Updated: 6 June 2023 |

|

Length: About 3½ miles |

|

Duration: Around 3 hours |

|

Appendix: Click to view |

|

PDF: Click to download |

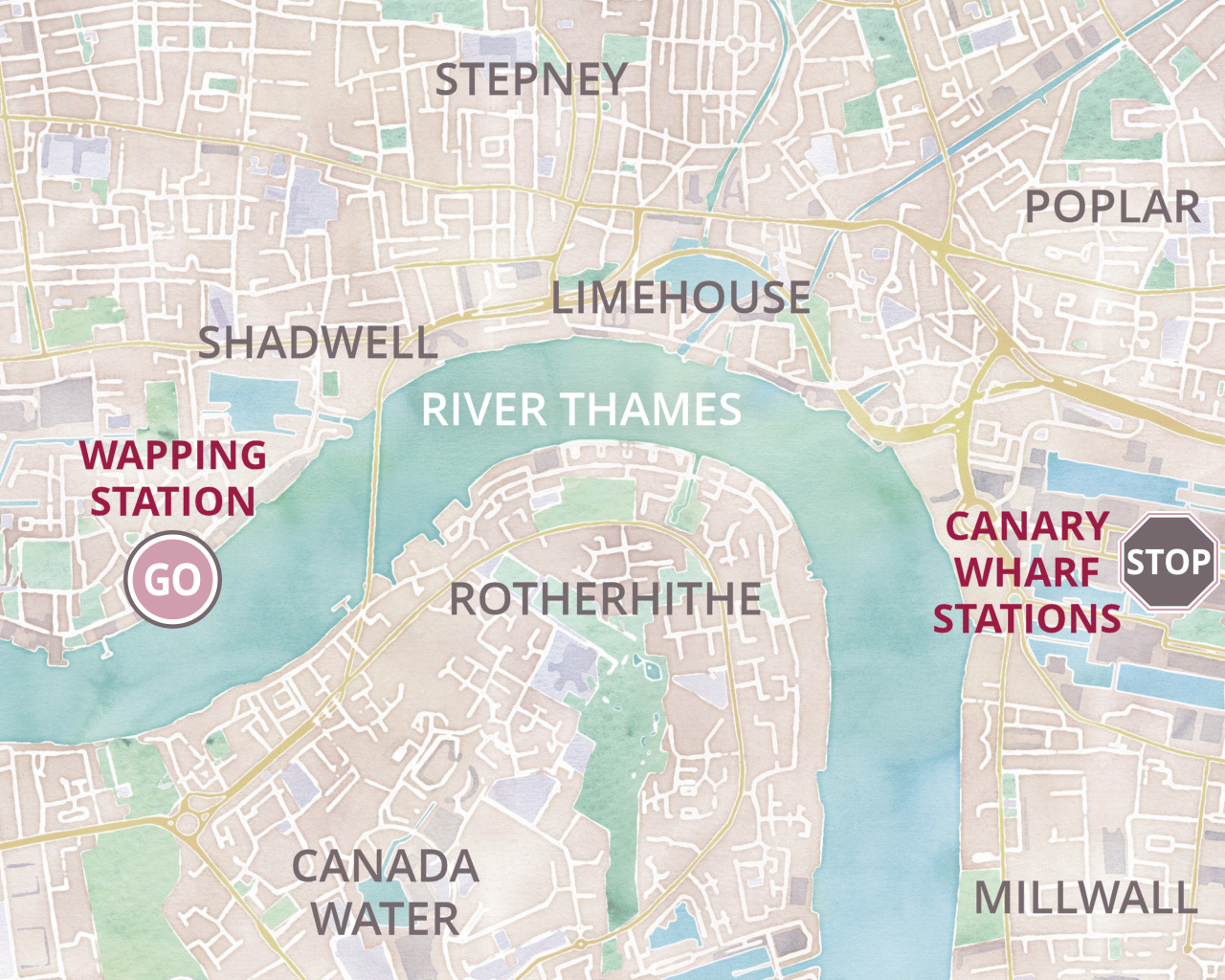

A walk from Wapping to Canary Wharf

NOTE

This walk can also be done as a continuation of the Tower Hill to Wapping walk, in which case you can pick up the walk from Tobacco Dock and continue down the ornamental canal to Shadwell Basin.

Start: Wapping station |

|

Finish: Canary Wharf stations |

GETTING HERE

The walk starts at Wapping station.

If you are travelling from central London, then you’ll probably find it easiest to take the Hammersmith & City line or the District line to Whitechapel – and change there on to a southbound Overground train. From there it’s just two stops to Wapping.

When you arrive at the station, turn left and follow the walk as below.

By bus

The only two bus routes that pass Wapping station are the 100 and the D3, neither of which will take you back to central London without changing.

However, for many people staying in central London the most convenient bus is likely to be the 100, which you can pick up at either St Paul’s (the stop is in King Edward Street) or Aldgate station or in Mansell Street, close to Tower Gateway station and just a couple of hundred yards from the Tower Hill tube station.

You then need to alight at Stop D in Wapping High Street. Walk up the street for a couple of hundred yards until you reach Brewhouse Lane – then pick up the walk from there.

For details of the Overground, Underground and buses, please consult the Transport for London website.

INTRODUCTION TO WAPPING

Originally Wapping was marshy land onto which the Thames would regularly overflow, but it was eventually drained. It had always been an isolated place but this was made worse when the docks were built as they were surrounded by very high walls to prevent theft. Huge numbers of people were moved out of their homes, ripping the heart out of the community and creating further deprivation. The area had always been very poor, and this remained the case even after the docks had been built as the dockers’ wages were at little more than subsistence levels and when work was short they could go for weeks without any money. Never being able to put anything aside meant hunger was sometimes a serious problem.

The area was badly hit by bombing during the Second World War, and many of the warehouses were damaged, some beyond repair. The result was that for many years the area became a very neglected and forgotten part of London. However, in the 1970s and 80s developers began to restore and renovate the damaged warehouses and build on the derelict bombsites, resulting in the many new apartment buildings that are here today, which have made the area a very popular place to live, attracting an eclectic mix of new residents.

STARTING THE WALK

Having turned left out of the station, continue straight ahead as the road becomes Wapping High Street, passing Wapping Dock Street and Wapping Lane on your right, and then the enormous King Henry’s Wharves and Gun Wharves on your left. They were so named because this was where Henry VIII built a foundry to make cannons for his navy. Although now converted into luxury apartments, the exterior of these huge warehouses appears to have retained their original facades.

Turn right into the narrow Brewhouse Lane (also known as Brewhouse Place) when you reach it. It runs up the side of the New Tower Building. For years there’s been a plot of waste ground on this corner, one of the few undeveloped sites in Wapping, but that’s about to change as permission to develop it has been granted. If for any reason the lane is closed to pedestrians, then retrace your footsteps back to Wapping Lane and walk up as far as Watts Street and pick up the walk again as below.

A point of interest – before you leave Wapping High Street and turn up Brewhouse Lane, ahead of you on the left you will be able to see the Captain Kidd pub and the original Metropolitan River Police Headquarters. Details of both are in the Tower Hill to Wapping walk.

As you walk up Brewhouse Lane notice the Tower Building, another very early apartment block built by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company in 1864.

The company was formed in 1863 by Sir Sidney Waterlow. He was a printer and philanthropist who later became a Lord Mayor of London. The company was a ‘model dwelling company’ – one of a group of private companies set up to improve the housing conditions of the working class by building homes specifically for them. They were not charities and had to ensure that investments in them received a competitive rate of interest. The homes they built were of a higher standard than would normally be built for working men and women, with better sanitation and less overcrowding. The Improved Industrial Dwellings Company was one of the largest and most successful of such enterprises and by 1900 housed 30,000 people.

![]()

Follow Brewhouse Lane around to the right. Chimney Court, the building facing you, is a good example of a 1990s conversion into apartments; it was originally a soap factory. The court’s name no doubt derives from the prominent smokestack located on Green Bank.

At the end of the road turn left into Wapping Lane, a street that’s at the heart of the Wapping community and still has shops such as a traditional butcher (a rare sight these days), a fishmonger, greengrocer, general grocery store, newsagent, pub – and even a Pizza Express restaurant.

Cross Green Bank then take the next left into Watts Street, alongside the little triangle of ‘green’. Notice on the left the carefully renovated blocks of flats (I love the large windows) built originally by an early housing association in co-operation with the local authority.

Directly ahead, on the corner of Meeting House Alley, is the Turner’s Old Star public house, (with the rather unusual view of the Shard beyond, which to me seems strangely out of place here.)

The artist J.M.W. Turner converted two cottages that he had inherited in 1830 into a tavern to be run by Sophia Booth, a widowed landlady from Margate, who was one of his mistresses. He spent much of his time here, particularly as he was fascinated by the River Thames, the source of many of his paintings. However, he tried to keep it a secret, no doubt partly because he was said to have had several other mistresses at the time, so rather than use his own name when he stayed here, he used a pseudonym of Sophia Booth’s name. As a result of his short height and ‘portly physique’ he was soon simply nicknamed ‘Puggy’. Amazingly, the pub is still going strong today, having been renovated in the 1980s.

Walk up Meeting House Alley, which runs up the right-hand side of the pub, then turn right into Chandler Street and then turn left back into Wapping Lane.

On the other side of the road is St Peter’s, the parish church of Wapping. The entrance is not obvious – it’s through an unusual arched entrance into a tiny courtyard. If the church is open, (it is most days) then it is worth going in to take a look. Whilst it might appear to be a Catholic church, it is actually Church of England, although run by the Society of Holy Cross, an Anglo-Catholic International Society.

Continue on up Wapping Lane for several minutes until you reach the bridge that crosses the Ornamental Canal – the same one you saw back in Hermitage Basin – and directly in front of you is the imposing brick-built Tobacco Dock.

In a dry dock between the ‘canal’ and Tobacco Dock are two sailing ships that are replicas named and designed after real ships. One was the 330-ton Three Sisters, which was built in the dockland’s Blackwall Yard in 1788 and used to sail to the East and West Indies to bring back tobacco and spices. The other was the Sea Lark, an American merchant schooner that was captured by the British navy in 1811. They were installed as part of the plan to create a major shopping and leisure complex here, which I explain shortly.

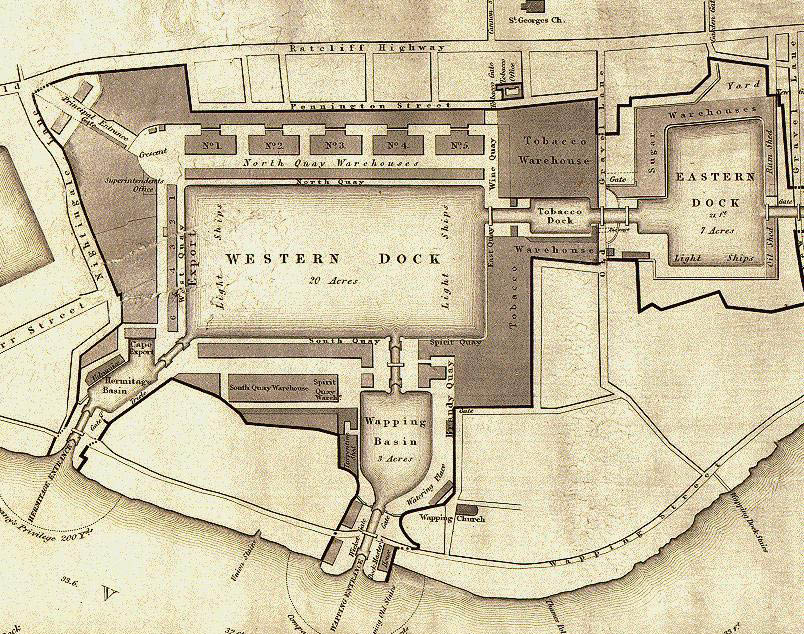

Tobacco Dock was designed by the London Docks’ architect Daniel Alexander and opened in 1814 as a safe and secure warehouse to store valuable cargoes, such as tobacco, wines and spirits, as well as furs and skins. To me it still looks more like a fortress than a conventional warehouse, which was probably how it was intended to look.

In the plan drawing shown below, Tobacco Dock is the large, almost-square building marked ‘Tobacco Warehouse’. Most of the docks have since been filled in.

At this point we leave Wapping Lane and follow the ornamental canal a little further east, towards Shadwell Basin.

To do so, go down the steps on the north side of the bridge (in front of Tobacco Dock – as though you were going to walk towards the sailing ships) but at the bottom turn left and walk under the bridge. (It is signposted ‘to Shadwell Basin’.) On your left you pass the Tobacco Dock car park whilst on the right is a large new apartment building.

After 150 yards or so the canal ends where a park (known as Wapping Woods) has been built over it but walk straight ahead through the park (veering slightly to the left) and after just another 100 yards or so the path picks up the canal again. And as a point of interest – if you then look at the wall on the left where the path drops down to the canal you can see the mooring posts of the canal’s original wall and appreciate just how wide it once was.

Pass under the iron bridge that would have once lifted to allow ships to pass through and you will then be standing at the west end of the Shadwell Basin.

Shadwell Basin has seen considerable housing development on the left side, but fortunately much of the rest has been left in a more natural state. At the far end was the lock where ships would have entered from the Thames, and we will be exploring around there shortly.

However, first turn right and walk along this ‘top end’ of the basin for 50 yards or so, towards the line of houses, and then go down the steep steps on the right. These take you down to Milk Yard – turn left and follow it to the right as it becomes Monza Street. This brings us into Wapping Wall.

Wapping Wall was so named because in 1536 an Act of Parliament, encouraged by Henry VIII, was passed that gave Cornelius Vanderdelf, (a Dutchman who had previously helped drain part of the Fens in Norfolk), permission to drain over 100 acres of marshland in the Wapping area, in return for which he was given half the land he managed to reclaim. A wall, extending from close to where Tower Bridge now is, to Shadwell in the east, was built to keep the river out of the newly drained land. However, after being breached on several occasions over the next few years, it was decided that the best way to strengthen and protect the wall was to build upon it and a number of houses were erected.

Wapping gradually became a damp, lonely and isolated settlement that was extremely poor. John Stow, the great chronicler of life in London in the 16th century, described the road through it as “a continual street or filthy passage with alleys and small tenements or cottages inhabited by sailors’ victuallers”.

At the end of Monza Street turn left along Wapping Wall – but first notice the Metropolitan Wharf on the other side of the street. It is a Grade II listed Victorian building that consists of five warehouses that were built between 1862 and 1868 and were used for storing coffee, cocoa, spices, oils, dried fruits, seeds, and coconut matting.

They were among the first warehouses in the area to be given a new lease of life, used initially, I understand, by artists. They’ve more recently been renovated into offices and studios, and a nice new restaurant (and café by day) has been created on the ground floor called Bottega Wharf. I love the spacious ground floor lobby area of the building – it has an original ‘warehouse feel’ to it and there’s also a riverside terrace at the rear, which at one time had public access, but that may have now changed. And if you’ve watched the television series called the Great British Sewing Bee then you will probably recognise the building, as this is where the 2014–15 shows were filmed.

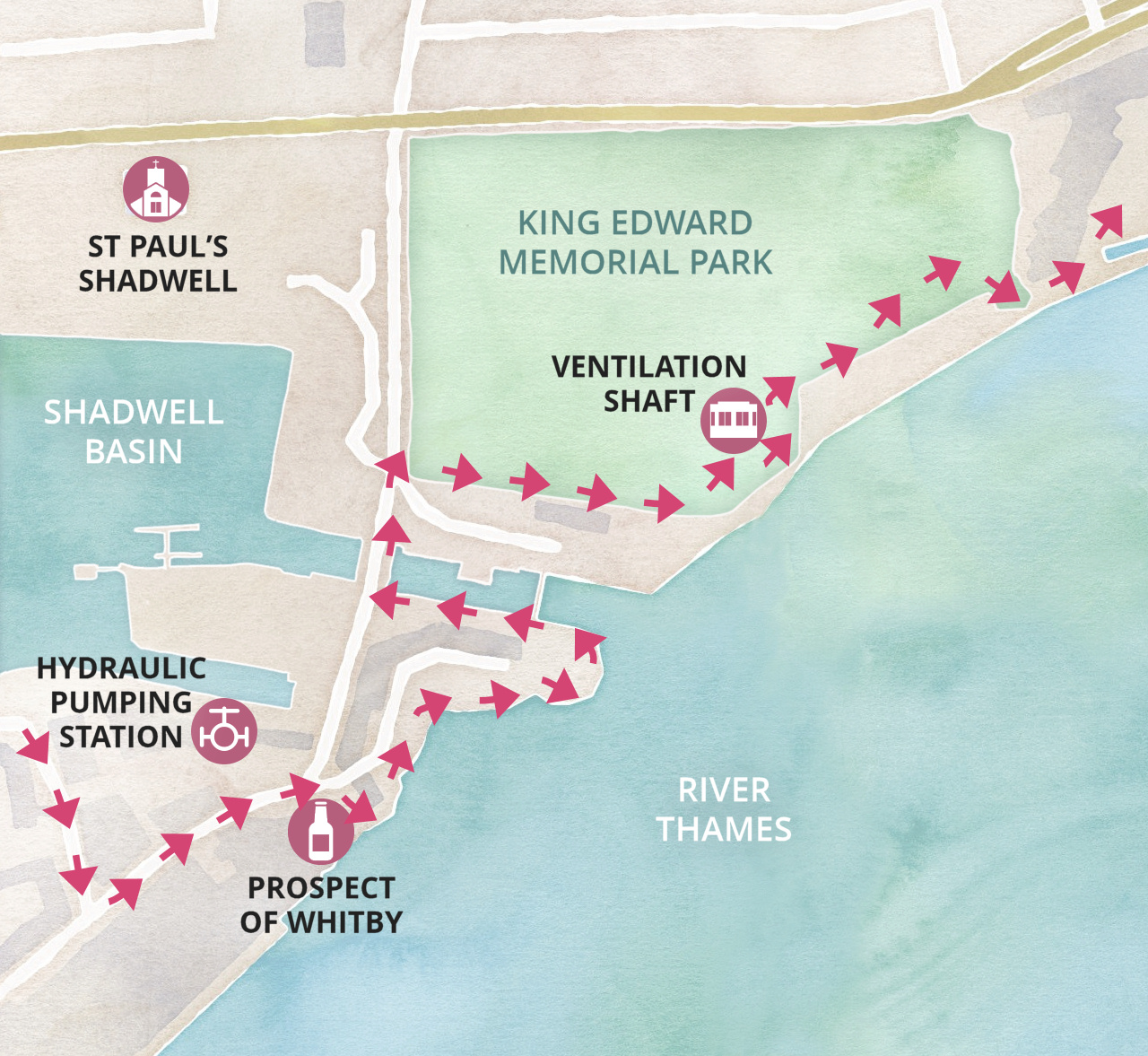

A hundred yards on is the famous Prospect of Whitby, but before you call in to take a look (it’s a must to do so!), walk down the side of the pub where you’ll find a set of stairs – these are the Pelican Stairs.

There are many such sets of ‘stairs’, as they’ve always been known, along the length of the Thames as it passes through London. They were built from the 14th century onwards to provide access to the river; with either non-existent or at best poorly maintained tracks, lanes or roads, many local people used the river to get about. Hundreds of ‘watermen’ would provide what were elementary water taxis or ferry services, picking up people from differing sets of stairs. In addition to that, as the Thames became busier and ships had to moor away from the quaysides and out in the river, getting a boat from Stairs such as these was the only way sailors could return to their ships after a (drunken) night ashore.

You can walk down these stairs at low tide; at the bottom is a small sandy beach but be very careful – the steps are very steep and nearly always very slippery. If you are able to go down, then notice the hangman’s noose at the rear of the pub.

The Prospect is said to be the oldest of London’s riverside pubs and dates back to 1520, when Henry VIII was on the throne. It was originally called the Pelican Inn, though most people called it the Devil’s Tavern because of some of the ‘wicked activities’ said to have taken place here; it was infamous for its bareknuckle fighting, cock fighting and other even less attractive activities. It was renamed the ‘Prospect of Whitby’, which was the name of a collier that used to sail down from the Yorkshire port of Whitby and moor alongside to unload coal for the hydraulic pumping station opposite.

Across the road from the Prospect, the large brick building behind big double gates and high walls was the Wapping Hydraulic Pumping Station. From the 1850s onwards, hydraulic power was used to operate swing bridges, lock-gates and cranes in the docks. Later they began providing the power to operate machines in factories, work the early lifts in places such as the Bank of England, posh shops in London’s West End and even the stage and curtains in the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane and the Royal Opera House. The pumping station and its history are fascinating, and I have put a few more details in the appendix.

Continuing our walk, directly ahead is a large and unusual looking ‘lift-bridge’, which we will cross shortly, but first turn right immediately after the Prospect of Whitby and walk through the access way of the Trafalgar Court apartment building. (It is open to the public, despite the confusing signs). The path takes you back to the river, where there are some excellent views – facing you across the Thames you can see a circular brick building, which is the south bank ventilation tower for the Thames Tunnel, more on which shortly. To the left of it, looking as though it’s on the other side of the river, but it’s because of a bend, are the towering buildings of Canary Wharf.

Carry on along this promenade and follow the path around and to the left – on your right you pass the entrance lock to the Shadwell Basin (you were standing at the far end earlier), the largest and most easterly entrance into the London Docks from the Thames.

By the end of the 19th century, ships had been getting larger and found it increasingly difficult to enter the docks at the original Wapping and Hermitage entrances that we saw earlier, so this larger entrance gave access to the Shadwell Basin that we saw earlier, and are about to see again.

The Basin is now the only part of the London Dock complex that hasn’t been filled in and built upon; instead it’s been preserved as a public recreational space and used for sailing and canoeing training, as well as fishing.

The housing complexes around the basin were built in the 1980s (supposedly in a style that reflects the warehouses in St Katharine’s Dock, which I personally fail to see) and it seems to have something of a ‘desolate’ feel to it at present, though I know there are plans to improve this.

The large steel Shadwell Bascule Bridge that gave access to the docks wasn’t actually built until the 1930s, and the hydraulic power to raise and lower it, together with the lock gates, came from the adjacent London Hydraulic Power Company.

Looking across the basin to the right you can see the spire of St Paul’s Church of Shadwell. It dates back to 1657 and is known as the ‘Church of Sea Captains’ as over seventy sea captains are buried in its graveyard. Previous church members have included Captain James Cook, who was baptised here, and the mother of US President Thomas Jefferson. Another claim to fame of St Paul’s Shadwell is that John Wesley preached here on a number of occasions and actually gave his last sermon in the church – he died less than a week later.

The original church fell into a very poor state of repair and was rebuilt in 1820, partly funded by a grant given by parliament to celebrate Wellington’s victory at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 (Wellington was a senior officer in the East India Company’s army, whose headquarters were close by.) Part of Shadwell Dock Basin was dug out of a large area of the church grounds.

Cross over the Shadwell Bridge and on the right you will see a sign for the Thames Path that runs down a lane alongside a sports ground which takes you into the King Edward Memorial Park. Don’t go through the first entrance that’s immediately alongside the lock, as it just leads into the Shadwell Basin Outdoor Activity Centre, but the one after it.

The park was established in 1922 to provide East Enders with much needed recreational space, as well as the opportunity of enjoying views of the Thames. Complete with a bandstand and park benches, it was a huge success.

Please note – currently large areas of the park are closed off, due to it being a major access point for tunnelling equipment for the Thames Tideway Tunnel. However, they have kept open the access through the park to continue a Thames walk. Whilst construction is underway, you will need to follow the possible diversion signs, but it’s best to remember that if there is a choice in paths, then always take the right hand one, which should be closest to the river.

The Tideway tunnel, otherwise known as London’s ‘Super Sewer’ is a huge project, rivalling in size the building of the Channel Tunnel and the Crossrail project.

Indeed, it will be nearly as long and wide as the Channel Tunnel and will cost over four billion pounds. When completed, which is estimated to be in 2023, it will carry millions of tons of raw sewage away from much of London to Beckton in the east, where it will be treated before being allowed to flow back into the River Thames. Here in King Edward Park is one of the principle tunnelling sites, and enormous 80ft shafts have been dug down to a depth of around 190ft, allowing giant tunnelling machines to bore this particular stage of the 23ft wide tunnel (sufficient to drive two London double-decker buses along, side by side).

More information on the Tideway Tunnel in the appendix.

Walk through the park but keeping to the path closest to the river – it leads out through a gate and you continue back along the riverside path. Pass a rather old wooden quay/jetty (despite my research, I still don’t know its history). However, it is now closed because of ‘health and safety’ concerns.

On the left are two enormous apartment blocks, part of a complex built on the site of Free Trade Wharf. Initially I thought they were unquestionably ugly, but each time I walk past I warm to them a little more. I have heard them referred to as the ‘Lego development’, because of their shape. They were built in the 1980s on the site of wharves that were originally owned by the East India Company, and though the site was purchased in 1977 by the Inner London Education Authority for a new London Polytechnic, it never happened, and the apartments were built here instead.

This was the site of a devastating fire in 1794 when many of the quayside warehouses were destroyed. It was the worst fire the docks had experienced between the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the German bombing raids in the Second World War. It was caused by an unattended kettle of pitch in a nearby barge builder’s yard boiling over. This then ignited a barge full of saltpetre, a major import in those days as it was used to make gunpowder as well as a meat preservative (hmmm). This set off a series of explosions that sent showers of burning saltpetre over a vast area.

The fire rapidly spread, consuming and destroying timber yards, ropeyards, numerous commercial buildings including inflammable sugar warehouses, ships as well as five hundred homes. To house the huge numbers of people made homeless, local churches erected over a hundred tents in nearby fields that were donated by the East India Company, Lloyds, the shipping insurer and the City of London Corporation. Some donations were even made by people who had simply come to see the devastation caused by the fire.

Next to the Free Trade Wharf is Atlantic Wharf and through a pair of iron gates set into one of the buildings you will see a couple of yards of railway track and a goods wagon, once used for taking goods from the wharf to the carts waiting to transport them along the Ratcliff Highway that runs behind and into London.

Another hundred yards or so further on is a little wooden bridge over another flight of ‘Thames Stairs’. Continue on along the ‘boulevard’ – it may look as though it is a ‘dead end’ as a block of apartments has been built out to the river’s edge, but keep going and follow it round – it may seem as though you are walking through the private rear terrace of the apartments – but it is a public right of way. The site was originally called Lendrum’s Wharf but later renamed Keepier Wharf because this was where the colliers from the Kepier mining area in County Durham unloaded coal.

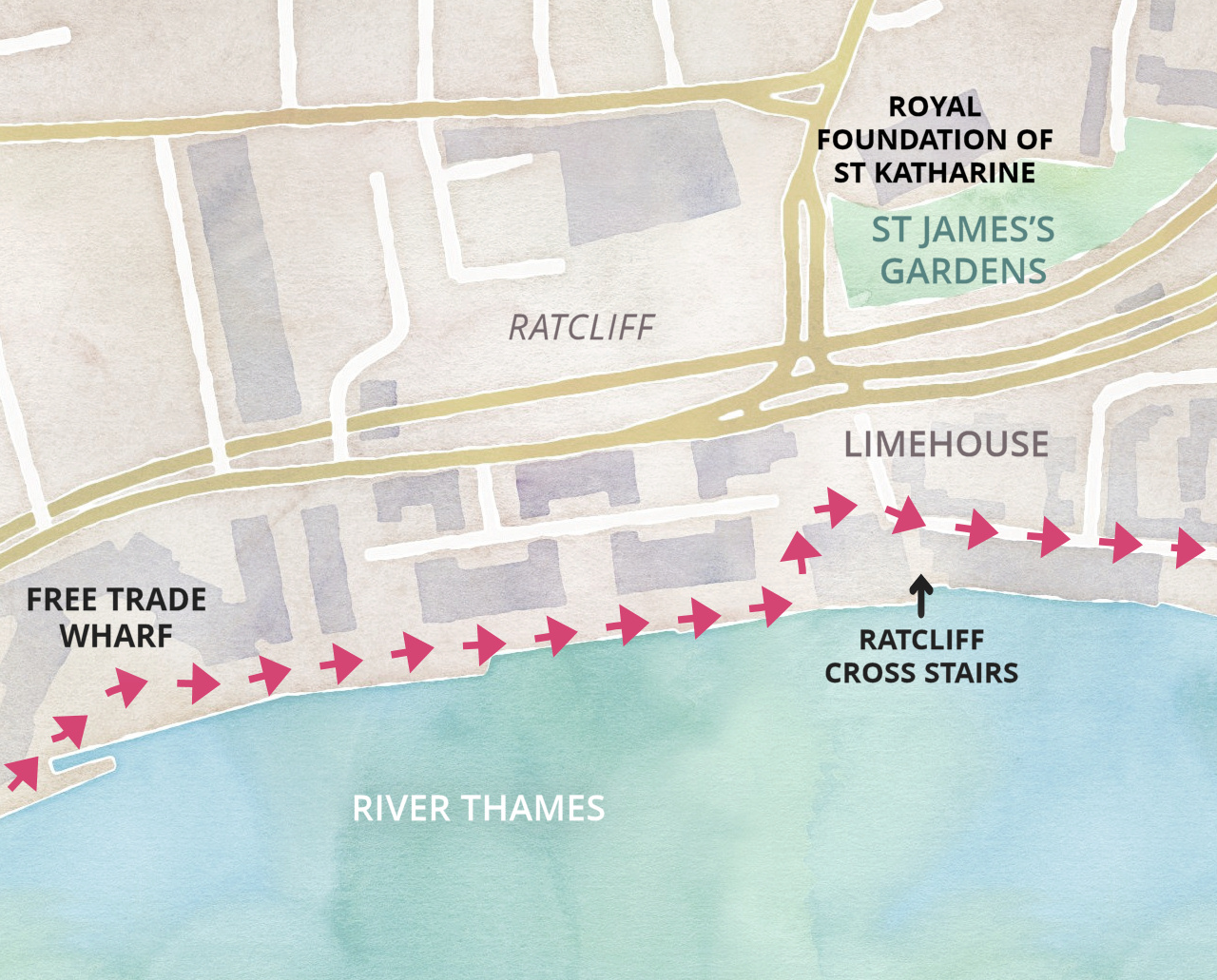

You are now at the start of Limehouse’s historic Narrow Street.

Running parallel to you on your left is The Highway – a depressing looking ‘expressway’ that carries an enormous amount of traffic out of London and through the Limehouse Link Tunnel into Canary Wharf and beyond towards Essex. Its name came about because originally it simply was a ‘high way’- a built up bank or causeway that allowed travellers to pass through even when the river was in flood. For many years it was known as the Ratcliff Highway and had a terrible reputation, partly due to the notorious ‘Ratcliff Murders’.

Walk straight ahead down Narrow Street, but before you do, take a look at the renowned Ratcliff Cross Stairs. They are adjacent to the Keepier Wharf building you have just walked around. There’s no sign – just a worn metal gate with blue railings, but if the tide is out it’s worth taking a look. It might not look much today, but this is a very historic and onetime very busy place. Many people have walked down these old stone steps – their last dry land for sometimes up to a year or even more. Some were setting off by sailing ship to explore, whilst others to start a new life in Australia, America or other ‘far off parts of the Empire’. Boatmen would pick up both the passengers and crew and row them out to their ships that would be moored close by.

Another warning though – as with all these old Thames stairs, be careful – the steps are always very slippery, even when they appear dry. At low tide there is a little sandy beach where you can get an unusual view of the river.

The first building in Narrow Street after the Ratcliff Cross Stairs is Phoenix Wharf (Number 14–16), a modern and plain apartment building, but next to it at No. 18 – 22 are the Ratcliff Wharf Apartments. These were built in the late 1950s on the site of bombed warehouses and unless you are an architect or builder, I doubt you’ll be interested to know that the one on the left was the first building in London to be constructed on piles rather than traditional foundations.

I do find it fascinating to discover the various uses that some of these wharves have had over the years – for example, at the end of the 19th century Phoenix Wharf was once a sail-maker’s; it then became a biscuit bakery and finally a tea chest maker. And I have to say at this point I am grateful for some of this information, which I couldn’t find anywhere else, that I found in a book called London’s Changing Riverscape – a collection of ‘then and now’ photographs and commentary. The book is still in print and well worth buying.

Commercial Wharf, at No. 24, the building with the ‘greenery’ on the outside, is original and I understand that for many years it housed the Corporation of Trinity House’s Ballast Office, where ship captains paid the toll for taking on board the ballast that was needed when sailing out of London without cargo. London imported considerably more than it exported and without the ballast, ships would be very unstable.

Look to the left up Spert Street – the unusual modern structure is the entrance to the Limehouse Link Tunnel that opened in 1993, part of the Docklands Regeneration Scheme to improve transport links with Canary Wharf.

The huge brick-built Sun Wharf at No. 28 is another original building – still with the hoists and hauling way doors on each floor.

Time to stop for a meal?

La Figa is open from noon until 3pm and from 6pm until 11pm. From personal experience they do excellent Italian dishes at realistic prices, with friendly and cheerful service. They will serve coffees, etc. as well.

Time to stop for a meal?

La Figa is open from noon until 3pm and from 6pm until 11pm. From personal experience they do excellent Italian dishes at realistic prices, with friendly and cheerful service. They will serve coffees, etc. as well.

Follow the Thames Path sign* and turn to the right, between Sun Wharf and Old Sun Wharf – (why is it called that when it is obviously a more modern development?). This was at one time the home of film director David Lean, famous for classic films such as Brief Encounter and Bridge over the River Kwai, who was one of the earliest people to recognise the attraction of living in Limehouse, long before it became trendy.

* Note – before you turn down the path, on the opposite side of the road is Mosaic Square. Here you will find La Figa Italian restaurant (noticeable by the pedestrian ramp leading up to it as well as steps).

Once you are alongside the Thames, look across the river and you can now see just how close you are to Canary Wharf.

As you approach the end of the short path you pass a semi-circular building that was originally the Dockmaster’s House. It’s situated alongside the entrance lock into the Limehouse Basin, but after the lock and basin were closed to commercial traffic it became a pub and is now a Gordon Ramsay restaurant called ‘The Narrow’. Its rounded shape and large windows mean the restaurant has excellent views of the river.

Follow the path around the restaurant and up the steps to rejoin Narrow Street. Turn right, cross over the road and turn left walk down the right-hand side of the lock – the signpost helpfully tells you that it’s just a 28 mile walk to Hertford, where the Limehouse Cut / River Lee Navigation terminates. But that’s not for today.

I’ll just mention here that if you cross the bridge and turn to the right through the gate that leads back to the river (it is a public access way, despite what the sign may indicate) and walk for 50 yards or so, you come to what was the original entrance into the Limehouse Basin. It was built in 1770, but as you can probably appreciate it became too narrow for larger boats to access the basin and closed in 1968. Incidentally the house on the corner of the inlet (Number 48 Narrow Street) was a pub until 1914, and owned by a formidable woman known as ‘Tug Boat Tessie’. Besides being a landlady she owned her own fleet of boats, and it was hardly surprising that she had quite some reputation.

The Limehouse Basin (originally called the Regent’s Canal Dock) is the starting point for both the Regent’s Canal and the Limehouse Cut. The former provided a link for boats to travel between the Thames and the rest of Britain’s canal network via the Grand Union Canal branch at Little Venice, just quarter of a mile from Paddington station in London. The Limehouse Cut links the Thames with the River Lea, which runs from Hertfordshire down the eastern side of London and joins the Thames at a place called Trinity Buoy Wharf, almost opposite the O2.

Limehouse Basin was once a very busy place – in just 1865 alone around 1,500 ships and over 15,000 barges are said to have used it. This success resulted in it being enlarged several times. As ships grew bigger, the original lock entrance that I’ve just mentioned became too small and the present larger ‘ship lock’ where you stand today was built. The basin finally closed to commercial traffic in 1969 and became a marina in 2001.

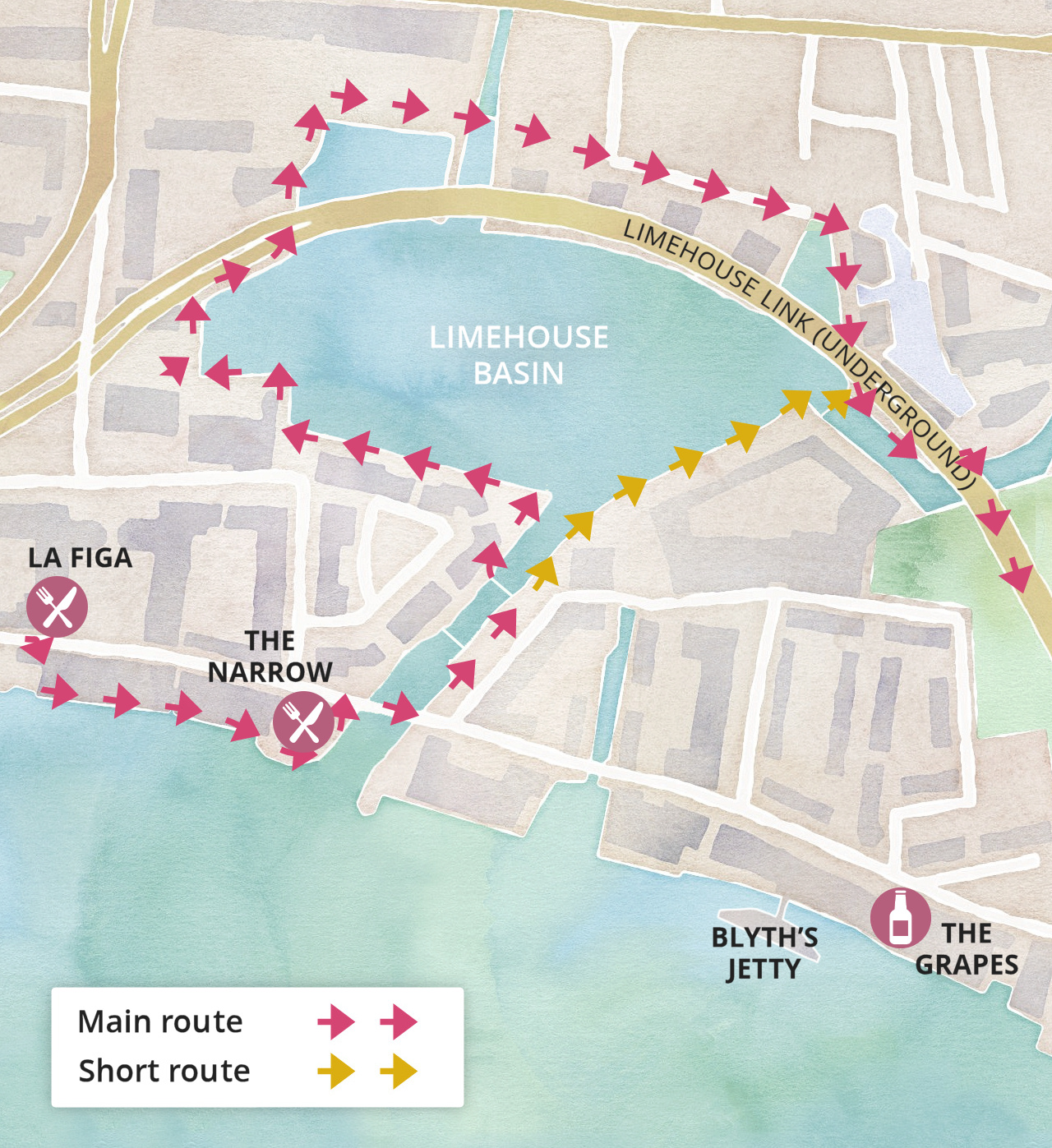

Carry on walking alongside the lock – and here you have two options. One is to simply walk along the right-hand side of the basin, whilst the other is to walk around the basin in a clockwise direction. If you have the time and energy then you do see a little more on the latter and it only takes an additional ten minutes.

The shorter route

Walk past the lock and follow the path around to the right. Cut into the wall by the second set of iron steps on your right, you might be able to make out the inscription that says, “This stone was set 20th June 1899 by James Staats, Chairman” – though chairman of what it doesn’t say. However, I discovered he was an engineer and director of many railway companies as well as the Regent’s Canal. (Although the Regent’s Canal starts just across the basin from where you are now, it’s difficult to make out from here.)

At the end of the walkway go up the steps – the sign says ‘Limehouse Cut’ – cross over it via the pedestrian bridge and here the walk continues to the right. This is where the slightly longer ‘option 2’ walk around the basin joins, so please pick it up again after that.

For the second option that goes around the basin, cross the bridge over the lock and walk to the right. The route is self-explanatory – you more or less keep to the edge of the basin – so pass the Dockmaster’s/Marina office then turn right at the estate agent’s office.

On the other side of the basin you walk alongside the viaduct that carries the DLR trains (Docklands Light Railway), from Bank and Tower Gateway stations to Canary Wharf, Greenwich, Stratford, etc. However, it was built to carry one of the earliest railways in London – the London and Blackwall Railway (and I’ve put more information in the appendix).

Cross over the little bridge – this is the start of the Regent’s Canal and the lock is the canal’s official ‘Number 1 Lock’ – called the Commercial Road Lock – and the first of twelve on the 8½ mile length of the canal from here to Paddington. It has a tow path for most of its length and passes through Mile End, King’s Cross, Camden, Regent’s Park, Little Venice and then Paddington. (The section from Paddington to Camden Market is particularly interesting and it is covered in a separate walk.)

I have put more information about the Regent’s Canal in the appendix.

Walk up the steps, still keeping the viaduct on your left – notice the white mooring bollards that show how much wider the basin was before the apartments were built.

Notice also the unusual brick-built hexagonal tower and chimney on the other side of the viaduct. This is the Limehouse Dock Tower that was built in the 1860s to provide the hydraulic power to operate the original ‘ship lock’.

The process involved a steam engine pumping water up into a huge tank on the top of the tower, which was called an accumulator. It needed quite some force to do this, because on top of the tank was a 100-ton weight. When a lock gate or swing bridge needed opening, or a crane operated, then it was this extremely high-pressure water that would operate it. Some of the building was damaged in the Second World War and has since been demolished, but what remains has been preserved and listed, and this includes the boiler’s chimney and the ‘accumulator tower’. A spiral staircase now goes up through the ‘weight case and chimney’ to a viewing platform on the roof which opens on selected days of the year.

Following the path around to the right, passing the Limehouse Gallery and a dental practice and within 50 yards or so, you reach the top of a flight of steps leading back down to the basin. This is where we join the shorter walk.

Continue straight ahead, alongside the Limehouse Cut and after 50 yards or so, cross back over the canal at the next bridge and continue straight ahead. A sign says, ‘historic pubs’ – however, it’s a bit behind the times as unfortunately there is now only one.

You are now in a park called Ropemakers Fields, so named as this was the site of the George Magget’s Ropeworks, and the ropes would have been laid out here to be twisted whilst being made.

Ahead is a small bandstand that was built using columns reclaimed from a 19th century St Katharine’s Docks warehouse and here we take the path to the right into a little street also called Ropemakers Fields. The first house on your right (Number 27) used to be a pub called ‘The House They Left Behind’ and until recently you could see where the old pub sign once hung, but all references to it have now been removed. And the reason for the unusual name? A light-hearted reference to the fact that all the other houses in the street were damaged or destroyed by bombing in the Second World War and later demolished, leaving just the pub still standing.

Just a little further down on the same side there used to be a brewery owned by Taylor Walker, whose speciality from 1830 onwards was the brewing of Pale India Ale. This used to be exported to satisfy the needs of Londoners living and working in Australia and India. Although badly damaged in the war, it continued brewing until 1960 when it finally closed down and houses built on the site.

This short street takes you back into Narrow Street. On the corner is a statue of a herring gull standing on a pile of coiled rope. It was created in 1994 by sculptor Jane Ackroyd, who specialises in working with metal.

You are now back on Narrow Street and facing you on the other side is a particularly splendid row of Georgian terraced houses. Many houses and buildings along the street were either badly damaged or destroyed in the Second World War, but fortunately these were left standing. However, with the exception of the Grapes, this was left abandoned for many years, but writer and film maker Andrew Sinclair bought and set about renovating and preserving one of them, and then persuaded friends to do the same.

The Grapes, on the end of the terrace, is definitely one of my favourite London pubs. As probably befits a pub in Narrow Street, it’s very narrow! And very old – over five hundred years in fact. Even if you don’t fancy a drink you must at least put your head around the door and take a look. There are a few seats and tables just inside the entrance, and several more at the back, with the bar in between, whilst an equally small terrace at the back overlooks the river. It’s one of the few old pubs that hasn’t been modernised and still has a lovely ‘olde-worlde’ feel about it. It serves a good selection of real ales and bar meals and, up a very narrow steep staircase, is a small restaurant with just six tables.

From the terrace you can see a carved figure of a man standing on top of a wooden pillar in the river; and if you can’t make out who it looks like then I’ll help … it’s of Sir Ian McKellen, carved by the award-winning sculptor Antony Gormley who is a friend of Ian’s. Amongst many famous pieces of art Gormley has created is the ‘Angel of the North’.

(If there’s no room on the terrace, then I explain shortly another way of viewing the rear of the pub and the river.)

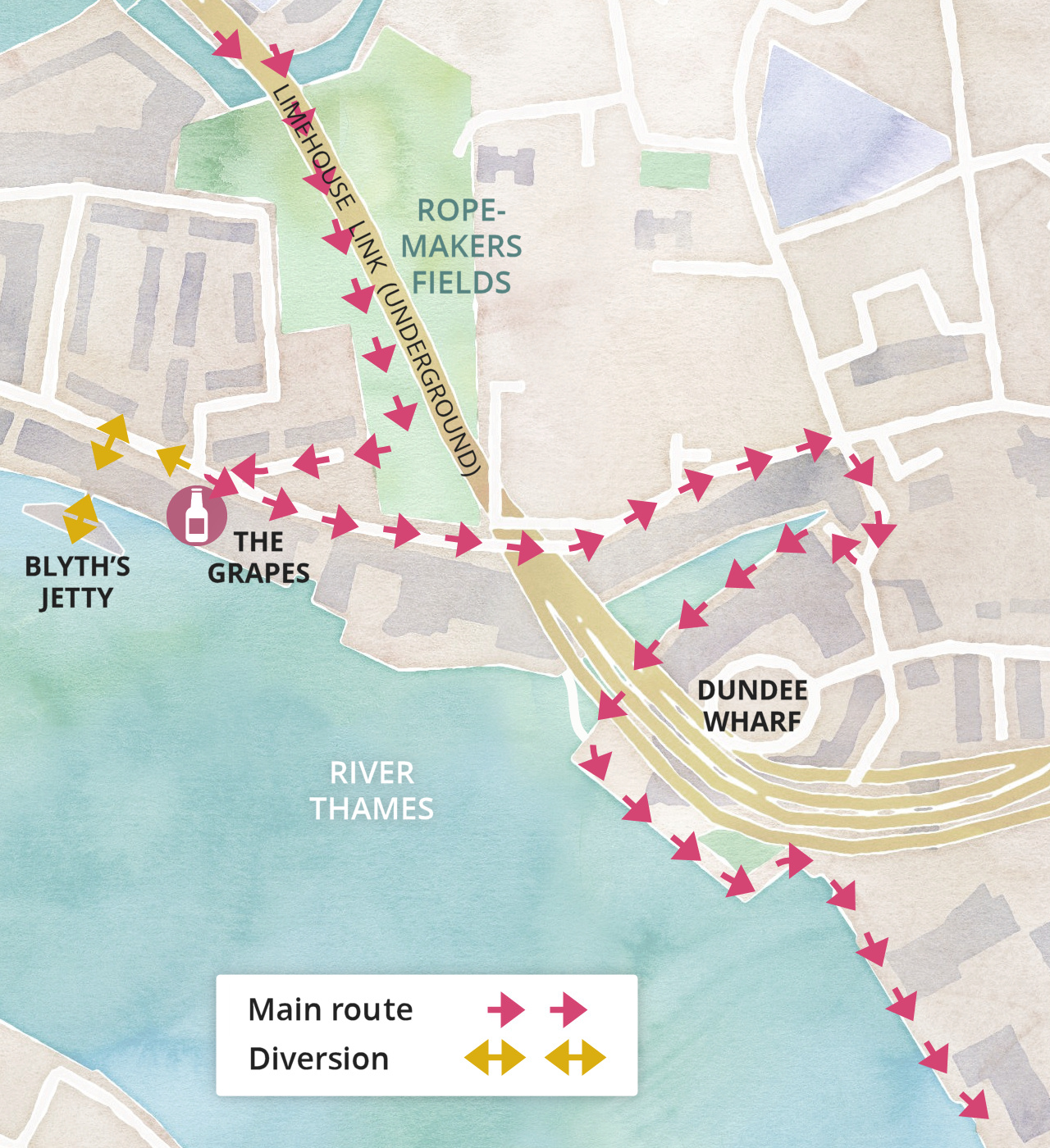

Diversion: Blyth’s Jetty |

Optional 50 yards’ diversion (but it may no longer be viable)

On leaving the Grapes continue to walk to back up Narrow Street – or if you are outside facing the Grapes then turn right – walk past the modern Blyth’s Wharf apartment building on your left and you will see a sign saying ‘Access to jetty’. The gate might look locked, but it isn’t; simply lift the drop handle. [A reader has kindly let me know that, as of June 2023, the gate was padlocked and this appeared to him to be a permanent arrangement.] The next gate will be closed but set in the wall is the button to open it. You then step out onto a wooden jetty and have more fabulous views up and down the river – and a good view of the river frontage of the Grapes pub and the statue of Ian McKellen. (I’m not sure how the people who have presumably paid huge amounts of money to live in these trendy riverside apartments feel about people being able to peer into their windows.) The little wharf was built in the early 1900s to enable colliers to unload their freight for a power station that used to be along Narrow Street. It’s since been demolished, with apartments built in its place.

I think it is nice to pause here and ponder on the fact that this was another place where early explorers set off to discover far off lands, often not returning for many years – if ever of course. And just on a tiny wooden sailing ship with hardly any navigation aids, limited food and water … but presumably just lots of optimism!

Leave the jetty and turn right back down Narrow Street, passing the Grapes and the row of early Georgian houses – (I’ve discovered you can tell they are ‘early’ Georgian because the windows are flush with the front of the house, whereas in late Georgian houses they are recessed).

At Number 92 there was once another illustrious old pub – Booty’s Riverside Bar, which finally closed in 2012 and the house has since been restored. Booty’s was originally called the Waterman’s Arms and for a long time was run by a legendary East End character known as Tugboat Annie. Her real name was Annie Fisher, and she ran a fleet of over twenty Thames barges. She must have been one hell of a tough character to be doing this in what then was even more of a “man’s world”.

Next is the Duke Shore Wharf – follow the Thames Path sign (opposite the main entrance into Ropemakers Fields Park), through a gated ‘archway’ back to the Thames Path.

(This is currently closed for building works, so if that’s still the case then simply continue ahead and pick up the walk further down.)

However, if it is open then from the rear you can see back up to the wooden jetty at the rear of the Grapes pub. Looking further back up the Thames are the skyscrapers of the City; the Gherkin in the foreground and just to the left the Cheesegrater and Walkie Talkie buildings, whilst higher than them all is the Shard. On the other side of the river you can see the well-preserved Columbia Wharf.

You are now on what was once the extensive Dunbar Wharf, owned by Duncan Dunbar & Sons, who ran a fleet of fast sailing ships that operated to Australia, India and the Americas. The first voluntary (i.e. not convict) emigrants to Australia sailed from here.

Pass through the next gate (again unlocked during daylight hours) and you come to one of the oldest and best preserved parts of the district – Limehouse Wharf, which we see again shortly when I give more information about it.

Don’t cross the bridge, but instead turn left and follow the path under the arch and back onto Narrow Street then turn right.

- If access to the Thames Path I mentioned above is still closed when you do the walk, continue on down Narrow Street and pick up the walk again here.

This is a fascinating short stretch as many of the frontages of the early 19th century warehouses along here have been well preserved. Some have been rebuilt in a more modern style, though others – like my favourite, the ‘Sailmakers House’ at Number 136 – still look like the warehouse it once was. (And notice the number of the ‘house’ next door – 136½.)

An elderly resident who I once chatted with told me that the original Gordon’s gin distillery was based here but I can’t find any reference to that – everything I have read about Gordon’s talks about its original distillery being in Clerkenwell. However, I have a feeling the story may have more to do with the fact that juniper berries were once stored at the adjacent St Dunstan’s Wharf – juniper is of course used to make the famous London gin.

I asked about the doors of the buildings here all being painted green, and whether correct or not I was told that this was a planning requirement. Apparently, the particular shade of green should be ‘Buckingham Green’ – but it would appear that this isn’t strictly enforced.

A couple of doors down, at Number 148, is another favourite of mine – the lovely old brick building with the ‘hauling doors’ on first and second floors and a sign on it saying, ‘J & R Wilson’. We see the waterside of it shortly, where a sign on it says ‘Ship Stores Merchants’. I looked it up in a 1921 street index and it was still that then.

We will turn right down Three Colt Street (here Narrow Street becomes the Limehouse Causeway), but before you do, look to the left and you can see the lovely St Anne’s Church, the parish church of Limehouse.

St Anne’s Church was built in 1725 by Nicholas Hawksmoor (who also built several others in the area). Queen Anne, the monarch at the time, said that as it was so close to the river it would be a good place for ships’ captains to register important events that were taking place at sea. As a result, it was given the right to display the White Ensign at all times (the second most senior ensign of the Royal Navy, which can normally only be flown at special times). It is still flown on the church tower and the maritime connection continues to exist as its current rector is honorary Chaplain to the Royal Navy. And notice the church clock – it was designed to be seen by ships on the river and as a result is one of the highest in Britain. The face of its clock is particularly large and clear in order for it to be seen by ships on the river and it was made by the company who built the clock faces for Big Ben.

Although the church is not strictly a part of the walk, it is very interesting, so I have put more information in the appendix.

We turn right now down Three Colt Street and in fifty yards or so, just after the bend and the Poplar Children’s Centre, on the right-hand side you’ll see a double-gated entrance into what appears to be a private courtyard between the buildings. However, it is not private and to the left of the double gates is a smaller gate with a keypad – press the button marked ‘Trades’ to enter. (There’s a sign beside the gate that explains this is the correct way to enter.)

Walk through and you find yourself on the other side of the Limekiln Dock and the rear of the row of converted warehouses you passed just now. The one we saw the front of just now, ‘J & R Wilson & Co (London) Ltd, ship stores’ – has been particularly well restored, as was its frontage.

Boats would sail in from the Thames and unload their cargo straight into the rear of the warehouses. And if you wonder whether the inlet floods, then just look at the height of the water marks on the wall opposite! When there is a high tide – especially one of the monthly ‘spring tides’ linked to a strong easterly wind blowing up the Thames, then it can become a problem.

According to old maps, a stream that rose in Stepney in London’s East End flowed into the Thames here. Like most of London’s small rivers that did this, over the years it became an ‘open sewer’ and this one was known locally as the Black Ditch. Then in the mid-18th century, this was the site of limekilns and Britain’s first soft paste porcelain factory – hence the name ‘Limehouse’.

Follow the path around the side of the dock – there’s another gate and you just need to press the green button on the left of it and pull the gate towards you to pass through.

Continue around to the left, passing under the ‘legs’ of the unusual apartment building whose iron gantries and walkways provide residents with access to its terraces. Built in 1997 on the site of the Dundee Wharf, the unusual design gives it a sort of ‘dockside feel’. Having said that, it also reminds me of something out of HG Wells’ novel ‘War of the Worlds’.

Dundee Wharf used to be owned by the Dundee, Perth and London Shipping Company. I have an old photograph that shows an enormous warehouse on the site with a sign saying, ‘Dundee Wharf – Dundee, Perth & London Shipping Company – Steamers Twice Weekly’. The company owned a number of wharves all along here called the Dundee; Aberdeen; Caledonia; and Dunbar Wharves – and in the 1800s they had two paddle steamers – the SS London and SS Perth – which operated a twice-weekly service carrying passengers and freight from here to Dundee and Edinburgh’s Leith Docks. Apparently, the last ship to use Dundee Wharf on a regular basis was the Lockett Wilson, which ran a service to Paris via the River Seine.

Follow the broad riverside path around to the left that becomes more of a promenade as it gets closer to Canary Wharf. Wharves and warehouses ran all the way along this stretch – one was for unloading and storing bananas, whilst next to that was the ‘River Plate Wharf’, the departure point for ships to South America. Some of these wharves were upgraded in the 1930s, but then badly damaged during the Second World War and although partly rebuilt afterwards, most had finally closed by the late 1960s. One of the last that we pass – and there is a stone plaque to commemorate it – is the site of Aberdeen Wharf. This was once used for shipbuilding and then from the 1820s until 1948 was the base for the Aberdeen and London Steam Navigation Company’s regular weekly or twice weekly services to Aberdeen. It carried livestock for the London markets and general cargo whilst in the summer months, passengers travelling to and from Scotland.

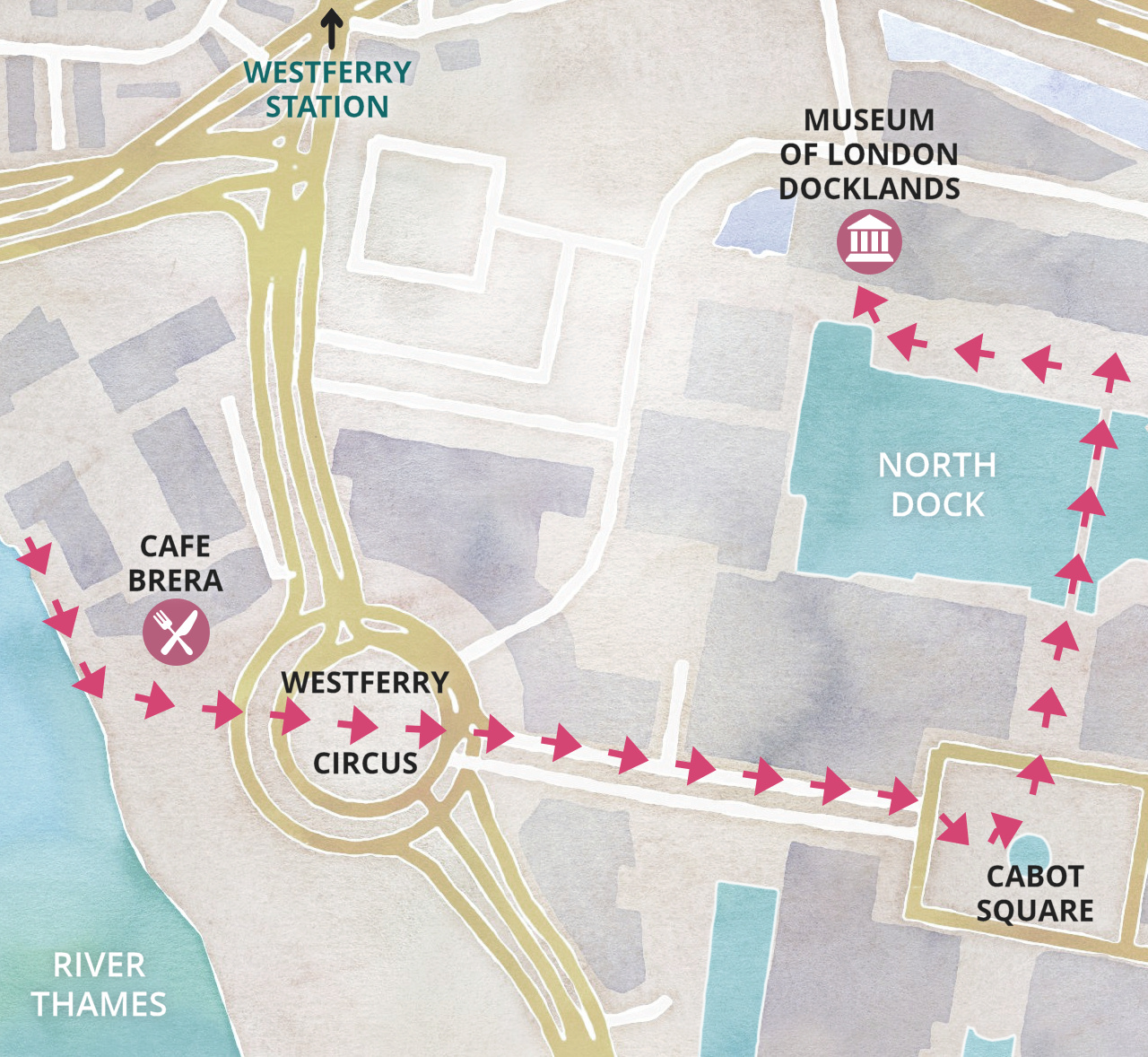

You will shortly see a path on the left with a sign saying Westferry DLR station. If you are prepared to miss Canary Wharf then you can catch a DLR train from there back to central London.

Looking further down river you can see the more recent developments along the west side of the Isle of Dogs (this will be the basis of a separate walk that starts at Canary Wharf and takes you right around the ‘island’).

On your left is the Four Seasons Hotel, with restaurants and a gym on the ground floor, whilst on your right is the Canary Wharf Thames Clipper Pier. If you haven’t used the Clipper service before and you are heading back to London after the walk, then it’s a great way to return. Stops include the Tower of London, London Bridge, Blackfriars, Embankment and Westminster. They accept Oyster cards as well as credit cards and cash. (There’s also a shuttle service that operates just across the river to the Doubletree Hilton Hotel opposite.)

Ahead of you is a wide flight of steps, which we climb to reach Canary Wharf – but notice first the ultra-thin 130-ft high carbon fibre sculpture called ‘Windward’, which despite its height is not spotted by most people.

To the right of the steps are four excellent (but rather pricey) restaurants, however if you are in need of a drink or sandwich then on the left at the top of the steps is the Cafe Brera, and with outside seating it is a lovely spot to enjoy a coffee whilst looking back over the river. (Across on the other side of the river is Columbus Wharf and the Doubletree Hilton Docklands Hotel.)

To reach the centre of Canary Wharf, climb the wide flight of steps that lead up to Westferry Circus. (If you’re feeling a little weary by now, then there’s a lift in the right-hand corner.)

At the top of the steps, cross the road and walk straight ahead through the attractive circular gardens (there are nice toilets on the left-hand side) and carry on into West India Avenue.

And I’ll just mention here that as you look ahead and see the various skyscrapers, still the tallest of them all is the 770-ft high, 50-storey One Canada Square. It was built as the centrepiece for the new Canary Wharf development that actually opened as far back as 1991. The architect Cesar Pelli chose the particularly striking stainless-steel cladding as he wanted a material that could be seen through the London mists and fogs. The building cost £624 million.

If you are planning on heading back into central London by bus, there are stops are on the right-hand side of West India Avenue. There are also other stops to pick up these same buses further ahead.

Continue on down the left-hand side of West India Avenue and when you reach Cabot Square walk across and up into it.

You can’t miss the fountain in the centre. This can be quite a windy spot, so to avoid people getting soaked when it’s gusty the height of the water is controlled by a tiny wind monitor – or to use the correct term, an anemometer – which you can see on the top of one of the high lampposts in the road alongside.

The cast lead semi-circle crystal glass panels in each corner of the square are rather attractive. They form the cladding for the four ventilation shafts for the car park below and turn different shades of light and colour.

Leave the square on the left-hand side, cross over the road and walk through the wide gap between the buildings – it’s called Wren Landing – and walk down the wide steps.

Further steps take you down to the North Dock bridge, (actually constructed on pontoons), that leads across the West India Dock.

The buildings on the other side – you’ll see a sign on them saying ‘Port East’ – are the dock’s original warehouses and at one time stored sugar, rum and other imports from the West Indies. They have been refurbished but without losing much of the original features. The ground floors of most of these have mostly been converted into bars and restaurants, with large terraces for al fresco drinking and dining in front. The exception is a building on the left side which is the home of the Museum of London Docklands, which is well worth a visit, perhaps on another occasion when you have more time.

You have two options here – depending on how much time and energy you have.

If you are now ready to return to central London, then follow the details below.

However, if you would like to see more, then move on to the section entitled ‘Seeing more of Canary Wharf’.

Finish: Here, optionally |

HEADING BACK TO CENTRAL LONDON

By bus

If you are planning on going back to central London by bus, then the relevant bus stops are on the opposite side of West India Avenue, where you walked along just now.

The bus services include –

- 135 to Old Street via Liverpool Street

- 277 to Dalston via Victoria Park and Hackney

- D3 to Bethnal Green via Wapping

- D7 to Mile End

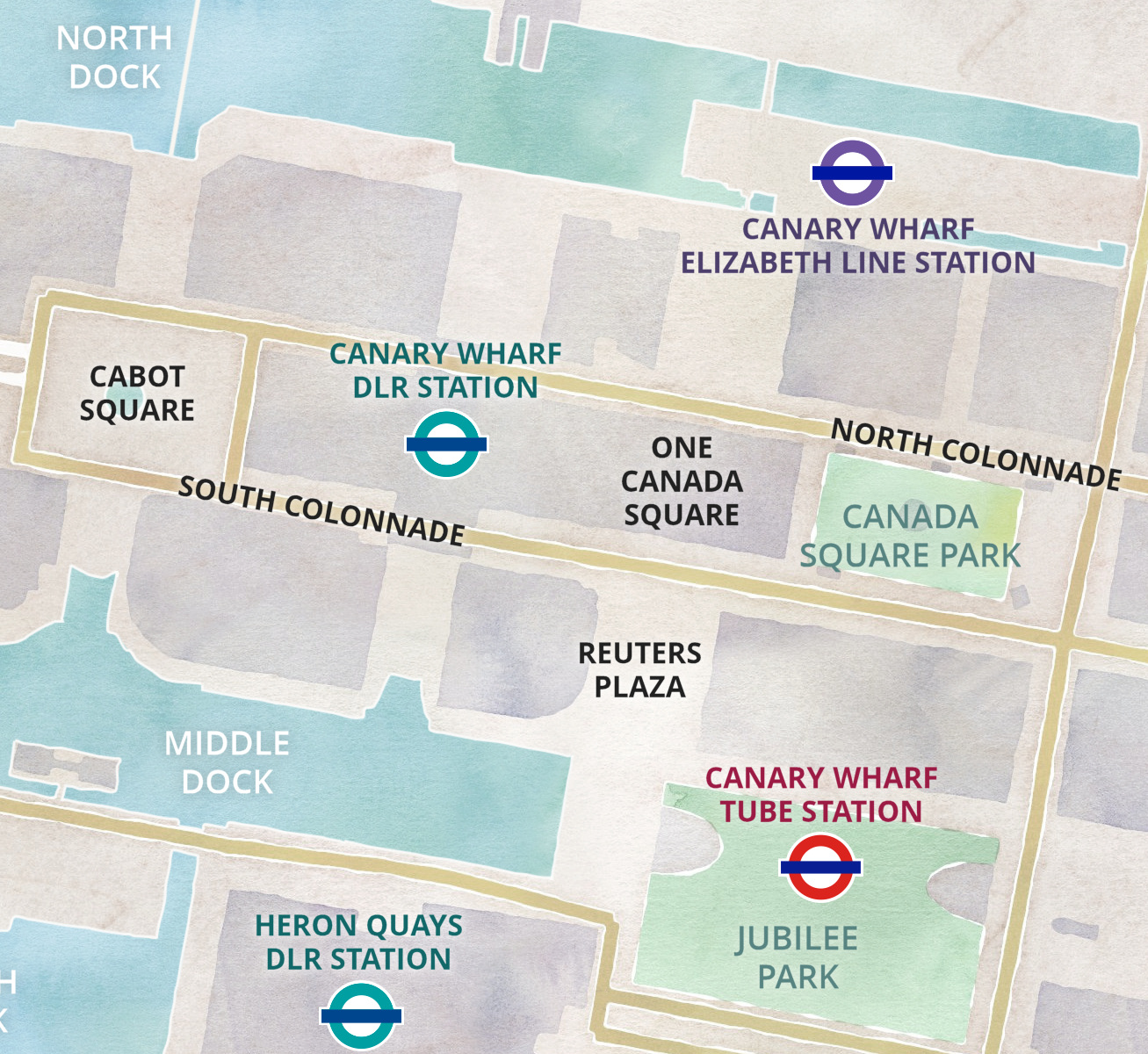

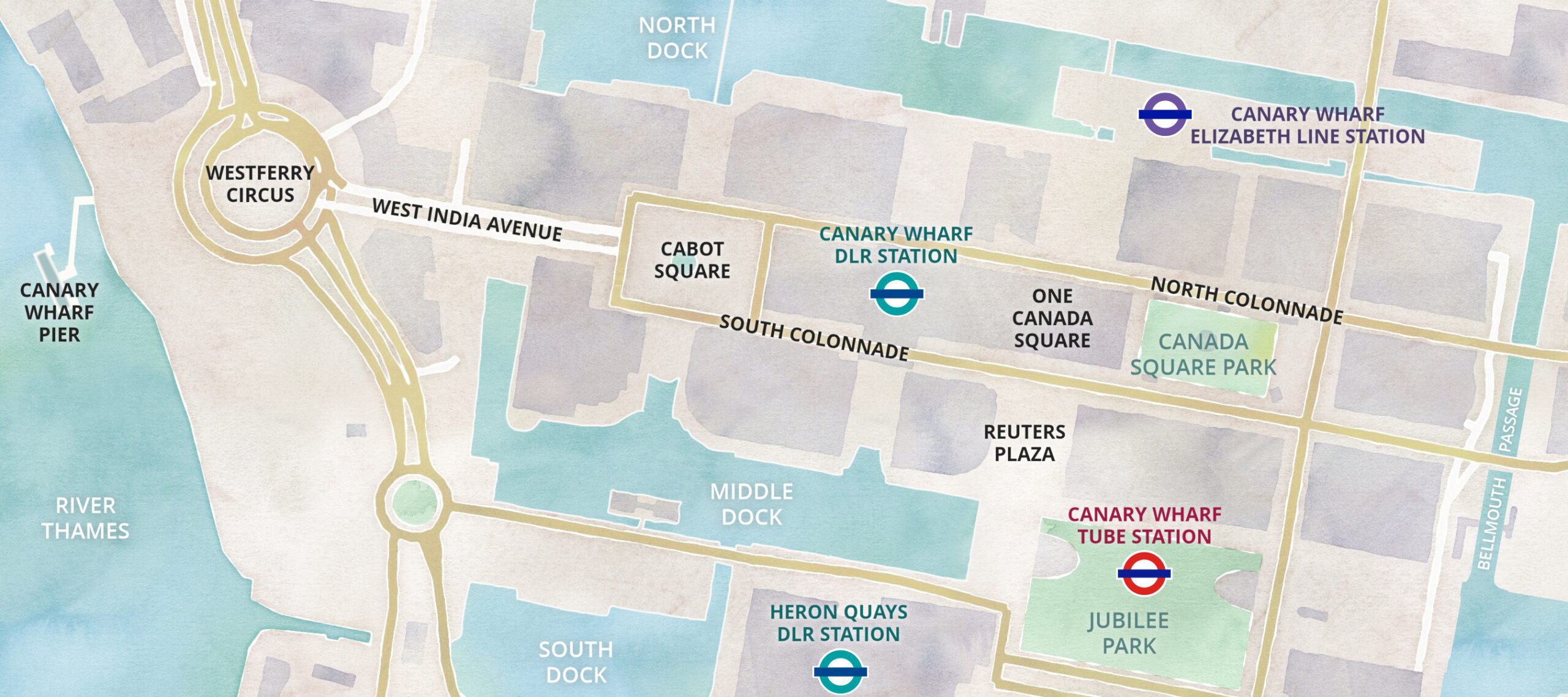

By the DLR or Jubilee line or Elizabeth line

To make your way now to either the DLR station or the tube station then walk back up to fountain in the square and turn left – go down the steps and cross over into the clearly marked entrance to Cabot Place.

Walk to the left of the escalator – and you are in the concourse beneath the DLR station and take the escalator up to whichever platform you require. (Platforms 4 & 5 are for trains to Bank or Tower Gateway – for the latter you need to change at Shadwell.)

However, for the Canary Wharf Jubilee line station – continue straight ahead from this concourse until you come to the circular atrium/plaza with shops around the sides and escalators leading up or down to the huge shopping levels. Walk straight through the next set of doors and you enter the spacious and prestigious reception of One Canada Square.

Start walking around to the right and go down the escalator/staircase and turn right through the doors next to Starbucks. This takes you into Reuters Plaza. Pass the restaurants and you will see the Canary Wharf Jubilee line station straight ahead on the left.

The left-hand platform will take you east to Stratford whilst the right-hand platform is for westbound trains to central London.

For the Elizabeth line, continue on with the walk, until you reach Crossrail Place, where you will find the station.

SEEING MORE OF CANARY WHARF

While you’re here you might want to see a little more of Canary Wharf before you leave. If so, I suggest that you continue across the North Dock bridge to West India Dock quayside.

Once across, if you wanted to take a look inside the Museum of London’s Docklands then turn to the left – it’s almost at the end of the line of warehouses. Be warned – there’s a lot to see!

You’ll notice a couple of boats moored to the left – one of these is actually a church. It’s run by St Peter’s Docklands Church, which we saw in Wapping Lane at the beginning of the walk.

Canary Wharf lies within the parish of St Anne’s Church in Limehouse. As more and more businesses relocated to Canary Wharf, the church began running lunchtime meetings and mini-services in pubs and wine bars in the area for those working there, supported by St Helen’s Church in Bishopsgate. Land and property prices were simply too high to consider building a new church, so the result was the setting up of the St Peter’s Canary Wharf Trust and in 2003 the purchase of a Dutch barge. This barge now has a permanent mooring here in West India Quay. A full-time Church of England minister was appointed to head the clergy and the ‘floating church’ now has regular lunchtime meetings and services for local Christians.

If you still have time, then after crossing the North Dock bridge, I suggest you turn to the right, and walk past the restored cranes and the huge Marriott hotel.

Ahead you’ll see the bridge that carries the DLR line across the dock – and what you see on the bridge is actually the West India Dock station. So if you need to head back to central London on the DLR then simply go up the steps and onto the platform.

However, if you still want to carry on or if you’re going back by the Elizabeth or Jubilee lines, then walk under the bridge – we’re heading for the unusual structure you can see in the dock on the other side of the bridge. The large, strange looking grilles where it says ‘Big Easy’ are actually the ventilation units for a station underneath.

This is Crossrail Place, a quite remarkable building which when I saw it being built, with a strange almost ‘bubble-wrap’ looking roof being place on top, I had no idea what it could possibly be! It turned out to be the Canary Wharf station on the new Elizabeth line. Due to have opened in 2019, the complexity of the project was such that it was delayed for three years, opening in May 2022.

Named in honour of Queen Elizabeth II, the Elizabeth line links Reading, Heathrow and other stations to the west of London through to stations in both Essex and south-east London. It passes underneath central London, with new stations linked to existing stations including Paddington, Bond Street, Tottenham Court Road, Farringdon, Liverpool Street and Whitechapel, where the line splits – the one passing through Canary Wharf travels on to Abbey Wood in south-east London, whilst the other travels through to Shenfield in Essex. During busy times there are up to twelve Elizabeth line trains an hour in each direction through Canary Wharf station.

Obviously, if you now want to head back to central London, then the Elizabeth line is good choice.

The actual station was ‘sunk’ down into the dock in yet another of the many clever engineering feats that has made the construction of the Elizabeth line so amazing. If you have seen one of the television documentaries about the building of Crossrail, then you’ll know what I mean.

But the Crossrail Place complex is far more than just a station; there are five storeys above the water level, offering shops, restaurants, a cinema and much more. It was designed by the world-famous architects Foster + Partners, who also designed the Kai Tak cruise terminal in Hong Kong that’s also situated in a ‘dock’ and said to have similar features. They also designed the Jubilee line’s imposing Canary Wharf station, the HSBC Tower, whilst away from Canary Wharf some of their other spectacular buildings in London include the Gherkin and City Hall.

However, it’s the roof that I find particularly spectacular, which is where we are headed now.

To enter Crossrail Place walk up the steps or ramp. Depending on the level on which you enter, you’ll see a very modern looking covered passageway that connects through into Canary Wharf – we shall be passing through this when we leave, but first, take the escalator or stairs to the floor above, where you’ll be in for a very pleasant surprise.

The roof of the complex has been turned into an amazing garden, with flowers, shrubs and trees from all over the world. In addition, at each end are two large bar/restaurants – the ‘Big Easy’ and the ‘Giant Robot’. There’s even a sixty-seat performance area that’s used for a wide variety of events.

To take a look around the garden I suggest you start by walking to the right; follow the right-hand path to the end where you’ll find The Giant Robot, a large, open-plan bar and restaurant. Looking out from the open terrace at the rear of the Giant Robot you can see how much land is still waiting to be developed here. And the long building that runs adjacent is currently the Billingsgate Fish Market. It moved out from it centuries old position on the bank of the Thames, close to the Tower of London, to here in 1982, but it looks like it’s on the move once again, this time to a new market development area further out of London to the east. It’s currently on a thirteen-acre site that’s now extremely valuable, so I’m sure developers will be fighting to get their hands on it once the market has gone.

Walk back down on the other (right-hand side) and when you reach the far end, you’ll find the ‘Big Chill’ – an enormous restaurant, with a small bar.

When you’re ready to leave, take the escalator or stairs back down to the floor below and turn left, walking through the interestingly designed covered Adams Plaza Bridge that brings you out on the opposite side of the road where One Canada Square, Canary Wharf’s principal building, soars 770 feet above you.

Cross over the road and walk to the left and then walk up the short flight of steps or ramp and you are in Canada Square Park. This large open space has a multitude of uses throughout the year. In the winter it’s a huge ice rink; in summer they erect giant cinema screens and show many sporting events such as Wimbledon, as well as live concerts and much more.

As you can see, there are plenty of bars and restaurants to satisfy the needs of local office workers and on a summer evening you’d be amazed at how busy it all is. In the building overlooking the square on the far side is a Waitrose store, said to be their largest in Britain, whilst on the higher floors is the Plateau Restaurant; its floor to ceiling windows give diners some great views of what’s going on below, particularly when events such as the ice skating rink are taking place in the square below.

Finish: Canary Wharf station |

If you’re planning on catching a tube train, then head for the Canary Wharf Jubilee line station – walk across to the other side of the square from where you came in and turn right down South Colonnade and you shortly come to a flight of steps on your left.

Go down the steps into Reuters Plaza (so named because the building on the right is their head office – and you can’t miss the illuminated rolling news board above you.) Pass the restaurants on the left and bars on the right and just after the ‘Middle Dock’ you will see the Canary Wharf Jubilee line station on the left.

The left-hand platform will take you to east to Stratford whilst the right-hand platform is for westbound trains heading into central London. And just an aside – you can’t fail to notice the brutalist architecture, similar to several other Jubilee line stations.

If you are planning on returning by bus, then simply carry on walking down South Colonnade which eventually runs into West Ferry Avenue, where we saw the bus stops earlier. Equally, the DLR station is only a short distance away.

A final point: as you may have already realised, the lower levels of Canada Square and Cabot Square contain scores of shops. All the high street brands are here – together with numerous restaurants, bars and coffee shops. So if you’re in no hurry to head back, then there’s plenty to entertain and interest.

Since creating the above page I have walked and researched a tour of the Canary Wharf Estate (as it’s known), taking in all the key sites, as part of a walk around the Isle of Dogs. To view this walk, please click here.