Updated: 29 July 2022 |

|

Walk page: Click to view |

Charing Cross to St Paul’s appendix

MORE ABOUT THE WALK’S SIGHTS

In-depth profiles of some of the most significant places and people mentioned in the Charing Cross to St Paul’s walk, together with photos and old prints.

CONTENTS

Thames Embankment

London’s sewers

The Savoy

Waterloo Bridge

Temple Bar

The obelisk on the Embankment

Arthur Sullivan

Charles Dickens

Somerset House

Child and Co.

St Dunstan-in-the-West

Serjeants’ Inn

Fleet Street and newspapers

St Bride

Fleet Street and the printing industry

Paternoster Square

St Paul’s Cathedral

THE THAMES EMBANKMENT

The man responsible for the Embankment which runs alongside the Thames through much of London was Joseph Bazalgette, who was the Metropolitan Board of Works Chief Engineer. (This was the body responsible for trying to cope with the astonishing rise in population of London and the problems it created from the mid-1850s until the London County Council was formed some forty years later.)

With the huge growth in London’s population and drains gradually beginning to replace cesspits, the city faced a growing problem with its sewage. It had always eventually ended up flowing into the River Thames, which wasn’t so much of a problem in the winter, but it certainly was in the summer, when much less water would flow into the river from the hills in the Cotswolds where it rose and along the Thames Valley. The other problem was the monthly ‘Spring Tides’ (which don’t just happen in the spring). When these occur, the water in the Thames can’t ‘empty’ as sea water is pushed further up the river, making it virtually stagnant at times. The problem became increasingly worse throughout the 1850s, with over ten thousand dying from outbreaks of cholera in one year alone.

The problem came to a head in the summer of 1858 – the year that became known as ‘The Great Stink’, when a scorching hot summer saw temperatures average 35 degrees and the Thames hardly flowed. The result was a stench which saw ferries and watermen unable or refusing to take to the river and Parliament having to be adjourned for a time. It was probably that which forced members of Parliament to realise that something had to be done. Initially many tons of lime were spread on the foreshore of the Thames and at the outlets of rivers and streams that discharged into it, but this had no effect. Within two years Parliament had passed a bill declaring that a proper sewage system had to be built.

The man appointed to come up with solutions was Joseph Bazalgette and he proposed building a whole new network of sewer systems.

The facts are mind boggling. He constructed 13,000 miles of small sewers, which led into 450 miles of main sewers. These in turn fed into six main ‘interceptor’ sewers totalling 100 miles, several of which drained into an enormous sewer that was built along the foreshore of the Thames, taking the sewage many miles eastwards down the river, eventually ending up in two enormous pumping stations well away from London – one on the north bank of the Thames at Abbey Mills and the other on the south bank at Deptford.

Bazalgette insisted on constructing wide egg-shaped, brick-walled sewers rather than pipes, which meant the sewage would flow more easily and have the space to carry more as the population grew. And this is the sewer system that London still relies on today. And so good was his engineering that much of it is still in excellent condition.

Why was the Embankment built as part of this?

There were three reasons for the construction of the Embankment. Principally, it was to cover the enormous main sewer that Joseph Bazalgette built that ran alongside the river. But at the same time it enabled an underground railway line to be built under it – another link in what became the Circle line. Thirdly, with a new road being built on it, it helped to ease some of the traffic problems (they certainly aren’t just a modern invention) in the congested streets, the Strand being just one example. And as a spin-off, it also meant that the appearance of the bank of the river was considerably improved.

In total 38 acres of riverside were reclaimed and the new road with gardens behind it built on top. Subsoil from the Circle line excavations, together with topsoil that was brought up from Barking Creek, further down the Thames, were used to fill in behind the granite wall that was built to line the river and create the Embankment as we now know it.

The design of the main Villiers Street section of the gardens (through which we walk) was much as it is today, with paths and a large number of flower beds. Deciduous trees and shrubs were chosen because of the beauty of their spring and summer foliage. And because they were more likely to withstand the ‘injurious effect of the smoke laden atmosphere’. They also had to withstand Victorian vandalism. Indeed many had to be replaced before they could gain their full stature. The design of mounds, winding paths and flower borders to shrubberies was criticised in the architectural press as being too rural. A central avenue of trees with only one large terracotta pot of flowers was suggested as more appropriate. The original designs had a fountain at the west end of the present central flower beds. A temporary wooden bandstand and seating area was constructed over a semi-circle of the flower beds. In the 1970s the regular lunch-time concerts were popular with office workers.

LONDON’S SEWERS

Following the ‘Great Stink’ in 1858, when Joseph Bazalgette built the new sewers, (which I have written about above) there were just under three million people in London, so although he designed the sewers with at least twice that population in mind, it is now over nine million!

Besides building a network of sewer tunnels across London, Bazalgette’s other brilliant idea was a giant ‘super sewer’ that ran along the side of the Thames to pumping stations further to the east of London, where it would then enter the Thames.

However, whilst in the 19th century people rarely took baths, most of us now take a shower or bath on a daily basis and all houses now have flushing toilets. In addition, London then had far more ‘green space’ than it does today, with houses, office and factories built on what was then open land and now many household gardens no longer exist and have now been paved over, meaning when there is heavy rain it no longer soaks into the ground, but instead goes straight into the sewers.

As a result of all this, over the past few years there have been an increasing number of occasions when Bazalgette’s ‘super sewer’ just can’t cope and the effluent has to be discharged into the river, just as it had been all those years before. Indeed, its estimated that almost 40 million tons of it now flow into the Thames each year. Which in these times of much greater environmental concerns has of course has become unacceptable.

The Tideway Project

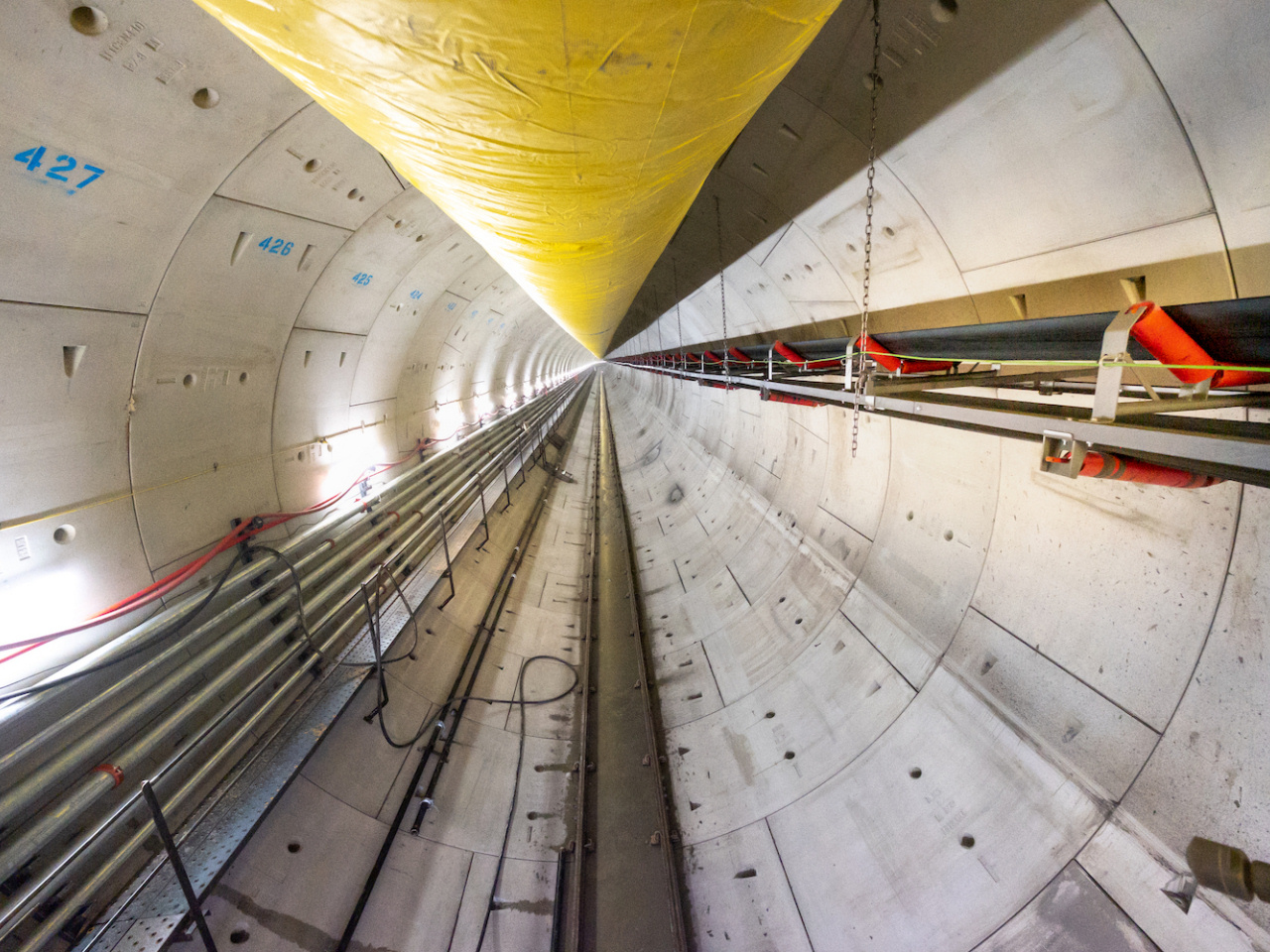

The solution is a brand new ‘Super Sewer’ (shown in the photo above) – the ‘Tideway Project’ – which will be over 15 miles long when completed, and, like Bazalgette’s, runs down alongside the Thames and in places, underneath it. It is far deeper – up to 90 feet below the ground or riverbed, and wide and tall enough for two double decker buses to drive through it side by side.

Although the construction is causing major disruption in parts of London, particularly to people who live by the river and close to the many sites where the tunnelling is taking place, there will eventually be an added benefit, similar to that of Bazalgette’s scheme – new public spaces along the bank of the river.

The enormous amount of waste material being excavated from the tunnel is being taken by barge some miles downriver to Rainham in Essex and used to create a nature reserve.

THE SAVOY

The Savoy Palace

The Count of Savoy was given land here in 1246 on which he built a magnificent palace. This later became the London residence of John of Gaunt, the uncle of Richard III, who was said to have been responsible for the implementation of the Poll Tax. This unpopular tax (history did of course repeat itself many years later) resulted in an uprising in 1381 that became known as the Peasants’ Revolt and which resulted in a mob led by Wat Tyler destroying his palace.

A hospital for the poor was afterwards built on the site, and it was later used as a prison and a military barracks. The semi-derelict buildings were demolished in 1820 in order to build Lancaster Place, the approach road to Waterloo Bridge. The Savoy Hotel was later built on the adjoining site.

The Savoy Hotel

The Savoy opened in 1889. It was built by Richard D’Oyly Carte, the founder and one-time proprietor of the Savoy Theatre which was already on part of the site (and, of course, still is). He had premiered eight of Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic operas in the theatre and they were so successful, particularly the Mikado, that he became so incredibly wealthy that he was able to build the hotel. (There’s a memorial to Richard in the garden in front of the hotel).

The Savoy was the first purpose-built luxury hotel in London, offering standards that had never previously been seen in any hotel in the world. It became the place to stay for the wealthy, famous, glamorous and notorious. Indeed, the list of notable people who have stayed there over the years reads like a ‘Who’s Who’ from the world of royalty, politics, business and entertainment – Edward VIII, Oscar Wilde, Barbara Streisand, Frank Sinatra, Charlie Chaplin, Jimi Hendrix and The Beatles to name just a few. And two famous guests didn’t just stay in the hotel – James Whistler and Claude Monet both painted the magnificent view of the River Thames from its windows.

One person who spent the last few years of his life in the hotel was the Irish actor and singer Richard Harris (he of the rather odd 1960 MacArthur Park chart hit). He was taken ill and just as he was being carried out of the hotel on a stretcher, he joked, “It was the food!” He died a few days later.

WATERLOO BRIDGE

The first bridge across the Thames at this point was built in Cornish granite by John Rennie and opened on the second anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo. It was to have been called the Strand Bridge, but, following the British victory over the French army at Waterloo, Parliament decided to rename it the Waterloo Bridge.

Consisting of nine arches, each with a span of 120 feet, it was described by the Italian architect Canova as the ‘Noblest bridge in the world’, who added that it was ‘worth travelling to England just to see the bridge.’

Unfortunately, the bridge had serious structural problems and after many arguments between conservationists, who loved the beautiful design of the old bridge, and users of the newly motorised vehicles who weren’t allowed to cross it because of its problems, a new bridge was eventually agreed upon.

The new bridge was built by the architect Giles Gilbert Scott, who was responsible for many other important buildings and structures in London, including the Bankside Power Station (now the Tate Modern) and the Battersea Power Station. He used Portland stone, which for many years had been popular for public buildings and other structures in London – one of its advantages was that the quarries from where it came were situated on the coast of Dorset and being adjacent to the sea meant that transporting it to London by barge was both economical and pre-20th century, relatively quick. Portland stone is also said to be ‘self-cleaning’ in rain. However, to ensure there’d be no further problems with stability, Scott also added beams of reinforced concrete, which proved to be difficult to implement.

The granite stones that were demolished from the original bridge were presented to various countries in the Commonwealth – two were used on a bridge in the Australian capital Canberra, whilst others were used for a memorial to a dog that used to roam the dockside in Wellington, New Zealand and which was popular with the local dockworkers.

As a result of a shortage of male workers due to it being war time, the bridge was constructed by a largely female workforce. Sadly, only a token handful were invited to the official opening ceremony.

TEMPLE BAR

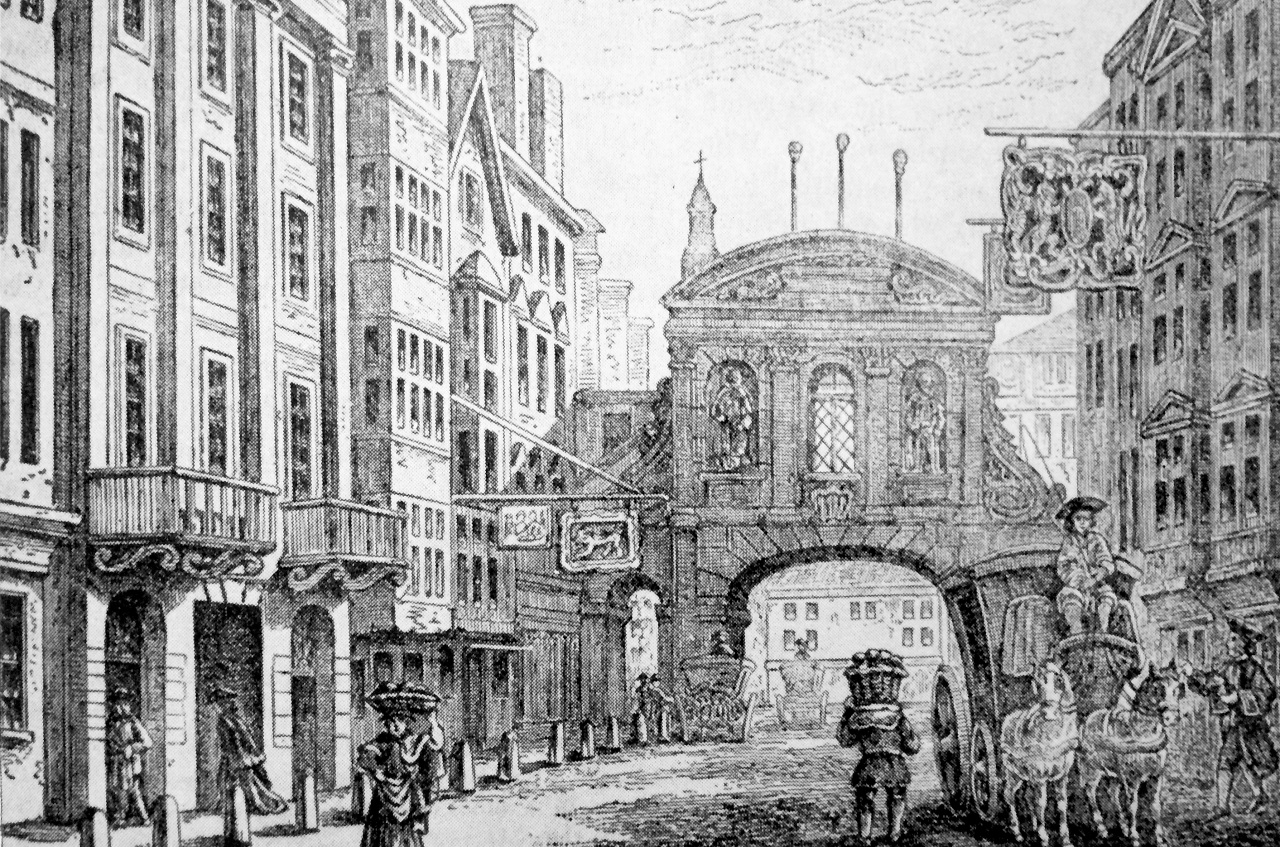

Temple Bar dates back to the 13th century, when it was a simple wooden bar fastened between two posts erected at the entrance to the City of London where people would pay tolls, particularly if they were bringing in goods.

A more elaborate wooden structure was built later, which even had a prison cell above it, as well as spikes on which the heads of those who’d fallen out of favour with the authorities were impaled. Although it avoided being destroyed in the Great Fire of London, it was in such a poor state that on the orders of Charles II it was rebuilt in Portland stone from the royal quarries in Dorset. Designed by Sir Christopher Wren, it had a central arch for carriages and a foot postern on either side.

In 1874 the structure was found to be unsafe as a result, it was thought, of the excavations for the building of the adjacent Law Courts. In addition, as the street had become busier, it was acting as a ‘pinch point’ and causing considerable delays to traffic. Consequently, the Corporation of London had the structure removed and the road widened. This had major implications for Child’s Bank, which I mention shortly, as not only did its premises adjoin the southern wall of the Temple Bar, but also because for many years it had rented the room above the gateway for the storage of its old records.

When Temple Bar was demolished, each individual stone was carefully taken down, its position in the structure labelled and the Corporation of London put it into storage. It was later purchased by Sir Henry Meux, the owner of the Horseshoe Brewery in London, to provide a grand entrance to his private estate in Hertfordshire.

A campaign was mounted a few years ago for the arch to be brought back to London and thanks to the Temple Bar Trust, private donations and the City of London Corporation, around £3 million was raised to have it re-erected adjacent to St Paul’s Cathedral.

More information can be found at www.thetemplebar.info.

THE OBELISK ON THE EMBANKMENT

The obelisk was one of a pair that was erected by Pharaoh Thotmes III around 1500 BC at the Temple of the Sun at Heliopolis. A third obelisk was erected some years later on the same site.

In 12 BC the obelisks were removed by Roman Emperor Caesar Augustus and taken to Alexandria, the Royal City of Cleopatra, where they remained until the Viceroy of Egypt presented one to Great Britain and one to America in the time of George IV. However, despite this kind gesture, the British Government didn’t think the obelisk was worth moving, but in 1877, the cost of doing so was underwritten by Sir Erasmus Wilson, a wealthy skin specialist and philanthropist. (He helped introduce the idea of Turkish Baths into Britain as well as campaigning for daily baths in the home – something quite revolutionary at the time!)

Weighing nearly 200 tons, it was encased in an iron cylinder and towed on its journey to London by a steamship. Unfortunately a severe storm blew up whilst it was being brought through the Bay of Biscay and it broke free. Six men were drowned in the storm, (their names are inscribed on the base of the obelisk) and at first it was thought to have sunk. However, fortunately it hadn’t, and the iron tube was spotted floating in the sea a few days later and the obelisk was eventually erected here in 1879.

The inscription on the obelisk reads; This obelisk, prostrate for centuries on the sands of Alexandria, was presented to the British nation in AD1819 by Mohammed Ali Viceroy of Egypt. A worthy memorial of our distinguished countrymen Nelson and Abercromby.

One of the other three obelisks went to America and now stands in New York’s Central Park, whilst the other went to Paris.

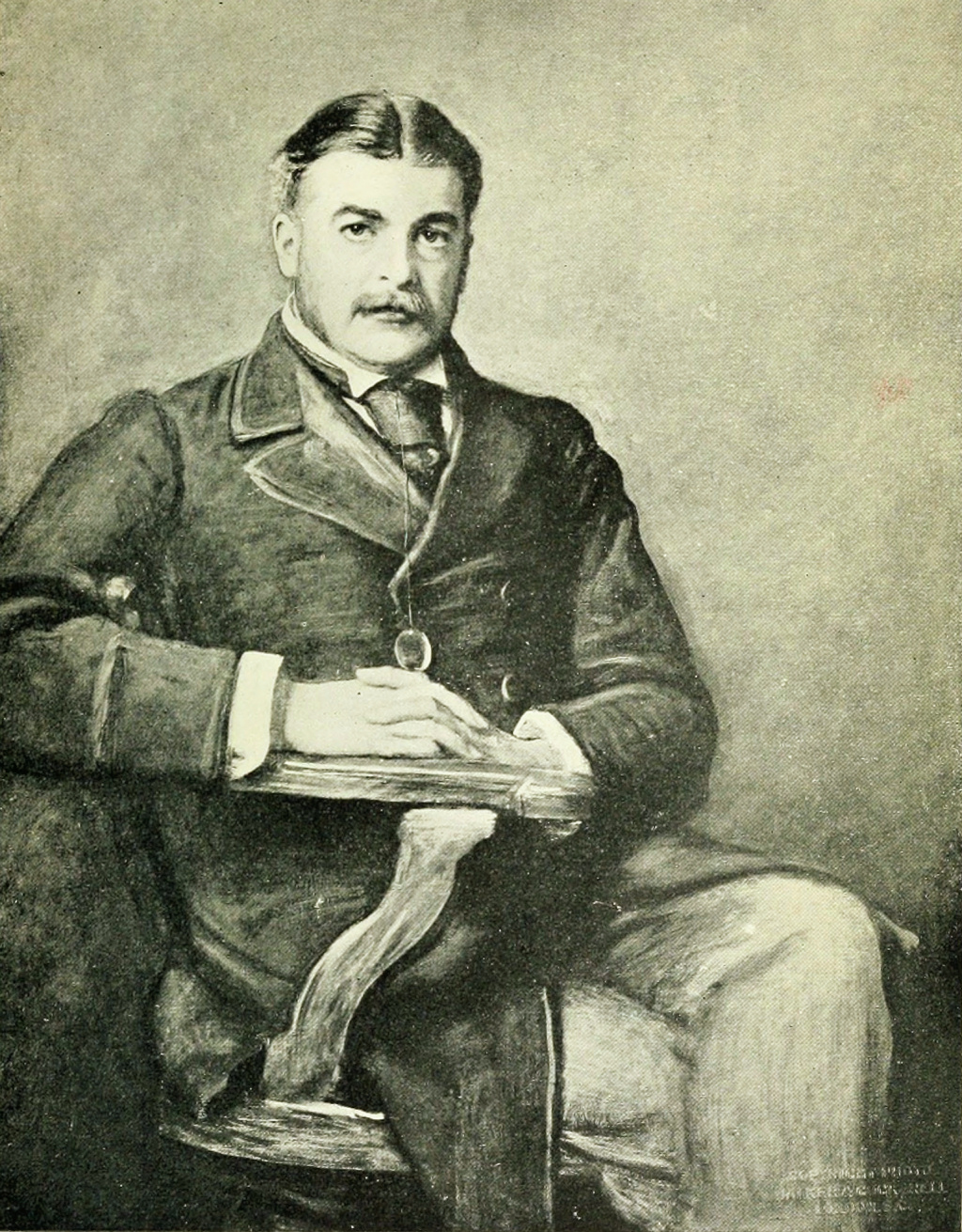

ARTHUR SULLIVAN

Arthur Sullivan was born just across the Thames in Lambeth and, as a result of his hugely successful career, was knighted by Queen Victoria when he was just 41 years old.

In total he wrote around 24 operas, eleven major orchestral works, eight choral works, two ballets and the incidental music to several plays. In addition to all of that, he composed various other musical pieces – chamber works, piano scores as well as a number of hymns, the most well-known being Onward Christian Soldiers. He also received commissions to write a number of essays.

I have read that Arthur always wanted to be known as much for his more serious choral works as for his ‘comic operas’, and it is said that he wrote the wonderful ‘The Lost Chord’ in this vein. It was written when his brother was dying, and Arthur was sitting by his bedside. It’s not at all well-known these days, which is rather a shame as it is a wonderful short piece of music. For anyone interested in listening to it, a famous version sung by Webster Booth and recorded in 1939 is available on YouTube.

Sullivan died of a heart failure following an attack of bronchitis when he was just 58, but his death caused something of a family problem because Queen Victoria overruled his wishes to be buried with the rest of his family in Brompton Cemetery, insisting that instead he was to be placed in St Paul’s Cathedral, which of course was what happened.

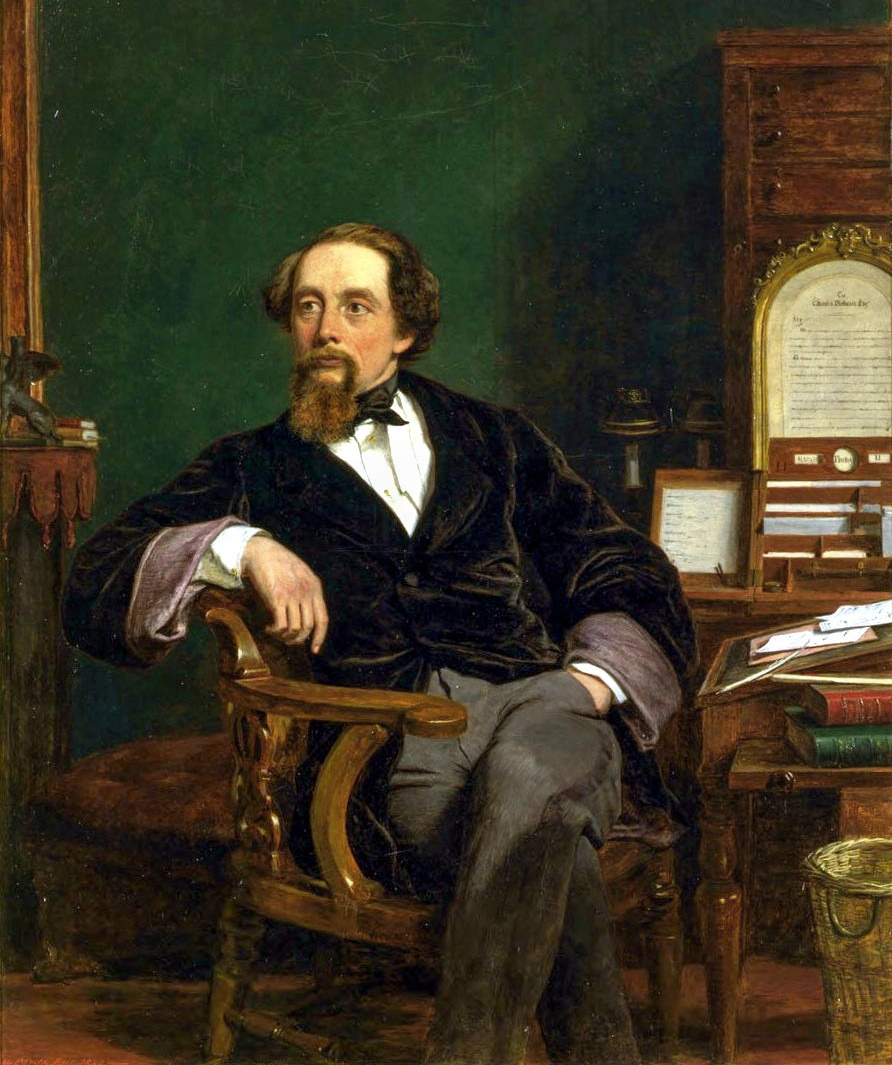

CHARLES DICKENS

We hear quite a bit about Charles Dickens on this walk. Indeed, right at the start, close to the Embankment station and the Hungerford Railway Bridge, was the site of the Warren’s Shoe Blacking Factory where the 12-year-old Dickens was forced to begin working. This was as a result of his father being put in the debtors’ prison, which meant his family suddenly became extremely poor. It was because Charles’s work in the factory was so boring that he first began to make up stories, initially just to amuse himself, but it wasn’t long before he was telling them to his fellow workers. And of course, some of these stories were to later make him so famous!

Apparently, the conditions in the factory were so awful that he never spoke of them again, though it is thought that he did make reference to some of those experiences in his book David Copperfield. Some say that it was a sort of autobiography, though he changed the name of the factory to Murdstone and Ginby.

Finally, not only did he work here, but his family lived in an attic room in the nearby Buckingham Street, though this has since been demolished.

SOMERSET HOUSE

A timeline history

I have taken this from the Somerset House website, where you’ll find much more information about the history and visiting this wonderful historic building.

1547 Edward Seymour, Lord Protector and Duke of Somerset, starts building a palace for himself on the banks of the Thames

1552 Seymour is executed at the Tower of London; ownership of his palace, nearly complete, passes to the Crown

1553 Aged 20, Princess Elizabeth moves to Somerset House; she lives there until 1558, when she’s crowned Queen Elizabeth I

1603 Anne of Denmark, wife of James I of England (James VI of Scotland), moves to Somerset House, which is renamed Denmark House in her honour

1604 The Treaty of London, ending the 19-year Anglo-Spanish War, is negotiated and signed at Denmark House

1609 Anne of Denmark invites Inigo Jones and other architects to redesign and rebuild parts of the palace; work continues until her death in 1619

1625 Charles I is crowned king; his wife, Henrietta Maria of France, commissions Jones and others to undertake more construction and renovation work, including a lavish new Roman Catholic chapel completed in 1636

1642 The English Civil War begins; soon afterwards, General Thomas Fairfax takes over the palace as the headquarters for the Parliamentary Army

1649 The Civil War ends, and Charles I is executed; Parliament tries and fails to sell Denmark House, but successfully sells its contents for the then-huge sum of £118,000

1652 Inigo Jones dies at Denmark House

1660 Charles II is crowned king at the start of the Restoration; Henrietta Maria, his mother, returns to Denmark House; more new construction follows

1665 The Plague sweeps through London; Henrietta Maria moves back to France, where she dies in 1669

1666 The Great Fire of London destroys much of the City of London, but stops just short of Denmark House

1685 Charles II dies and his wife, Catherine of Braganza, moves into Denmark House; Sir Christopher Wren oversees yet more construction and renovation work

1693 Catherine of Braganza leaves Denmark House, the last royal to live in the palace

early 1700s Denmark House is used as grace-and-favour apartments, offices, storage and stables

c.1750 Canaletto paints two views from the terrace

1775 After decades of neglect, the original Somerset House is demolished; architect William Chambers immediately starts work on its replacement

1779 The Royal Academy of Arts becomes the first resident of new Somerset House in what’s now known as the North Wing

1780 The Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries take up residence in the North Wing; Somerset House hosts the first Royal Academy Exhibition

1786 The Embankment Building, known today as the South Wing, is completed; the East and West Wings are completed two years later

1789 The Navy Board completes its move to Somerset House and eventually occupies one-third of the site; the Stamp Office, responsible for taxing newspapers and other documents, joins the board in the South Wing

1795 William Chambers, then aged 72, retires; James Watt replaces him as the building’s architect

1801 The new Somerset House is deemed complete; its construction having cost a mammoth £462,323

1829 Sir Robert Smirke starts work on King’s College, which opens in 1831 and is finally completed in 1835

1836 The General Register Office, responsible for births, deaths and marriages, is established here

1837 One year after the final Royal Academy Exhibition at Somerset House, the academy moves to Burlington House on Piccadilly

1849 Having merged in 1834, the Stamp Office and the Board of Taxes join with the Board of Excise to form the Inland Revenue, which remains in residence for more than 150 years

1856 Seven years after James Pennethorne started work on its design, the New Wing is completed

1857 The Royal Society moves out of Somerset House to join the Royal Academy of Arts at Burlington House; the Society of Antiquaries follows 17 years later

1864 Work begins on the Victoria Embankment, designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette; the embankment is completed in 1870

1873 The Admiralty leaves Somerset House; its offices are taken over by the Inland Revenue

1940s Near the start of World War II, the Inland Revenue temporarily moves out of Somerset House; the Ministry of Supply takes its place

1950 Sir Alfred Richardson starts a two-year project to rebuild the Navy Staircase, known today as the Nelson Stair, which had suffered terrible bomb damage in 1940

1970 After 134 years at Somerset House, the General Register Office moves out

1989 The Courtauld Institute of Art moves into the North Wing

1997 The Somerset House Trust is established to preserve and develop Somerset House for public use

2000 The River Terrace opens to the public for the first time in more than a century; the Hermitage Rooms and the Gilbert Collection both open; then, in December, Somerset House installs a temporary ice rink for the first time

2001 American band Lambchop plays the first gig in the Edmond J. Safra Fountain Court; a full programme of shows follows in 2002 and continues today as the Summer Series

2009 London Fashion Week takes place at Somerset House for the first time

2011 The HMRC (formerly the Inland Revenue) closes its offices at Somerset House

2016 Somerset House Studios launches

CHILD & CO.

Until its recent closure, this was the oldest bank still trading in the United Kingdom and evolved from the goldsmithing business of Robert Blanchard, who was joined in 1665 by Francis Child. They were among a small group of goldsmiths who, in the late 17th century, revolutionised personal finance. By offering banking services and developing new forms of paper money, they significantly helped reduce the risks and difficulties involved in undertaking financial transactions (see the subsection below).

The original offices, which were described by the Daily Telegraph as the ‘grimy banking house of Messrs Child and dingy in aspect’ were attached to the Temple Bar and so jutted out into Fleet Street. This increasingly caused congestion, so it must have been a relief when Child’s agreed to surrender part of their land to erect a new building that was set further back, which is the one we see today. This widening of Fleet Street must also have benefitted the firm as previously the carriages of visiting clients would sometimes completely block the thoroughfare.

Child’s Bank was believed to have been the model for Tellson’s Bank in Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. In it he wrote, “Tellson’s Bank by Temple Bar was an old-fashioned place … It was very small, very dark, very ugly, very incommodious … a miserable little shop, with two little counters, where the oldest of men made your cheque shake as if the wind rustled it, while they examined the signature by the dingiest of windows, which were always under a shower-bath of mud from Fleet Street, and which were made dingier by their own iron bars proper, and the heavy shadow of Temple Bar’.

The building we see today was designed by the eminent architect John Gibson and built with a Portland stone frontage, high-arched ground floor windows and embedded columns like giant pillars that rise through the second and third storeys. With a first-floor balcony and an overhanging cornice it was certainly an impressive building, and not surprisingly now Grade II listed.

At the rear of the building were the living quarters of the servants, whilst on the upper floors were the sitting rooms and bedrooms of the members of staff who lived in. Telephones were installed in 1893 and electric lighting in 1899 – both very advanced at that time. The building was modernised again in 2015 and Child’s is now the private banking division of the Royal Bank of Scotland.

Child & Co. and the early years of banking

I mention in the walk how Child & Co. changed from being goldsmiths to being bankers and for those interested I’ve written a little more about the early days of banking.

The first banknotes – In the mid-17th century, goldsmiths already used to manufacture and dealing in items of high worth, also began to accept their client’s’ valuables and money for safe keeping. In return, they issued receipts, effectively promises to return the items or pay the value on demand. It was these receipts which developed into transferrable promissory notes that became the forerunners of the modern banknote.

The first cheques – Blanchard and Child began accepting written instructions from their clients to make payments to third parties. Called ‘drawn notes’, because they drew on the customer’s funds held by the goldsmiths, these handwritten requests often began with the words ‘Pray pay’ … followed by the name of the recipient, and the amount to be paid. The drawn note was the predecessor of the modern cheque, whose wording was standardised in the 18th century when the bank issued its first cheques.

The first bank accounts – Blanchard and Child recorded each customer’s transactions in a dedicated account in the bank’s ledgers, with payments on one side and receipts on the other – these ledger entries were precursors of our modern bank accounts. They also used ledgers to record loans to clients, which they referred to as ‘pawnes’, reflecting the fact that the loans were made on the security of the valuables their clients deposited.

Some of this information was taken from a brochure published by Child & Co. giving brief details of the company’s history.

ST DUNSTAN-IN-THE-WEST

Legend says that the first church here was built by the British King Cadwallon (and no, I haven’t either!) in the 7th century, around the time of the first St Paul’s. A new church was built here in Norman times, which was rebuilt in 1437, and named St Martin, after a Roman soldier who converted to Christianity in northern France.

The Native American princess Pocahontas is said to have visited the church when she lived on Ludgate Hill in 1616 and was befriended by the rector.

Admiral Sir William Penn the naval reformer and father of the founder of Pennsylvania was married here in 1643.

The first church on the site was built around 990AD, and was saved from the Great Fire in 1666 thanks to a sudden change of wind and forty scholars of Westminster School who, whilst the fire raged around them, formed a line to manhandle buckets and managed to put out the blazing nearby buildings. The clock on the front of the church was a gift from parishioners to give thanks to God for the timely change in wind direction.

The church we see today was built in the 1830s when it was moved back to allow Fleet Street to be widened. Because the site was then a lot smaller, the problem of lack of space was solved by designing the church’s interior in an octagonal shape. Although its tower was badly damaged by bombs in the Second World War, it was rebuilt in the 1950s thanks to the generosity of a newspaper magnate.

As with St Bride’s, which we see shortly, its churchyard was used by many booksellers (I explain why then). Here was published Hamlet and Romeo & Juliet, Izaak Walton’s Compleat Angler and a poem by a blind poet by the name of John Milton called Paradise Lost.

The clock of the previous church was one of London’s top sights and the ‘giants’ that struck the hours were put in place as far back as 1671. It was said that the two figures were “more admired on Sundays by the populace than the most eloquent preacher in the pulpit within.” I like the fact that Lord Hertford, who used to see them as a child when he visited in 1708, said that one day he’d buy them. He did … and set them up at his house in Regent’s Park. However, when the church was being rebuilt in the 19th century, they were returned here by Viscount Northcliffe to mark the Silver Jubilee of George V.

Above the parochial school in the courtyard are statues of King Lud, the mythical sovereign, and his sons, as well as Elizabeth I, which all once stood in Ludgate. There is also a memorial to Lord Northcliffe, founder of the Daily Mail and Daily Mirror.

St Dunstan’s is unusual in being both an Anglican and Romanian Orthodox Church as well as having links with Armenian, Coptic, Syrian, Ethiopian, Lutheran and the Reformed Church – truly very ecumenical! And the reason it’s called St Dunstan-in-the-West is to distinguish it from another church of the same name in the east of London.

SERJEANTS’ INN

Serjeants’ Inn takes its name from its previous premises at 50 Fleet Street, one of the City of London’s important historic sites. It is said that during the 16th and 17th centuries the Inn formed the legal centre of England. The freehold of the Inn was given to the Deans and Chapter of York and Canterbury in 1409 and they held it until 1838 when it was sold to the Amicable Society to relieve financial difficulties caused by a calamitous fire in York Minster.

In 1516 the judges and Serjeants commenced their long occupation. The “Serjeants” were a “superior order of barristers” from among whom Common Law Judges were chosen. On 4th September 1666 the inn was completely destroyed by the Great Fire of London.

Subsequently, John Hartley, a book seller in Fleet Street, formed the very first life insurance office, the Amicable Society, in 1706, and the society purchased 50 Fleet Street for occupation in 1838. In 1866 the Amicable Society was amalgamated with the Norwich Union Life Insurance Society and in 1881 the society’s freehold interest in the inn was sold. In 1954 Norwich Union repurchased the site and rebuilt the inn in its present form after it had been gutted by incendiary bombs in 1941.

In 1912 the former Amicable premises at 50 Fleet Street were affected by road widening and as a result the society purchased nos. 48, 49 and 51 Fleet Street. The gates of the building were removed during rebuilding works and then lost for many years until they were discovered in a scrap yard in 1937. They were then taken to Norwich and built into an extension to the Norwich Union head office before being returned to Fleet Street in 1959, where they were initially sited in the wrong place until 1970, when they were sited in their present position.

In 1986 the barristers’ chambers in Carpmael Building, Temple, relocated to 49 Fleet Street and became Number 3 Serjeants’ Inn Chambers – the first common law set of chambers to move out of the Inns of Court and into commercial accommodation. In 2013 Serjeants’ Inn Chambers moved out and the building was totally renovated to become the five-star Apex Temple Court Hotel.

FLEET STREET AND NEWSPAPERS

Fleet Street has been synonymous with the printing and newspaper industry for several hundred years. In the alleys, courts and lanes off Fleet Street there had been considerable printing activity for hundreds of years. Small printing offices produced everything from broadsheets to bibles. On the upper floors skilled compositors arranged the type ready for the pressmen downstairs, who undertook the inking and printing. Allied trades such as engraving and bookbinding were located nearby.

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, newspapers with limited local distribution began to be produced in the Fleet Street area. The first daily newspaper to be published there was the Daily Courant, soon joined by renowned titles such as the Daily Universal Register (1785), which was renamed The Times, and The Observer (1791). In 1814, John Walter II increased the speed of printing newspapers by introducing steam-driven cylinder presses at The Times, whilst the repeal of the stamp duty (which I mention elsewhere) in 1855 were both major turning points for the industry.

Fleet Street, lying conveniently between the key financial and political areas of London, soon became the centre of newspaper and periodical publishing. Many new mass-market titles, some costing as little as a penny, were launched from here. The electric telegraph made home and foreign news-gathering faster and more efficient. Distribution was improved by the growing railway network.

1890s–1920s

The 1890s saw the emergence of popular magazines and newspapers aimed at a new and much larger market. The target reader was the ‘ordinary person’. Alfred Harmsworth’s Daily Mail, first published in 1896, was the most successful of these new popular newspapers. It featured bold headlines, lively journalism and many illustrations. Harmsworth, later Lord Northcliffe, exploited the latest printing and news-gathering technologies; the linotype typesetting machine, typewriter and electric telegraph. He launched the tabloid Daily Mirror in 1903, and in 1908 he bought out and quickly revived The Times, becoming Fleet Street’s first newspaper tycoon.

By the first decades of the 20th century, Fleet Street had become the centre of Britain’s national newspapers, as well as a centre of world media, rivalling New York. It became the aspiration of young journalists to work there.

The End of ‘Ink Street’

During the first half of the 20th century, newspaper readership levels and advertising revenue grew steadily. By 1947, the Daily Express and the Daily Mirror both had a circulation of nearly four million. Concentrated in and around Fleet Street were the buildings of the major national newspapers. In addition there were many news and photo agencies and all the offices of the many specialist, provincial and foreign magazines and newspapers.

The introduction of new electronic printing technology in the 1980s, which made the skills of many print workers obsolete, brought already uneasy relations between managers, unions and print workers to a crisis point. It was Murdoch’s frustration with the unions that finally prompted the move of his four newspapers out of Fleet Street and into a purpose-built plant at Wapping, nicknamed ‘Fortress Wapping’ that became the scene of many angry battles. Other newspapers followed, not only because of problems with industrial relations, but also because many had outgrown their cramped and expensive sites, swapping them for cheaper locations elsewhere in London. With the departure of newspaper printing from Fleet Street in the 1980s, central London lost its last great manufacturing industry. Developers moved in to create prime office space – Fleet Street had entered a new era.

Some of the information for this has come from an excellent exhibition about Fleet Street and the newspaper industry in the crypt of St Bride’s Church – and designed and produced by the Museum of London.

ST BRIDE

The first religious building on the site was thought to have been erected by the Romans in AD43 so it is one of the earliest known sites of worship in Britain. The first Christian church was built here in the 7th century and thought to have been founded by St Bride or St Bridget of Kildare. She was the daughter of a 5th century Irish prince, who became a Christian and wanted to devote her life to her calling, but her father was against this. However, it was said that after she had given away much of his wealth to the poor, he realised she was clearly very serious about it and subsequently agreed with her wishes. She entered the monastery at Kildare and became the abbess. She was known to have travelled widely, presumably including London.

The church we see today is the seventh to have been built on this site and replaces a Norman church that was built in the 11th century and destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. The diarist Samuel Pepys, who had been baptised in in the church in 1633, witnessed the church being destroyed in the fire and wrote about it in his diary.

The church was rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren, reopening in 1675, though the steeple wasn’t finished until some years later. Indeed, it is the spectacular steeple – said to have been the most beautiful that Wren designed – which is one of the reasons that the church became so famous.

For many years it was one of the tallest churches in London, though the steeple did lose around eight feet of its height after being struck by lightning in the 18th century. It’s just over 230 feet high and consists of four ‘tiers’, each reducing in size as it ascends. And it is this unusual design which has resulted in the steeple’s significant role in weddings, or at least in the tradition of the cake – the tiered wedding cakes, which are served at most receptions, are said to have been the invented by an 18th century pastry maker who lived nearby on Ludgate Hill. He created a cake inspired by the tiered steeple for his own marriage – and it’s a tradition that has carried on ever since.

Despite the intense bombing in the Second World War that devastated so much of the City of London, the steeple survived – although the church didn’t, being hit by firebombs which resulted in much of it being destroyed. Fortunately the church’s long-standing relationship with the many newspapers based in Fleet Street resulted in them giving significant amounts of money to help with the rebuilding. (As you may have noticed when you walked into the church, the sign at the entrance proudly says it’s the ‘Cathedral of Fleet Street’ and even though newspapers have long since moved out of the street, it has retained a close relationship with the publishing industry).

FLEET STREET AND THE PRINTING INDUSTRY

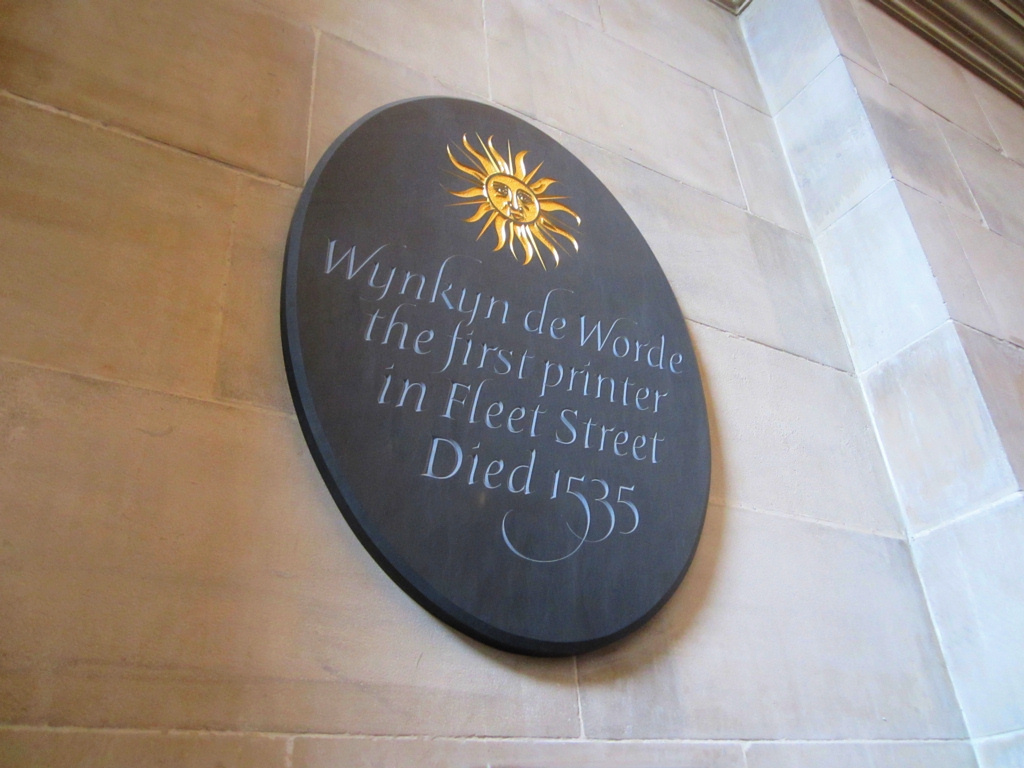

Fleet Street’s association with printing began around 1500 when Wynkyn de Worde set up his business in the St Bride’s churchyard (he was later buried here). He had been an apprentice and friend of William Caxton, who is regarded as being the ‘father of printing in England’ as he was the first to introduce printing into Britain, which he did in his printing workshop in Westminster.

People sometimes wonder why churchyards, like that of St Bride’s, were popular with the early printers. St Bride’s, like St Dunstan’s that we saw earlier, would have been places where lawyers would meet to seek business and it was where clergy and other learned scholars would also gather. St Bride’s was situated in an area known for its religious connections and it was around here that a number of eminent churchmen such as the Bishops of Salisbury, Peterborough and Ely lived – and their names are remembered in several of the nearby squares and courtyards.

They would have been amongst the few people who could read in those days and as a result, potential customers for early printed books. Therefore it was a logical place for Wynkyn to set up the press he had purchased from Caxton. Indeed, over the years the list of literary people who have lived within the parish of St Bride’s reads like a who’s who of great writers – Dryden, Izaak Walton (best known today for his Compleat Angler), John Aubrey, Samuel Pepys, who along with his eight brothers and sisters was christened within the church, Milton, Hogarth, Pope, Boswell, Johnson, … whilst the likes of Wordsworth, Keats, Thomas Hood and William Hazlitt ‘held levees in a local coffee house’. (And if you don’t know what a levee is, neither did I, but according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, it means a ‘reception held by a person of distinction on rising from bed’- other meanings are a reception usually in honour of a particular person.

For those interested in learning more about Wynkyn de Worde, (and I can’t help but think what a great name he had for a printer) then I suggest you take a look at this excellent website: www.intriguing-history.com.

Finally, the relationship between church and printers – Since the 15th century St Bride’s has been known as the ‘printer’s church’ – and over more recent times the church of journalists and writers as well. The relationship between church and print is unique. Just one example is that those in the printing industry have always called their union branches ‘chapels’, whilst the head of each ‘chapel’ is known as Father – who in a different industry would be known as the ‘shop steward’.

PATERNOSTER SQUARE

Firstly, the meaning of the word ‘Paternoster’* … it comes from two Latin words – Pater and Noster, which mean ‘Our Father’, the first two words of the Lord’s Prayer. ‘Paternoster’ has become another name for the strings of prayer beads – more commonly known as rosary beads – that are used by Catholics. The priests of St Paul’s (of course it was then a Catholic cathedral) would walk along this street reciting the ‘Paternoster’ whilst holding their rosary beads and in the 14th and 15th centuries there were many makers of the beads living here.

Until the Great Fire of London in 1666, much of Paternoster Row was occupied by the stalls and shops of mercers, (merchants and traders who would sell silks, linen, furs and general textiles). In addition, this area around St Paul’s Churchyard increasingly became the home of many printing and publishing companies as well as booksellers. Indeed, the magnificent Hall of the Stationers’ Livery Company, who for several centuries were the official organisation that regulated printing and publishing, is just around the corner. Until as late as 1911, all new books had to be registered at Stationers’ Hall. (I explain in the walk how you can see the hall).

Unfortunately, much of Paternoster Row and the surrounding area was destroyed in December 1940 during one of the heaviest attacks that London received and the medieval streets and the wonderful old buildings housing those booksellers and publishing companies were destroyed. In addition, several million valuable books and manuscripts were also lost in the fire that night.

Rebuilding work on the area began in the 1960s but, as with so much of the redevelopment of the bomb-damaged cities of Britain at that time, what was built in its place was regarded by many as being ‘poorly designed and ugly’. Indeed, it was described by Robert Finch, the Lord Mayor of London in an article in the Guardian newspaper in 2004 as being made up of “ghastly, monolithic constructions without definition or character”.

Fortunately, further redevelopment has taken place quite recently and, as a result of significant investment by the Japanese Mitsubishi Development Company, the modern and considerably more appealing Paternoster Square you see today opened in 2003, (though I accept that being so modern may not be to everybody’s taste).

* As an aside, Paternoster is also the name given for lifts that go around on a loop – i.e. travel up one side and back down the other. As they are now rarely seen due to safety concerns, I doubt many people have ever seen one, let along get in one. However, I do remember them as there used to be one in the Co-op department store in Bristol. And the reason they were called ‘Paternoster Lifts’ – simply because they go around in an endless loop, like rosary beads.

ST PAUL’S CATHEDRAL

- It’s built on Ludgate Hill, the highest point in the City of London

- This is the fourth cathedral to have been built on this site, the first being in AD604. It was built in wood and destroyed by fire in 1087. Whilst it’s hard to comprehend, the third was built by the Normans, and was actually even bigger than St Paul’s we see today. Unfortunately, it was destroyed during the Great Fire of London in 1666.

- The task of its rebuilding was given to the architect Sir Christopher Wren; he was 43 years old when the foundation stone was laid in 1675 and the final stone was said to have been put in place by his son, 35 years later, when Wren was seventy-eight years old.

- Many people, and certainly including myself, have wondered how he managed to rebuild so many churches following the Great Fire – you see his work all over the City – but I understand that although he was said to have visited the site every week, the day to day responsibility for the cathedral’s rebuilding was the responsibility of Thomas Strong, a Cotswold master builder.

- One of the cathedral’s spectacular architectural features is its magnificent dome. It rises 365 feet to the cross on its top and has a diameter of 102 feet. It is the next largest to the dome of the Basilica of St Peter’s in Rome, from which Wren was said to have drawn inspiration. It is comprised of three ‘shells’ – the outer dome; a dome constructed of brick which acts as the support and a painted inner dome (the painting is of the life and work of St Paul).

- As a result of the dome’s design and shape, sound carries across to the Whispering Gallery, which runs around it. At its top is the ‘Golden Gallery’, which is open to visitors, though be aware that it’s a climb of 257 steps to reach the Whispering Gallery and a further 271 steps to the Golden Gallery – a total of around 520.

- The crypt, said to be the largest of any religious building in Western Europe and runs the full length of the building, is also open to visitors.

- Having a funeral, burial or memorial here is something only granted to those held in the highest esteem by the nation and includes such varied luminaries as the cathedral’s own architect, Sir Christopher Wren, who died at the age of over 90 – quite an astonishing age for that era – and I do like the inscription that’s written in Latin on his tomb which quite simply says ‘ … if you seek his memorial, look around you’. Others include Florence Nightingale, Admiral Lord Nelson, William Blake, John Donne, Canaletto, Sir Alexander Fleming, Winston Churchill and Maggie Thatcher.

- St Paul’s was the tallest building in central London until the BT Tower was built just off Tottenham Court Road in 1961–5.

- The cathedral has a number of bells. Two of the best-known are Great Tom and Great Paul. Great Tom is rung when there is a death of a member of the royal family, a Mayor of the City of London, The Archbishop of Canterbury or the Bishop of London. Sadly, I understand Great Paul, which weighs over 16 tons and the largest ever cast in Britain, is currently awaiting repair. The twelve ‘ringing bells’ form the second largest ‘ring’ in the world. Other bells are rung on different occasions, such as before a communion service begins.

- St Paul’s has held the thanksgiving services for the Silver, Golden and Diamond Jubilees of Queen Elizabeth II, as well as her 80th and 90th birthdays. It was also where the wedding service of Prince Charles and Lady Di was held.

- St Paul’s is a ‘working church’ and services of worship are held several times each day – information is provided on the St Paul’s website.

More information

It may sound strange to suggest, but for more information on St Paul’s I recommend the children’s website Kiddle – it’s extremely well written and helpful.

Visitor information

The cathedral is open to visitors from Monday through to Saturday (it is only open for worship on Sundays) between 8.30am and 4.30pm – the last admission is at 4.15. Bear in mind though that it is recommended that a visit will normally take between one and two hours.

Current admission prices are £20 for adults, £17.50 for concessions (students and over 60s) and £8.50 for children aged 6–17. (Family tickets are also available).

There are also several organised guided tours each day. For more information please see the cathedral’s website.