Updated: 3 June 2023 |

|

Walk page: Click to view |

Appendix to the Covent Garden walk

MORE INFORMATION ON COVENT GARDEN

Extra information about some of the most significant places, subjects and people mentioned in the Covent Garden walk, together with pictures.

OUTERNET

I’ve already written about the ‘Outernet’, in particular quoting from The Guardian newspaper, which also added: “Outernet CEO Philip O’Ferrall calls his project ‘the world’s largest, most advanced atrium of content … a disruptive, atomised brand engagement platform,’ by which he means that companies will pay handsomely to put their brands on the big videos, and to hold spectacular events in the screen-lined rooms. The idea is to entice the public in and then get them to linger, with the imagery on the screens, with the music, with bars and restaurants, such that they can be exposed to more selling. ‘If you spend an extra 30 seconds in my area I can serve more advertising on you,’ he says. The revenues, O’Ferrall also explains, will help fund the less profitable music businesses on the other side of the block.”

I make no comment!

THE COLISEUM

The Coliseum was the idea of theatre producer Sir Oswald Stoll, who had great aspirations of building the “largest people’s palace of entertainment in the West End.”

It was designed by the theatrical architect Frank Matcham in an Italian Renaissance style and opened in 1904.

It wasn’t just its imposing size but when it was built it had a roof garden, which was removed in 1951. The square tower on the roof has four pilasters and carved figures representing Art, Music, Science and Architecture. Other decoration includes at the pinnacle eight Cupids that support a large, illuminated globe, which when it was built used to revolve.

The theatre had electric lighting, and a massive revolving stage (the first in Britain) which was actually made up of three smaller ones, each of which could revolve independently and in different directions. This enabled much faster set changes to take place.

Another first were the lifts to take customers to the upper-level seats (including a private one to take the King to the Royal Box).

In addition, it had several restaurants and tea rooms and even its own post office in the lobby to enable both performers and the public to send and receive telegrams.

Despite all of that, it wasn’t a commercial success, and closed just two years after opening.

After it reopened in December 1907, a cricket match was held between Middlesex and Surrey, and then featured the last work by W.S. Sullivan (of Gilbert & Sullivan fame).

In the 1930s they successfully began featuring pantomimes, with Cinderella always being the most popular.

Whilst this run of success lasted for some thirty years, falling ticket sales resulted in it becoming a cinema in the 1960s, showing films using the latest wide Cinerama format. It had been used sporadically for films previously – King Kong was shown in 1933, with a run of many months and up to 10,000 people a day seeing it. Another great cinema success was a revival of Gone with the Wind.

Another major change occurred in 1968 when the Sadler’s Wells Opera Company began using the theatre, later changing their name to the English National Opera Company and, in 1992, purchasing the freehold of the theatre for just over £12 million. It also became the home of the English National Ballet.

It wasn’t all highbrow entertainment, as the rock band The Who performed at the Coliseum in December 1969. The concert was recorded – and is still available on DVD.

With 2,359 seats, the Coliseum is still the largest theatre in London, unless you include certain venues that only occasionally stage theatrical or ballet productions, like the Royal Festival or Albert Halls. For comparison purposes, as of May 2023, the Apollo Victoria runs it a close second with a capacity of 2,328, the Palladium seats 2,286, the Lyceum 2,167, the Theatre Royal Drury Lane 2,154 and the Dominion in Tottenham Court Road 2,069.

COVENT GARDEN MARKET

Its early years

The fruit, vegetable and flower market began in 1656 with a few ‘temporary’ stalls erected alongside the walled garden of Bedford House, home of the Earl (later Duke) of Bedford. Controversy soon began, with concern over the amount of rubbish being left at the end of each working day.

By 1667 the commissioners for highways and sewers were discussing what to do about the “great ffylth” generated by the traders. Three years later, in 1670, the 5th Earl of Bedford and his heirs were granted a licence by Charles II to hold a market for ‘fruit, flowers, roots and herbs’ and to collect tolls and fees from the dealers every day of the year, with the exception of Sundays and Christmas Day. As a result, permanent shops were erected against the garden wall of his home at Bedford House.

Then just eight years later, a lease was granted to Adam Piggot, giving him the right to erect twenty-two permanent shops, with cellars against the garden wall of Bedford House, to buy and sell fruit, flowers, roots and herbs. After the house was later demolished, a row of forty-eight shops was built nearer to the centre of the piazza, which I do find surprising as, whilst all of this was taking place, this was still a fashionable residential area in which to live.

However, there were complaints, and the Vestry of St Paul’s church presented a petition to the duke complaining of the nuisance of the market, though seemingly nothing actually changed. On the contrary, the market became larger. The closure of another major market several miles away in the City of London saw a further significant increase in Covent Garden’s trade.

During the late 18th and early 19th century the character of both the market and the neighbourhood continued to change. The market became busier, but rather than just selling fruit, vegetables and flowers, these new traders began selling various other goods.

The original stall holders protested and refused to pay their rent until this was stopped. The Duke of Bedford, (now the 6th, who still owned both the land and the freehold of the market buildings), went to parliament to ask them to define his authority. The result included permission to erect new buildings where market holders could carry on their business in defined areas.

This meant building on what had hitherto been Inigo Jones’ magnificent open piazza and the new building opened in 1836. Designed by Charles Fowler, it was described by the Gardener’s Magazine as “a structure at once perfectly fitted for its various uses; of great architectural beauty and elegance; and so expressive of the purposes for which it is erected, that it cannot by any possibility be mistaken for anything else other than what it is.” Quite some praise.

However, the market was still growing – so much so that within twenty-five years its buildings had to be extended again. In 1860 the Floral Hall opened. It had been designed by E.M. Barry, the son of Sir Charles Barry, who had rebuilt the Palace of Westminster following the disastrous fire.

These were followed by the building of the Flower Market in 1871 and later the Jubilee Market.

The popularity of the market was now such that it had become what was described as a “colourful, lively and popular place where fashionable Londoners like to mingle with farmers, costermongers and flower-girls.” Charles Dickens lived nearby and wrote that he liked to go and gaze at the pineapples when he had no money.

The market in the 20th century

By the start of the 20th century, the market employed nearly a thousand porters and they were paid between 30 and 45 shillings a week. Initially many had been women, but gradually men, particularly Irishmen, were taking over these roles. The market’s activities were supervised by twelve managers of the Bedford Estates Company, together with seven policemen, who were hired from the Metropolitan Police. Despite this, the market continued to be an ‘unruly and ill-organised’ place and the Bedford family decided to give up ownership. It was offered to the City Corporation and the Metropolitan Board of Works, but neither was interested, so in 1918 it was sold to a newly created Covent Garden Estate Company. Just two years later they in turn tried to sell the market to the London County Council, but without success.

There had been plans to move the market since the end of the First World War, but those had been fiercely opposed by locals and most of those people who depended on it for a living. An official report by the Ministry of Food in 1921, described the market as condemned and ‘unfit for purpose’ … ‘a confused and unorganised anachronism’ and that it was inadequate and uneconomic, in ‘that supplies were brought into the Market at heavy expense, and then sent out again’. However, even despite this, it continued operating on the site until eventually being sold in 1962 to the Covent Garden Market Authority. They paid almost £4 million for it, together with some of the adjoining properties. Finally, in 1974, the market closed and was relocated to a purpose-built complex at Nine Elms, south of the river.

Many of the empty market buildings were taken over by the Greater London Council, who announced a plan for 60% of the area to be demolished, including over 80% of all the housing. In its place would be a new conference centre, offices, hotels and housing estates, as well as new, wider roads.

Fortunately, in 1971, the Covent Garden Community Association was formed, and they campaigned to have these proposals scrapped. Eventually, as public opinion also turned against the scheme, the plans were dropped, and fortunately we still have much of the original market buildings intact for us to enjoy today.

QUEEN OF COVENT GARDEN

I made mention of Christina Smith in the walk and thought I’d add more about this remarkable woman here. Christina was what we’d today call a ‘legend’ and is credited with doing as much as or more than anyone to help save Covent Garden from the council and developers who wanted to demolish most of it and build modern office blocks, an enormous conference centre, hotels and much more.

Following her death in 2022, such was her reputation that The Times published an extensive and revealing obituary, from which I’ve reproduced a handful of informative extracts:

Christina Smith was walking through Covent Garden in the early 1960s when she spotted a ‘to let’ sign on a former potato warehouse. Excited by its potential and enthralled by the ‘seedy atmosphere and the seedy people’ of the bustling fruit and vegetable market, she borrowed £1,500 from her father and opened Goods and Chattels, importing and wholesaling colourful trinkets from South America.

It was the start of a multimillion-pound property and retail empire, with the former propping up the latter to create the quirky, colourful shops for which Covent Garden became famous. Her philosophy was an eclectic combination of business and philanthropy.

Known as the ‘Queen of Covent Garden’, Smith was also a restaurateur, philanthropist, conservationist, mentor, art collector and theatre angel.

She was a tall woman with scraped-back hair, loud clothing and huge tinted glasses that matched her ego. She was, however, a terrible delegator, leaving many of her managers feeling underemployed and undermined. There was always a sense of drama. On one occasion she met a friend at the Tea House, another of her enterprises, entertaining him and the customers by chastising the manager because the mugs and teapot were cracked. Some days later the manager revealed to her friend his increasingly plaintive memos requesting new crockery, all of which had gone unanswered.

After the fruit and veg market moved from Covent Garden to Nine Elms, in Vauxhall, in 1974, she was involved in saving the area from developers’ proposals for a conference centre, a large hotel, offices and a new road layout. The market hall survived, as did another 250 buildings that were declared to be of historic and architectural interest. As a member of the Covent Garden Community Association, the Seven Dials Trust and the Covent Garden Forum, her eagle eye meticulously scrutinised every planning application. “I wanted to preserve the buildings and protect the residents,” she said.

THE HISTORY OF THE IVY

I’ve written a little about the Ivy restaurant in the walk, but I find its history very interesting, so I’ve taken various bits from a fascinating book called The Ivy Now, by Fernando Peire and Gary Lee, and published by Quadrille. If you’re interested in knowing more about the history of the restaurant, then I suggest you read a copy.

Mario Gallati was less than impressed when he first walked into The Ivy after arriving in London from Italy. Opened in 1917 by Abel Giandolini, it had lino on the floor, paper napkins on the tables and no alcohol licence.

Gallati already had the offer of a job as head waiter at Romano’s, an established Italian restaurant in Soho. It was the epitome of glamour, where the capital’s great and good dined alongside London Bohemia. Now he found himself presented with a new opportunity by a young entrepreneur. Giandolini aspired to create one of the city’s finest restaurants and, after several meetings with him, Gallati finally agreed to join him as maître d’. Soon the tables were covered with linen, the floors carpeted, and a French chef installed in the kitchen.

Key to The Ivy’s initial success was its location, surrounded by many of London’s top commercial theatres. Ivy waiters were soon delivering meals of cold chicken and salad to the dressing rooms of hungry actors.

A licence to sell alcohol was essential if they were to become a successful restaurant, and when they applied to get one, Winston Churchill was among those who signed a petition in support. Once they had it, then Gallati devoted himself to buying up private wine cellars at auction and, before long, the wine list rivalled that of the great hotels. Location, food and wine combined to draw London’s theatre crowd through the doors. It was a non-stop party – attended by politicians, entrepreneurs, intellectuals and names from the worlds of theatre and film. Later, looking back on his time at The Ivy, Gallati found it impossible to list exactly who had eaten there during his 28 years. ‘It would probably be easier to say that everyone who was anybody in London between the wars dined at the restaurant,’ he wrote.

But Gallati realised that he could not hide away at The Ivy forever. He found investors among his old Ivy clientele and took a chance on a restaurant at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac behind The Ritz. A rivalry between Giandolini and Gallati started and continued until Giandolini sold The Ivy in 1953 to the Wheelers Group of fish and seafood restaurants. The first golden era of The Ivy had come to an end, and it would be almost 40 years before it would dominate the society columns again.

The celebrity era begins

By the late 1980s, the ‘grande old dame’ of Theatreland had traded continuously for almost 70 years but had lost much of her lustre. It took two ambitious restaurateurs, Christopher Corbin and Jeremy King, who bought it in 1989, to bring about her transformation, and underwent the most radical change since Gallati and Giandolini had expanded the dining room in 1929. It creaked with nostalgia, but Corbin and King did not want it to lose its character in favour of a modern interior; instead they chose to acknowledge its past.

In the 1990s the likes of the band Oasis, the Spice Girls and The Verve all became regular customers of The Ivy. It had now become a haven for both the establishment and the anti-establishment. Cool new artists like Damien Hirst, Marc Quinn and Tracey Emin embraced it, as did the new breed of young theatre producers who were busy shaping the future, not only of theatre, but of film – people like Sam Mendes at the Donmar Warehouse theatre, Stephen Daldry at the Royal Court and Nicholas Hytner at the National Theatre.

The Ivy held up a mirror to the capital – showing it in the most flattering light possible and magnifying its glamour many times over. Sometimes it seemed as if the whole of the London artistic scene was in the dining room. However well known the restaurant became, they made sure that it remained a private world. Every flash of the paparazzi’s cameras and every front-page photo of a star leaving, only added a little more to its special allure. It was a unique moment for a London restaurant.

And the final word goes to Fernando Peire who joined The Ivy in 1990 as senior maître d’, and who is now director of the restaurant and club:

Every day and every night, The Ivy is a stage on which a play is performed. The actors are the regulars drawn from the worlds of the arts and business who have more than a passing interest in who’s eating with whom and sneaking glances to see how X is looking, after Y sued or seduced them; they are famous people who want to be seen, sheltered or something in between; they are characters in a personal story of a couple on a first date, a family celebration or one friend gossiping with another.

Some of these players sit in the wings, others take centre stage, but all have their part to play. The Ivy is theatre. There is just one golden rule: there are no stars of the show. The Ivy might be good at letting people perform, but it isn’t a restaurant for show-offs. We like to think of it as a meritocracy. Some people may be able to get a reservation more easily than others, but once in The Ivy, everyone is equal. So, welcome.

MORE ON MONMOUTH STREET

The following is taken from Charles Dickens’ Sketches by Boz – ‘Scenes: Meditations in Monmouth Street’:

“We have always entertained a particular attachment towards Monmouth Street, as the only true and real emporium for second-hand wearing apparel. Monmouth Street is venerable from its antiquity, and respectable from its usefulness. Holywell Street we despise; the red-headed and red-whiskered Jews who forcibly haul you into their squalid houses, and thrust you into a suit of clothes, whether you will or not, we detest.

“The inhabitants of Monmouth Street are a distinct class; a peaceable and retiring race, who immure themselves for the most part in deep cellars, or small back parlours, and who seldom come forth into the world, except in the dusk and coolness of the evening, when they may be seen seated, in chairs on the pavement, smoking their pipes, or watching the gambols of their engaging children as they revel in the gutter, a happy troop of infantine scavengers. Their countenances bear a thoughtful and a dirty cast, certain indications of their love of traffic; and their habitations are distinguished by that disregard of outward appearance and neglect of personal comfort, so common among people who are constantly immersed in profound speculations, and deeply engaged in sedentary pursuits.

“We have hinted at the antiquity of our favourite spot. A ‘Monmouth-street laced coat’ was a by-word a century ago; and still we find Monmouth-street the same. Pilot great-coats with wooden buttons, have usurped the place of the ponderous laced coats with full skirts; embroidered waistcoats with large flaps, have yielded to double-breasted checks with roll-collars; and three-cornered hats of quaint appearance, have given place to the low crowns and broad brims of the coachman school; but it is the times that have changed, not Monmouth-street. Through every alteration and every change, Monmouth Street has still remained the burial-place of the fashions; and such, to judge from all present appearances, it will remain until there are no more fashions to bury.”

“We have always entertained a particular attachment towards Monmouth Street, as the only true and real emporium for second-hand wearing apparel. Monmouth Street is venerable from its antiquity, and respectable from its usefulness. Holywell Street we despise; the red-headed and red-whiskered Jews who forcibly haul you into their squalid houses, and thrust you into a suit of clothes, whether you will or not, we detest.

“The inhabitants of Monmouth Street are a distinct class; a peaceable and retiring race, who immure themselves for the most part in deep cellars, or small back parlours, and who seldom come forth into the world, except in the dusk and coolness of the evening, when they may be seen seated, in chairs on the pavement, smoking their pipes, or watching the gambols of their engaging children as they revel in the gutter, a happy troop of infantine scavengers. Their countenances bear a thoughtful and a dirty cast, certain indications of their love of traffic; and their habitations are distinguished by that disregard of outward appearance and neglect of personal comfort, so common among people who are constantly immersed in profound speculations, and deeply engaged in sedentary pursuits.

“We have hinted at the antiquity of our favourite spot. ‘A Monmouth-street laced coat’ was a by-word a century ago; and still we find Monmouth-street the same. Pilot great-coats with wooden buttons, have usurped the place of the ponderous laced coats with full skirts; embroidered waistcoats with large flaps, have yielded to double-breasted checks with roll-collars; and three-cornered hats of quaint appearance, have given place to the low crowns and broad brims of the coachman school; but it is the times that have changed, not Monmouth-street. Through every alteration and every change, Monmouth Street has still remained the burial-place of the fashions; and such, to judge from all present appearances, it will remain until there are no more fashions to bury.”

VISITING COVENT GARDEN’S MARKET IN THE 19th CENTURY

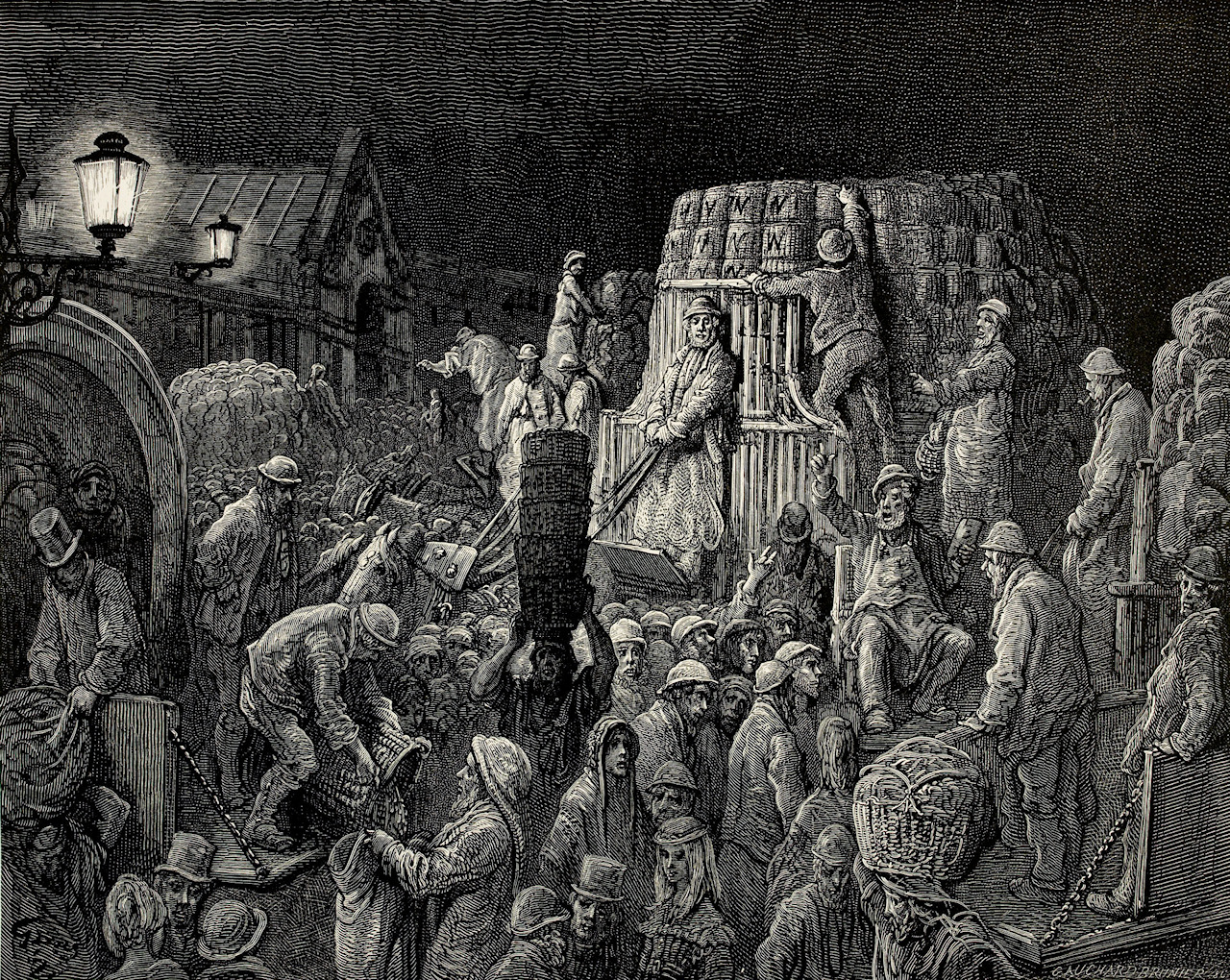

I liked this account of visiting the market, written by William Blanchard Jerrold and published in London: A Pilgrimage (1872), with illustrations by Gustave Doré.

Covent Garden Market, however, is the most famous place of barter in England: – it has been said, by people who forget the historical Halle of Paris – in the world. A stroll through it, and around it, when the market is opening on a summer morning, between four and five, affords the visitor a score of points of interest, and some matter for reflection. As at Billingsgate and in the Borough, the surrounding streets are choked with waggons and barrows. The street vendors are of all kinds – and of the poorest of each kind – if the coffee stall keepers be excepted.

The porters amble in all directions under loads of prodigious bulk. Lifted upon stalwart shoulders, towers of baskets travel about. From the tails of carts producers or ‘higglers’ are selling off mountainous loads of cabbages. The air is fragrant with fruit to the north, and redolent of stale vegetables to the south. The piazzas, of pleasant memory and where a few noteworthy social clubs still linger, are alive with stalls, scattered sieves, market-gardeners, greengrocers, poor women and children in troops (these are everywhere on our way), and hawkers old and young eagerly on the lookout for an advantageous transaction with a higgler, or direct from the producer. Within the market enclosure the stacks of vegetables, and the piles of fruit baskets and boxes, are of startling extent.

The scene is not so brilliant as that we used to see about the old fountain at the Paris Halle, where the water seemed to spring from a monster horn of plenty; but these Irish women, these fresh-coloured Saxon girls, these brawny Scotch lasses, in their untidy clothes and tilted bonnets, who shell the peas, and carry the purchaser’s loads, and are ready for any of the hundred-and-one jobs of a great market; fall into groups wonderfully tempting to the artist’s pencil.

We lingered long one morning, watching a group of women shelling peas. They were a picture perfect in all its details, with the majestic old woman, who commanded the company, for central figure.

“It would be nothing without colour – and more space than any page affords,” was my fellow pilgrim’s remark. “It’s a pity, but so it is.”

It was in the poor markets, it need hardly be said, that we found our most striking subjects; and ever as we neared the poorest, we saw the buyer at a fresh disadvantage. In Covent Garden, there is the higgler, or middle-man, who buys from the producer to sell to the retailer, who will, in his turn, sell to the humble customer. The rich man buys first-hand; the poor man, fifth-hand.

PUNCH & JUDY

Whilst Punch & Judy has been a staple of seaside entertainment for children as far back as Victorian times, over recent years it began to lose much of its appeal. Public opinion has changed, with many people saying that it trivialises domestic violence and abuse.

Rightly or wrongly, when I was a child I used to love it, and it never occurred to me that it had ‘sinister overtones’.

Whilst researching this I found a few pieces of information that I found interesting, and thought I’d share here …

- Punch & Judy puppeteers are called Professors, having apparently once been given this title by the King.

- The phrase ‘pleased as Punch’ was said to have come about as a result of Mr Punch invariably being very immensely pleased and satisfied with everything he does. As was the phrase, “That’s the way to do it!”

- Punch & Judy shows used to have a ‘Bottler’ – this was someone who would go around gathering up people to come and watch the show, and then collect money for the puppeteer in a bottle. He would often play music on a guitar or drum to accompany the show and create sound effects.

- In early Punch and Judy shows, Punch regularly got into fights with the Devil. In contemporary Punch and Judy performances, the Devil has transformed into a crocodile, his new biggest adversary.

For anyone interested in learning a little more about the story of Punch & Judy, particularly its more controversial side, I found a fascinating article online here.

DAVID GARRICK

David Garrick had a huge impact on British theatre, and indeed on the Covent Garden area. I read a biographical summary in Brief Lives: Sitters and Artists in the Garrick Club Collection (London: Garrick Club, 2003), written by the late Professor Kalman A Burnim, and I’ve reproduced some extracts here:

David Garrick, the second son and third child of Peter and Arabella Garrick, was born at the Angel Inn, Hereford, on 19 February 1717. David’s grandfather, David de la Garrique, was a Huguenot who fled France in 1685, and David’s father Peter was brought to England in 1687. Our David was for a while one of Samuel Johnson’s pupils at the little school at Edial, near Lichfield.

Later, in 1737, Garrick and Johnson made their way to London together, with little money in their pockets, but each destined for fame. Garrick was to serve as a wine salesman for the family business, but he soon pushed that trade out of his mind and turned playwright and actor. He made his debut as Richard III at the Goodman’s Fields Theatre in east London on 19 October 1741.

He was an overnight sensation. His revolutionary and exciting acting style ‘threw new light on elocution and action,’ banished ranting and bombast, and ‘restored nature, ease, simplicity, and genuine humour.’

In the autumn of 1747, with his new partner James Lacy, Garrick took over the management of Drury Lane Theatre, and for 29 years he directed the finest repertory theatre in all Europe. As a pivotal figure in the development of the art of the theatre he instituted new rehearsal techniques and discipline.

The techniques of the theatre arts – scenery, costumes, lighting and other stage practices – significantly matured. Garrick maintained a strong company and demanded their adherence to his instructions and regulations.

In 1749 Garrick married the Viennese dancer Eva Maria Veigel. She outlived him by 43 years. They had no children. During their marriage they enjoyed the company of crowned heads, nobility, and the leading figures of London literary and social circles. They owned residences at No. 27, Southampton Street in Covent Garden, in the Adelphi and on the river at Hampton. The Shakespeare Temple that Garrick had erected at the Hampton villa has recently been restored and opened to the public.

Garrick gave up Drury Lane and made his farewell from the stage in a round of emotional performances in June 1776. He died at his home in the Adelphi on 20 January 1779 and was buried in Poet’s Corner, Westminster Abbey. The splendid funeral procession, one of the greatest ever seen in London, stretched from the Strand to the Abbey. His old schoolmaster Johnson wrote, ‘I am disappointed by that stroke of death which has eclipsed the gaiety of nations and impoverished the public stock of harmless pleasure.’

BOW STREET MAGISTRATES COURT

Bow Street Magistrates Court had a long and interesting history dating back to 1740. This was when Thomas de Veil established a private residence and magistrate’s office at number 4 Bow Street, opposite where the court moved to in 1881. As an aside, he must have been quite a character and was said to have had four wives and twenty-five children.

He lived in the house whilst practising his magisterial duties from the ground floor. It later became London’s first police station and over time the most important of the capital’s magistrates’ courts. Following his death in 1746, the house at No.4 Bow Street was taken over two years later by another magistrate, Henry Fielding, who had previously been a lawyer.

He is regarded as being the founder of the traditional English novel. His most famous book was Tom Jones, which was published in 1749, and no doubt his earthy humour and satire helped in his challenging role of a magistrate. He also became a playwright, but his political satire was considered so vicious a law was passed banning his plays from the London stage.

Back then, magistrates were not funded by the government but by the people who came before them in court. Fielding wanted to change the corrupt system, so he started letting the public in to see the court cases, and he published a newspaper called The Covent Garden Journal, which featured accounts from the court.

In the summer of 1749, crime within the area had rocketed to unprecedented levels, much of it caused by the problems of gin consumption: Fielding recorded that at the time every fourth house in Covent Garden was a gin shop and in Bow Street alone there were said to be twelve pubs or gin dens, as well as numerous brothels. His response was to create the Bow Street Runners (due to their scarlet waistcoats they were originally nicknamed the ‘Robin Redbreasts’ but soon became known as the ‘Bow Street Runners’). They were the forebears of the modern police service that came about a century later.

He brought together eight constables of an honest and reliable nature, whose role was to try to deal with the astonishing levels of crime that was occurring in London by this time. (They may well have started off being ‘honest and reliable’ but, by all accounts, they soon became as corrupt as the criminals they were trying to arrest.) When Henry Fielding’s health deteriorated (gout and cirrhosis), he went to Lisbon, where he died.

He was succeeded as magistrate in 1754 by his blind half-brother Sir John Fielding. Known as the ‘Blind Beak of Bow Street’, Sir John can be credited with refining Henry’s patrol into the first full-time, salaried and effective police force; by 1800 there were 68 trained Bow Street Runners. And even though he was blind, he was said to be able to identify the voices of over 3,000 criminals.

He was certainly a busy man, for at the same time as serving as magistrates and setting up the Runners, he worked to reform the corrupt and ineffectual magistracy system.

A description of Sir John’s time as magistrate appears in the memoirs of Giacomo Casanova, the famous Italian lover, who had been accused of intending ‘grievous bodily harm to the person of a pretty girl’. Casanova wrote, “I went into the hall of justice and all eyes were at once attracted towards me; my silks and satins appeared to them the height of impertinence. At the end of the room I saw a gentleman sitting in an armchair and concluded him to be my judge. I was right, and the judge was blind. He wore a broad band round his head, passing over his eyes. He spoke to me in excellent Italian, saying ‘Signor Casanova, be kind enough to step forward, I want to speak to you’.”

Blind Jack then released Casanova on the surety of two householders that he would not commit such a crime again.

In his early days Charles Dickens was a crime reporter and a regular visitor to the Bow Street courts. He wrote of it, “There were other prisoners, boys of 10, as hardened in vice as men of 50; a household vagrant going joyfully to prison as a place of food and shelter, handcuffed to a man whose prospects were ruined, character lost and family rendered destitute by his first offence.”

Most of the cases heard by the magistrates in the court were of a petty nature, committed by the “sad, ill and unfortunate.”

One of the more famous cases was in 1895, when Oscar Wilde was tried in Bow Street for gross indecency. Upon his arrest, he was “thrown into a cell where he was allowed the luxury of a rug, and the following morning he ordered a breakfast of tea, toast and eggs from the Tavistock Hotel, which were brought across to him on a tray.”

An amusing appearance was that of Tommy Earp, who later became a well-known art critic. He appeared before the court for being drunk and disorderly, having spent the night in an enormous basket of strawberries in the nearby Covent Garden. When asked by the magistrate why he’d climbed into the basket, Earp replied, in a rather exaggerated upper-class accent, “For valetudinarian reasons, purely valetudinarian reasons.” (For those like me who have to look the word up, it means ‘showing undue concern about one’s health’.) The astonished magistrate exclaimed, “Don’t address me as if you were the President of the Oxford Union”. To which Earp replied, “I am!” And he was!

Several cases against authors have taken place here. One was in 1915, when the Bow Street magistrates found The Rainbow, a book by DH Lawrence, to be obscene. Another book that was found to contain ‘acts of the most horrible, unnatural and disgusting obscenity’ was Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness. It was eventually published some twenty years later.

It was hardly surprising that Charles Dickens used the Bow Street court in two of his books. One in particular was Oliver Twist, which he wrote in 1839, where Oliver appears before the magistrates accused of stealing a handkerchief from a gentleman’s pocket. And then a little later the Artful Dodger is there accused of the theft of a jewellery box.

The courts close …

Tim Workman, the last serving Chief Magistrate when Bow Street courts closed, said, “It was the enormous variety that made Bow Street Court so interesting. From drunks in Covent Garden to mass murderers wanted by their home country appearing before you in court, you never knew what to expect.”

He added that whilst he accepted that Bow Street was no longer suitable for the 21st Century, he, like his staff, were sad to have said goodbye to the old court.

It certainly must have been quite remarkable inside. The chief magistrate’s room was ‘imposingly large’, with two dark marble fireplaces standing sentinel at either end of the room. Above one, with a print of Blind Jack Fielding in the centre, a board lists the 32 chief magistrates before Senior District Judge Workman.

And a comment from a former police officer, who added during an interview with the BBC, “The court was always busy and had a special atmosphere and commanded respect with officers turning out in their smartest uniform and even defendants making the effort.”

Last word though to Frederick, a 76 year-old self-confessed burglar, who added he had first seen the inside of the courts in the late 1940s. He described it as being like a railway station, with the bustle of police, lawyers, vagrants and prostitutes.

Other ‘defenders of the peace and law’

These weren’t the only men trying to keep the peace and reduce crime in London. By 1822 in the City of London, the other inner districts and suburbs, there were around 3,680 ‘Parish peace officers of one kind or another’. Some 133 were beadles, paid parish officers with administrative functions, as well as 400 constables, elected or selected by rote from the rate list to serve for a year at a time and act free of charge. Finally, there were also some 2,800 watchmen, called ‘Charlies’, armed with staves and rattles.

Later, Robert Peel would bring all this together – the beginning of the modern police force we know today.

ROYAL OPERA HOUSE

The building you see today is the third theatre on this site. The original, known as the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, opened in 1732.

It was one of only two theatres in London licensed by Charles II to present both spoken word and music performances, the latter being what it became most famous for. One licence was given to the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, whilst the other was given to Sir William Davenant to build a theatre in Covent Garden.

However, although Davenant had received the royal patent in 1662 for theatre, he didn’t do anything about building it, and it wasn’t until actor and manager John Rich (known for introducing pantomime to the British stage) bought the patent that construction began.

To do so, he had used some of the enormous profit he had made staging John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera* at Lincoln’s Inn Theatre in 1728. He had been given a three-quarter share of the theatre by his father – and it was said that the opera ‘made Rich gay, and Gay rich’. I will also mention that Rich was famous at the time for staging what were regarded as new theatrical styles of entertainment, particularly those based on an Italian theme, known now as pantomimes. He often played the part of Harlequin and was famous for his miming ability.

Rich was keen to upstage the nearby Theatre Royal Drury Lane and commissioned prominent architect Edward Shepherd to build the new theatre, which he did in fine Georgian style. And when the Theatre Royal Covent Garden opened in 1732, it was said to be the most luxurious in London, though I doubt whether it had much competition for this title.

Ballet and opera have played a predominant role in the theatre’s success since it opened. In 1734 the French dancer Marie Sallé, performed a new dance called Pygmalion, said to have been the first ballet d’action ever presented on the stage in England.

The first director of music was George Frideric Handel, and the first ever performance of the Messiah took place in 1743. Handel then wrote several other operas specifically for Covent Garden. These included Samson, Judas Maccabaeus and Theodora. He continued to give regular performances until his death in 1759.

Destroyed by fire in 1808

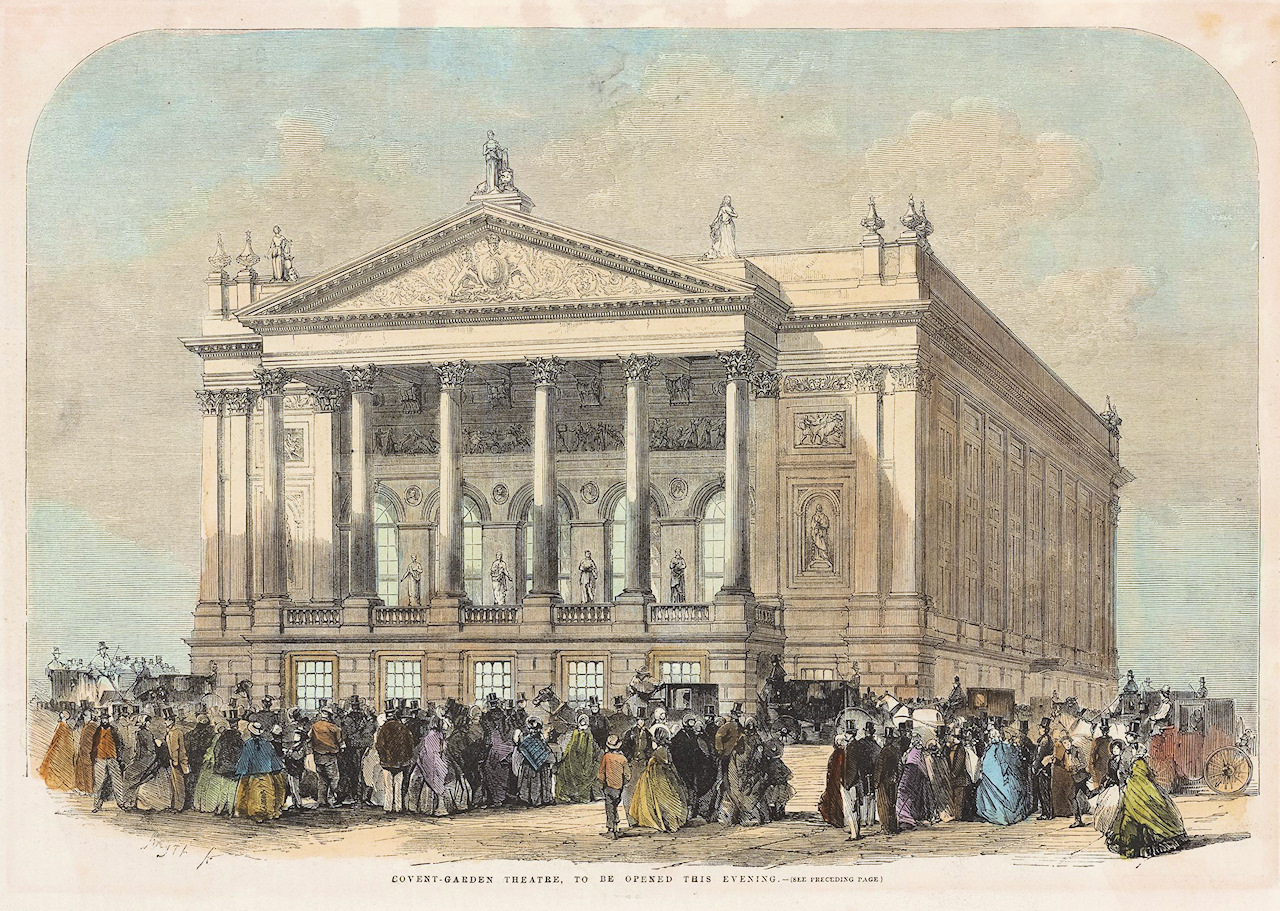

The first theatre burnt down in 1808 in a blaze which killed over twenty firemen, and destroyed most of Handel’s original manuscripts, as well as the organ he had bequeathed. The new theatre opened in 1809 (how come it takes us so long to build anything these days?) and was modelled on the Temple of Minerva in Athens, with a frieze of literary figures under the portico.

The first ever performance in England of Mozart’s Don Giovanni took place here in 1817, followed by Rossini’s The Barber of Seville in 1818 and Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro in 1819.

As an aside, the theatrical expression ‘in the limelight’ came as a result of new ‘calcium oxide’ lighting being installed in the Covent Garden Opera House in 1837. (An intense illumination is created when a flame fed by oxygen and hydrogen is directed at a cylinder of quicklime).

The theatre became known as the ‘Royal Italian Opera’ in 1847 when the Italian composer Giuseppe Persiani bought the lease after the Her Majesty’s Theatre had refused to stage one of his works. He also brought with him many of the singers, and after carrying out various renovations to the theatre, he staged the first English performances of Verdi’s Rigoletto and Il trovatore. However, Persiani’s productions weren’t a success, and ‘Italian’ was dropped from the name, though the repertoire continued to be mainly Italian opera.

A second fire in 1856

Another major fire destroyed the building in 1856, and a new building in the neo-Palladian style was opened in 1858. Shown in the engraving above, taken from the Illustrated London News, it was designed by the 26-year-old Edward M. Barry, the son of Sir Charles Barry, who had designed the new Palace of Westminster after its predecessor had also been destroyed by fire.

The theatre closed down during the First World War and was requisitioned as a furniture repository, reopening in 1919. During the period 1933, up until its closure again at the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Sir Thomas Beecham** became the artistic director and conductor. Unfortunately, whilst his artistic ability was highly praised, it wasn’t financially successful.

During the Second World War the theatre was used as a dance hall, and when it reopened, and thanks to a post-war decision to allow public subsidy of the arts, it became not only the year-round home of the opera company, but the Sadler’s Wells Ballet Company was invited to form the Covent Garden Ballet Company. Later both were able to add the word ‘Royal’ to their titles, so are now known as the Royal Opera Company and the Royal Ballet Company.

At the reopening after the Second World War, the ballet company gave a performance of The Sleeping Beauty, followed by a combined performance with the opera company of The Fairy Queen. Shortly after, the Opera Company’s first individual performance took place, which was Bizet’s Carmen.

A major reconstruction in 1995

In 1995 a £213 million reconstruction project took place, which helped stabilise the fabric of the building and extended it as far as the corner of James Street and Floral Street.

The amazing glass ceiling and barrelled roof of the Floral Hall was restored (it’s worth going inside the main Drury Lane entrance to see it) … and from here an escalator leads to the Amphitheatre bar – the biggest of its kind in London, seating 250. New seating, lighting and air conditioning were installed, together with new dressing rooms, ballet studios, offices and workshops. The enlarged ‘behind the scenes’ space now enables six production sets to be built and moved about on automatic ‘stage wagons’.

A further project took place in 2014 when the foyer and entrances were made more attractive and accessible.

The theatre currently seats just over 2,200 people. I can fully recommend the guided tours that are available. You see so much ‘behind the scenes’ of the theatre and learn more of its remarkable history. There’s an excellent gift shop, café, bar and restaurant.

Oh, and something to be aware of if you visit – the theatre is said to be haunted. During the building works in 1999, workers reported being struck by unexplained flying debris!

Gay drew his characters from real-life criminals. His antihero Macheath was based on the thief and bigamist Jack Sheppard, whose multiple partners and four prison escapes fascinated the public. Crime boss Peachum represented the underworld kingpin Jonathan Wild, who publicly sold goods his gangs had stolen, sometimes back to their original owners. Gay took the name of Jenny Diver, who betrays Macheath, from London’s most infamous pickpocket. Polly Peachum and Lucy Lockit, rivals for Macheath’s love, were proxies for the Italian opera stars Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni, who were popularly (but incorrectly) believed to hate each other.

Thanks to Classical-music.com for this information.

** Thomas Beecham is the man we particularly thank today for London’s top-class symphony orchestras. He was the grandson of the founder of the ‘Beecham’s pills’ business, which provided him with the funds he so lavishly spent on his passion for music. He had arrived in London around 1900 to study music but by the end of the decade, and still in his twenties, he had formed two high-quality orchestras, the New Symphony and the Bournemouth Symphony and later the Royal Philharmonic. Beecham introduced English audiences to composers such as Frederick Delius and Richard Strauss. In 1932 he also became artistic director at Covent Garden and was thus reunited with the Beecham Opera Company, which had become the British National Opera Company in 1923 and had been absorbed by Covent Garden in 1929. He founded the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London in 1946 and continued to conduct until 1960.

THE THEATRE ROYAL, DRURY LANE

The theatre we see today is the fourth to have been built on the site, with the earliest dating back to 1663, making it the oldest in London. That first theatre was a three-tiered wooden structure which could accommodate 700 people. To let daylight in there was no roof and performances usually began at 3 pm to take advantage of whatever light there was. A glazed dome was later built over the opening, but according to entries in the diaries of Samuel Pepys, who was a regular visitor, it was not entirely effective at keeping out the elements: he describes how he and his wife were forced to leave the theatre to take refuge from a hailstorm.

In one of his diary entries he wrote, “The house is made with extraordinary good contrivance, and yet hath some faults, as the narrowness of the passages in and out of the pit, and the distance from the stage to the boxes, which I am confident cannot hear; but for all other things it is well, only, above all, the musique being below, and most of it sounding under the very stage, there is no hearing of the basses at all, nor very well of the trebles, which sure must be mended.”

It was around this time that the famous actress Nell Gwynne performed here. She was among the first of the actresses to play on the stage and was praised by Samuel Pepys for her comic performances (he called her ‘pretty, witty Nellie’). She caught the eye of Charles II, who used to visit often, and of course she later became his mistress and had two sons by him.

Though it escaped the Great Fire of London (which never reached this far west), it burned down in 1672, and two years later a new, larger theatre was built on the site by Christopher Wren.

This building lasted for nearly 120 years, during which time the first ever ballet to be performed in England took place. (In case you might be interested, it was called the The Loves of Mars and Venus and was staged in 1717.) And another point of interest: in the year before an assassination attempt was made in the theatre on George II. A few years later, the then musical director composed a song in honour of George’s successor, George III. Called ‘God Bless Our Noble King’, the audience stood at very first performance, a tradition that of course continues to this day.

As a result of the illustrious actor David Garrick purchasing the theatre in 1747, it became a great success. He served as both lead actor and manager for some twenty years. Garrick was said to have been one of the finest ever stage actors, especially remembered for his role in promoting Shakespeare on the English stage as well as introducing a “realistic, naturalistic style of acting, abandoning the artificial bombast typical of dramatic roles previously.” Some twenty-four Shakespeare plays were performed here during his time. This was probably helped by the shortage of new plays, which arose because an Act of Parliament of 1737 required the government to authorise and licence any new play before it could be staged. Garrick continued as manager for some years after he retired from the stage.

By the end of the 18th century, it needed refurbishing and was demolished in 1791, with a new, much larger theatre accommodating 3,600 people opening in 1794. It was said to have then been the largest theatre in Europe and except for the churches, one of the tallest buildings in England. However, it was so large it made it difficult for people to hear the actors’ voices, so productions began to feature ‘spectacles’ with less spoken word. Such spectacles included water features – a stream flowing over rocks and tumbling down into a ‘lake’ on which a life-size boat was rowed across the stage. Real water was used, which was kept in huge tanks above.

And I will just add that another royal assassination attempt was made in 1800, when George III was shot at by a lone gunman – during the singing of the new national anthem – but fortunately the gunman missed.

Sadly, this new theatre lasted just 15 years and in 1809 was destroyed again by fire. The blaze was watched by Richard Sheridan, who had managed the theatre and invested a considerable sum of money in it, whilst he sat in the nearby Great Piazza Coffee House. When a fellow customer commented on Sheridan’s calmness at watching such a disastrous event, Sheridan apparently replied, “Can’t a fellow enjoy a drink by his own fireside?”

Another theatre was built on the site, opening in 1812; it is shown in the engraving above. Although the number of seats was reduced by around 500, it still accommodated 3,000. Much of this theatre is the one we see today. Though it reopened with a performance of Hamlet, the idea of ‘theatrical spectacles’ did continue. A major breakthrough took place in 1817, when it was one of the earliest theatres in Britain to be gaslit throughout. In 1820 the portico, which still stands at the front entrance to the theatre, was built, and several years later the colonnade that runs down the Russell Street side was added, making it more pleasant for those queuing for admittance.

The theatre’s popularity increased significantly in 1879 when Augustus Harris took over (we saw his memorial outside). He was responsible for introducing one of the theatre’s major draws which were the Christmas pantomimes. These played to packed houses and would often run until the end of March. He also continued with the idea of the theatrical spectacles – one of which was a play called The Whip, which included a train crash and a live recreation of a horse race, with twelve horses racing on stage (thanks to a treadmill).

A major renovation took place in 1922, after which one of its big draws was the composer and performer Ivor Novello. Since the Second World War, the theatre has primarily put on long running musicals, which have included Oklahoma!, The King and I, My Fair Lady, 42nd Street and Miss Saigon.

In 2000 the theatre was purchased by Andrew Lloyd-Webber who, to mark its 350th anniversary in 2013, began a £4 million restoration. This returned some of the original features of the theatre to their Regency style.

For those particularly interested in this wonderful theatre, I can thoroughly recommend their backstage tours, which need to be booked in advance.

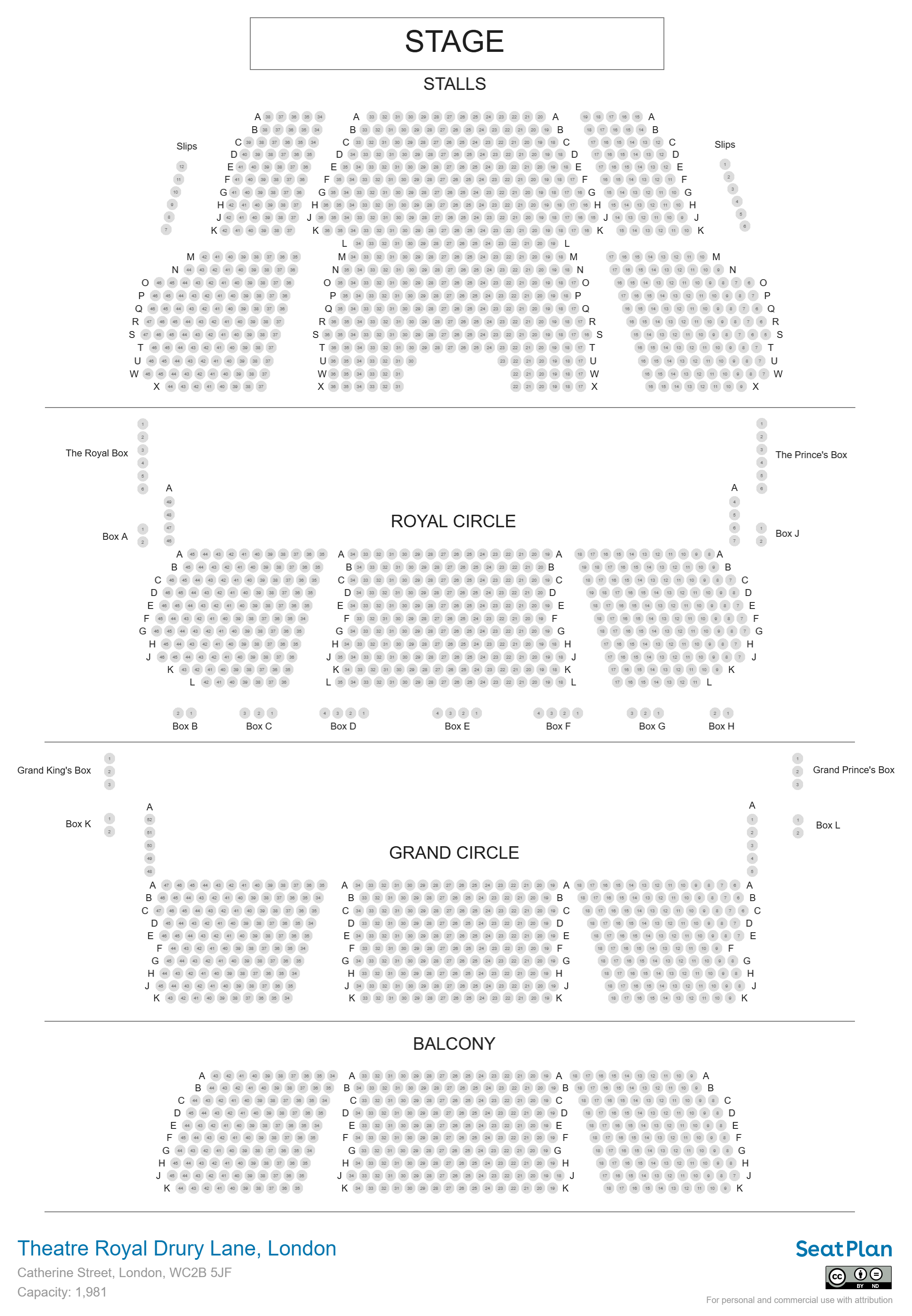

Its present seating capacity is 2,154 according to the theatre’s own website but several others, including Wikipedia, say 2,196 – while SeatPlan.com reckons it’s not quite two thousand.

Click to view full interactive Theatre Royal Drury Lane seating plan

Click to view full interactive Theatre Royal Drury Lane seating plan