Updated: 9 September 2019 |

|

Walk page: Click to view |

Wapping to Canary Wharf appendix

MORE ABOUT KEY PLACES ON THE WALK

Extra information on some of the most significant places (especially Limehouse) and stories mentioned in the Wapping to Canary Wharf walk. Illustrated with photographs and contemporary drawings.

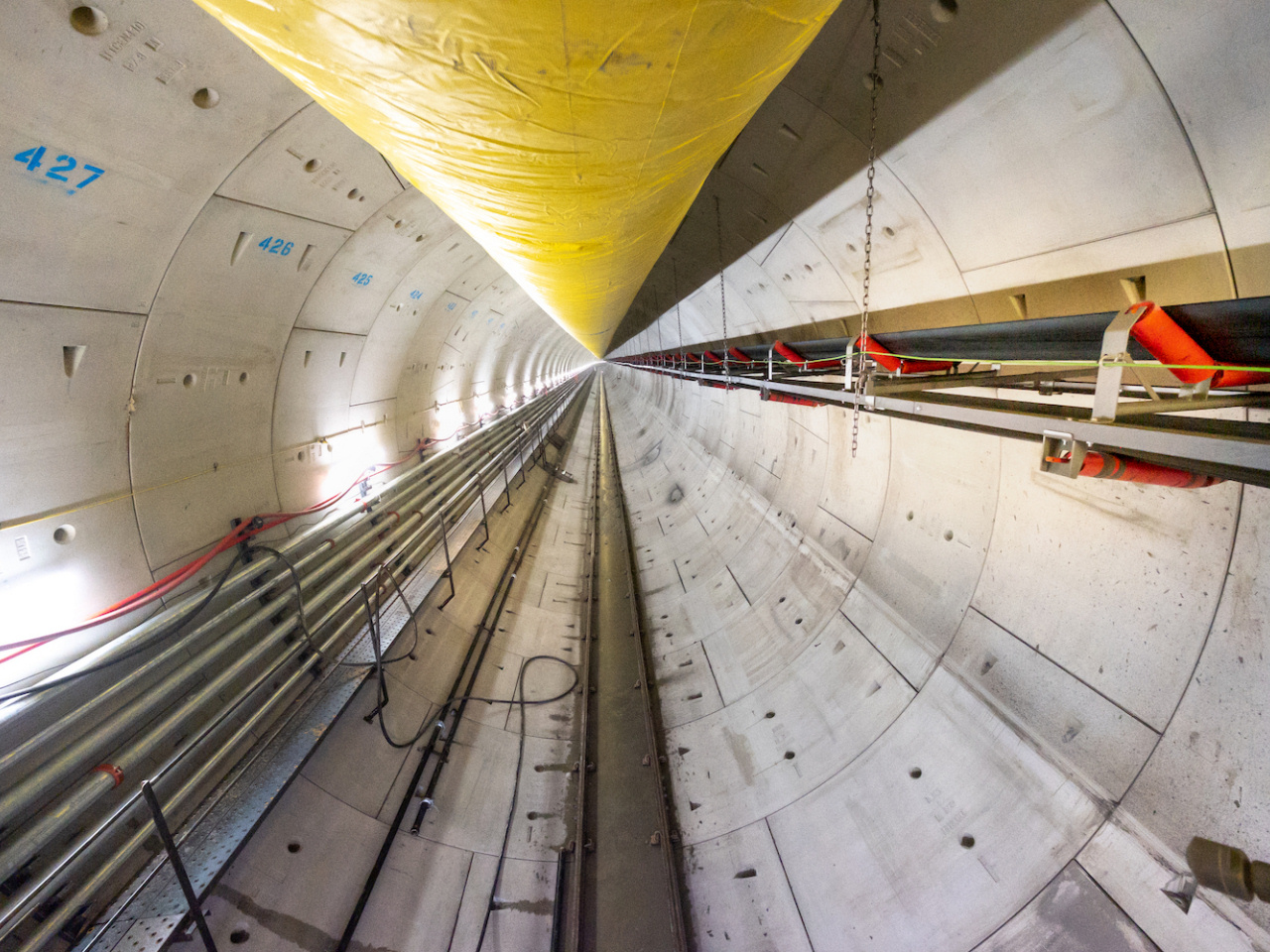

THE THAMES TIDEWAY TUNNEL (otherwise known as the ‘Super Sewer’)

Like many old cities around the world, most of London is served by a ‘combined’ sewerage system, which collects not just the sewage from loos, sinks, showers and washing machines, but also the rainwater run-off from roads, gutters and pavements – hence, ‘combined’.

The magnificent system we rely on today was designed by Victorian engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette after London was hit by periods of horrendous smells, culminating in the ‘Great Stink’ of 1858, when for weeks on end the smell from the River Thames was so bad that people couldn’t bear to be anywhere near it and even Parliament had to be closed.

Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s design used London’s natural drainage system of ‘lost rivers’ – including the Fleet and the Tyburn which had been built over before Victorian times, to flow into his new sewers and on to balancing tanks in east London. However, during severe storms and times of heavy rainfall, the system was designed to overflow into the River Thames, rather than flooding streets and homes. In Bazalgette’s day, this happened once or twice a year. Now, this happens on average most weeks.

Thanks to Bazalgette’s insistence on the highest possible standards in building the 1,100 miles of underground sewers, they are still in excellent condition, but now simply lack the capacity to meet the demands of modern-day living. In the mid-nineteenth century, more than two million people lived in London. Bazalgette had the foresight to design his system to serve four million, but today the city’s population is nearing nine million – and continues to grow. (for which over 318 million bricks were used during construction.

Not only were there fewer people living in London in the 1850s, but they also used less water per person and there was considerably more green space available to soak up rainfall. This meant that overflows occurred only very occasionally. Now it can happen almost every week, and as a result, millions of tonnes of raw, untreated sewage overflows the system and spills into the Thames each year. Needless to say, the effect on the river’s fish, birds and aquatic mammals is quite profound.

The Tideway Tunnel ranks in size of project with the building of the original London Underground system, the Channel tunnel and the currently under construction Crossrail (Elizabeth line) and it is said it will solve the problem of pollution in the Thames for the next 100 years. At the moment, 39 million tonnes of sewage enter the Thames every year and this tunnel will take around 95% of it. It won’t replace Joseph Bazalgette’s amazing original 160-year-old sewage system, but will support it.

Three huge 80ft-wide shafts have been sunk some 190ft deep below the Thames to enable some of the biggest tunnelling equipment in the world to bore a 23ft-wide tunnel that will travel for more than 20 miles under the Thames and its foreshore.

The tunnel will begin in Acton in west London and travel under London at depths of between 100 and 300 feet, using just gravity to move the waste material to Beckton in the east.

It will be nearly as long and wide as the Channel tunnel, cost around £4.2 billion and when it is finished in 2023, will carry millions of tons of raw sewage away from much of London to Beckton in the east, where it will be treated before being allowed to flow back into the River Thames.

Along the way, five million tonnes of chalk, gravel and clay will have to be removed, and the main tunnel will connect to 22 other new tunnels that need to be built to carry the sewage from various points along the river. Ventilation shafts, maintenance buildings and other works will all be needed.

Thanks to Tideway (Bazalgette Tunnel Limited), who are constructing the tunnel, for some of this information.

LIMEHOUSE

Like neighbouring Wapping, I find the history of Limehouse to be fascinating. So I make no apology for the amount I have written here about the district.

To make it easier to read, I have broken into sections – the history; the story of Chinatown; literary and artistic Limehouse; the Limehouse Basin and the Limehouse Cut.

History of Limehouse

Limehouse was one of the few healthy areas of dry land along the riverside marshes and it is believed there has been a settlement here since Saxon times

The name comes from the lime kilns (or oasts to use their original old English name) that were established here in what became known as Limekiln Dock. They were built in the 14th century to burn chalk and limestone in what was then a rather desolate place on the bank of the Thames. The chalk, which was brought by boat from Kent, was used to produce quick lime, originally for plastering wooden buildings and then for building mortar. Later, pottery was made here and in 1660 Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary a visit to the porcelain factory. In 1740 the first ‘soft paste’ porcelain factory was established on what is now called Limekiln Wharf. (Soft paste was a way of making high-grade porcelain).

Due to a combination of tides and currents at this point on the Thames, Limehouse became a natural ‘landfall’ for ships and from the 13th century onwards ships began to moor here to unload. By the time of Queen Elizabeth l, its position on the Thames had resulted in it becoming a significant port, with extensive docks and wharves and industries such as shipbuilding, ship chandlering and rope making being established there. By early in the reign of James l about half of the 2,000 population were mariners. It became a vital part in Britain’s exploration of the world with a number of sea captains and explorers living in the area. Sir Humphrey Gilbert, the Queen Elizabeth l’s favourite explorer, sailed from Limehouse whilst from directly below the Grapes Inn Sir Walter Raleigh set sail on his third voyage to the New World.

As Britain’s maritime industry grew, so Limehouse became known as a centre for ship building, but as ships became too large to be built here, they developed a reputation for building lifeboats, with Forrest’s Yard producing over one hundred of them for the RNLI alone. This began to decline in the late 19th Century when the demand for space for unloading ships became more important than actually building them and the shipbuilding moved elsewhere.

It was always an isolated place …

To me one of the attractions of the part of Limehouse that we walk through is its relative peacefulness – The Highway, a fast ‘Expressway,’ out of London runs into the Limehouse Link Tunnel just a couple of hundred yards north of Narrow Street. This means that the southside of Limehouse is not actually a through route to anywhere, yet just a few hundred yards away is one of London’s busies areas.

With marshes on one side and the river on the other, Limehouse had always been a somewhat isolated place and for a long time a boat was the only practical method of travel. Eventually the marshes were drained and a road – now known as the Highway, which we have previously mentioned, was built on the top of the banks, linking it with London. However, it was the building of Commercial Road in around 1810, together with the opening of the London to Blackwall Railway in 1840 that led to further growth. It meant that rather than cargo having to be transferred into small boats to be taken to London, it could now be taken by road, although of course these were still generally in a very poor condition.

A predominantly working-class area –

Like much of the east of London, Limehouse was a predominantly poor working-class area, but due to the maritime industry it had a surprisingly large population – some 2,000 by 1610 and by the 1700s over 7,000. Besides those working in the area there were always huge numbers of sailors living in Limehouse, many for just short periods whilst they were waiting for work. At first, they mostly lived in terrible ‘slum’ accommodation, often ten or more to a room, but by the end of the 19th century many hostels had opened, one of the biggest being the Empire Memorial Hostel that had beds for 300. Although it didn’t open until just after the First World War, by the 1930s it is said that over 200,000 seamen had stayed there. With a café, library, concert hall and even a mini ‘seamen’s job centre’ its facilities were very good. However, many hostels weren’t so good – in fact many were disgusting and some literally existed just to ‘rip off’ vulnerable foreign sailors who rarely spoke the language. Sailors had often been at sea for weeks or maybe months so when they left their ship, with their unspent wages for the voyage ‘burning a hole in their pocket’ they often headed for the nearest pub – and brothel – or both. Needless to say they were an easy target for local villains, of which there were plenty, and they often did lose everything – and some even their lives – that first night ashore.

The brothels –

It is said that in the 1860s there were nearly 3,000 brothels in London’s East End – and that didn’t include the thousands of women who ‘entertained men on a part-time and not a professional basis who were called ‘dolly mops’. It was a rough area; violence, drunken brawls, and even murder were an everyday occurrence and usually not considered worth reporting or being recorded – it was just very day life in docklands

Whilst most of Limehouse was poor, the area around St Anne’s Church once had some rather splendid houses, predominantly owned by local ship owners and ship’s captains. But as time went on this began to change and by the 1860s the rector of St Anne’s said “the parishioners are for the most part poor, comprising a large number of persons employed at the docks, engineering and shop building yards. There is an increase of low lodging houses for sailors and the removal of the more respectable families to other localities.”

The regeneration of Limehouse –

Like Wapping, the area suffered heavily during the Blitz when over half the houses were either very badly damaged or completely destroyed. The clearance of bombsites and the older streets continued throughout the 1950s and 60s and unfortunately little now remains of this historic and previously important part of London. Indeed, by the 1970s most of the docks had closed and the area from Wapping through to Limehouse and on towards what is now known as Canary Wharf, was a rather sad and forlorn area. Unemployment was high, those wharfs and warehouses that were still standing were empty with some in a dangerous condition.

Then in the early 1980s the Conservative government introduced a regeneration scheme and formed the London Docks Development Corporation. I have covered this separately elsewhere but suffice to say here it had a huge impact on Limehouse, Wapping and of course Canary Wharf and eventually the rest of the Isle of Dogs. The building of the Limehouse Link tunnel had a major – and many would say – fairly negative impact on the area, but a more positive result came from the building of the Docklands Light Railway and the opening of a station at Limehouse.

Indeed, by the 1990s Limehouse was showing signs of becoming ‘trendy’, as more and more of the old warehouses and previously derelict sites were turned into luxury apartment buildings. The ‘yuppies’ had arrived. Many of these new residents were working in offices in Canary Wharf, but it also attracted others who rather liked the ‘off beat’ feel of the area.

Residents now include Evgeny Lebedev, the Russian owner of the Evening Standard and the Independent newspapers, onetime politician Lord David Owen and comedian Lee Hurst. Several well-known actors live in Limehouse, including Sir Ian McKellen, Steven Berkoff and Cleo Rocos. Janet Street Porter lived here until apparently a barge slipped its moorings and crashed through her apartment window! The past relative isolation of Limehouse also proved to be somewhat of an attraction for people looking for somewhere to be out of the limelight, yet with easy access to London. Princess Margaret was said to have conducted her pre-marital affair with Anthony Armstrong-Jones here, as she also did at the Prospect of Whitby. In those days the East End was not as popular with tourists and visitors as it is today, so presumably they felt there was less chance of them being spotted here!

The Story of Chinatown

From the 15th century until the 20th, the majority of ships crews were employed on a casual basis and would be paid off at the end of their voyages.

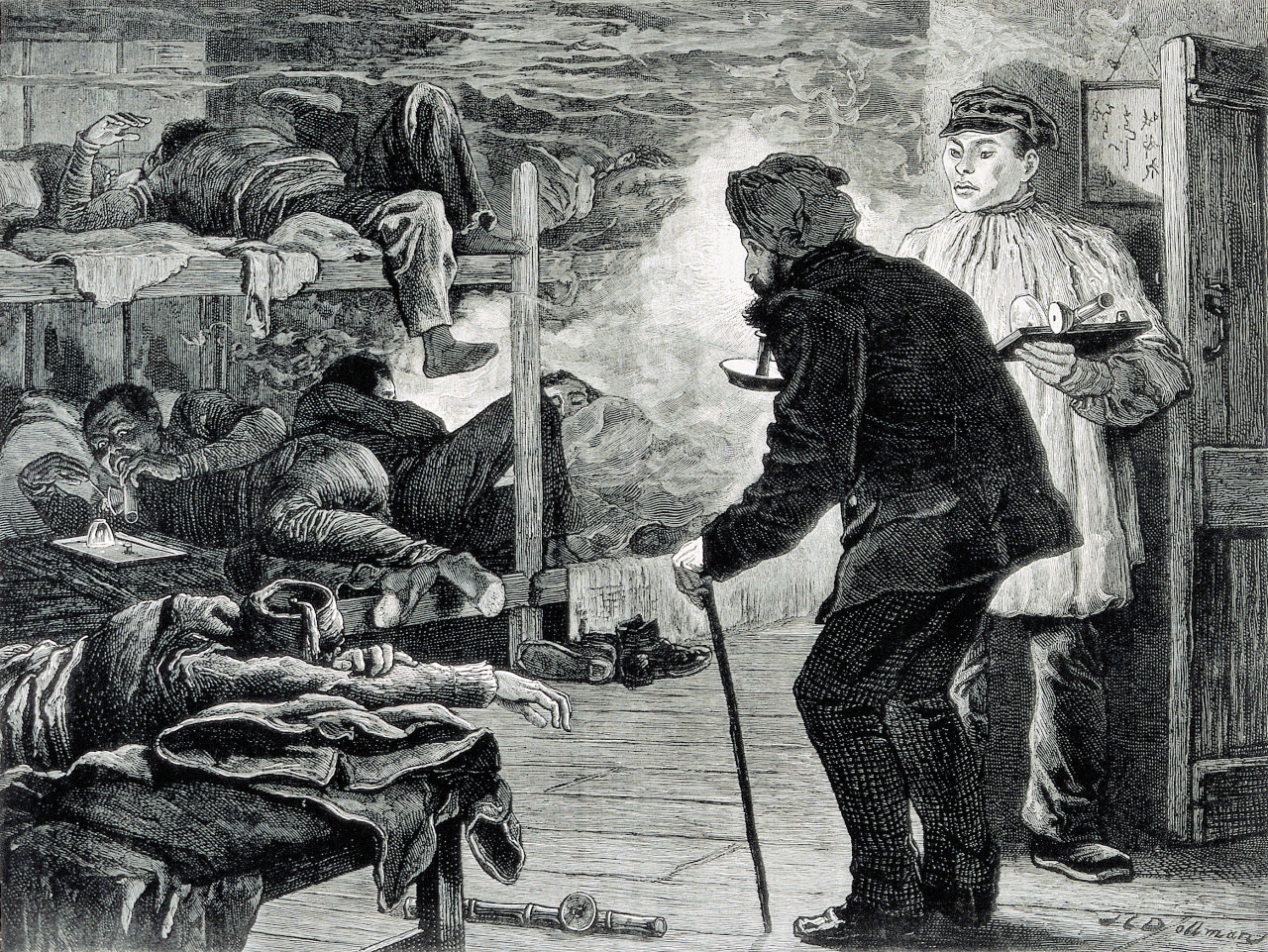

This resulted in communities of foreign sailors becoming established here, including colonies of Lascars and Africans from the Guinea Coast. From about 1890 onwards, large numbers of Chinese sailors, mainly from Canton and South China, began to settle in both Limehouse and Shadwell. Many of them had been working on ships trading in the opium and tea trades and this resulted in the creation of London’s first and original Chinatown. For one reason or another, many were unable or unwilling to return home and so settled here. Besides the opium, they began to set up gambling dens and both soon attracted a wider clientele than other visiting Chinese sailors.

‘Legendary Chinatown’ actually consisted of little more than two streets, Limehouse Causeway and Pennyfields, which straddled the West India Dock Road. By the early 20th century it had become the focus of rumours and myths about opium dens, gambling and sexual vice. Whilst some of this no doubt existed, in reality it was a fairly peaceful place and became one of London’s earliest multicultural communities.

Authors such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Oscar Wilde luridly described events here and I particularly like this description of an opium den, taken from a book called ‘Oriental London’ written by Count E. Armfelt –

“There are mysterious looking shops in Limehouse with little or nothing in the window, and which have curtains to shut off the street. Now and again a Chinaman or other Asiatic will push the handle and disappear. It is an opium-smoking room. Enter and you will see a counter, a pair of small scales, a few cigars, some tobacco, and other etceteras. The shop has a back parlour with a dingy yellow curtain. It is finished with a settee, chairs and a spacious divan, or wooden structure with one or two mattresses and half a dozen hard pillows or bolsters. It is there that the Ya’pian Kan – the prepared opium – is smoked, and the majoon, made of hellebore, hemp, and opium, is chewed, eaten and smoked.

(I mention more of the writings about the Chinese in Limehouse in the next section – ‘Literary, artistic and musical Limehouse’.)

Over the years the Chinese began to open eating houses catering for the needs of their own community who wanted to enjoy Oriental cuisine, and this began to attract other Londoners who were interested in trying these ‘foreign foods’. After the end of the First World War there were concerns that the Chinese in Limehouse were taking the jobs of those who had gone away to fight overseas, as well as concerns that some of them were involved in the ‘White Slave Trade’ and this resulted in some small scale ‘anti-Chinese’ riots in 1919.

However, it was following the serious damage done by bombing raids on Limehouse during the Second World War that many Chinese families began moving out and relocated to Soho, eventually opening restaurants. And Chinatown as we know it was born!

Literary and artistic Limehouse

Limehouse has always attracted literary interest – possibly because of the Chinese ‘opium den’ connection. Charles Dickens’ last book, ‘The Mystery of Edwin Drood’, includes an account of a visit to a local opium den. Oscar Wilde featured it in ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’, where Dorian heads to an opium den. Arthur Conan Doyle sent Sherlock Holmes in search of opium provided by the local Chinese immigrants.

The Chinese connection was featured in Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights, a collection of stories set in the area with a Chinese narrator Quong Lee. In Arthur Ward’s books (writing under the pseudonym Sax Rohmer) he tells the story of Fu Manchu, who of course has his hideout in a Limehouse opium den. Indeed, the ten or so books he wrote significantly added to the notoriety of Limehouse!

George Orwell wrote about a lodging house in Limehouse in ‘Down and Out in Paris and London’, whilst more recently Peter Ackroyd includes the area in ‘Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem’.

Dickens was a regular visitor to this area. His godfather lived in Newell Street, just a few hundred yards from Narrow Street, where he was a sailmaker.

In ‘Our Mutual Friend’ Dickens wrote of walking by the river and hearing ‘The turning of steam paddles … the clinking or iron chains…. the cracking of blocks …. the measured working of oars … the occasional violent barking of some passing dog on ship board’.

In Chapter 22 of the ‘Uncommercial Traveller’ he wrote a wonderful description of life ‘down by the docks’ … “Down by the Docks, they ‘board seamen’ at the eating-houses, the public-houses, the slop-shops, the coffee-shops, the tally-shops, all kinds of shops mentionable and unmentionable – board them, as it were, in the piratical sense, making them bleed terribly, and giving no quarter. Down by the Docks, the seamen roam in mid-street and mid-day, their pockets inside out, and their heads no better. Down by the Docks, the daughters of wave-ruling Britannia also rove, clad in silken attire, with uncovered tresses streaming in the breeze … Down by the Docks, you may buy polonies, saveloys, and sausage preparations various, if you are not particular what they are made of besides seasoning. Down by the Docks, the children of Israel creep into any gloomy cribs and entries they can hire, and hang slops there – pewter watches, sou’-wester hats, waterproof overalls – ‘firtht rate articleth, Thjack.’ … Down by the Docks, scraping fiddles go in the public-houses all day long, and, shrill above their din and all the din, rises the screeching of innumerable parrots brought from foreign parts, who appear to be very much astonished by what they find on these native shores of ours.”

Artists

Narrow Street is also associated with many distinguished painters. One of the most prolific painters of Limehouse and the river was Charles Napier Hemy, who went on to become one of Britain’s most famous marine artists. He was born in 1841 in Newcastle upon Tyne and always remembered the day when at the age of ten, he and his family sailed to Australia, saying, “I can remember it (the open sea), it entered my soul, it was imprinted on my mind, and I never forgot it’.

Several of his paintings were of the picturesque wooden buildings, the barges, wharfs, warehouses and inns of Limehouse, Wapping and Rotherhithe and, together with the barge men and labourers who worked there. One of the most well-known is his 1877 painting of the ‘Limehouse Barge Builders’, which he later said he did ‘from nature, sitting in a barge and talking with the workmen’.

Several other artists have used Narrow Street and the riverside around Limehouse in their paintings, including James Jacques Joseph Tissot and the American born artist James McNeill Whistler. In the 1860s Whistler lived near the docks in Wapping and a painted a number of local scenes, including a major oil painting I particularly like that’s entitled ‘Wapping on Thames’ (shown above).

And it wasn’t just books and paintings; a popular early 20th century musical hall song tells of ‘Limehouse Liz’, including the (now offensive) verse –

… then she drifted down to China Town

And you all know where that is

Where slitty-eyed Chinks take 40 winks

And she’s known as Limehouse Liz.

Finally – another musical connection – the area inspired the famous jazz number ‘Limehouse Blues’, which was later featured in Fred Astaire and Lucile Bremer’s musical Ziegfeld Follies.

Limehouse Basin

The Limehouse Basin (originally called the Regent’s Canal Dock) opened in 1820 to enable ships to unload cargo and be put on to shallow-draught barges and be taken up the Regent’s Canal, which opened that same year.

It also provided the same facility for barges using the Limehouse Navigation – or Cut, as it is more commonly known. These would have previously just sailed out through a much narrower lock than the new basin had and out into the Thames to load or unload.

(I have written more about both the Regent’s Canal and the ‘Cut’ below).

It was a busy place; around 1,500 ships and over 15,000 barges are said to have used the dock in 1865 alone and this success prompted it to be enlarged several times. As ships grew larger, the original lock entrance was found to be too small and a bigger ‘ship lock’ was built a couple of hundred yards to the west (the site of the present lock).

Three of the basin’s major imports were coal, timber and ice. Coal from Northumberland and Durham would arrive on ‘collier brigs’ to supply the factories and gas works that were built along both the river and the canal and gangs of ‘coal whippers’ would shovel it into baskets – tough work for the men and it could take up to a week to unload just one barge. This was considerably speeded up when hydraulic cranes were introduced in the 1850s.

Timber came from Finland and Norway and was stored on the Bergen and Medland Wharves on the left side of the basin. Ice came from Scandinavia and there were around fifteen shiploads a year. It was unloaded here and taken by barge to the ice stores on the Regent’s Canal near Kings Cross. It was expensive, but a valuable asset to fishmongers, butchers and of course ice-cream makers. The ice stores were often below ground, with thick stone walls and lined with straw. The King’s Cross ice store is now the home of the London Canal Museum, with some very interesting exhibits on all aspects of the trade on the waterway.

The basin finally closed to commercial traffic in 1969 and became a marina in 2001.

Limehouse Navigation (or Cut)

The Limehouse Cut, which runs from Limehouse Basin to Bromley Lock, was constructed in 1770 to ease the navigation of barges travelling on the River Lea from Hertfordshire to the Thames. The Lea actually flows into the Thames several miles further east – opposite the 02 – but navigation was difficult because of sharp bends and continual silting. The Cut also avoided the journey around the Isle of Dogs for barges heading for London itself.

It was an important waterway – barges brought grain and malt to London and later raw materials from the docks in London would be taken back up river to the many mills and factories that lined its banks. It was the first canal to be opened in London and one of the oldest in England.

REGENT’S CANAL

The Regent’s Canal, which opened in 1820, creates a link between the Thames and Britain’s canal network. It runs from Limehouse Basin and around the east and north of central London to Little Venice, close to Paddington. There it links to the Grand Union Canal. It’s a journey of about 8½ miles and takes about five hours to walk. Boats, which generally travel at walking pace, would have taken considerably longer as they had to navigate the thirteen locks and, in those days, these would have been very busy and at times boats had to queue.

The canal enabled manufactured goods from the Midlands to be brought down to London and then taken onwards by ships across the world. It also enabled coal that was unloaded on the Thames to be transported from London’s docks to factories and later gasworks in north London.

As with most canals in Britain it was badly affected by the growth of the railways, finding it hard to compete with the far speedier service that they offered. Limehouse Dock finally closed to commercial shipping in 1969 and the Regent’s Canal is now used for leisure boating, as well as being popular with walkers, cyclists and fishermen.

WILLOUGHBY MEMORIAL

The Willoughby Memorial is positioned on the side of the ‘drum’ that acts as a ventilation shaft for the Rotherhithe Tunnel. The memorial commemorates this as being the departure point for several famous explorers who sailed from here in the 1600s.

Colourful ceramic tiles depict 17th century sailing ships and the inscription explains is in memory of Sir Hugh Willoughby, Martin Frobisher and other navigators who ‘in the latter half of the sixteenth century set sail from this reach of the River Thames near Ratcliffe Cross to explore the Northern Seas and discover a north-west passage to Cathay and India’.

The expedition, which comprised of three ships led by Willoughby, was sponsored by the Company of Merchant Adventurers to discover ‘unknown regions’ – primarily a northern route to Cathay and India. His log read – “These aforesaid ships being furnished with pinnaces and boats well-appointed with all manner of artillery and other things necessary for their defence, with all the men aforesaid departed from Ratcliffe and sail unto Deptford the 10th day of May 1553”

Due to bad weather they ended up having to spend the winter in the north of Norway, where they became trapped by ice and he and the crew of two of the ships froze to death. Indeed, only one ship returned – and that hadn’t got any further than the Russian White Sea. But luck was certainly with Sir Martin Frobisher, the Captain of that ship, as he was rescued by locals, and taken from to Moscow. There he met Tsar Ivan 1V, who after I’m sure must have been a little ‘haggling’, gave him exclusive trading rights between Muscovy (Moscow) and London – primarily importing furs, timber and wax.

As a result the ‘Muscovy Company’ was set up, (the world’s first ‘joint-stock’ organisation, which in basic layman’s terms meant private individuals could invest in it, rather than just rich merchants or other companies which had been the case until then.)

The company became extremely wealthy – there is still a Muscovy Street in the City of London where it once had offices and their Russian headquarters, near to the Kremlin in Moscow, were built during the reign of Ivan IV and known as the ‘Old British Yard’.

The Company continued in existence until the Russian Revolution in 1917 and since then it has operated mainly as a charity. There doesn’t seem to be much information about it, but I understand it helps support churches and Anglican ministers in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other cities, including the St Andrew’s Anglican Church in Moscow. Queen Elizabeth visited the ‘Old British Yard’ on her visit to Moscow in 1994.

And as for Sir Martin Frobisher … well, he made a further three voyages to the New World, still searching for the elusive ‘Northwest Passage’. On one of these, in 1576, he reached Labrador, but was sadly disappointed when having returned home with a ‘booty’ of 200 tons of gold, he discovered that what he had brought back thinking his fortune was now secure, turned out to be not gold but iron pyrites (fool’s gold)!

But he never gave up. In 1585 he sailed with Drake to the West Indies and then three years later took part in the defeat of the Armada. Quite an amazing man, who certainly deserves to be remembered here.

RATCLIFF

Ratcliff is no longer the recognisable area that is once was, now just being part of Limehouse. It was originally called Redeclyf, meaning the red cliff, though you might find it difficult to believe there could have been a ‘cliff’ here, and indeed there hardly ever was one, simply just a slight rise in the ground. However, because much of the surrounding land was very flat it was easily recognisable as a landmark by sailors travelling up the river. Indeed, the sighting of Ratcliff was said to be memorable to sailors returning home after long voyages in the 16th and 17th centuries, and there are several references in old sailing logs to “praising God at the sight of Ratcliff”.

A small settlement grew up here in very early times, partly because it was slightly higher than the surrounding land which was mainly marshes and also because at this point the river tended not to silt up. Its situation on a bend in the Thames meant it had a flow of water that was free from eddies.

The first wharf was built here in the 14th century and it became an important place for unloading ships, particularly so when there were ‘plagues’ and other pestilences that meant ships were not allowed further up the Thames and into London for fear of bringing disease into the city. However, as with neighbouring Limehouse, which I have explained elsewhere, there was a big change around the time of Queen Elizabeth l, when it became illegal to unload ships here. The reason for that was the ship owners and merchants had been avoiding paying the duty on imports which had to be paid by all ships being unloaded in the Pool of London, above the present-day Tower Bridge.

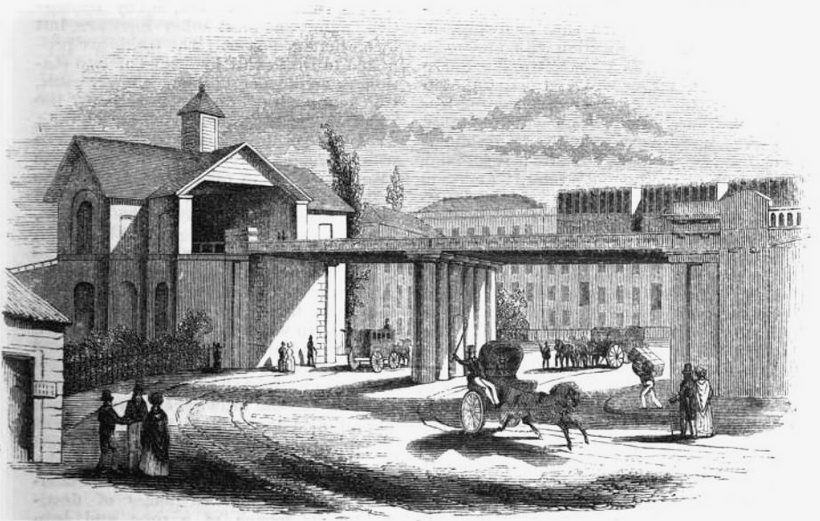

LONDON AND BLACKWALL RAILWAY

On the walk we pass the enormous brick viaduct that now carries the Docklands Light Railway. It’s the second oldest railway viaduct in the world and was built in 1840 by George Stephenson and his son Robert, to carry the London & Blackwall Railway.

This had been built to take passengers from London to the Brunswick Pier at Blackwall, where they could then transfer onto the ferry to Gravesend across the river in Kent, and the steam ships that operated regular services to a number of countries around the world.

It was a rather unusual railway from the beginning. There was a high risk that sparks from a steam locomotive could set fire to the houses that were so close to the line, so they came up with the solution of having two stationary engines at each end of the line which would pull the train by a very long rope! It was hardly surprisingly that the rope would often break, causing big problems for the railwaymen and considerable discomfort to the passengers.

Within ten years they gave up on this method and reverted to having a standard locomotive to pull the train. The line ceased to be used in the early 1960s, and it wasn’t until the Docklands Light Railway came into being that it was brought back into service.

Right from the early days the railway company realised the commercial value of the space in the ‘arches’. It meant they were able to rent or sell the space, an additional form of income, as it still is today for Network Rail who own most of the rail tracks in Britain. Due to a drop in demand for travel to Blackwall the line closed, but was reopened in 1987 to be used by the Docklands Light Railway for trains from Tower Gateway and Bank Stations through to Canary Wharf, Greenwich, Poplar etc.

And I will just put here a few lines from one of my favourite authors, John Betjeman, who in his 1952 book ‘First and Last Loves’, wrote of a journey on the line – “Those frequent and quite empty trains of the Blackwall Railway ran from a special platform at Fenchurch Street. I remember them like stagecoaches; they rumbled past East End chimney pots, wharves and shipping, stopping at empty black stations, until they came to a final halt at Blackwall Station. When one emerged there, there was nothing to see beyond it but a cobbled quay and a vast stretch of wind whipped water …” He must have written that in his late teens or his very early twenties, as he was born in 1906 and the line closed in 1926.

PROSPECT OF WHITBY

This is one of London’s oldest (and my favourite) riverside pubs. Said to be the oldest, it dates back to 1520 – when Henry VIII was on the throne.

Originally called the Pelican Inn, it was usually known as the Devil’s Tavern, allegedly because of some of the wicked activities that went on here. Much of the original building burnt down in 1770 and the rebuilt inn was renamed the ‘Prospect of Whitby’, the name of a collier that used to moor alongside. It would sail from the port of Whitby bringing coals from the mines of Yorkshire for the hydraulic pumping station opposite.

The Prospect is Grade II listed; the flagstone floor is said to be the original and over 400 years old, whilst the pewter bar counter that rests on old barrels, once common in inns, is said to be the longest example still surviving in Britain.

The pub has hosted many famous – and infamous – people over the years, one being the infamous pirate Captain Kidd. Judge Jefferies, who is said to have been responsible for the hanging of several hundred men (as well as sentencing many hundreds more to transportation) – was said to enjoy his lunch on the balcony whilst actually watching pirates being hanged nearby.

Samuel Pepys would visit when he was naval clerk and later Secretary to the Navy (one of the rooms upstairs is named after him); Charles Dickens was another regular. In more recent years Princess Margaret and Lord Snowden used to meet here, and people as diverse as Richard Burton, Mohamed Ali, Paul Newman, Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra, Rob Steiger and Dennis Waterman have all enjoyed drinking or eating here. Indeed, there are photographs of many of these ‘celebrities’ enjoying the pub’s hospitality.

And I can see why they all loved it – I just love the place too! I first visited it in the 1960s, and in nearly 50 years it seems to have hardly changed, though that maybe just my memory! It has fabulous views of the river from the windows – especially from the first floor – as well as from the adjacent terrace. Indeed, the famous artists Turner and Whistler painted some of their finest Thames pictures from here.

One of the rooms upstairs was famous for its boxing matches, and again there are photographs on the wall of those events. Cock fighting also took place in this room.

Throughout the pub there are information boards giving plenty of history about the place, which all adds to its atmosphere and interest. Outside there is a terraced garden that overlooks the river with a plaque that explains that the first fuchsia ever seen in Britain was brought here by a sailor from the West Indies. Apparently, that was in 1696, and the sailor who had brought it back from Santo Domingo traded it for a noggin of rum!

Finally, there is both a good range of beers and wines as well as excellent and reasonably priced food.

WAPPING HYDRAULIC PUMPING STATION

Newcastle engineer William Armstrong introduced hydraulic power into the docks in the 1850s. It used water, pumped under great pressure, to operate swing bridges, lock-gates and cranes. The water was stored in brick towers called accumulators and kept under great pressure by the use of rams operated by steam engines. The water, at seventeen times the pressure of domestic water, was then pumped through specially cast 6’’ to 10’’ inch iron pipes that were laid under the streets.

Originally there were a number of small hydraulic pumping stations, but the setting up of the London Hydraulic Power Company in 1883, meant this was uneconomic. They opened the Wapping Hydraulic Pumping Station in 1893. Besides lifting bridges, operating the dockside cranes and providing power to machines in factories, they also provided the power to operate the very first lifts in places such as the Bank of England. Some of the other more fascinating uses were to provide power to open and close the curtains and raise and lower stages in theatres such as the famous Theatre Royal in Dury Lane and the Royal Opera House in London’s West End. Shops, offices, mansion houses … all benefited by the introduction of hydraulic power in London.

The London Hydraulic Company built five such pumping stations and this one was the last to close, which it did in 1977. It was originally operated by steam engines, but the pumps at Wapping were later converted to electricity.

A surprising amount of the original complex still remains, including the engine house, boiler house, water tanks, accumulator tower, a number of pumps, cranes, the foreman’s house and more.

The company had around 180 miles of pipes buried under London streets and the value of this network was quickly recognised when the ‘cable communication revolution’ began to happen – the company had statutory ‘wayleave’ rights that entitled them to dig up streets, similar to the rights owned by gas, water and electricity companies, so it was eagerly purchased by Mercury Communications, a subsidiary at the time of Cable and Wireless and now Liberty, the owners of Virgin Media.

ST ANNE’S CHURCH

I mention St Anne’s, the magnificent Grade I listed parish church of Limehouse and although we don’t visit it on the walk, it’s just a ten-minute stroll from the point in Narrow Street where we turn right into Three Colt Street.

It is one of ten London churches built as a result of an Act of Parliament in the 18th century authorising the construction of three hundred more churches across the country (although not all were built) because of concerns that there weren’t sufficient churches to meet the needs of the expanding population.

It was named after Queen Anne, who in order to raise the money to build it, had increased the tax on coal brought up the River Thames – which must have been a very unfair additional burden on the many extremely poor people in London.

After it had been completed in 1725, Queen Anne decreed that as it was so close to the river then it would be a good place for ship’s captains to register important events that were taking place at sea. As a result, the church was given the right to display the White Ensign – and not just on special occasions, but at all times. This is rare as this flag, which is the second most senior ensign of the Royal Navy, can normally only be flown at special occasions. The ensign is still flown on the church tower and the maritime connection still exists as its current rector is honorary chaplain to the Royal Navy.

The church was one of six built in London by the famous architect Nicholas Hawksmoor, a pupil of Sir Christopher Wren and at one time his assistant. He also built the nearby church of St George in the East at Shadwell and Christ Church in London’s Spitalfields, another particular favourite of mine.

It is shaped like a Greek cross, with Corinthian columns and an elongated nave. All his churches were remarkable, especially their towers and St Anne’s was no exception. At 200 feet high it’s the tallest in London and the second highest Gothic-style clock tower in Britain – only Big Ben is higher – and it’s topped by a very distinctive, highly decorated ‘golden ball’ and octagonal lantern, which I explain more about in the next section.

The church was badly damaged by fire in 1850 and rebuilt several years later, again in the Portland Stone that helps give it such a striking appearance. St Anne’s is also famous for its very historic organ, which won first prize at the 1851 Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace, and to this day is still very popular with organists. More recently the church has been used in a number of TV programmes, including the recent ‘Call the Midwife’.

Finally, after the opening of Canary Wharf as a major business area, the congregation of St Anne’s considered building a sister church there, but land became so expensive it was impossible. However, they found a unique way to do their outreach work and bought a Dutch freight vessel over from Holland. Called St Peter’s Barge they converted it into a floating church that is now moored in Canary Wharf. And interestingly it also has permission to also fly a naval flag – in this case the blue ensign. You can see it if you visit West India Quay in Canary Wharf.

St Anne’s Church tower

It was vital for ship’s navigators to know the exact time as this was how they determined a ship’s position at sea. To assist ships on the Thames to set the accurate time, the Royal Greenwich Observatory, which is situated on a hill on the other side and a little further down river, would ‘drop’ a weight, in the form of a large red ball, from the top of its tower at exactly 1pm each day.

St Anne’s Church tower is in direct line of sight from the observatory and as soon as they saw its red ball drop, they would release their golden ball, enabling ships that couldn’t see Greenwich to set their timepieces. The golden ball was deliberately made a different colour from the Greenwich time ball to avoid any confusion.

As I’ve already said, it is the highest church clock in London and had the first illuminated clock face in Britain. Its height meant it could be seen by the many hundreds of ships moored or sailing up or down the river. However, in case of misty days, which of course being so close to the river were common, the clock also used to chime – four times an hour! (Probably because of complaints from the people living in the new, trendy apartments nearby, it no longer does.)

Until recently the golden ball on the flagpole above the tower, which also acts as part of a weather vane, was an official Trinity House ‘sea mark’ on navigation charts. And again as I’ve already said, the Queen’s Regulations still allow St. Anne’s Limehouse to display the White Ensign 24 hours a day.

(And interestingly, Hawksmoor’s original design for the tower had a pyramid on its top. The pyramid was built but was put in to the church garden, where it still is today.)