on the side of the garden).

Turn left at the bottom and continue on as per from the pier above.

From the Canary Wharf Jubilee line station – leave the station via the main exit and at the top of the escalators turn right and immediate left, walking down the side of the dock (which will be on your left). Continue along this path, passing several bars and restaurants until you reach a footbridge (currently with an unusual red circular ‘art installation’ around it, which may not always be there) and turn right up the wide Cubitt Steps.

At the top turn left into Cabot Square and then left again along the wide West India Avenue – and then follow the instructions from ‘Pass through Cabot Square’ in the section above.

If you are arriving by bus (numbers D7 (from Mile End) and 135 (from Old Street & Liverpool Street)) then get off in the dual carriageway West India Avenue. Depending on the direction you’ve come from, either walk forwards or back 50 yards to Westferry Circus (not the Cabot Square direction) then again follow the instructions after Pass through Cabot Square in the section above.

Regardless of which way you choose to arrive at the top of the steps leading down to the starting point at the Thames Clipper river jetty, if you need a cup of coffee or a sandwich, then I recommend the Café Brera, just to the right of the top of the steps.

On the opposite side of the river you will see an old ‘warehouse’ with the words ‘Columbia Wharf’ on it. That is now part of the DoubleTree Hilton Hotel, which at certain times can be a reasonably priced place to stay because it is nowhere near a tube line or rail station. Other than catching a bus, the only way to get anywhere is to catch the hotel’s (non-complimentary) ferry service back across to the Canary Wharf Thames Clipper Pier.

ABOUT THE ISLE OF DOGS

First, three commonly asked questions about the Isle of Dogs –

- Is the Isle of Dogs really an island?

The Isle of Dogs is a low-lying U-shaped peninsular with the River Thames on three sides. However, it’s called an island because when the enormous West India Docks were built here, a channel was cut across from one side of the peninsular to the other to enable ships to access them from both the west and east sides. This made it, technically at least, an island and the name has stuck. - Where did the ‘Dogs’ come from?

Some sources say the name came from the hunting dogs that both Edward III and Henry VIII kept there, whilst others say it came about as a result of the Dutch engineers who were brought over from Holland to help drain the area – and from Dykes came the word ‘Dogs’. - Where did the name Canary Wharf name come from?

It seems generally accepted that the name Canary Wharf was simply a result of ships from the Canary Islands unloading their cargoes of tomatoes and later bananas at one of the wharves here and the name simply stuck for the whole of the 97-acre site!

The dramatically changing fortunes of the Isle of Dogs

The change in the fortunes of the Isle of Dogs has been spectacular. For hundreds of years the Isle of Dogs was virtually uninhabitable marshes, known as the Stebenhethe (i.e. Stepney) Marsh, with apparently just one dwelling which was known as Chapel House.

Show more history …

Until the start of the 19th century the population was still small, and the land used just for grazing cattle. However, in 1802 the open countryside was replaced by massive docks, built here to cope with the phenomenal increase in trade between London and the rest of the world. Tall ships and later steamers would unload cargoes of sugar, rum, timber and exotic fruits from the West Indies and elsewhere.

As a result the population grew from less than a hundred people at the beginning of the 19th century to over 20,000 at the start of the 20th.

During the Second World War, London’s docks were amongst the top targets for the German Luftwaffe; and quayside warehouses, factories – and sadly thousands of local people’s homes – were destroyed. Once hostilities ended, rapid reconstruction soon got under way and business began to boom once more. However, this revival was short-lived. In the 1960s and 70s larger ships and containerisation, as well as constant labour difficulties resulted in ships moving to the new, larger and better equipped container ports such as Tilbury. The decline of the docks was nearly as rapid as its initial growth and their subsequent closure resulted in abandoned warehouses, derelict factories and very little work for the local people.

It soon became a ‘forgotten Island’ and by 1981 the population of the Isle of Dogs had dropped to below 15,000. It was then that the Conservative government established the London Docklands Development Corporation (known as the LDDC) with the aim of regenerating some 8½ square miles of this area of the East End of London.

New major access roads were built; the DLR (Docklands Light Railway) was opened, and later the Jubilee line and London City Airport were constructed. Huge investment also went into improving the standard of social housing, opening new schools, medical centres and much more.

The Isle of Dogs became an ‘Enterprise Zone’, offering tax breaks and freedom from many planning restrictions, and this led to many new businesses being established. These ranged from printing and distribution companies through to the greatest success story of all – finance. Indeed, Canary Wharf is now known throughout the world as one of the leading centres of financial trade, and I explain more about how this came about in the appendix.

Show less

![]()

Please note – there is an optional walk around the actual Canary Wharf site (the financial district and ‘hub’ of the island) at the end.

STARTING THE WALK

The walk starts at the jetty of the Thames Clipper River Bus docking station. Start walking downriver, passing several expensive restaurants on your left followed by a large area of waste ground. (Building seemed to start several years ago but then halted and nothing appears to have happened since.)

Behind it are three tall buildings – the first is Newfoundland Point, a new, ultra slim and diamond shaped 60-storey residential apartment building – the narrow shape is as a result of it being squeezed onto a very small portion of land. (Its unusual criss-cross ‘bracing’ is designed to keep it up.)

The smaller building with the striking sloping glass frontage is ‘One Bank Street’, the new office of the Société Générale, a French multinational investment bank. Dwarfing it is the monolithic, 784-ft Landmark Pinnacle. With 75 floors, this will be the tallest residential building in Europe – no other has every floor designated for residential accommodation.

Cross the South Limehouse Entrance Lock Bridge (also known as the City Arms Bridge because of a nearby pub) over the South Dock Canal. The five wheels you can see set into the small cabinets on the bridge control the opening and closing of the inlets from the river.

Originally called the City Canal, it was opened in 1805 by the Corporation of London who had hoped to make big profits by charging ships a toll to use this shortcut and so avoid the huge bend in the river, which in the days of sail could sometimes be difficult due to the change of wind direction. The canal turned out to be a financial failure and was sold to the West India Dock Company in 1829 to provide access to their South Dock. However, it was sealed off to shipping some years ago.

Notice the red brick single storey building that faces you; this is the West India Dock Impounding Station, which was built in 1930 to maintain the water levels in the dock complex. The pumps automatically switch on when the water level drops and needs to be ‘topped up’. It also helps prevent the docks from silting up, previously a significant problem, as whenever the lock gates were opened then mud would be swept in from the River Thames which would then need to be dredged to maintain access for ships.

After crossing the footbridge over the canal turn right and continue on down the riverside path, passing a number of apartment buildings. The first one is called Cascades and was the first residential apartment building in this part of Canary Wharf. At 20 storeys (194 feet), when it was built in 1988 it was the tallest apartment building for miles around, and its height was only permitted because of the number of even taller office blocks being built nearby in Canary Wharf. Indeed, it’s actually hard to imagine that until fairly recently, both this and the Anchorage apartment building next to it, rather dominated the local landscape.

Cascades was designed by Rex Wilkinson of – and don’t you just love the name of this company – Campbell Zogolovitch Wilkinson Gough. Built of brick and concrete, it was clearly designed to have a degree of nautical influence – the portholes and the tiny concrete balconies, which were perhaps designed to be like the lookouts on the edge of the bridges on ships. But the use of the different coloured bricks and stonework do make the building look slightly more interesting, although it is beginning to show its age. I assume the name came about because of the way the right side of the building ‘cascades’ down, which you don’t see until you are almost past it, and I think it looks like a ski jump. Notice the unusual looking ‘penthouse’ apartments at each level on the ‘cascade’.

Both Cascades and the Anchorage apartment building next to it which partly protrudes over the river path, were built on the site of the C & E Morton’s factory which opened here in the 1870s, producing a wide range of foods including jams, pickles, custard powder, cans of preserved fish and meat and even hair oils.

At one time Millwall, the name of this area, was a hive of shipbuilding activity – sail, steam, wooden and iron ships all being constructed here. To supply these shipyards there were ironworks, rolling mills, mast makers and ropemakers. Some of these industries employed vast numbers of people. Millwall ironworks is said to have employed around 4,000 men and boys in the 1860s. In 1808 a local company, Brown Lennox and Co., came up with the idea of using link chain to replace the hemp rope mooring lines on ships, which they patented. They became the sole manufacturers of chains for the Navy for 100 years, the longest ever unbroken Admiralty contract.

In the 1860s shipbuilding on the Thames experienced a massive financial collapse that threw thousands of people out of work. Shipbuilding, heavy metal industries and rolling mills, began moving up to places such as Tyneside in the northeast and Scotland where there was more land and even cheaper labour.

In place of them came manufacturing businesses, chemical works, food processing factories and light-metal industries, lured by the cheap labour and easy access to the river and docks.

One of the major commodities in Millwall Docks was grain, and a 13-storey ‘Central Granary’ was built in 1903. Long pneumatic tubes, both resembling and known as ‘elephant trunks’ stretched down into the ship’s holds to suck the grain up into hoppers where it was weighed. It was then transferred by moving belts either into the granary or one of four colossal silos which stood on the quay.

Next on your right is West India Pier with Cuba Street on the left. The pier was built in 1875 by the West India Dock Company, later becoming a stop on the steam-boat passenger service to Westminster. Badly damaged in the Second World War, it has apparently been purchased, but what its future use will be, nobody seems to know.

The next buildings are part of a massive apartment complex, collectively known as the Millennium Harbour. I like the design of the first two or three buildings, with the two sides at the top leaning towards each other. They were built when land prices here were still quite low – these days developers couldn’t afford to waste valuable land space like that, where another building could have been squeezed in between them. The top of each building, where the two sides almost seem to touch, are apparently very spacious duplex penthouse apartments. Each has three bedrooms, three bathrooms and a spectacular double height galleried reception and dining area, with terraces on all sides. I also like the steel balconies, a feature that has been adapted for other buildings along here.

As you continue along, notice some of the original iron mooring posts still left where, in the past, ships would have tied up to be unloaded. On some posts you can still see the original details – for example, ‘Bean Patent’, made by T Summerson Sons Ltd., Darlington.

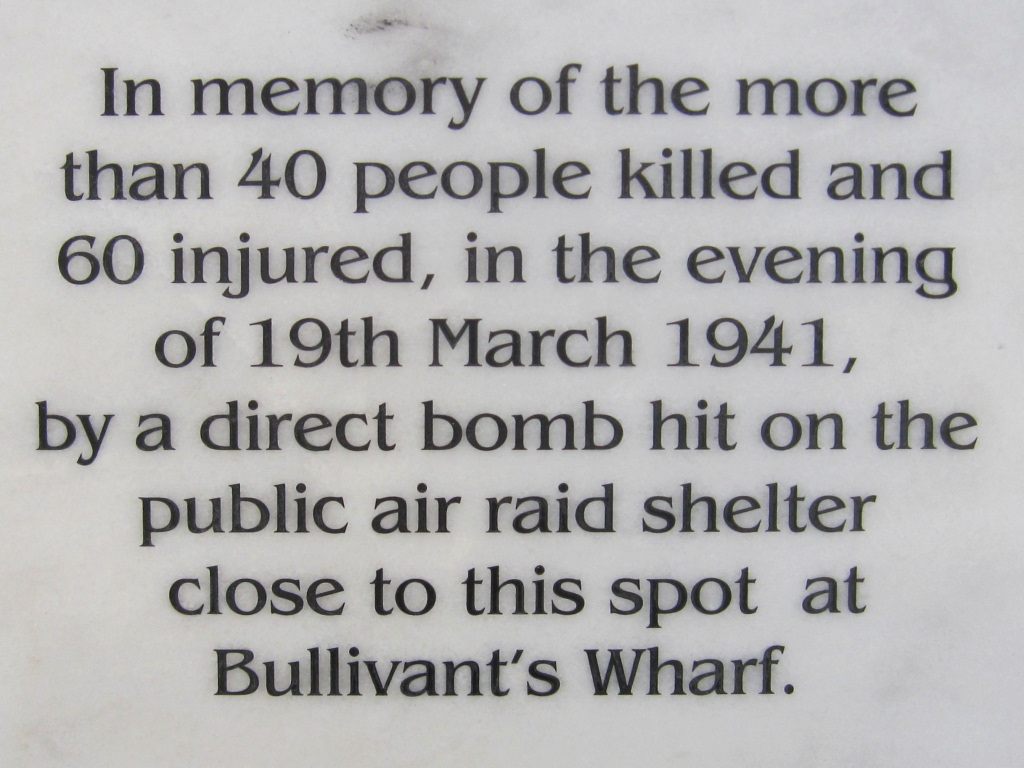

At Bullivant’s Wharf, where there had been a major rope works since 1883, you’ll see a row of four tall metal poles sticking up from the riverside railing and on the small brick wall a plaque that commemorates a terrible disaster that occurred here during the Second World War when over forty people were killed.

Notice the two aluminium sculptures beside the path. They are made to rotate so the shape of the composition is always changing.

Shortly after we reach the Sir John McDougall Gardens, where a sign here tells us we’ve walked three-quarters of a mile since leaving Canary Wharf and that it’s another mile and a half to Island Gardens at the very bottom of the Isle of Dogs and the point at which we begin walking back up the east side.

By the late 19th century the owners of the factories and wharves that were built alongside the river’s edge began lobbying to have the riverside path, which we are now on, closed to the public. Although a public right of way, they eventually had their way and it was indeed closed. Some years later a campaign was organised for a park to be built to enable local people to have access to the river. This succeeded and it is where we are now. It was named after a member of the famous McDougall flour milling family who owned an enormous factory nearby.

However, sadly as you will shortly see, we still have to turn inland and walk down the busy Manchester Road for half a mile or so before we can continue on the river path.

On the opposite bank of the Thames you can see the entrance to what used to be the extensive Greenland Dock complex.

Continue on past the park on the riverside path and you come to another massive apartment complex that’s made up of a number of enormous buildings. Called New Atlas Wharf, its roofs have an unusual circular aspect to them, looking as though they could be roof gardens, although I haven’t yet been able to find out whether they are.

On your right are stone steps that give access at low tide to a wide expanse of shoreline. There’s even a sandy beach in places at low tide. But be careful – these steps can be very slippery – so despite the risk of sounding like a health and safety official – use the handrail! If you do go down (and it’s worth doing so if you can) notice how well built these old riverside retaining walls are, despite the wear and tear as a result of the tides and storms over the years.

After another 100 yards or so, and just before the path actually ends, you need to turn left down a narrow lane, which becomes the wider Arnhem Place. The large Arnhem Primary School will be on your right, whilst on the left you can better appreciate how enormous the New Atlas Wharf complex actually is.

At the bottom turn right onto the Westferry Road. Unfortunately, we now have to take this rather boring busy road for nearly half a mile. It runs right around the Isle of Dogs, from Westferry Circus, but when it reaches the bottom and goes up the east side its name changes to Manchester Road.

As the road goes up a slight incline, on the left is what is currently (2020) a huge 15-acre development site. It was formerly the Westferry Print works, the largest in Europe where each day many millions of newspapers, including the Daily Telegraph, Financial Times and Daily Express were printed, having relocated here from Fleet Street. It opened in 1984 and was one of the early successes of the London Docklands Development Corporations campaign to bring new business to the area. However, as the value of the land the site is on has soared in recent years, the land was sold to a developer and in 2011 the printworks were closed and relocated elsewhere.

The planning application for the site includes the development of both residential and commercial buildings of between four and thirty storeys, a secondary school as well as 70% of the land being preserved as open space for local people and residents. Fortunately, the old cranes you can see on the site have been preserved and will become a feature on the new site. However, at the time of producing this walk the site is the subject of a major political and planning row, so nobody knows what the outcome will be.

A few yards further on, at the top of the incline, is the Docklands Sailing Centre, built on the edge of the Millwall Dock. It was set up in 1989 by the London Docklands Development Corporation and the Sports Council at a cost of just over £1 million and enables both local people and school children to learn and take part in various water activities. It’s a great use of this expanse of water which was the Millwall Outer Dock – part of the extensive Millwall Dock complex which was created in the 1860s. Fortunately, when the dock closed it wasn’t filled in but was instead preserved.

If for any reason you want a shorter walk, then you can follow the quayside around the dock back to South Quay and then to Canary Wharf.

Access into this dock from the Thames was via a massive lock, the remains of which you can see on the right. When it opened in 1867 it was the largest lock in London (80ft wide and with two chambers, one 246 feet and the other 198ft.) Badly damaged by bombs in the Second World War, it was refurbished in 1950, but finally closed just a few years later and filled in. It’s worth taking a walk down to the river (though it doesn’t lead anywhere) to see the old machinery on tracks. Of particular interest is the part of the former hydraulic ram that used to close the massive lock gates; high pressure water would push the piston up the tube that moved the wheels up the railway track that you can see. This then set the pulleys moving that pulled the chain at the far-right end, which in turned opened the lock gate. Hope you’ve got that!?

Continue on along the main road, passing several shops on the right and on the left a row of dockworkers cottages that escaped being destroyed during the intensive bombing raids in the Second World War that did so much destruction in this area.

Next on the left is an unusual looking building that was previously the St Paul’s Presbyterian Church. Built in a Romanesque-style using coloured stone and brick that’s said to resemble a ‘scaled-down’ version of the cathedral in Pisa, Italy, it’s a Grade II listed heritage building. It was built in 1856 for the Scottish iron workers who had come to find work in the nearby shipbuilding yards, many of whom were Presbyterian. The church was paid for by John Scott Russell, a Scottish engineer and shipbuilder who worked with Isambard Kingdom Brunel in building the Great Eastern ship nearby. And apparently one of the aims of the church was to “rescue the workers from the degrading habits into which they were sinking.”

Time to stop for a snack?

I recommend the Hubbub café/bar in the former Presbyterian church that is now a theatre and arts centre.

Time to stop for a snack?

I recommend the Hubbub café/bar in the former Presbyterian church that is now a theatre and arts centre.

The church has closed and is now an arts and community centre called The Space. On the first floor is an excellent café/bar called Hubbub. It’s open all day for coffees and light meals, whilst in the evening it becomes a very nice informal bar and restaurant.

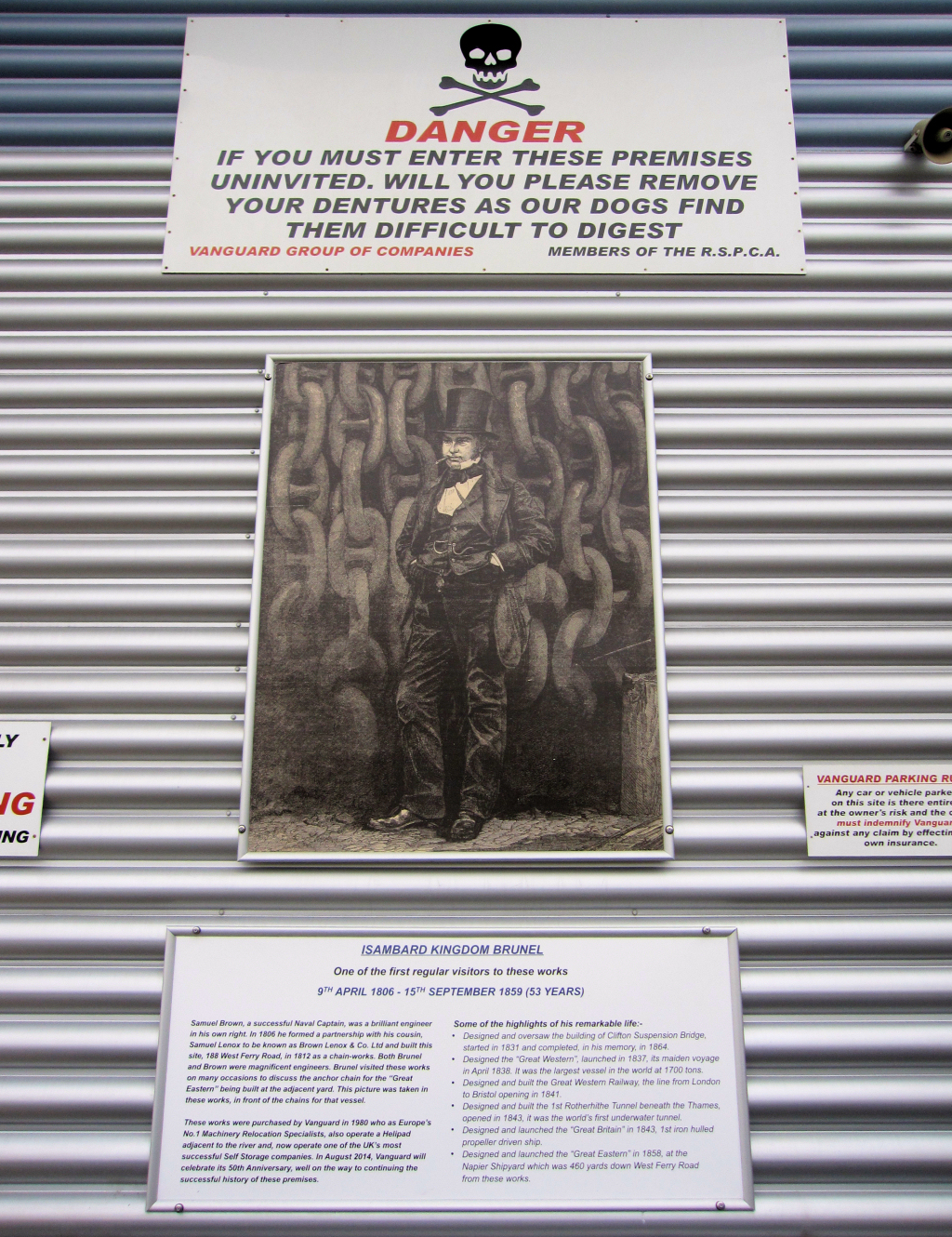

Continue down Westferry Road for another couple of hundred yards, but as you pass the entrance to the Vanguard Self Storage depot on the right take a look at the signs. One on the fence outside warns that the spikes on top are coated with anthrax, whilst another on the actual building advises that if you do trespass, ‘please remove your false teeth as our guard dogs find them difficult to digest’! There is also a huge picture of Isambard Kingdom Brunel on the outside of the building and a sign giving more information about him, which I have reproduced in the pop-up box below.

Almost opposite is the modern-looking St Edmund Catholic Church which only opened in 2000. It was built on the site of an earlier church that had opened in 1874 to serve the thousand or so Catholics who were living on the island by that time. However, to save money during the building of the original church, only limited piling was carried out, which led to significant structural problems, and its eventual demolition and the building of the church you see today in its place.

Cross over Mast House Terrace and take the next right up the small road – it doesn’t have a name, but a sign clearly explains it takes you back to the Thames Path.

At the top pass through the gate under the block of flats and turn left along the riverside path. After the busy main road, the next stretch is a welcome relief, with trees and greenery that separates it from the blocks of apartments behind. There are even seats where you can relax and enjoy the view across the river, though unfortunately, the view on the other bank isn’t that special – but within half a mile that will certainly change.

Pass the Bering Square residential development and you come to the Masthouse Terrace Thames Clipper Pier. (And if for any reason you’ve had enough walking, from here you can catch the ferry back to Canary Wharf, Tower Bridge and central London).

On your left is the preserved historic site where Brunel’s massive Great Eastern steamship was built and launched in 1857. The site is now an attractive open green space, though you can still see the original timber baulks of the slipway, which surprisingly were only rediscovered a few years ago. The ship was built at the adjacent Russell’s shipyard, now Burrell’s Wharf, which we pass next.

The disastrous and prolonged launching of the ship in November 1857 was just the beginning of the Great Eastern’s ill-fated career. (And I’ll just mention here that when the ship was launched it was named the Leviathan – it wasn’t renamed the Great Eastern until later). It was four times bigger than any other at the time and so large – 680ft long and almost 19,000 tons in weight – that Brunel was concerned that launching her in the traditional ‘bow first’ manner its momentum might have resulted in the ship hurtling straight across the river and crashing into the opposite bank.

His solution was to launch it sideways and he built a new slipway, which is where we are now standing, and designed a system of hydraulic rams that were attached to heavy iron chains to push it into the water at high tide. The first attempt failed – it moved for just a few inches before the friction produced by her great weight caused her to become stuck. This was rather embarrassing as thousands of spectators had come to watch.

Charles Dickens watched that first attempt at launching the Leviathan (SS Great Eastern) and wrote:

“A general spirit of reckless daring seems to animate the majority of the visitors. They delight in insecure platforms; they crowd on small, rail housetops; they come up in little cockleboats, almost under the bows of the great ship. In the yard they take up positions where the sudden snapping of a chain, or the flying out of a few heavy rivets, would be fraught with consequences that they have either not dreamed of, or have made up their minds to brave. Many on that dense floating mass on the river and the opposite shore would not be sorry to experience the excitement of a great disaster, even at the imminent risk of their own lives. Others trust with wonderful faith to the prudence and wisdom of the presiding engineer, although they know that the sudden unchecked falling over of or rushing down of such a mass into the water would, in all probability, swamp every boat upon the river in its immediate neighbourhood, and wash away the people on the opposite shore.”

“A general spirit of reckless daring seems to animate the majority of the visitors. They delight in insecure platforms; they crowd on small, rail housetops; they come up in little cockleboats, almost under the bows of the great ship. In the yard they take up positions where the sudden snapping of a chain, or the flying out of a few heavy rivets, would be fraught with consequences that they have either not dreamed of, or have made up their minds to brave. Many on that dense floating mass on the river and the opposite shore would not be sorry to experience the excitement of a great disaster, even at the imminent risk of their own lives. Others trust with wonderful faith to the prudence and wisdom of the presiding engineer, although they know that the sudden unchecked falling over of or rushing down of such a mass into the water would, in all probability, swamp every boat upon the river in its immediate neighbourhood, and wash away the people on the opposite shore.”

Further attempts were made but it was nearly three months before the ship, with the help of an easterly wind and a high tide, was finally launched. I’ve written more about the Great Eastern in the appendix.

Next we pass Burrell’s Wharf, which as I explained above is where the Great Eastern, and many other ships, were built. Shipbuilding stopped here in 1888 and relocated to new yards on the Clyde and Tyne in the north of the country, and this site became the Burrell’s Colour Factory.

When the factory closed in the mid-1980s, the buildings were turned into the well-preserved Grade II listed residential complex that you see today. There’s a pleasant raised courtyard garden with a fountain, trees and benches – and a gigantic anchor. Behind it is the original Plate House, previously known as Gantry House, which was built for the fabrication of the iron plates for Brunel’s Great Eastern. The huge plates were moved around the factory by overhead cranes on gantries, hence the alternative name. Plate House now houses a swimming pool and leisure facilities whilst to the right of it is Beacon House, with its restored original chimney. It’s all beautifully restored in what I’ve seen described as an “odd fusion of warehouse and church styles, with an austere Romanesque turret.”

Next to it is Maconochies Wharf, which in the mid-1980s became an extensive self-build development. The idea for it came about as a result of the concerns of a local doctor regarding the great number of flats being built in the area by speculators and which he didn’t think were suitable or affordable for local families. He helped set up the Great Eastern Self-Build Housing Association, involving many local people, some of whom were in the building trade. The development has subsequently won a number of awards, and thanks to the variety of the different styles of homes is considerably more pleasant than many other developments along the riverside. (The name ‘Maconochie’ comes from a firm of food manufacturers and merchants who were previously on this site).

Then follows a row of pleasant three-storey houses with wooden balconies, and the trees along this stretch make it quite pleasant, giving welcome shade on a hot day.

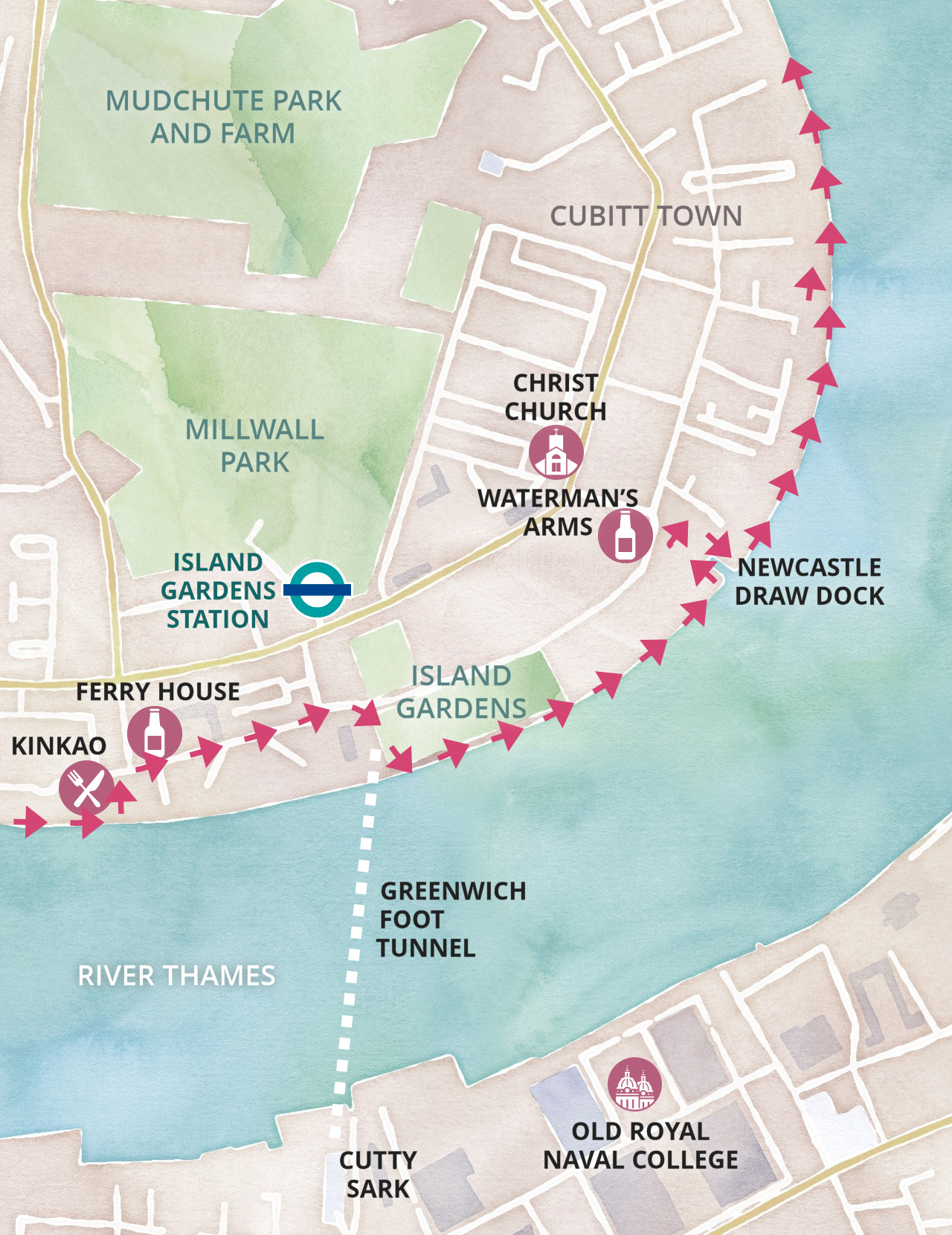

Next, you’re about to see one of the real jewels of this walk – the view across the river of the historic maritime town of Greenwich. First you see the masts of the Cutty Sark, in front of which you should be able to see a circular walled brick building with an interesting domed roof. This is the Greenwich entrance to the Thames Foot Tunnel, (you see the north bank entrance shortly), whilst in the distance above the trees you should be able to see the Greenwich Observatory.

The riverside path ends at the Kinkao Thai restaurant. I can recommend it as an excellent place to stop for a coffee, light lunch or to return to in the evening for dinner. It has a lovely outside terrace where you can sit and enjoy your drink or meal with the fabulous view across the river.

Walk down the side of the restaurant, turn left and then right, passing the Ferry House Inn on the corner. A sign announces that this is the oldest pub on the island – ‘circa 1722’. It is called the Ferry House because this was where people would wait to catch the Potter’s Foot Ferry across to Greenwich. The ferry is said to have been here since at least the 14th century and a couple of hundred years later in the 17th century Samuel Pepys records using it on several occasions when he was working for the Admiralty. (The ferry stopped running after the Blackwall Tunnel opened in 1897 and the Greenwich Foot Tunnel in 1905).

Continue straight ahead along Ferry Street (though there doesn’t appear to be a sign with the name on it), passing the Felstead Wharf buildings on your right. At the end is a slipway, known as Johnson’s Draw Dock, with the nondescript premises of the Blackwall and District Rowing Club, alongside it. This was the site of the old North Greenwich railway station, built in the 1870s and which had a steamboat pier from where a ferry service operated to and from Greenwich. It departed every 20 minutes and was used by the workers who lived on the south side of the river. Whilst the one-way fare was only one penny, this was a lot of money to the low paid workers, and when the tunnel opened the ferry soon stopped running.

Carry straight on ahead along Saunders Ness Road until you reach the entrance on your right into Island Gardens. (‘Saunders Ness’ refers to a spit of land or promontory – it’s from the old English word naes – which in turn comes from the French translation of the word ‘nose’, “le nez” – and refers to the land that curves round the bend of the Isle of Dogs at this point. The origin of the name ‘Saunders’ is unknown, but it appears on a 16th century map of the area.)

The Island Gardens public park opened in 1895. It was built on land owned by the Greenwich Seamen’s Hospital and before becoming the park it was just open land, sometimes used as a rubbish dump. It was eventually taken over by the London County Council who turned it into the public park we see today. (And as an aside, there used to be a gibbet here where pirates would be hung and left hanging for several days. It had been chosen because it was such a visible spot, the idea being it would act as a deterrent to other would be pirates).

The walk continues through the park along the river side, but it’s a delightful place to sit and take a break, particularly on a summer’s day as there’s a cafe selling light refreshments which has outdoor seating. There are lovely views across the river to Greenwich and Sir Christopher Wren, the architect of the Royal Naval Hospital, said that this was the finest view of his ‘masterpiece’. The Venetian artist Canaletto clearly agreed as it was from here in around 1752 that he painted his masterpiece ‘Greenwich Hospital from the North Bank of the Thames’.

Looking from right to left you see the domed cupola roof of the Greenwich entrance of the foot tunnel, which I mention below. Next is the Greenwich Pier, built in 1863, always with a cluster of trip boats in front, and behind is the Cutty Sark. In centre stage are the majestic buildings of the Royal Naval Hospital, built by Christopher Wren in 1699. Between them, and on the hill behind, is the Old Royal Observatory, also built by Christopher Wren, but some fourteen years before the Hospital. Also in between, but just behind, is the Queen’s House, built in 1616 by Inigo Jones. Further to the left is the Trafalgar Inn, famous for the past two hundred years for its meals of whitebait – which it still has on the menu today. The enormous brick building further again to the left is the former London Transport Power Station, built in 1906, whilst just to the right of it you can see the former Trinity Hospital Alms Houses, built in 1613.

As you entered the gardens you couldn’t have missed the entrance to the Greenwich Foot Tunnel. It opened in 1902 to link the Isle of Dogs to Greenwich. The tunnel is 1,215 feet long with a 60ft shaft and around 90 steps on either side. However, there is a lift, which has just been renovated and those with a claustrophobic nature will be pleased to know that not only is it large but also has glass doors! But for those of a nervous disposition, it’s a sobering thought that the roof of the tunnel is just 13 feet below the bed of the river. And I’ve been told – but never actually experienced myself – that in the tunnel at low water you can hear ships as they pass overhead. (And whilst I wouldn’t recommend trying to squeeze in a visit to Greenwich on this walk – you are only about halfway around the island at this point – it is a fascinating place to visit.)

The walk continues through the gardens and up the east side of the Island to Canary Wharf, but if you’re running out of time or getting tired then you can catch the DLR from the Island Gardens Station. It’s just a couple of hundred yards down Douglas Lane that’s immediately opposite the entrance to the park – you can see the station’s futuristic roof from here. Several buses also stop here, including the 135 which goes to Old Street, via Canary Wharf, London Bridge, Monument, etc.

To continue the walk, carry on alongside the river through the gardens. The path passes the Lucinda Wharf apartment complex, cleverly designed so that as many as possible have balconies and river views. Follow the path down the side of the slipway, which was originally the Newcastle Draw Dock – (a draw dock is where boats can be drawn up out of the water and either unloaded or worked on under its waterline).

On the corner in front of you is the Waterman’s Arms, built by William Cubitt as part of his redevelopment of the area. It’s now Grade II listed and in August 2020 became a pub and boutique hotel.

Look down Glenaffric Avenue that runs down the side of the pub and you can see the attractive Parish Church of Christ and St John, which was also built in 1854 and paid for by William Cubitt.

Indeed, the area you are now in is called Cubitt Town, which is named after him. Besides being a civil engineer, William Cubitt was a highly successful builder and businessman who became a Member of Parliament and in 1861 the Lord Mayor of London. He had realised that the growing numbers of workers in the docklands, particularly those close to his early business interests in the Isle of Dogs, needed somewhere to live. He set about developing homes for them, laying out the streets we see today that followed lines of the former drainage ditches. Much of what he built was destroyed during the Second World War, and subsequently the local authority built a number of homes on the site. More recently many private homes have been built here, some with excellent views of the river.

Walk down the far side of the slipway to get back to the river. The walk now passes a small 1970s social housing estate – slightly unusual and rather nice to see ‘proper little houses’ rather than the monumental apartment blocks we have been passing.

We now head up the east side of the Isle of Dogs to the north. Soon the former Millennium Dome, now the O2 entertainment complex comes into view. Next a former warehouse that was called Cubitt Wharf blocks the path, which we have to walk around. Now converted into apartments, it was once used for cleaning, crushing, grinding and storing rice, grains and seeds by the London Rice Mill Company. Later it was owned by the Cotton Seed Company and used for the refining and manufacture of oils, including cotton-seed oil.

Being right on the water’s edge these apartments must have fabulous views, though the opposite bank is fast beginning to be redeveloped. There has even been talk of a vast cruise liner complex, including hotels and shopping centres being built there, so the current view of the hills of Blackheath on the horizon will probably one day be obscured.

Walk around the rear of the building, turn right through the car park then back up the other side of the building and carry on up the river path.

On the opposite bank you can see Morden Wharf and to its left the IFS Cloud aerial skyway – looking very out of place as a result of the bends in the river. The photo above was taken at the end of January 2020. The East Greenwich No.1 gas holder has since been dismantled.

Next you come to two white pillars with a set of steps in front of them. This is Dudgeon’s Wharf and it is a memorial to five members of the fire brigade and one civilian who lost their lives in a huge explosion that took place here on the 17th July 1969. Workers had been busy demolishing the long disused oil and petrol tanks with oxy-acetylene burners when a fire started in one of the tanks. The fire brigade were called, but the fire was out by the time they arrived. A number of firemen climbed on to the rim of the tank to pour water inside, as an extra precaution, but unfortunately a demolition worker was still working below with his oxy-acetylene burner. The tank exploded, killing five firemen and one demolition worker.

Behind is another huge housing and apartment complex, and some of those on the river’s edge look well designed and attractive, especially those with the wooden trellis and shrubs. Many even have gardens fronting on to the Thames Path.

Looking ahead up the Thames you can begin to see the towers of the extensive new developments taking place at Blackwall, a mile or so further north on the river.

Go through the ‘anti-motorbike barrier’ passing the bland development called the Millennium Wharf – however, they do at least have private access to the pier/jetty. I like the single-storey restored brick-built building next to it, again now converted into apartments. It is part of the enormous London Yard development, which has been built on a site that was originally a shipbuilder’s yard and where ships such as the HMS Resistance were built. The yard later concentrated on building torpedo boat destroyers and then iron bridges that were prefabricated and shipped overseas.

When shipbuilding finally ended, it became the packing factory for C.E. Morton’s, the jam, soup and pickle manufacturers whose main site we saw at the beginning of the walk at the top of Westferry Road. However, during the Second World War it did revert to a manner of ship building, as the Mulberry Harbours that were used for the D-Day Invasion of France were built here.

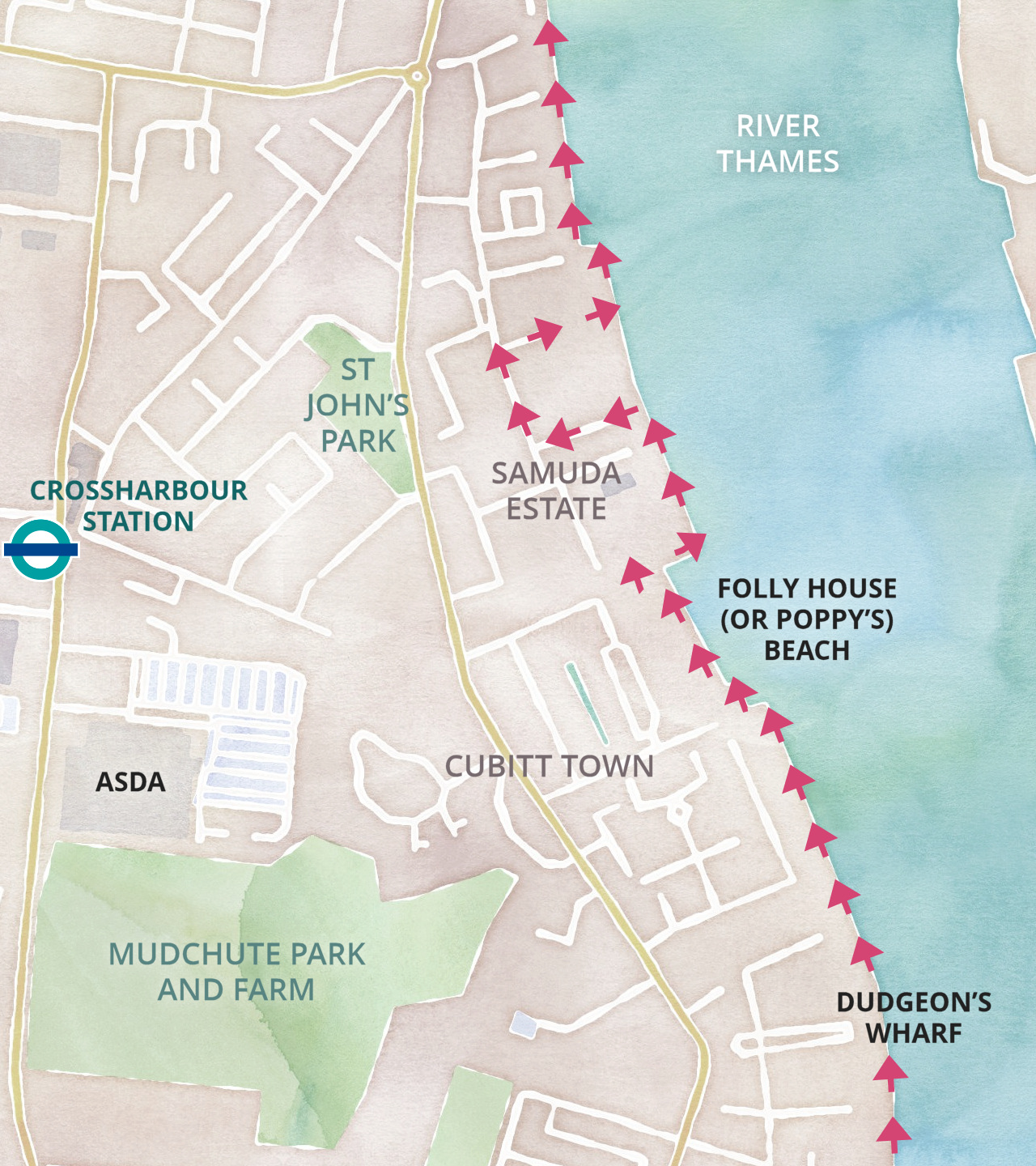

Another ‘anti-motorbike’ barrier then the path goes in and around a rather unusual inlet – all part of the London Yard complex – and which the developers agreed to turn into a ‘beach’ with a garden behind it. It’s actually got a name – ‘Poppy’s Beach’ – and is a popular place with locals on a warm sunny day. It’s also known as Folly House Beach, after a home – later a tavern and then shipbuilders’ offices – that stood nearby until the 1880s.

Continue back to the river, but only for a short stretch as I explain next. The big tower block looming ahead is Kelson House, part of the Samuda Estate, which we walk through next. The estate is currently undergoing a massive refurbishment which I’m sure will help to improve its appearance, but it does mean that the riverside path is likely to be closed until this has been completed.

The Samuda Estate seems to me to be a poorly designed and soulless 1960s social housing development, but of course I guess we have to remember that it probably didn’t seem that way when it was built. It was on what had been a shipbuilding yard of that name and when that closed the wharf was broken up into small units and used for a huge variety of different purposes. One of those was the Motor Packing Company, where cars and lorries that were built in factories in Coventry and the Midlands were driven here, dismantled, packed into crates and finally shipped abroad where they would be reassembled.

Because of the renovation works currently (2020) taking place, the next part of the walk may be a little difficult, and you will probably need to walk ‘inland’ for a couple of hundred yards through the car park and then turn right along Stewart Street through the middle of the estate. Continue on until you reach the pedestrian lane (with no name) that’s adjacent to River Barge Close. Walk up it and then turn left along the lane in front of the row of terraced houses. (There is a sign that says, ‘River Walk’.)

At the end of the short path you leave the river for just a few yards and walk around the rear garden/parking of a couple of riverside houses – and then immediately turn up the lane with the high security railings alongside the colourful brick building. It’s not until you turn the corner and see its frontage that you can fully appreciate this unusually designed ‘Egyptian-styled’ building. And as I’m sure you won’t be able to work out what it is then I’ll explain that it’s the Isle of Dogs Stormwater Pumping Station.

It was built in 1989 to help prevent flooding on the island; high water as the result of heavy rainstorms is pumped up into a huge ‘surge tank’ and this then drains into the Thames. What appears to be the cone of a jet engine is actually what expels the sewer gases from the pumping station. Built by John Outram, who called it a ‘Temple to Summer Storms’, it has won a number of awards and has subsequently been given a Grade II* listed building status. I have also read somewhere that it’s been designed to be both ‘explosion and earthquake proof’ and able to last for over 100 years.

And for those interested in reading more about it, this Historic England web page will give you more information.

The O2 is now closer than ever over on the south bank, whilst you now pass some attractive dwarf cone-shaped trees and bushes that front some unusual white semi-circular apartment buildings with well-kept lawns and gardens. The complex is known as Pierhead Lock, (I’ve also seen it referred to as Galleons View) and I think it is well designed, with the main building resembling an ‘ocean liner’, whilst another reminds me of a Bournemouth seaside hotel.

Pass the three parking bays, (the path looks as though it could be private, but it isn’t), and then the attractive building that now houses the offices of the Canal & River Trust. This is the organisation that’s taken over the responsibility from British Waterways for maintaining many of the canals and rivers in Britain. Immediately ahead is the striking blue lift bridge which has the Trust’s name on it, which we turn right and walk across.

The bridge, which was built in 1969, crosses the entrance to Blackwall Basin that links with the West India South Dock and from it you get an excellent view of the skyscrapers in Canary Wharf’s financial district.

Once you’ve crossed the bridge, then after just 50 yards turn right into a short street of terraced houses – the sign says ‘Riverside Pub’ – and at the bottom you will see The Gun – one of the oldest of the many riverside inns on the Thames.

It’s a famous and delightful pub that has a long wooden terrace overlooking the Thames and a small garden terrace overlooking the entrance to the West India Dock’s South Dock. Now possibly as much of a restaurant as a pub, you walk from the street into what was once the bar, but the white linen tablecloths and napkins indicate that it’s now for dining – and quality dining too. (For some years it has been a favourite for discrete expense account lunches for business people working in Canary Wharf – at one time I noticed they had an offer of a complimentary limo service to pick you up from your office and take you back after your meal. The food is said to be excellent – and I loved the way that one morning I saw two of the chefs outside on the garden terrace cutting herbs from the high-rise beds for that day’s lunch. That’s what you call fresh!)

However, please don’t be put off if you just fancy a drink. There is a bar for those just wanting a drink with cosy rooms at the rear, as well as the terrace and garden. It is after all a perfect spot for enjoying a quiet pint or glass of wine and a chat.

Leave the Gun and turn right along Coldharbour, a very historic street that was once part of an ancient track that went around much of the island. Whilst there are now modern apartment buildings on the left, most of those on the right are much older, though several seem to me to have been spoilt by what I think to be ‘inappropriate conversions’ – Concordia Wharf for example. I also feel that the ground level car park under some is incongruous and unnecessary.

The building at Number 19 was once the Blackwall Police Station (notice the old lamp – though no longer blue) still in position over the steps. Before the station opened in 1894 the police had been based in an old ship moored in the Thames. If you’re wondering why the entrance is at the top of a flight of steps, it is because beneath the building a ‘boat dock’ was built which enabled the police to sail from the river straight into and under the middle of the building. The station closed in 1978 and was subsequently converted into apartments.

Number 15 (on the right in the street view above) was built in 1844 on the site of an earlier 1770 building and was the home and workshop of a joiner and mast maker and is listed because of its largely intact interior. Numbers 7 and 5 were built around 1809, whilst No. 3, the lovely Georgian house with the pillars, was built ten years later. And the reason for it being called ‘Nelson House’ is because this is where the Admiral himself once lived.

Finally, at No. 1 is ‘Isle House’ – with the steps up to the raised front door, presumably to avoid flooding. It was built by John Rennie the Younger in 1825 for the Dockmaster of the Blackwall Docks. The full-height bow windows at the rear allowed excellent views of the river and the entrance to the lock. According to the Rightmove website, this magnificent six-bedroomed house with outstanding views, was sold in 2015 for £2,500,000.

And how times have changed. These last three houses were later lived in by Port of London police families, until in 1935 when a 21-year lease was granted to a housing association and they were divided up into rooms for letting to weekly tenants.

At the end of Coldharbour turn right into the busy dual-carriageway Preston’s Road and then immediately right down the steps alongside what was a lock. (On my first few visits here the gate was always open, but the last time I visited it was unfortunately locked. However, if it is open then walk to the end of the path and follow the ‘jetty’ to the end where you get an excellent view of the river frontage of the houses you saw just now in Coldharbour – and you can see what an excellent view too that both Nelson and later the Dockmaster had.)

Looking downstream from the lock is the Northumberland Wharf Waste Transfer Station, where the gigantic yellow crane loads rubbish into steel containers that are then lifted on to barges to be transported downstream to the aptly named ‘Mucking’ further down the Thames estuary in Essex, (though I understand a new site may now be used). Transporting London’s rubbish by barge – six thousand tons of it a year – has resulted in stopping over 400 lorry trips a day through London’s crowded streets.

Continue on down Preston’s Road – but as you do notice the massive new development taking place on the other side of the road. This is Wood Wharf, the latest ‘extension’ to Canary Wharf.

A short way down Preston’s Road cross over Raleana Road, but as the walk now continues on down the other side of Preston’s Road we need to cross over. However, as this can be a very busy with fast traffic, I suggest you carry on for a few more yards and cross over at the pedestrian crossing.

Having done so, walk back up for a few yards until you reach the start of the long, high brick wall. (All of London’s docks were built with these very high walls in order to improve security).

Go through the narrow entrance gap in the wall, turn right and follow the pleasant tree-lined path which leads into and around Poplar Dock, now a marina for residential boats.

The walk takes us around three sides of the marina, passing two wonderfully preserved electric 6-ton cranes, built by Stothert & Pitt in Bath. Follow the path around the slipway inlet and when you reach the top end of the basin, follow the path along Myers Walk, which runs alongside the Blackwall Basin. (If you look over to your left you can see where it originally led out to the Thames through the lock that we passed earlier.)

Blackwall Basin was the first impounded, or non-tidal, dock entrance ever built. It served as an enormous entrance lock, allowing ships to pass through from the Thames into the basin at high tide. The lock gates would then close and the vessels could remain afloat in the basin after the tide had receded, passing through into the main docks when convenient without affecting the water level in the docks. Blackwall Basin has been designated a ‘Barge Village’ by the Canal & River Trust, who administer it, and the boats you see here are mainly on permanent moorings.

Continue along the path, passing a large but fairly well landscaped apartment development on your right and the towering skyscrapers of Canary Wharf looming ever larger.

Go up the iron staircase at the very end of the path and cross to the other side of the dual carriageway. This is the approach road from the east into the Canary Wharf financial district – you are now in a very different world and the scenery really changes. On your right you can see the yellow roof of the massive Billingsgate Fish Market. (You can often smell it as well as see it). It used to be situated alongside the Thames in the City of London, just a few hundred yards up from the Tower of London, but like the Covent Garden Fruit and Vegetable Market, (and soon to be the case with the Smithfield Meat Market as well) it moved out of London as a result of both the rising value of the land it was on as well as the problems of traffic and access. However, it is soon to move again, this time further out into Essex, as even the value of this land has soared.

Start walking towards Canary Wharf, passing the security control post – security is something they take very seriously here, as a result of past terrorist attacks. It goes without saying that being the financial ‘nerve centre’ of Britain, it is always a potential target for terrorists.

Immediately past the security post is Cartier Circle, and on the little grass central traffic reservation (with an unusually laid out topiary) is an art installation comprising of seventeen sculptured bronze posts standing up to 35 feet high.

Over on your left you can see the immense Wood Wharf development site, which I mentioned previously.

You are now in the ‘Canary Wharf Estate’.

Continue ahead, with the bulky One Cabot Place tower looming ahead, and follow the road around to the right into Churchill Place. On your right is One Churchill Place, a 32-floor skyscraper that’s the head office of Barclays Bank which opened in 2005. It was originally planned to have been 50-storeys but was reduced following the terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre in New York.

Cross the steel bridge over the canal that links the North and South Docks and keep walking down what is known as the North Colonnade. On your left is Canada Place (a sign says ‘Third Space’, which is a high-end fitness club), which contains a large Waitrose store, whilst the building on the right are the offices of the accountants KPMG (and I like the stainless steel or wire sculptures in the angled gap between the buildings).

Turn left along the front of Waitrose but after a few yards cross over to the other side and walk into the entrance of Canada Square. As you enter the square, on your right you’ll see the exclusive Ivy Restaurant.

The gargantuan 50-storey One Canada Square that towers over you was built in 1991. It’s still the most prominent and prestigious building in Canary Wharf. (Until the 72-storey Shard opened in 2012 it was the tallest building in Britain.) It was originally planned to be even higher but concerns about the risk to planes landing at nearby London City Airport meant it had to be reduced by five floors.

Its architect, César Pelli, said he based the design on a combination of the World Trade Centre in New York and Big Ben in London (which since the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee should be called the Elizabeth Tower.) It’s clad in stainless steel and has a distinctive aircraft warning light on its pinnacle. I’ve put more information about the building, the architect and Canary Wharf in general in the appendix. Meanwhile, here are some fascinating facts and figures about One Canada Square:

If you take a 360 degree look at all the surrounding buildings, you can see why this is now regarded as the financial heart, not only of London and Britain, but Europe as well, and rivals New York and Hong Kong.

Plenty of things happen in this square – from early November until late February it becomes a 1,300 square feet ice rink, with an attractive skating path taking you through the trees and lights, whilst in the summer a cinema screen shows major sporting events and there are occasional outdoor music events. As you can see there are several bars and restaurants around the side of the square, and on a nice day it can be a very pleasant place to sit and enjoy a drink. However, at the end of the working day on weekdays it can be quite chaotic with huge numbers of people enjoying a pre-travelling home drink or two.

And for Dr Who enthusiasts I’ll mention that One Canada Square was the headquarters of the Torchwood Institute. The building’s height enabled it to reach the radar black spot that was later determined by the Institute to constitute an anomaly in space and time, in reality a breach into the Void. (And not being a Dr Who fan, I really have no idea what this is all about it – I’ve just read it on a Wikipedia page). It also adds that to gain access to the offices you had to approach one of the receptionists on the ground floor and say, “Mr Sands”. (And I wonder how fed up the real staff got with Dr Who enthusiasts saying that to them!)

Finish: Here, optionally |

HEADING BACK TO CENTRAL LONDON

We’re almost at the end of the walk now. However, below I give several options, as some people may have had enough walking or run out of time and need to get back to central London. Others though may like to see a little more of Canary Wharf, so below this section I offer a short continuation of the guided walk of the area as well.

- By Thames Clipper

From Canada Square leave from the left-hand side and turn right along South Colonnade and keep walking through Cabot Square and all the way back to Westferry Circus. (If you leave from the right-hand side of the square, then turn left and walk to the far end of North Colonnade, through Cabot Circus and continue until you reach Westferry Circus.) - By Jubilee line Underground

Leave Canada Square via the left-hand side and turn right and continue walking and turn left down the wide flight of steps that lead to Reuters Plaza. Keep walking ahead and you will see the station on the left. - By DLR

To get to the DLR station from Canada Square Plaza I’d suggest you walk straight into the entrance of the One Canada Square building – walk around the left side of it and leave via the exit on the opposite side to which you came in. Go through the doors and down one level and keep walking ahead until you reach the DLR station atrium. - By bus

Leave Canada Square on the left-hand side and along the South Colonnade you will see several bus stops.

A NOTE ABOUT SHOPPING AND REFRESHMENTS

To many people Canary Wharf is all about banking, high finance and skyscrapers. But it is much more than that. For a start there over four ‘subterranean shopping malls’ – Cabot Place, Canada Place, Jubilee Place and Churchill Place – which are all connected. Together they have almost 300 shops, bars and restaurants. And not just any old shops, but high-end stores such as Alfred Dunhill, Hugo Boss, Tiffany & Co, as well as the usual high-street brands like Boots, WH Smith and Waitrose. For dining the list is equally as extensive. French, Spanish, Italian, Japanese – many of which offer outdoor ‘alfresco’ dining.

If you’d like to take a look before you leave (or continue the walk) then walk straight ahead into the ground floor of One Canada Square, and take the stairs down on the left-hand side.

CONTINUING THE WALK AROUND CANARY WHARF

Leave Canada Square by walking into the ground floor of One Canada Square with its capacious marble lobby and then leave via the doors on the right-hand side into the North Colonnade.

If you look across to your right you can see the HSBC Tower, which can accommodate 10,000 staff. Notice the pair of lions outside that ‘guard’ the entrance. Apparently, these are exact copies of the two statues that were made for the Hong Kong office of the bank. (I understand that in Chinese culture the lion is regarded as the divine beast and it is thought that it can ward off evil spirits.)

Cross over the North Colonnade where facing you is a wide covered passageway leading into the futuristic Adams Plaza Bridge and into the new Crossrail Place.

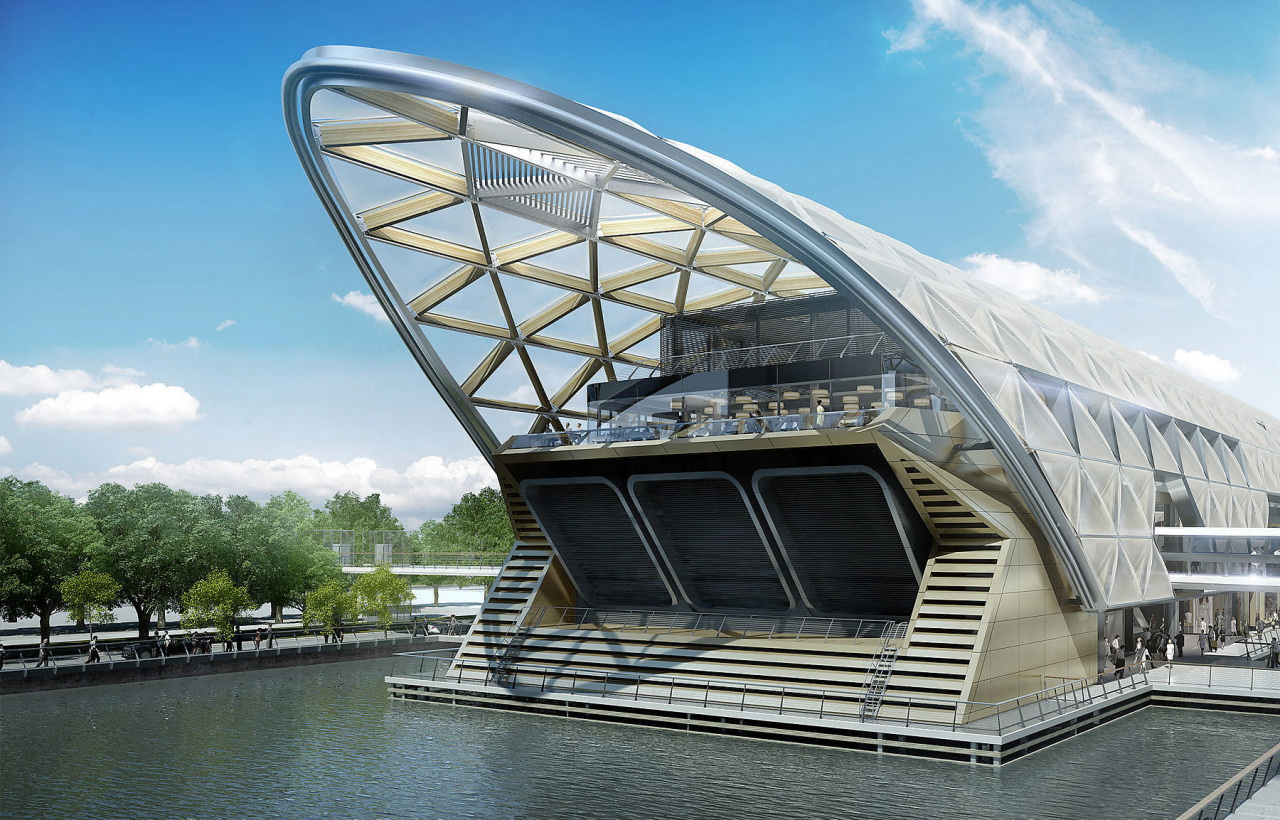

This is Canary Wharf’s Elizabeth line station and equally futuristic. It’s a multi-level development, distinctive due to its ‘bubble-wrap’ covered roof. The complex is far more than just a station, which is on the bottom level; there are over 100,000 square feet of retail and leisure facilities spread over several storeys with shops, restaurants, a cinema and an amazing roof garden.

It was designed by the world-famous architects Foster+Partners, who also designed the Kai Tak cruise terminal in Hong Kong (also situated in a ‘dock’ and said to have similar features). They also designed the Jubilee line’s imposing Canary Wharf station and the HSBC Tower, whilst away from Canary Wharf some of their other spectacular buildings in London include the Gherkin and City Hall.

The station and complex is built into a giant concrete box which was sunk down into a section of the West India dock and twenty-one million gallons of water had to be pumped out. A similar process was used to construct the Jubilee line Canary Wharf station, which we see at the end of the walk. There are several floors beneath ground level – on the lowest are the platforms, whilst the ticket hall is on the floor above and then there are two floors of retail and leisure opportunities.

However, it’s the roof garden that I find particularly spectacular, which is accessed via the escalator on your right. With flowers, shrubs and trees from all over the world it has become an amazing public space. In addition to the garden, there is a large bar-restaurant at each end – the ‘Big Easy’ and the ‘Giant Robot’. There’s even an ‘open’ sixty-seat performance area that’s used for a wide variety of events.

The garden is situated almost directly on the Greenwich Meridian line and it’s split into the two hemispheres with flowers, plants and trees that are native to each on the respective sides.

I suggest you follow the right-hand path through the garden to the end – there are lots of little side paths and benches to sit and enjoy the atmosphere along the way. At the end is The Giant Robot, a large, open-plan bar and food court. From its open terrace at the rear you can see how much land is still waiting to be developed. The long building that runs adjacent is currently the Billingsgate Fish Market, though it will be moving out from here to a new site further east, enabling its now very valuable thirteen-acre site to be redeveloped.

Walk back down the other side of the garden towards the ‘Big Chill’ – a huge restaurant, with a small bar – and leave via the escalator or stairs back down two floors, (one below the one level you came in on) and follow the passage that will take you across to the opposite quayside and turn left.

You are now on West India Quay. Walk under the DLR station, pass the tall Marriott Hotel on the right and the two restored cranes on the left. Unmissable next is the line of magnificently preserved warehouses – generally looking very much as they would have looked over 200 years ago when they were built.

Whilst many of the upper floors contain apartments, the ground floors now contain restaurants and bars, most with ample outdoor terraces on the quayside, very pleasant on nice days to enjoy a drink. The exception is towards the end of the row, which is now the Museum of London Docklands. It is a fascinating place – on the ground floor there’s a book and gift shop and a very good café and toilets. On the upper the upper floors are the exhibits and displays. You could easily spend half a day here, but if you’ve just completed the whole of this walk it is unlikely that you’ll have time to visit today. On the quayside outside is a spherical green buoy which would have been used to mark the site of a wreck, whilst the black and white chequered buoy would have marked a navigational channel.

Also at this end of the dock are several moored boats, one of which is London’s only floating church – St Peter’s Barge. A weekly Sunday morning service as well as some lunch time talks are held here.

If you look back at the Crossrail station you can better appreciate how it has been built into the dock and what a feat of engineering it is. The three large rectangular shapes hide the ventilation fans for the subterranean station.

Cross over the steel pontoon-footbridge to the other side of the quay and walk up the steps to Wrens Landing. (On the right at the top are public toilets).

The excellent bronze sculpture is called ‘Two Men on a Bench’ and is by artist Giles Penny. Cross over North Colonnade and up the steps into the terraced centre of Cabot Square. The fountain in the middle is attractive and – a piece of fairly useless information – the height of the water jets is controlled by a discreet wind gauge on the top of one of the tall lampposts on the side of the square. The unusual but attractive colourful circular glass panels form the cladding for the four ventilation shafts for the car park below. There is also a large steel sculpture entitled ‘Couple on a Seat’ by Lynn Chadwick.

Finish: Here, optionally |

If you’ve now had enough and want to get back to central London via the DLR, then from the raised terrace of the centre of the square turn left and walk down the steps and into the entrance of the shopping centre. Keep walking and after a couple of hundred yards you will come to the atrium beneath the station.

However, if you’d like to see a little more or catch an Elizabeth line or Jubilee line train, then leave the square by the steps on the opposite side from where you entered – cross over South Colonnade and walk down the steps facing you. At the bottom turn left along Mackenzie Walk – it runs along the side of the South Dock. Pass the little inlet and you are in what is called Reuters Plaza, so named because the Reuters company’s offices are in the large building on the left (as you look at One Canada Wharf), with an electronic news ticker tape display wrapping around the building.

I like the art feature called ‘Six Public Clocks’ designed by Konstantin Grcic. Each one is based on the iconic Swiss railway clocks and mounted on a post. Look carefully and you’ll notice that each of the twelve faces shows a single and different numeral.

One of the many sad results of the lockdown during the 2020/21 coronavirus epidemic was the closure of the Smolinsky’s restaurant. This renowned London institution had a very popular restaurant to the right of the entrance into One Canada Square, but on my last visit (August 2020) it had closed, as had several other bars and restaurants in the area. My hope is that when things eventually get back to some sort of ‘normal’, we may see these opening up again.

Finish: Canary Wharf Jubilee line station |

For those needing the Jubilee line station, then walk away from Reuters Plaza and facing you at the end of the South Dock you will see its arched entrance canopy on the left.

But before you enter the station, just take a look back at the towering One Canada Square building and remember that it could be laid lengthways – with room to spare – into the Jubilee line station. This thousand-feet long station is built within a ‘concrete box’ in a drained dock, similar in some ways as the more recently constructed Crossrail station we saw just now. However, this doesn’t have a roof garden, but instead above it is a very pleasant landscaped park, the largest open green space within the Canary Wharf Estate.

If you are in the park, then the only clue that something is below are the glass canopies – these cover the three entrances into the station and draw light down into the concourse below. Walking into the station’s main entrance is stunning, with a bank of escalators leading down into an enormously spacious concourse. However, to actually catch a train you go down to yet another level.

(Finally, in case when you see it you think you have seen it before, then you may have as it was used in the film ‘Love Actually’.)

For the Elizabeth line station, walk up the wide flight of steps beneath the One Canada Place building that towers above you, proceed up to the first floor, walk through the lobby and leave by the exit on the opposite side. You’ll see the footbridge that’s signposted to the Elizabeth line station.

I hope you have enjoyed the walk. If you have any comments or suggestions then I’d love to hear them.

If you would like more information on any of London’s docks, as well as some excellent photographs (many of which are for sale) then take a look at londonsdocks.com.

Fishermen Dredging off the Isle of Dogs, 1838, ‘W.H.F.’, Wisbech & Fenland Museum

Fishermen Dredging off the Isle of Dogs, 1838, ‘W.H.F.’, Wisbech & Fenland Museum

The sign gives Brunel’s dates of birth and death (9th April 1806 – 15th September 1859) and lists some of the highlights of his remarkable life, which included designing and overseeing the construction of the Clifton Suspension Bridge; the SS Great Western, SS Great Eastern and SS Great Britain, each revolutionary and the largest vessels afloat at the time, the Great Western Railway, from London to Bristol and the Rotherhithe Tunnel beneath the Thames – the world’s first underwater tunnel.

The sign gives Brunel’s dates of birth and death (9th April 1806 – 15th September 1859) and lists some of the highlights of his remarkable life, which included designing and overseeing the construction of the Clifton Suspension Bridge; the SS Great Western, SS Great Eastern and SS Great Britain, each revolutionary and the largest vessels afloat at the time, the Great Western Railway, from London to Bristol and the Rotherhithe Tunnel beneath the Thames – the world’s first underwater tunnel.

The name ‘Poplar’, which was given to this area, was as a result of the many poplar trees that were on the site before the docks were built. They like damp soil, so grew well alongside the River Thames where they were thought to act as windbreaks. And as an aside, the BBC television series ‘Call the Midwife’ is based in Poplar, and the opening scenes show a terraced street with a ship moored at the end.

The name ‘Poplar’, which was given to this area, was as a result of the many poplar trees that were on the site before the docks were built. They like damp soil, so grew well alongside the River Thames where they were thought to act as windbreaks. And as an aside, the BBC television series ‘Call the Midwife’ is based in Poplar, and the opening scenes show a terraced street with a ship moored at the end.

And a little technical information – the spruce wood cross beam roof, which has over 1,400 beams, is partly covered by triangular panels made of special ‘inflated plastic membrane’. Besides being extremely lightweight (100 times lighter than glass) it actually allows more sunlight through. However, some panels have been left empty to allow both natural light and rain to fall upon the garden.

And a little technical information – the spruce wood cross beam roof, which has over 1,400 beams, is partly covered by triangular panels made of special ‘inflated plastic membrane’. Besides being extremely lightweight (100 times lighter than glass) it actually allows more sunlight through. However, some panels have been left empty to allow both natural light and rain to fall upon the garden.