Updated: 13 March 2021 |

|

Walk page: Click to view |

Appendix to the Isle of Dogs walk

MORE ABOUT THE ISLE OF DOGS, PAST AND PRESENT

The history of the Isle of Dogs and its docks, the development of Canary Wharf, and the troubled story of the SS Great Eastern.

THE DRAMATICALLY CHANGING FORTUNES OF THE ISLE OF DOGS

The changes in the fortunes of the Isle of Dogs have certainly been dramatic. For hundreds of years this was an area of isolated and inhospitable wetlands known as the Stebenhethe (Stepney) Marsh. The only known dwelling was Chapel House, thought to have been named after a medieval chapel called the ‘Chapel of St Mary’. It was located next to a track used by pilgrims travelling from Walthamstow Abbey to Canterbury, who would then cross the Thames to Greenwich via a primitive ferry from where the Island Gardens are today.

The area had always been badly affected by flooding caused by high tides, which was why there were so few inhabitants, and although efforts had been made for some years to try and prevent the worst of the flooding in order to make it more usable for farming, particularly the grazing sheep and cattle, it wasn’t until the 17th century that they began to have more success. This was principally because of the help given by Dutch engineers, who of course already had considerable experience of dealing with draining low-lying land in Holland.

They began to improve the rudimentary walls on the banks, dig ditches and build windmills to pump excess flood water back into the river, but despite this few people continued to live there.

However, by 1802 it was all change! The open countryside was replaced by the massive docks which were built to cope with the phenomenal increase in trade between London and the rest of the world. Until this time, ships used to unload and load their cargoes at quaysides built along the banks of the River Thames in the centre of London, but as trade grew and despite the quaysides being extended for miles downriver through Wapping and Limehouse, there still wasn’t sufficient room. Ships were forced to moor in the middle of the river and unload into smaller boats which would carry the cargo ashore. This led to long delays – sometimes even many months – whilst waiting to be able to unload. And this also resulted in pilfering on a massive scale – up to a third of all goods ‘disappeared’, either from the ships themselves or from the quaysides.

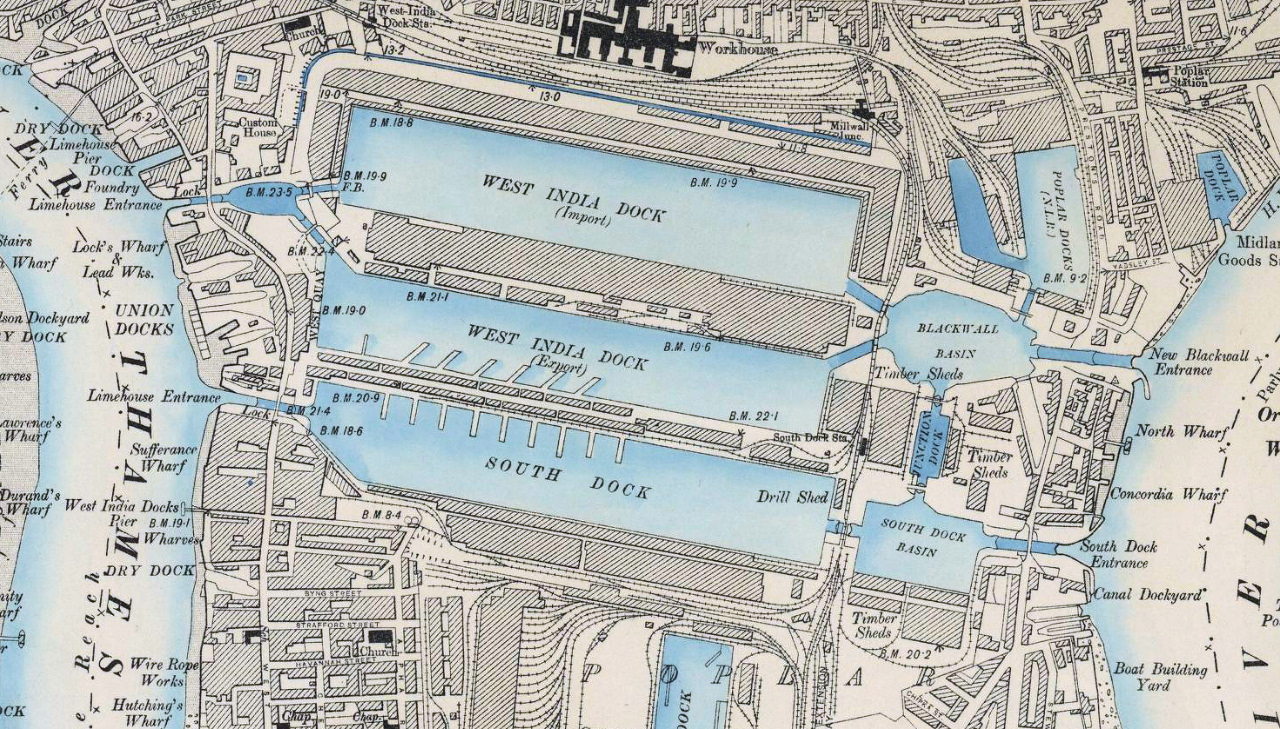

Shipowners and merchants combined to build the first ‘secure dock’ on the Isle of Dogs. Surrounded by enormous and formidable looking high walls and manned gates they were an instant success. Initially two huge ‘dock basins’ were built – the West India Dock, so named because its trade was with the West Indies, had two basins, one used for imports and the other for exports. Thousands of ships would arrive here each year, bringing cargoes of sugar, rum, timber and exotic fruits.

As they became ever busier, further expansion took place with the opening of the massive Millwall Docks and then the East India Docks complex.

All of this meant employment for many thousands, and from a population of less than a hundred at the beginning of the 19th century, it had risen to over 20,000 by the start of the 20th.

However, the Second World War had a major impact on London’s docks and its associated factories as they were amongst the top targets for the German Luftwaffe. At one stage there were bombing raids for seventy-six consecutive nights. Huge numbers of quayside warehouses, factories and thousands of people’s homes were destroyed.

Once hostilities ended rapid reconstruction soon got under way and business began to boom once more, but this revival was short-lived. The introduction of ever larger ships and then containerisation, combined with constant labour difficulties, meant that by the 1960s and 70s shipping had begun moving to the new, larger and better equipped container ports such as Tilbury, Felixstowe and Southampton. The decline of the docks was nearly as rapid as its initial growth and it wasn’t long before they began to close. And it wasn’t just the docks; many of the associated industries and businesses also closed. The result was abandoned warehouses, derelict factories and very little work for the local people.

‘The Forgotten Island’

It soon became the ‘Forgotten Island’ and by 1981 the population of the Isle of Dogs had dropped to 15,000. However, shortly after, the Conservative government, led at the time by Margaret Thatcher, helped form the London Docklands Development Corporation (known as the LDDC). Its aim was the regenerating of some 8 ½ square miles of not just the docklands, but some of the surrounding areas of the East End of London that had struggled since the end of the Second World War.

As a result, it became an ‘Enterprise Zone’ with tax breaks and freedom from many planning restrictions which led to new businesses being attracted there – everything from finance, for which the area has now become so well known, to printing and distribution companies.

The LDDC created new access into the area with the opening of the East India Dock Tunnel, the Lower Lea Crossing, the Limehouse Link, as well as pedestrian and cycle paths. They did the same with public transport, which had previously consisted of only a few rather limited bus routes, which had made local people feel ‘cut off’ from the rest of London. The opening of the Docklands Light Railway (the DLR) was a vital part of the early successful redevelopment of Isle of Dogs. Transport links improved further when the Jubilee Line was extended to Canary Wharf. The final piece in the transport infrastructure was the opening of the London City Airport in 1987, again another success of the LDDC.

Besides all of this, a considerable amount of money was spent on improving the quantity and quality of social housing, adding new schools, medical centres and community and social facilities.

The result was Canary Wharf becoming one of the world’s leading financial centres, as well as a popular place to both live and visit.

Filling in the docks

I will just add here that there was a major concern in the 1980s when the owners of the docks, (the Port of London Authority and Tower Hamlets Council who were the local authority), decided to fill in the docks rather than keep paying out to maintain them. However, it didn’t take long before these large expanses of water began attracting residential developers and, instead of being filled in, the waterside became a popular place to live and work.

In 1997, the LDDC handed over the responsibility for the Isle of Dogs and surrounding area to Tower Hamlets Council and British Waterways (now the Canal and River Trust) who took over responsibility for the docks themselves.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE DOCKS ON THE ISLE OF DOGS

Since Roman times ships have sailed up the River Thames bringing cargoes from around the world to be unloaded in London. Over the centuries the importance of this trade grew rapidly, and whilst initially there had been plenty of room for ships to unload their cargoes onto the riverside quays in the centre of London, as trade grew this became a major problem.

As a result, ships became forced to anchor in the river and unload their cargoes into barges (known as ‘lighters’ because they were literally lighter than the ships they were unloading). However, this caused all sorts of problems; congestion being one and it was said that at times you could cross from one bank of the Thames to the other simply by stepping from one ship to another. Another problem was the time it was taking for ships to await their turn to unload, sometimes having to wait for as long as two months, which cost the shipping companies a considerable amount of money. The third problem was theft. Up to a third of all goods were said to simply ‘disappear’, again at a huge cost to the ship owners and the merchants who were importing the goods.

By the latter part of the 17th century the situation had become so serious that Parliament authorised the ‘West India Company’ to build an ‘enclosed dock’ on the Isle of Dogs. At the same time they gave them a virtual monopoly in the valuable trade in sugar, rum and spices from the West Indies.

The West India Docks, as they were called, opened in 1802, and they were immediately successful. However, despite its vast size – it could accommodate up to 600 ships – demand began to outstrip supply, so further docks were built. These included the Millwall Docks, also on the Isle of Dogs, and the East India Docks. Other docks were built and eventually this massive network of often interconnected ‘inland harbours’ stretched from St Katharine’s Dock, alongside the Tower of London, all the way down the Thames to Woolwich. The last of these great docks was the enormous ‘Royal Dock’ complex which opened in 1921. And I must just mention that it wasn’t just goods that were being imported – the success of the Industrial Revolution meant that British products needed to be exported across the world.

Nationalisation and the Port of London Authority

The various docks had been built and owned by private companies, but in 1909 they were nationalised and brought under the control of the newly formed Port of London Authority.

Whilst the growth continued through the 1920s and 30s, things changed radically with the outbreak of the Second World War when the docks became a major target for the German bombers. Huge areas were damaged or destroyed – not just the docks themselves, but the warehouses and factories and of course the homes of many thousands of local people as well.

After the war was over, there was a prolonged period of rebuilding and renovation, but within a few years the docks went into decline. There were two major reasons for this; one was the continual labour disputes, whilst the other was the advent of huge container ships. As these ships got bigger, they couldn’t navigate as far up the River Thames as the smaller ships had and so instead were unloading at the new enormous container ports in places like Canvey, Felixstowe and Southampton – and of course on the continent as well.

Eventually the situation became so bad, that one by one the docks closed … and the story resumes with the formation of the London Docklands Development Corporation, to which I’ve referred previously, and then, more specifically, with the development of the Canary Wharf we know today.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF CANARY WHARF

The story behind the development of Canary Wharf goes back to 1984 when the ‘Roux brothers’, who owned the famous Le Gavroche restaurant in Mayfair, were looking for a building in which to prepare and pack pre-cooked meals. Michael Von Clemm, who was chairman of the Roux company (and was also Chairman of the Credit Suisse and First Boston banks), was invited by the newly formed London Docks Development Corporation to a lunch on a Thames barge which was moored close to one of the derelict warehouses on the Isle of Dogs. They were meeting to see whether these warehouses could be suitable for the project they had in mind. Over lunch Von Clemm said that they reminded him of the warehouses in Boston Harbour, which had been converted into offices. He discussed the idea of replicating some of what had been done in Boston on the Isle of Dogs with his colleague G. Ware Travelstead, who was his property advisor.

Travelstead had grown up on a farm in Kentucky with a father who was both an engineer and businessman and involved in the construction of a number of iconic buildings in America, such as the World Trade Centre and Cape Kennedy. His son seemingly had the same flair and became a successful property developer in his own right. He could see the potential for a financial services development on what was by then the derelict West India Docks site and played a leading role in persuading both the new London Docks Development Corporation (LDDC), and the government to approve his scheme. Indeed, both Michael Heseltine, the Environment Secretary and Prime Minister Maggie Thatcher supported his scheme to build three 850 feet high tower blocks on a site of around ten million square feet in the centre of Canary Wharf. Today it is known as One Canada Square with Number One at its centre.

All was looking good until the financial backers decided against funding the project and so despite all that Travelstead had already achieved, he was forced to pull out of the scheme.

As it turned out, Olympia & York, a Canadian property company, had already sent one of their staff, George Iacobescu, a Romanian born engineer, to the London docklands to look for potential development sites in which they could invest. In little more than a month, the company took on the project. Which was fine – until they too went out of business!

Olympia & York had kept Travelstead’s proposal of three towers, which they decided to group around a square that was at first to have been called Docklands Square, then Churchill Square, but finally they decided on Canada Square – the name we know it as today.

Problems with transport links

Although building began in 1988, there were numerous problems. Besides the difficulties they had with trade unions, the biggest problem was the very limited access by road to the Canary Wharf site. This though they eventually solved by bringing nearly all the materials needed for the construction by barge up the River Thames from Tilbury. And despite these early problems, the Canada Square development opened just three years later!

Unfortunately, this wasn’t the end of the difficulties, as it coincided with the beginning of a financial recession which meant it was difficult to find new tenants for the buildings and they remained empty for some time.

I think it’s worth mentioning that despite Travelstead’s failure to proceed with his grand vision for Canary Wharf, he certainly wasn’t put off becoming involved in other major developments. He was a key player in the development of the run-down port of Barcelona, which resulted in it becoming ‘Port Olympico’, a major feature of the 1992 Olympic Games.

The architect of One Canada Square

The architect who Olympic & York chose to create the design for Canary Wharf’s iconic central building – ‘One Canada Wharf’– was César Pelli, the famous American-Argentinean architect who had already designed a number of iconic buildings across the world. These included the World Trade Centre in New York and the Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, which for many years was the tallest building in the world. On a different level he had also received significant acclamation for the restoration and expansion of the famous Museum of Modern Art in New York.

César said he based the design of One Canada Square on a combination of the World Trade Centre in New York and Big Ben in London (or to use its official name, the Elizabeth Tower).

He said he chose the stainless-steel cladding, with its ‘linen finish’ because it seemed to ‘suit the soft foggy light and atmosphere of London’. (By which he presumably meant it would stand out, even in the misty weather that can affect this part of the Thames. And presumably another reason for him choosing the illuminated ‘pyramid roof’).

Although César continued to use Travelstead’s original plans for a building 850 feet high, he had to reduce it by 26 feet due to concerns about it being on the flight path of the newly opened London City Airport nearby. Despite this reduction, the company who were developing it said they still wanted the same amount of office space and insisted that the building’s width should be increased to compensate. This meant it was not quite the tall and slender building that César had wanted, so he suggested building more subterranean floors beneath ground level. The developers refused this as the rental value of those floors would have been much less. However, a compromise was eventually reached.

“Not quite stunning”

The final result was a building was that wasn’t universally liked, at first anyway. Prime Minister Maggie Thatcher commented, perhaps almost tactfully, that maybe the building “was not quite stunning”, whilst Prince Charles was said to have commented, in his more forthright manner, that he would personally go mad if he had to work in somewhere like that.

And interestingly, after Olympia & York pulled out of the development due to financial problems – they eventually went bankrupt. However, just three years later, in 1995, a spin-off of the original company called Olympia & York Properties, became part of a consortium that purchased the Canada Wharf Estate.

More on One Canada Square … the pyramid roof

A prominent feature of the building is its illuminated 130-foot-high stainless-steel pyramid roof. It weighs over 100 tons and contains maintenance equipment and water tanks for both general supply and the washing of windows. (The building uses 200,000 gallons of water a day, whilst 426,000 gallons of water are needed to clean the entire tower). The pyramid itself is cleaned manually by specialists who abseil down from the very top.

The roof can be seen from as far as 20 miles away, depending of course on the weather. There are a thousand electronically controlled, energy efficient fluorescent tubes that can be programmed to produce a multitude of different sequences for special occasions. On the very top is a flashing aircraft beacon that acts as a warning to aircraft approaching London City Airport.

The continuing development of Canary Wharf

The development of high-rise buildings in Canary Wharf and the Isle of Dogs has shown no signs of abating. Whilst the buildings were at first for commercial use, this has more recently changed and now many are for residential purposes.

Tallest of these is the 771-foot-high ‘Spire London’, said to be the highest residential tower in Western Europe. It has 861 flats and three roof-top duplex penthouses with outside terraces. All residents are said to be able to enjoy an infinity pool on the 35th floor, spa, a jacuzzi, private cinema and a ‘sky high cocktail bar’. And when you see it, I’ll just mention that its petal shaped design is apparently inspired by ‘the nautical history of the site and the Chinese orchid’. So now you know! (And if you are interested in living there, I have no idea how much the penthouse suites cost, but at the time of writing a one-bedroomed flat starts at £625,000. And a sign of the times … the building only has nine parking spaces!)

Nearby is another almost equally high and impressive apartment building, the 760 feet high Landmark Pinnacle, which you also pass on the walk.

And whilst both are nearly the same height as One Canada Square, which for a few years was Britain’s tallest building, they are a long way off the Shard, still Europe’s tallest, at 1,100 feet.

Security at Canary Wharf

When visiting Canary Wharf you will notice the considerable numbers of security staff who patrol the estate. Not only that, but there are security gates at all vehicle entrances, together with ramps and bollards that can quickly be activated to prevent vehicle access. During periods of heightened security, every vehicle has to stop and be checked, with security staff looking both inside and, by the use of mirrors on long poles, underneath as well. This is because in the past bombs have been fitted to the underside of vehicles.

These security procedures were initially introduced in response to the numerous IRA terrorist bomb attacks on the City of London and elsewhere in Britain. Indeed in November 1992, shortly after One Canada Wharf opened, terrorists parked a vehicle containing high-explosives close to the building, but as the bombers were about to escape, security guards approached the vehicle because it was illegally parked on double lines. The bombers pointed a gun at the guards, but it failed to fire and they managed to escape. Bomb disposal squads were quickly at the scene, but fortunately the detonator failed to explode so there was no damage. High security within the Canary Wharf complex has remained in place since then.

However, just five years later in 1996, the Provisional IRA did manage to detonate a bomb at the nearby South Quay. This was just outside of the Canary Wharf estate and so not covered by its security network. Two people were killed and there was considerable damage.

There was another major security scare following the attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York on the 11th September 2001 and several of the skyscraper office blocks were evacuated as a precaution.

In the event of a fire …

Obviously, a building of this height needs the most up to date precautions and technology in order to be able to cope with the risk of fire. It was designed so that in the event of a fire alarm the whole building does not need to be immediately evacuated. All floors receive details of a fire alarm, but the system is programmed to display messages on each floor indicating its specific level of risk.

The floor where fire has been detected, together with those above it, are evacuated first. The air-conditioning is put into reverse – extracting the smoke and then bringing air in from the outside into the fire escape passages and stairs. Video cameras are installed throughout the building which will look for a fire and detect any other abnormalities.

Swaying in the wind …

It’s a fascinating fact, but a building of this height has to be designed to sway in high winds. To offset such movement – which can be up to 13 inches – it has a steel pendulum that acts as a ‘tuned mass damper’, which according to Wikipedia is a device ‘mounted in structures to reduce the amplitude of mechanical vibrations’. So now you know!

CANARY WHARF IN NUMBERS

- There are 16.5 million square feet of office and retail space in Canary Wharf.

- 120,000 people work in Canary Wharf.

- The average annual salary for a worker in Canary Wharf is £100,000 – one of the highest in Britain.

- Around 72,000 people travel into Canary Wharf on the Jubilee Line each day.

- There are five shopping malls with around 300 shops, restaurants and bars in Canary Wharf.

- It has ‘its own’ international airport – London City Airport – just a couple of miles away.

- Nearly 50 million people visit Canary Wharf each year.

- Canary Wharf has 20 acres of outdoor space.

- The 97-acre site is owned by the Canary Wharf Group, which in turn is owned by a Canadian property company and the Qatar Investment Authority who bought it for £2.6 billion in 2015.

- The HSBC building was sold for a record £1.1 billion when property prices were at their peak in 2007.

- Over 200 art and other events are held in Canary Wharf each year – many free to attend.

- It’s renowned for its award-winning public art installations, one of the largest in the UK, with over 70 individual pieces.

- Canary Wharf is home to the largest Waitrose store in Britain – complete with a temperature-controlled wine cellar, stocking over 2,000 different wines from 20 different countries, with regular tastings available.

- Canary Wharf’s Jubilee line underground station is the second busiest in London. Twenty escalators cope with up to 50,000 travellers a day – 40 million a year!

THE LEVIATHAN (LATER RENAMED THE GREAT EASTERN)

I have written quite a bit about the ship in the walk’s commentary but as it such a fascinating story I’ve added more here.

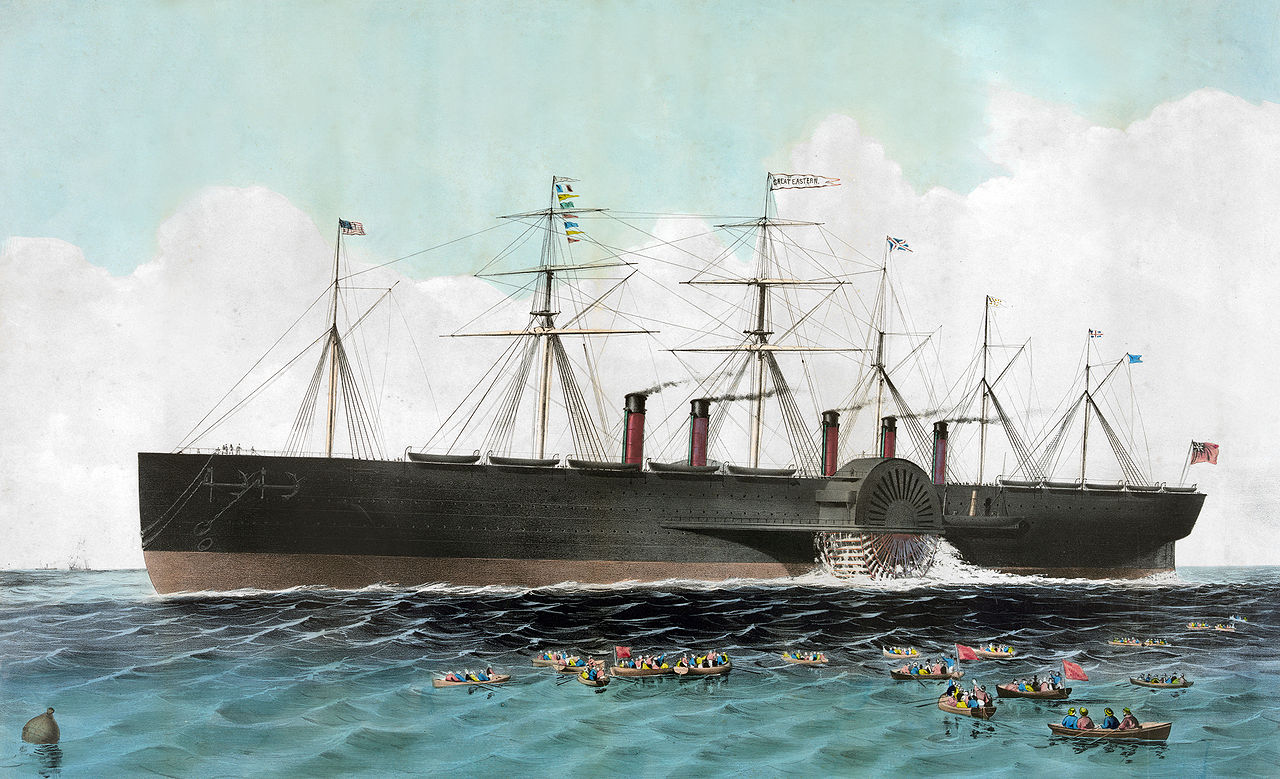

Work had begun on what was to be the world’s largest ship in 1854. It was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who had already built two huge steamships, the Great Western and the Great Britain and this one was to be even bigger and better. He worked in conjunction with John Scott Russell, who had acquired the shipyard on the Isle of Dogs in 1848.

The ship was being built for the Eastern Steam Navigation Company, who wanted to exploit the growing trade with Australia. At that time ships would have to stop several times en route to take on coal, which besides making voyages even longer, the cost of shipping coal out to these ‘coal bunkering stations’ and maintaining them was very expensive.

To avoid this, Brunel designed the ship so it could carry considerably more coal and eliminate the need for the refuelling stops, whilst also accommodating even more passengers (4,000) and additional cargo.

The ship was 680 feet long, with a revolutionary double-skinned hull and propelled by paddles and a single screw propeller, whilst still having six masts with sails. Weighing 19,000 tons with a displacement of 2,500 tons it was designed to travel at 14 knots per hour. However, the cost of building it was almost one million pounds – a staggering sum in the 19th century!

Unfortunately, there were problems from the very beginning, some due to the many advanced technical innovations that Brunel wanted incorporated, and as a result, the shipyard building it went bankrupt. Brunel himself also suffered severe financial difficulties and it was thought that the ship would never be completed.

However, work did continue, and the ship was finally ready to launch in 1858, four years after building had started. As I’ve explained in the walk commentary there were considerable problems with the launch, but other things continued to go wrong too. For example, two days prior to its eventual maiden voyage in 1859, Brunel had a stroke and sadly he died ten days later at the age of just fifty-three. And during that first voyage an explosion on board killed five of the crew.

The misfortunes got worse. The Great Eastern never got to sail to Australia, instead just making several voyages to America. On the first there were only thirty-five paying passengers on board, whilst even on the second there were only one hundred. On its third voyage a storm hit the ship, resulting in both paddle wheels being lost and the rudder made useless.

It never carried passengers again and was used instead to lay the first transatlantic telegraph cables. However, her end wasn’t far away. She sailed to Liverpool in 1886 where she was firstly used as a floating circus and funfair, before then being used to sail up and down the Mersey displaying large banners advertising a Liverpool department store. Her demise came just four years later, when in 1890 she was finally broken up and used for scrap. A very sad end in many ways to Brunel’s amazing career and an equally amazing ship.

And it was another forty years before another ship was built that was bigger than the Great Eastern.

Finally, I’ll just mention that this was the last ship of any significant size to be built on the Isle of Dogs, although other shipyards continued building smaller warships for another fifty years or so.

If you would like more information on the Great Eastern, including reading more about many additional misfortunes that occurred, then I suggest you look at its Wikipedia page.

RIVER THAMES WATER QUALITY

As you walk around the Isle of Dogs and look at the brown-coloured River Thames, you might think that it is still the dirty river it always was.

However, that definitely isn’t the case! The tidal River Thames is now cleaner than it has been at any time over the past couple of hundred years and considered to be one of the cleanest city rivers in Europe. And that brown colour – it’s simply due to the natural mud in the estuary and not pollution.

ART IN CANARY WHARF

As you have walked through Canary Wharf, I have mentioned several pieces of sculpture. However, in total there are over seventy art installations throughout the estate, and if you’d like to know more then I suggest you take a look at this page on the Canary Wharf Group’s website.