Updated: 11 June 2019 |

|

Walk page: Click to view |

Appendix to the City of London walk 2

MORE ABOUT THE CITY OF LONDON

As this walk takes place in the City of London, I have begun this appendix with some background and history on the City. I have then written more specific background to some of the City’s unique institutions – for example the livery companies and the wards and watch system.

Following this, I continue with my standard format, giving further details about various specific places, events or people that we encounter during the walk for those who’d like more information.

Firstly, a brief overview

The City of London is sometimes said to be unique. It’s a city within a city, and a county as well (though not a country as the Vatican is). Indeed, I have actually heard the City of London being referred to as the ‘Vatican of the Commercial World’.

Rather uniquely, it is technically not subject to the Crown – nor to Parliament, where it even has its own special ‘representative’ called the Remembrancer. He or she sits close to the Speaker of the House – and has a similar seat in the House of Lords. They are the only non-MP or civil servant with a seat in Parliament and their job is to ensure that the City’s unique rights are maintained, a role that dates back to the time of Henry VIII when the City of London felt he was interfering with their affairs. In practice they do more than that, acting as a channel of communication between the City, Parliament and the Crown.

As a result of not being technically subject to the Crown, the City is the only part of the United Kingdom where the Queen has to ask for permission to enter. When she visits, she’s met by the Lord Mayor at Temple Bar, (where the Strand becomes Fleet Street), makes a little bow and asks for permission to enter. The Mayor then in turn hands her the City’s Sword of State, which signifies an invitation to enter.

The City is small, measuring just under 1 ¼ acres, yet its influence has for centuries extended across the world – and in financial matters still does. Indeed, until the start of the 20th century it was regarded as being the world’s centre of finance, insurance and trade. It is also the country’s centre for the legal profession. Much of the wealth of Britain is created and generated through and by the businesses based in the City of London, which has always been known as Britain’s principle financial and business centre. And despite the growth of financial industries in places like New York and Hong Kong, it is still one of the world’s leading centres. Although over the past twenty years some of the City’s financial service industry has moved a couple of miles east to Canary Wharf, the City itself still dominates.

The ‘Square Mile’

The map here shows what a compact area it is. And as a matter of interest I’ll mention here that the entrance to the City is marked at the boundary on most roads leading into it by a cast iron ‘dragon’ mounted on a stone or metal plinth. Most are painted silver, with their wings and tongues in red. Examples can be seen at Victoria Embankment, Temple Bar, Holborn, Farringdon, Aldersgate, Moorgate, Bishopsgate, Aldgate, London Bridge and Blackfriars Bridge.

A very brief history of the City of London

I emphasise that this is just my personal interpretation of a very complex story

It’s really a ‘Tale of Two Cities’ and I’ll begin by mentioning that whilst most cities have a cathedral – London is made up of two cities and therefore has two cathedrals. The City of London has St Paul’s Cathedral (visible on the left of Daniel Turner’s painting, c.1790), whilst the other is the City of Westminster, which has as its cathedral Westminster Abbey. That’s the first of many ‘oddities’ about London.

Visitors to London – particularly those from overseas – often get confused with the concept of the ‘two Londons’. There’s the London of Buckingham Palace, the Royal Parks, Oxford Street shops, the West End’s theatres, Covent Garden’s bars and restaurants, Westminster Cathedral and the Houses of Parliament – and then when they look at a map, they can see a small one-mile square area called the ‘City of London’, a ‘city within a city’ that’s famous for being a centre of international finance and banking, a place of ancient customs, towering skyscrapers and historic buildings. Then they discover it has its own police force, a mayor who is a ‘Lord Mayor’ and appointed not in any real democratic way, but by a small number of influential and successful businessmen within the City, completely unlike Sadiq Kahn or Boris Johnson, who are elected by the population at large. And even more strangely, whereas the ‘metropolis’ of London has a population of over eight million, the City of London’s is just a tiny resident population of just seven thousand (in the last census of 2011 – current estimates are that it is now nearer to eleven thousand).

And of course besides all of that, it’s a place where even the King or Queen must stop at its boundary to ask permission from the Lord Mayor to enter …

No wonder visitors can get confused!

And all of this is precisely the reason why I love the City and find walking around it so fascinating.

The City was extensively bombed during the Second World War, which caused widespread damage to many of its historic buildings, (and of course we mustn’t forget that much of it had previously been destroyed four hundred years earlier in the Great Fire of 1666) it is still a place of fascinating customs; historic quirky buildings, little ancient alleyways and squares, beautiful churches … and between my two walks – City Walk One and City Walk Two, we see many of these places.

The City of London is one of Britain’s most historic areas. For the past 2,000 years it has been the centre of commerce and trade in Britain – and in the 19th and 20th centuries, much of the world.

The City of London is often referred to as the ‘Square Mile’, which indeed it almost is; despite its fame and achievements it is just a very small area. It’s the oldest part of London and dates back to Roman times. There were probably settlements going back even earlier, but it was the Romans who first built a ‘city’ here.

Indeed, its size hasn’t really changed much since those Roman times. They settled here in AD50, some seven years after they had invaded Britain, creating a city known then as Londinium. They had chosen this particular site to build their settlement as at this point the River Thames narrowed sufficiently to enable them to build a bridge, allowing a connection to be made with their crossing points between Kent and the continent.

The city grew until some ten or so years later (around AD60) it was attacked by Boadicea, the Queen of the Iceni tribes who lived in an area of what today probably includes much of Cambridgeshire, Suffolk and Norfolk. She attacked and burnt down Colchester, which was then the Roman capital of Britain, before heading south to destroy Londinium, indiscriminately killing most of the population – locals and Romans alike.

However, displaying the efficiency for which they had become famous, within ten years the Romans had rebuilt the city, larger and more prestigious than it had been before, and made it their capital. In order to protect it, both from British and foreign invaders, they established the boundaries of the city and began building an enormous stone wall around them.

The wall was a mighty undertaking. London is built on clay, not rock, so the stone for its construction had to come from elsewhere, and they chose a ‘ragstone’ from Maidstone in Kent. Once quarried, this had to be brought by barge around the coast of Kent and up the Thames, in itself a monumental feat, as it is estimated that well over a thousand barge loads would have been needed, as the wall was around 15 – 20 feet high and around 7 or 8 feet thick.

This great defensive wall, much of which wasn’t built to its eventual height and width until almost AD180-190, has played an enormous role in both the success and preservation of the uniqueness of London, making it such a fascinating place to explore.

The Roman wall had generally followed the line of existing defences, and incorporated the same gated entrances to the City, with more being added over time. Until at least the 15th century these gates were guarded at all times and locked at night. (The position of some of those gates are recognised today by street names or districts – Newgate, Aldgate, Bishopsgate, Ludgate for example).

Much of the wall has been demolished over time and the stone used in houses and other buildings, but parts of it can still be seen today – for example in the underpass between Tower Hill Tube Station and the Tower of London, or in nearby Coopers Row, at the rear of the ‘driveway’ entrance adjacent to the Grange City Hotel. The street called ‘London Wall’ follows the route of the wall westerly for just over ¼ of a mile, though you see little evidence of it. However, there is a particularly good example of it in Noble Street, that’s close to the Museum of London and which we walk along in the City of London walk 1.

Defensive walls were also built along the riverside, and again gates were built into it to provide access to the Thames.

Although London had become such an extremely prosperous and prestigious Roman city, with grand public buildings, an enormous amphitheatre and the largest basilica this side of the Alps, all ‘good’ things come to an end, and by the beginning of the 5th century the Roman Empire was in rapid decline. Rome itself was becoming under threat from invaders from the east of its empire, and with London being its most northerly outpost, its soldiers were withdrawn to help to protect it.

As a result, within less than a hundred years, what had seemingly become a quite magnificent city became virtually abandoned – something I find hard to understand and imagine.

Saxon times

The next 600 years or so, sometimes referred to as the ‘Dark Ages’, saw the Saxon invaders moving into southern England. By the 5th and early 6th century the Anglo Saxons had begun settling just outside the old Roman city (why they didn’t just move into the city the Romans had built and left, I’ve never understood). They are believed to have made a base somewhere just slightly north of today’s Strand/Fleet Street, which they called Lundenwic. (The Anglo-Saxon word ‘wic’ meant ‘trading town’, so it was ‘London trading town’.) They based themselves here and built a small harbour as it was adjacent to where the River Fleet entered the Thames.

By the 9th century, the Vikings from Denmark had begun raiding England, particularly on the eastern side of the country, though eventually being defeated by the Saxon King Alfred the Great, who then set about strengthening and in places rebuilding the old Roman fortifications to be strengthened and in places rebuilt.

The Danes (rather than the Vikings) began attacking in the 10th and early 11th century and eventually, in 1016, Prince Cnut the Great (later known as Canute), the son of the Danish King, successfully invaded and became King of England.

By 1100 the population of London was said to be around 15,000 and within two hundred years it had increased to 80,000.

William the Conqueror and the Norman invasion

The Norman invasion in the 1060s saw William the Conqueror’s quickly realising the importance of London and he began to redevelop the City, reinforcing the defensive walls that the Romans had built a thousand years before. To make the City of London even more secure, he set about building the Tower of London; its massive size was designed to as much to intimidate and subdue the local population and so prevent any uprising as it was to deter any possible foreign invaders.

In addition, William quickly realised that granting rights and privileges to the City of London, in return for them acknowledging him as King (and paying taxes), made a lot of sense. As subsequent royals have also realised. It is said that since then there’s been a thousand-year history of monarchs allowing the City of London to carry on doing what it does best, which is to make money and pay taxes, whilst at the same time distrusting it.

By the beginning of the 12th century, the City of London was granted an important new charter, another step towards its ‘self-government’. This included the ability of the City to appoint their own Sheriffs, allow citizens to be tried in their own courts, reduce the taxes the citizens had to pay to the Crown and much more.

The population of London continued to grow, though the ‘Black Death’ plague in the mid-14th century saw the City lose around half of its population. but as a result of the City of London’s political and economic importance – and despite further epidemics – the population continued to rise quite rapidly.

Another major upheaval that had considerable effect on London took place in the middle of the 16th century, when King Henry VIII broke away from the Vatican controlled Roman Catholic Church, founding the Church of England in its place. He brought about the Dissolution and one of its major impacts was that the Catholic church’s vast landholdings, monasteries and other religious buildings were commandeered by Henry and his cronies.

Throughout the 15th and 16th centuries the City of London continued to become more successful, with its companies and the Livery Companies (Guilds, which I explain elsewhere) growing in wealth, power and prestige. This commercial success continued throughout the next two or three centuries. Trade with Europe and gradually the rest of the world, continued to grow. The formation of institutions by Royal Charter such as the Muscovy Company and the British East India Company which eventually ended up controlling most of India, meant that the City of London’s fortunes continued to soar.

In December 1664 another disaster hit London when the first fatality of the ‘Great Plague’ was recorded, and eventually one third of its population died from it. Recent excavations for Crossrail (the Elizabeth Line) construction project have uncovered several of the ‘plague pits’ where the bodies of victims, dying too quickly for proper burials to be arranged, were thrown.

However, hot on the heels (in more ways than one!) came the Great Fire of London in 1666.

The City’s old narrow medieval streets, with houses packed so closely together, meant that the fire was able to spread so quickly and wreak devastation on the City. However rebuilding started almost immediately, but now with far more building restrictions, such as houses spaced further apart and not constructed solely of wood, to try and avoid it happening again.

However, it was thanks to the vision, drive and enthusiasm of people like Christopher Wren that London literally arose out of the ashes. His contribution to the rebuilding of the City was inestimable and he was responsible for the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral, and over fifty other churches, preserving at least some of the City’s original character. Indeed, just thirty years after the Great Fire it was being said that the ‘streets of London were paved with gold’.

By now, the City’s success and its subsequent rising population had seen it spreading far beyond its previous boundaries. This growth was partly due to a rapid rise in immigration. Religious intolerance and persecution in Europe saw an influx of Huguenots from France and the Low Countries, many of whom settled in London and brought with them their specialist skills, such as weaving, clock, watch and jewellery making, further contributing to London’s financial success and wealth.

By the end of the 19th century London’s population was five times larger than it was at the beginning of the century. It had become the most prosperous, populated and influential city in the world. Its companies were trading with countries across the world and it was said that one fifth of the planet was ruled from London. Indeed the East India Company was at the time the biggest trading company in the world and ended up ruling over much of India for many years. Improved mechanisation saw factory output beginning to soar. At the same time transport links were rapidly being developed across the country. The Regent’s Canal had opened, enabling factory goods to be brought by barge from the industrial Midlands to London and the docks on the River Thames. Railways were spreading out from London to all parts of the country, again providing more markets for manufactured goods as well as bringing cheaper coal for the newly opened power stations in London, fresher food for City dwellers and much more.

The River Thames and the City’s growth

And here I must make a quick mention of the River Thames. Besides acting as the City’s southern boundary, there is no doubt that one of the main reasons for the City’s success has been the Thames. The Romans had realised the importance of the river and constructed the first quaysides. From the 10th century onwards the loading and unloading of cargoes, and all that goes with it, became the responsibility of companies based within the City, and very profitable it was for many hundreds of years.

Collecting taxes on imported goods – particularly high value cargoes such as spices, tea and coffee – were vital to Britain’s official ‘coffers’ and, by the 16th century, half of England’s customs revenue was being collected from cargos being unloaded in London. To ensure none were missed, the government decreed that only ‘Legal Quays’, where there was a Customs presence, could be used for this purpose and in 1558 twenty of these quays were licensed between the Tower of London and London Bridge.

However, as the shipping trade continued to rapidly grow, so did the queues of ships waiting to unload. Indeed, the situation became so bad that at times it was said to have been possible to have walked from the north bank of the Thames to the south bank by simply stepping on the decks of the moored ships, all waiting their turn to be unloaded. As this could take days or even several weeks to be done – and some cargoes were of perishable goods such as food – it was becoming a serious problem. In addition, there was the problem of ship owners having their expensive craft sat for long periods not earning any money. All of this resulted in the first of the London Docks being built – but even that wasn’t until 1799 (I cover more about this in more detail in the Tower Bridge to Canary Wharf Thames Walk).

But returning to the brief history of the City of London – it would be impossible to cover here the phenomenal growth and success of the City over the next two centuries. On my ‘Walk Two of the City of London’ we visit a number of significant buildings that were erected in the 17th and 18th centuries – for example the Royal Exchange in 1571; Edward Lloyd’s first coffee houses in 1652 (the forerunner of Lloyd’s Insurance Company, which was founded 120 years later in 1773); the Bank of England in 1691; the Stock Exchange in 1801 …

The success of London as a whole, of which the City of London was a significant ‘driving’ force, can be seen by the amazing growth In population; in 1851 London as a whole had just over 2½ million residents; fifty years later, at the end of Queen Victoria’s reign in 1901, it was more than 6½ million.

The 20th century

Jumping forward now to the 20th century – whilst the population of London as a whole continued to rise, the residential population of the City had actually been falling during the latter part of the 19th century. This had been encouraged by the better transport links provided by the early underground train networks, as people began to move further out into the new and expanding suburbs. However, as a result of the continual expansion of the City’s commercial and financial businesses, the actual numbers travelling in to work in the City was increasing.

The Second World War

Needless to say things changed rapidly following the outbreak of the Second World War. Destroying London was key to the German’s plan to demoralise the people and then invade England. Both the City and the neighbouring docklands and its associated factories were major targets for German bombing raids. Large swathes of the City and the docks and huge areas of the East End were reduced to rubble, reducing the population still further.

In total over 18,000 bombs were dropped on London. From September 1940 to May 1941 bombing raids were almost a daily or nightly occurrence – indeed, with the exception of just one day, there was a period of almost three months when bombs fell on London every night or day. Statistics vary, but it is said that over 30,000 Londoners were killed in the war, with over 80,000 seriously injured and a million houses damaged or destroyed.

By the end of the war the City of London was one of the worst damaged areas of the country. Many residential buildings had been so badly damaged they were demolished, and replaced by new office buildings, thus further speeding up the population decline.

The City of London in the 21st century

The City has always been somewhere that was frantically busy during the working week, with thousands of office workers flooding in every weekday. (Today there are said to be around 400,000 people working here, many in the financial services and insurance industries).

However, few people actually lived in the City so it was a different story in the evenings and at weekends when it would often be virtually ‘deserted’ and the restaurants, bars and shops closed, so even tourists didn’t bother to visit.

I understand that in the last census there were only about 9,000 people registered as living in the City, however, in recent years that is changing, and the population is said to be increasing. ‘Mixed use’ skyscraper developments, that offer both office space and residential apartments, are being built and perhaps to avoid long commutes, people are moving back in. Whilst some shops and bars still remain closed in the evenings and at weekends, many now stay open, particularly on Saturdays. Fortunately, there are still plenty of streets you can walk around and see little sign of life on a Sunday morning. Perfect for sightseeing, enjoying the atmosphere and taking photographs.

In addition to that, the City is also becoming more popular with tourists as a place to stay as well as visit, and over forty new hotels, offering well in excess of five thousand bedrooms, have either opened recently or will be opening over the next year or so. Whilst room rates are still generally expensive during the business week, they can be surprisingly attractive at weekends and in holiday periods.

How the City of London was, and in many cases still is, run

The Corporation of the City of London

Its official name is the ‘Mayor and commonality and Citizens of the City of London’ and it’s the “oldest continuous municipal democracy in the world”. Or to put it another way; “The world’s longest established local government authority”.

After William the Conqueror had invaded England in the Norman Conquest of 1066, he may have defeated the army, but he wasn’t prepared to do battle with the wealthy and prestigious City of London! So, in a Charter the following year, he granted various rights and privileges to the City, its merchants and citizens; many of those still hold good today. Further rights were granted to the City in the Magna Carta in 1215. The City also gained more independence in many areas from the Crown – too much money was being created by the City for them to dare to interfere.

There had been a form of organised ‘government’ in the City as far back as Saxon times, but this gradually became more formalised and by 1265 the Aldermen began to consult with a group of forty ‘wise and discreet’ citizens on various matters. The City had already been divided into wards and between one and four from men from each was selected. From 1376, this group had become more formalised and became known as the ‘Common Council’, which is still the vital part of the City’s government. (I mention the Wards again shortly).

The structure of the Corporation of London is still the same as it has been for many hundreds of years. At the top is the Lord Mayor, followed by the Court of Aldermen, The Court of Common Council and the Freemen and Livery of the City.

The Lord Mayor, who serves a one-year term of office, is chosen by fellow members of the Court of Aldermen. Whilst the role is largely ceremonial these days, it is still prestigious, though the Lord Mayor is expected to work extremely hard, which I explain more about next). And of course, it is important not to confuse the Lord Mayor of the City with the Mayor of London, a political post, who is elected by residents of the whole of London. There have now been nearly seven hundred Lord Mayors of the City since the role was established in 1687.

Alderman and Councilmen stand for election in each of the twenty-five wards, (more on those later), each ward being an electoral division. Residents and businesses based in the City are entitled to vote.

The Court of the Aldermen is chaired by the Lord Mayor and meets eight times a year.

The Court of Common Council is the primary decision-making body, and usually meets every month. As with any local authority it primarily works through committees but is unique in that it is non-party political.

The Role of the Lord Mayor of London

Whilst the Lord Mayor’s primary responsibility is to represent the City of London, it would be fairer to say that it actually means representing the City’s financial services sector – the banks, insurance companies, stock brokers … all of which are both the power house of the City as well as that of the country.

During their year in office the Mayor would often be attending between five and eight functions a day; they would make around eight hundred speeches in a year. The Mayor is also expected to travel extensively during their year of office. They would usually be abroad on official business for around a hundred days of the year.

The Mansion House

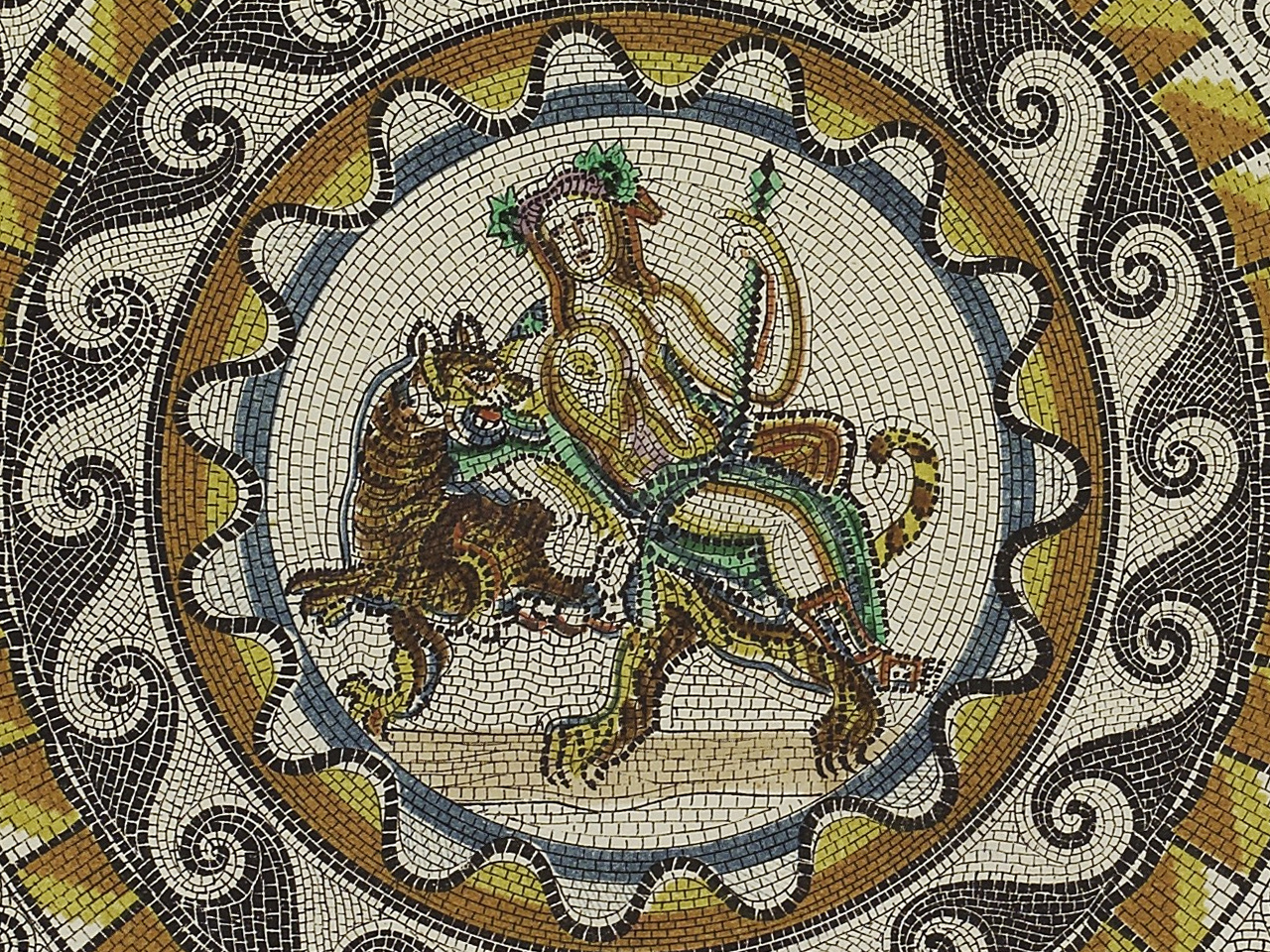

This is the official home of the Lord Mayor for the year they are in office. It was built in 1752 by the architect George Dance the Elder and the Palladium-style building is now Grade I listed. Outside, its six Corinthian columns support a pediment that has as its centre piece a ‘symbolic figure of the City of London trampling on her enemies’.

The most famous room, used for lavish receptions, is known as the ‘Egyptian Room’, on account of its marble columns

Besides the rooms used for hosting official functions, the Lord Mayor has his or her private apartments, and there are a further twenty bedrooms for staff and guests.

Some of the official functions are quite magnificent and politically very important. The ‘Easter Banquet’ has as its main speaker the current British Foreign Secretary, whilst the white tie dinner has as its principle guest and main speaker the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who uses the opportunity to talk about the British economy.

Interestingly, as the Lord Mayor was at one time also the City Magistrate, the Mansion House also had the courthouse within the building and there were twelve cells, eleven for male prisoners and one for women, in the basement. One of the more famous prisoners was Sylvia Pankhurst, who was held here on charges of sedition in 1930. The Magistrates Court is now in an adjacent building.

… and how the building of the Mansion House was funded …

I must just make mention here about the way in which the building of the Mansion House was funded. It was truly as unique as it was grossly unfair and actually rather wicked.

At the time there were a number of ‘dissenters’ living in London. These were people who opposed state interference in religion and turned their backs on the Church of England and Catholic Church. Many refused to take the Sacrament, a fundamental part of both church’s worship.

So, in order to raise the money for the building, the City authorities decided to only select ‘dissenters’ to stand for election as a Sheriff of the City of London. They did this because they knew the rules said that to be a Sheriff you had to have taken, and continue to take, the Church of England’s Sacrament – something they knew they wouldn’t be able to do.

At the same time, they brought in a new ‘law’ that said anybody who refused to stand for election to Sheriff would be subject to a huge fine, in today’s money equal to many thousands of pounds. And in so doing they systematically ruined a lot of people and raised enough money to build the Mansion House.

Guilds and Livery Companies

The majority of the City of London’s Livery Companies evolved from the medieval guilds that were to be found in many of the leading cities of Europe. Guilds are said to go back as far as Saxon times – groups of men from the same trade, would ‘adopt’ a local church, taking that church’s Saint as their patron. They gradually changed from being mainly religious fraternities into organisations that would regulate the trade or craft that the ‘members’ were involved with. Some people have referred to them as a medieval version of today’s employer’s associations and trading standards officers!

Realising that having some sort of official ‘recognition’ by the Crown would give them more authority, they began to apply for ‘Royal authorisation’ and by 1180 some were even being fined by Henry I for not having sought it. The Crown had quickly realised the benefits of working with these guilds. After all, they were generally made up of clever, skilled and hardworking men, many of whom were amassing considerable amounts of money – which of course Kings (and Queens) always needed more. So in return for paying taxes and making loans to the Crown, the Guilds, as they were by then officially known, demanded to be given various powers, usually connected to having the ability to restrict and supervise their particular trade or profession. This enabled them to do such things as limit the numbers able to trade or practice, prevent cheaper or inferior goods being imported from elsewhere in the country as well as from abroad, set prices, wages and ensure quality by setting up training schemes and apprenticeships. They also had to subscribe to a code of conduct. For example, any merchandise they sold had to be of a certain quality – butchers couldn’t sell rancid meat nor could bakers sell mouldy bread.

During the 14th century, members of different Guilds began to wear their own distinctive ‘livery’, or costumes, thus distinguishing themselves from other guilds. That was quite simply how the name ‘Livery’ companies came about and these uniforms or costumes evolved into a form of ceremonial dress, unique to each guild, that are still worn today at official events.

Throughout the 15th and 16th centuries the City of London thrived, as did the Livery Companies who were playing a vital role in its success and with the wealth they were creating they began to build elaborate headquarters, known as ‘Halls’, as they are still known today. These were often quite magnificent and elaborate buildings but sadly, many were destroyed as a result of bombing raids during the Second World War. However, nearly forty are still in existence and are often quite magnificent buildings that are elaborately furnished. We see a number of them in the City of London Walk 1, and some do occasionally open their doors to allow the public to have a look around – many do this on the annual London ‘Open Door’s weekend each September.

By the 16th century, control of the Guilds, or Livery Companies, as they had then become known, passed from the Crown to the Lord Mayor of London and his Aldermen.

As the Livery Companies increased in prosperity, they became increasingly protective of their own status (or perceived status) within the City. Huge rivalry began to develop between them as to which was the most important and a particular aspect of this was the ‘order of precedence’. Quite simply, this was the order in which each Livery Company would take part in ceremonial events like the Lord Mayor’s or royal processions through the City. Things got so bad that at times it could even result in violence. However, it was the Lord Mayor and Court of the Aldermen that again ruled on this, basing their decision on the size, strength and importance of each Company at that time – and although it was as far back as the early 16th Century, the rules they set for ‘precedence’ still hold to this day.

And in case you might be interested, the Order of Precedence is –

- Worshipful Company of Mercers (general merchants)

- Worshipful Company of Grocers (spice merchants)

- Worshipful Company of Drapers (wool and cloth merchants)

- Worshipful Company of Fishmongers

- Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths

- Worshipful Company of Skinners (fur traders)*

- Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors (tailors)*

- Worshipful Company of Haberdashers (clothiers in sewn and fine materials – e.g. silk)

- Worshipful Company of Salters (traders in salt and chemicals)

- Worshipful Company of Ironmongers

- Worshipful Company of Vintners (wine merchants)

- Worshipful Company of Clothworkers

* There was even a ‘battle’ between the Skinners and the Merchant Taylors for the sixth place, eventually resolved by allowing one to be in sixth position one year and the other the seventh, which would be reversed the following year … hence (it is often said) the expression we still use today: ‘being at sixes and sevens’.

The whole list of the present 110 Livery Company’s in London is actually quite fascinating, but too long to list here.

And in case you are wondering about the ‘Worshipful Company of …’ – this is how they are formally referred to. As far as I can make out nobody seems to know where the ‘worshipful’ came from – it was probably just because they thought that by putting ‘worshipful’ in front of Company it made themselves sound more important.

The social and economic conditions that gave birth to the old guilds have long since gone and their role now is often ceremonial, having little or no control over the trades they once represented. However, some still have regulatory or statutory functions: for example, the Goldsmiths and Fishmongers. Most now concentrate on their charitable work (over £50 million a year is given by these companies to charity), whilst some still support the modern equivalent of their past trades. For example, the ‘Horners’, a livery company that goes back as far as 1284 and who carved and fashioned horns for used for a variety of purposes, from carrying liquids through to musical instruments, now support the modern plastics industry by encouraging educational and training schemes.

More modern Companies cover trades and professions that didn’t exist in earlier times, such as the Air Pilots and Navigators and the Information Technologists.

Livery companies often became exceedingly wealthy bodies – so much so that they were able to take care of their members in ill-health and old age. Some set up their own schools and a few of these are still in existence today – e.g. The Stationers Crown Woods Academy and the prestigious Haberdashers School.

These days much of the great wealth they accumulated has gone, (though some have significant property holdings, especially in London) but as a result of their longstanding investments they are still able to do much charitable work.

In the past, ‘Liverymen’ would have started as apprentices in their respective trade or profession and upon finishing their apprenticeship they became ‘Freemen of the City of London’ – free from being an apprentice and with many privileges, which I explain more about next. (However, the sons of wealthy people would sometimes buy their way into a Livery Company, and in some cases, it was an honour bestowed on them at birth.)

Freeman of the City

In the 13th century a Freeman was exactly what the name implies – ‘free’ and not the property of a feudal lord. You could own land and make money as you wished. To carry on a trade within the City of London you would have had to have been a Freeman. Indeed, this was the case right up until Victorian times.

Being a Freeman had many privileges – and I must mention one that still holds good today. A Freeman could ‘drive sheep and cattle’ over London Bridge without paying a toll, therefore making a higher profit at market. Each year there is a ceremony when Freemen are invited to do just that! Normally held at the end of September, hundreds turn out to see the Freemen ‘driving their sheep’ across the bridge – in 2018 the procession was led by TV presenter Alan Titchmarsh. And the event also raises significant money for charity.

Some other privileges seem rather dubious. For example, Freemen arrested for capital offences such as treason or murder could request to be hung using a silk rope rather than a rough hessian rope that was used for the lower classes.

Another privilege was that they could carry their swords drawn, to protect themselves against thieves, something they are unlikely to do today. They were also exempt from the press gangs that would roam the city, particularly near the docks, looking for ‘volunteers’ to be ‘pressganged’ into naval service. And one privilege that could still be useful today is the right to be drunk and disorderly and be afforded a safe passage home!

These days, anybody who has been on the electoral list for the City of London may apply to become a ‘Freeman of the City’, though you must be nominated by two ‘Councilmen, Aldermen or Liverymen’. However, people who have made a significant contribution to public life can be granted an ‘Honorary Freedom’, the highest honour the City can bestow. Some famous Honorary Freemen include Benjamin Disraeli, Winston Churchill, Margaret Thatcher, Nelson Mandela, Florence Nightingale, Presidents Eisenhower and Roosevelt, Princess Diana – and more recently JK Rowling, Mary Berry and Dame Judy Dench.

Wards and watchmen of the City of London

Firstly the ‘wards’ – By 1550, the City of London was divided into twenty-five Wards and men from each would have to take it in turns to act as ‘Watchmen’ for a year, in addition to their normal work. These wards are still in existence throughout the City of London today, and as you walk around you will see signs on the walls of churches and other public buildings telling you which Ward you are in.

Each Ward, which were also known as Aldermanries, still returns up to two aldermen (depending on its size) to the Court of Alderman and each year one of these is elected as the Lord Mayor of the City of London. Wards also have ‘Beadles’, an ancient ceremonial office who accompany the Alderman on the various ceremonial occasions in the City.

The Wards are still used by the police for day to day policing, with each one having a constable assigned to it.

And watchmen … The term ‘watchman’, who were the forerunners of today’s police and fire service, goes back to biblical and then Roman times. They were men who would keep watch for untoward behaviour or events – whether invaders, criminals or a fire breaking out – and who would then either deal with the problem themselves or summon help from others. In England a statute in 1285 by King Edward reads …

“… and the King commands that from henceforth all Watches be made as it hath been used in past times that was from the day of Ascension unto the day of St. Michael every city by six men at every gate, in every borough by twelve men in every town, by six or four according to the number of inhabitants of the town. They shall keep the Watch all night from sun setting unto sun rising. And if any stranger does pass them by them he shall be arrested until morning and if no suspicion be found he shall go quit.”

STANDARD APPENDIX

‘A REVERIE OF POOR SUSAN’

I mention in the walk that in Wood Street, just off Cheapside, there’s a tiny ‘garden’ that occupies what was once the churchyard of ‘St Peter Cheap’. The church had been built in 1196 but was destroyed in the Great Fire of London and never rebuilt. It was in this churchyard that in 1791 William Wordsworth once stood and listened to a bird singing in the tree (I doubt it’s the tree that’s still there today!) and wrote the poem entitled ‘A Reverie of Poor Susan’, that recalls the memories awakened in a country girl in London on hearing a thrush sing in the early morning.

At the corner of Wood Street, when daylight appears,

There’s a Thrush that sings loud, it has sung for three years:

Poor Susan has pass’d by the spot and has heard

In the silence of morning the song of the bird.

’Tis a note of enchantment; what ails her? She sees

A mountain ascending, a vision of trees;

Bright volumes of vapour through Lothbury glide,

And a river flows on through the vale of Cheapside.

Green pastures she views in the midst of the dale,

Down which she so often has tripp’d with her pail,

And a single small cottage, a nest like a dove’s,

The only one dwelling on earth that she loves.

She looks, and her heart is in Heaven, but they fade,

The mist and the river, the hill and the shade;

The stream will not flow, and the hill will not rise,

And the colours have all pass’d away from her eyes.

Poor Outcast! Return — to receive thee once more

The house of thy Father will open its door,

And thou once again, in thy plain russet gown,

Mayst hear the thrush sing from a tree of its own.

The last stanza was omitted from all but Poor Susan’s earliest appearances, for reasons discussed in the poem’s Wikipedia article.

THE BANK OF ENGLAND

Established in 1694, it is the second oldest bank in the world (a Swedish bank is the oldest). Until it was nationalised at the end of the Second World War it was still a private bank with shareholders.

It’s been on this same site since 1734; the building you see today having been designed in stages by several architects, most notably Sir John Soane – a fascinating character who was a great collector of eclectic ‘objects. His house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields has been turned into an eccentric museum (See my Holborn walk for more details).

The Bank of England was regarded as being an architectural gem and ‘revered worldwide for its spectacular use of natural light and mesmerising effects of scale’. Sadly, in the 1920s, much of that building was demolished whilst renovations and extensions were taking place, an act that the architectural historian and writer Nikolaus Pevsner says “was one of architecture’s greatest losses” – a view shared by many. (And a point of interest for Bristolians – the design of the Commercial Rooms in Corn Street, built originally as a gentleman’s club and meeting place for businessmen and now a Wetherspoons pub – was greatly influenced by the design of the Bank of England – its architect was a pupil of Soane’s.)

Underneath the bank are the massive vaults that contain Britain’s gold reserves (or what remains of them since Gordon Brown flogged them off) as well as those of thirty other countries. There are said to be over five thousand tons of gold – around 400,000 bars. The keys to open the vaults are three-feet-long – so you’d need rather large trouser pockets to carry them around. And a little-known fact: the largest bank notes that are kept in the bank are called Titans – A4 sized and each worth £100 million.

You can’t visit the Bank itself, but you can visit its small museum that’s situated in Bartholomew Lane, down the right-hand side. Admission is free and it’s open Monday to Fridays.

MONUMENT TO PAUL REUTER

On the rear of the memorial to Reuter, it explains:

The supply of information to the world’s traders in securities, commodities and currencies was then and is now the mainspring of Reuters activities & the guarantee of the founder’s aims of accuracy, rapidity and reliability. News services based on those principles now go to newspapers, radio & television networks & governments throughout the world. Reuters has faithfully continued the work begun here. To attest this & to honour Paul Julius Reuter this memorial was set here by Reuters to mark the 125th anniversary of Reuters foundation & inaugurated by Edmund L de RothschildTD. 18.10.76

LEADENHALL MARKET

There is said to have been a market of sorts here since Roman times and evidence of it was discovered in the 1880s when, during rebuilding, workers discovered one of the supports of stone arches, and subsequent excavation revealed that this was part of the biggest basilica in northern Europe; the arches being supports for the arcades. These remains are housed in the basement of a barber’s shop at the corner of Gracechurch Street and Leadenhall Market. (More recent development work at 21 Lime Street has uncovered further Roman remains.)

However, the first real records show that by 1321 it was an established meeting place of the Poulterers (merchants selling poultry and game) whilst the Cheesemongers began bringing their produce to the market from 1397. It was then based in a series of courts behind the grand mansion of Neville House on Leadenhall Street.

In 1408 the former Lord Mayor Richard ‘Dick’ Whittington acquired the lease of the building, and shortly afterwards bought the land as well. It soon became one of the most popular places in London to buy fish, meat, poultry and game. The site grew in importance and a granary and even a chapel were built to cater for those visiting the market.

A few years later it was decided that the market was to be the only place in London where leather could be sold. Two hundred years later, in the 17th century, it was decided that Leadenhall Market was the only place in the City where cutlery could be sold.

In 1666 parts of the market were damaged in the Great Fire of London and it was subsequently rebuilt, this time with a covered roof and divided into three sections – a Beef Market, the Green Market and the Herb Market.

The market underwent a major transformation in 1881 when the Corporation of London authorised Horace Jones, who had already rebuilt Smithfield and the Old Billingsgate Fish Market, to do the same with Leadenhall. The earlier stone structure was replaced with the wrought iron and glass roof buildings that we see today, and which now have a Grade II listing.

A further restoration took place in 1991 and since then it has become a popular area for a selection of unusual shops and attractive places to eat.

Bearing in mind how picturesque the market is, it’s hardly surprisingly it is popular as a film location, including scenes in several Harry Potter films, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.

And I’ll add here a little about ‘Old Tom’. During the early 19th century he became the most celebrated character in the market. He was a gander (a male goose) who had come from Ostend to England as a result of his fascination with one of the lady members of his flock who was being shipped from Belgium to London for slaughter in the market. It is recorded that over two consecutive days, 34,000 geese were slaughtered in the market, but Old Tom managed to escape execution. As a result, he quickly became a local ‘hero’, a great favourite of the workers in the market and even a regular customer in the local inns, where he was fed titbits. He died in 1835 at the formidable age of 38 and, after lying in state in the market grounds, he was buried there.

Old Tom’s fame was such that his obituary even made it into The Times newspaper. It was published on 16 April 1835 and read –

In memory of Old Tom the Gander

Died 19th March, 1835, aged 37 years, 9 months, and 6 days.

‘This famous gander, while in stubble,

Fed freely, without care or trouble:

Grew fat with corn and sitting still,

And scarce could cross the barn-door sill:

And seldom waddled forth to cool

His belly in the neighbouring pool.

Transplanted to another scene,

He stalk’d in state o’er Calais-green,

With full five hundred geese behind,

To his superior care consign’d,

Whom readily he would engage

To lead in march ten miles a-stage.

Thus a decoy he lived and died,

The chief of geese, the poulterer’s pride.’

THE ROMAN BASILICA

I have mentioned the Roman Basilica* that part of Leadenhall Market was built upon, so I thought a few words of explanation might be helpful.

Little was known about it until the construction of the present Leadenhall Market in the 1880s, when they discovered one of the supports of the many arches it had … in the basilica’s arcades. These remains are housed in the basement of a barber’s shop at the corner of Gracechurch Street and Leadenhall Market. More recent development work at 21 Lime Street has uncovered considerably more.

The basilica was originally built in AD70 and enlarged between AD90 and AD 120. It was certainly big – said to be the biggest ever built in Britain – and though not so high (around three storeys) its site was bigger than the present St Paul’s Cathedral, covering nearly two hectares. It was said to have been the biggest Roman basilica in Northern Europe.

It was eventually destroyed some two hundred years later by the Romans themselves as a punishment for the City supporting the ‘rogue’ Emperor Carausius.

* A basilica was a civic centre, with the offices of all the City’s officials and included an assembly hall, law courts, the treasury etc.

LLOYD’S OF LONDON

Lloyd’s is the largest insurance broker in the world and has been in existence for nearly 320 years. Multiple financial backers, known as ‘Names’, or corporations, join together here to pool and spread insurance risks. It is reckoned by many to be the ‘safest place in the world’ to trade in what can be the enormous insurance premiums of paid by international businesses and organisations.

As I’ve written elsewhere, it started in 1688 in Edward Lloyd’s coffee house in the City, a popular place for sailors, merchants and ship owners. Edward would pass on to them reliable shipping news gleaned from his customers and a variety of other sources. As a result, ship owners, merchants, ship’s captains etc. would meet here and amongst things they would discuss was insurance.

This continued after Edward died in 1713, but then in 1774, members of the informal insurance ‘arrangement’ that had been formed moved to the Royal Exchange.

Unfortunately, many of the valuable and now historic early records of Lloyd’s were destroyed in the Royal Exchange fire in 1838.

An Act of Parliament in 1871 gave Lloyd’s a more formalised legal structure as did a further act in 1911.

THE BALTIC EXCHANGE

The beginnings of the Baltic Exchange go back to 1744. Coffee houses had become important places for merchants and ship’s captains to meet to exchange news, and eventually do business and the original exchange set up in the ‘Virginia and Baltick* Coffee House’ in Threadneedle Street. It led to the formation of an actual ‘exchange’.

* This was the correct spelling at the time

There used to be a trading floor, similar to the Stock Exchange’s, but now most of the trading is done by telephone.

The exchange provides daily market prices and maritime shipping costs that are used by freight traders across the world and up to seven ‘Indexes’ are published.

ST ETHELBURGA THE VIRGIN CHURCH – and the IRA bombing of Bishopsgate

At 10.27 on the 24th April 1993 one of the biggest IRA bombs ever to be detonated in Britain exploded in Bishopsgate.

It had been placed inside a stolen tipper truck that was parked outside the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank at 99 Bishopsgate. Most buildings within a 500-yard radius were extensively damaged, including the NatWest Tower (now Tower 42) and even Liverpool Street station.

Fortunately, it was a Saturday and only one person was killed, though forty-four were injured, and £350 millions of damage was caused.

A year before the IRA had planted a bomb just a few hundred yards away outside the Baltic Exchange in St Mary Axe that killed three and injured 91. Following that attack the police introduced what was called a ‘Ring of Steel’ that surrounded the City of London. Manned barriers were erected at all the roads entering the area and police were routinely armed.

The Bishopsgate bomb was the last major attack on British soil by the IRA.

Unfortunately, one of many major victims of the blast was St Ethelburga’s, a Grade I listed medieval church that had survived both the Great Fire and the Blitz. Sadly, the blast from the bomb virtually destroyed the church. It has been rebuilt and is now a Centre for Reconciliation and Peace, a multi-faith non-profit charity that runs conferences and training courses to bring together people from different parts of the world and different religions to encourage both understanding and forgiveness.

LONDON SKYSCRAPERS

I have mentioned new skyscrapers in several places during the walk, as they seem to be popping up all over the place. As of 2018 there were 510 tower blocks over 20-storeys high planned for Greater London, of which construction had already started on 115.

One of these is going to be ‘One Leadenhall Street’, a 36-storey, 600 feet high office block that is planned to be finished in 2021. It’s attracted considerable criticism from conservation, environmental and historical charities and organisations for its size and design, particularly as it will overlook the roof of the adjacent Grade II listed Victorian Leadenhall Market. It is replacing a 1970s seven-storey office block.

However, it will be dwarfed by Number 1 Undershaft, a 73-storey skyscraper nicknamed The Trellis – which will be the second tallest building in Europe after the Shard.

At 22 Bishopsgate they are building the ‘Pinnacle’, which when it’s completed will be the tallest in the City of London at 59-storeys – 278 metres (over 900 feet high). It was originally going to be 62-storeys, but there were concerned that the height of the cranes needed to build it would cause problems for aircraft heading for the London City Airport.

A list of the City of London’s tallest buildings (as at end 2018 – and I have included the Shard and One Canada Square, which are outside of the City) looks like this –

1,016 ft (310m) The Shard – built – 95 floors

951 ft (290m) 1 Undershaft (known informally as ‘The Trellis’), due to its external cross bracing – building about to start – 73 floors – replaces the Aviva Tower, that was built in 1969

912 ft (278m) 22 Bishopsgate – under construction 62-floors

826 ft (263m) The Diamond – (100 Leadenhall Street) – construction about to begin – 56 floors

770 ft (235m) One Canada Square – 50 floors, built in 1998 in Canary Wharf

770 ft (235m) Spire London – under construction

764 ft (233m) Landmark Pinnacle – under construction

757 ft (231m) Heron Tower (110 Bishopsgate) – 46 floors – built

738 ft (225m) The Cheesegrater (The Leadenhall Building) – built

623 ft (190m) The Scalpel (52 Lime Street) – 39-floors – built

597 ft (183m) 1 Leadenhall Street – 38 floors – under construction

593 ft (181m) 100 Bishopsgate – 40 floors – under construction

590 ft (180m) The Gherkin – (St Mary Axe)– built – 40 floors

However, the City’s latest skyscraper could be a giant tulip. Foster + Partners, the architects behind the Gherkin, have submitted plans to build the tallest structure in the City of London, and just a fraction shorter than the Shard, currently Britain’s tallest building.

Apparently, this would be more of a ‘novelty’ skyscraper, possibly better described as an ‘observation tower’ whose design has been said to resemble a ‘fungal growth, like a fruiting body laden with spores’. In other words, perched on the top of the narrow tube-like tower is what could be considered a miniature Gherkin – though it’s being called a ‘tulip’ instead.

The planning application includes a public roof terrace, restaurant, bar and viewing gallery.

And where would it be built? Actually, next to the Gherkin itself!

Finally, a spot of trivia

THE ROADS LEADING OUT FROM LONDON

I mention in the walk how many A-roads spread out from London. To add to that, I’ll mention something that not many people are aware of, yet it can be quite useful.

All ‘A roads’ that are numbered from 1–11 start in London but are in ‘quarters’ – so using a clock face as an example, between 12.00 and 3.00 (in other words from points north to east), all ‘A’ roads leading out from London begin with the number ‘1’.

Those leaving London from ‘3.00 to 6.00’ (from points east to south) begin with a ‘2’.

From 6.00 to 9.00 (points south to west) they begin with a 3.

And … yes, you’ve got it … from 9.00 to 12.00 with a ‘4’.

Hence the four principle four roads out of London are the A1 to the north, the A2 that leads to Dover in Kent, the A3 to Portsmouth and the A4 to Bristol.

And within these ‘quarters’, the ‘lesser’ A roads will also start with the relevant number … so between the A1 and the A2 you have the A12, A13 etc.

And most other roads within each of those ‘quarters’ will also begin with the same number – i.e. most A roads in the southeast of England have a ‘3’ as their prefix whilst those in the west with a ‘4’. So, in the West of England most ‘A’ roads begin with a ‘4’ – i.e. A46, A412, A420 etc.