Updated: 28 June 2022 |

|

Walk page: Click to view |

Appendix to the Soho walk

MORE INFORMATION ON SOHO

Soho is London’s most cosmopolitan and diverse area. It’s got a fascinating history and there is something of interest every few steps, all packed into such a relatively small space.

Geographically, what makes Soho?

Unlike many areas of London, it’s got quite distinct boundaries so it’s easy to define. Oxford Street marks the northernmost point, whilst to the west it is Regent Street, which separates it from the more upmarket Mayfair. To the east it is Charing Cross Road, which separates it from Covent Garden, whilst to the south …. well, to some people it is Shaftesbury Avenue, but I consider Chinatown to be part of Soho, so it would be the line of Coventry Street, which runs from Piccadilly Circus to Leicester Square.

SOHO’S HISTORY

In the Middle Ages this was just open countryside and farmland, owned, for some strange historical reason, by the Abbot and Convent of Abingdon and the Hospital of Burton St Lazar in Leicestershire. The Dissolution of the Monasteries meant this land was taken by King Henry VIII to be used as hunting grounds for his Palace in Whitehall. Indeed, the name ‘Soho’ was an old hunting cry. The name must have passed into common usage by the 17th century as a survey carried out in 1650 mentions a ‘highway leading from Charing Cross towards So Hoe’. Parts of the land were later sold, leased or granted to various Earls, including those of Salisbury, Newport, Portland and Leicester.

The area began to be developed by the wealthy landowners in the mid-17th century, not long after the Great Fire of London which had destroyed two-thirds of the city and left almost 100,000 people homeless. Indeed, much of Soho was built in the years between 1666 and 1740. There are still a number of early 18th century houses, as well as some that were built in the mid to late 18th century in Soho today.

The first residents were the wealthy aristocratic gentry who built their rather grand houses in Golden Square and Soho Square. Around the same time, less expensive houses were being built elsewhere in Soho for the ‘lower classes’, particularly for tradesmen, artisans and shopkeepers, some with their workshops, storerooms or shops on the ground floor with living accommodation above. Many were built by different property speculators and builders, often with sub-standard workmanship and materials. Within a few decades they were in poor condition.

However, the wealthy and aristocratic didn’t stay long; unhappy with the sort of ‘common people’ coming into the area. They began moving slightly west into the posher Mayfair, just across Regent Street, which was built in 1823, dividing it from Soho. Some of the houses they left were demolished with smaller ones built in their place, whilst others were sub-divided into smaller houses and apartments. This was already happening as early as the late 1700s, but the last straw would have been the major outbreaks of cholera in Soho in 1850. At the same time, many more immigrants, needing cheap accommodation that the area offered, began moving in.

Soho and immigration

The biggest change in Soho was as a result of immigration. London has always been a safe haven for immigrants fleeing political, religious and economic turmoil and there was certainly plenty of that going on in Europe around this time. Initially in countries such as Greece, where many came following the Ottoman invasion of their homeland in the 1670s.

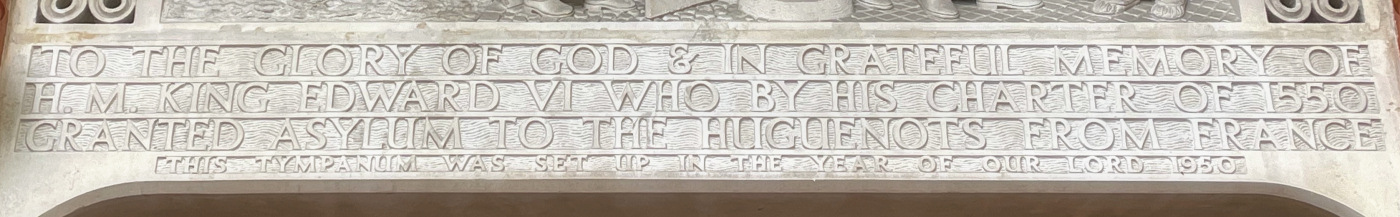

Soon after, large numbers of Huguenots began arriving from France, Holland and what we term today the ‘Low Countries’. They were fleeing religious persecution by Catholics who were suppressing the Protestant religion. They settled in many parts of London, such as Spitalfields and Islington, but Soho became particularly popular. Most were skilled artists and artisans who set up businesses such as lacemaking, making gloves, jewellery, shoes and bookbinding, etc. They were attracted to Soho because of the type of accommodation that was available, moving into the houses in the eastern area of Soho, such as Dean, Frith, Wardour and Greek streets, where as I’ve said, many were built with workshops as well as living accommodation. By 1711 the population of the parish of St. Anne’s, which covered the Soho area, was slightly over eight thousand, of which between a quarter and a half were French. Indeed, there were so many French people living in Soho at the time, that a commentator in 1720 wrote, “the abundance of French people, many whereof are voluntary exiles for the religion, live in these streets and lanes, following honest trades; and some Gentry of the same nation”. In 1740, another commentator wrote, “Many parts of this parish so greatly abound with French that it is an easy matter for a stranger to imagine himself in France”.

A few years later, due to political upheavals, failed revolutions and poverty in Europe, many more immigrants began arriving, this time from countries including Russia, Poland, Hungary and Germany, as well as many Italians, particularly from the north of that country. Again, some ended up living in Soho, attracted by the cheap rents and cosmopolitan atmosphere that it offered. However, it was hardly surprising that this led to overcrowding, one of the reasons the 1850 cholera epidemic affected so many people.

In John Galsworthy’s book ‘The Forsyte Saga’, set in the late 19th century, he described Soho as … “untidy, full of Greeks, Ishmaelites, cats, Italians, tomatoes, restaurants, organs, colour stuffs, queer names … it dwells remote from the British Body Politic”. This mix of different nationalities and cultures and its resulting colourful and cosmopolitan atmosphere resulted in it also becoming popular with writers and artists of all kinds, and on the walk we pass some of the pubs where many of them seemed to spend much of their time!

During the early to mid-20th century some of these immigrants began opening cafes and restaurants specialising in the cuisine of their homeland, which further emphasised Soho’s cosmopolitan and somewhat ‘bohemian’ atmosphere.

A research project called ‘Life and Labour in London’, which was undertaken by the social reformer Charles Booth in the late 1890s revealed that much of Soho was ‘populated by many foreigners, French chefs and jewellery men’. He went on to say that in the northern part of Soho (above Shaftesbury Avenue), houses were mixed – some comfortable, some poor. The census, carried out just twenty years later, revealed Wardour Street being home to many immigrants, mentioning in particular those from Russia, Italy and Switzerland. (I have to say I found the latter rather surprising).

Soho in the 20th century

As people moved away from Soho many of its buildings are now used by businesses. A typical example of this is Wardour Street. Soho has for a long time been known for being artistic, creative and with a very diverse population. That led to it becoming known for its entertainment (which I cover shortly). By the 1930s Wardour Street had a reputation for the number of music publishing companies based there, and it soon also became known for being the centre of Britain’s film industry, something we see, and I explain more about in the walk. More recently, Soho has also become the centre for the advertising industry, with many agencies making it their base.

Soho and the arts

Soho has long attracted the artistic community – many famous writers, poets, artists, composers and musicians have lived here over the years. The young 9-year-old Mozart lived here with his father and sister for several years. Hungarian composer Frank Liszt, the painters Canaletto, Constable and the ‘romantic’ Italian painter and adventurer Casanova. Poets and writers William Blake and Percy Shelley have lived here, along with revolutionaries such as Karl Marx.

Cinema

For many years Britain’s film industry has been centred on Soho, particularly around Wardour Street, where many of the major cinema companies have had offices and post-production facilities. (Those of you who can remember the British Board of Film Classification certificate that used to be put up on screen before each and every film was shown in a cinema, may remember it showed its address as being ‘Soho Square, London’).

Music

Soho has been the centre of ‘modern music’ in the UK. From the 1950s onwards, this was the birthplace of British skiffle, jazz and blues. Indeed, Ronnie Scott’s is still one of the country’s premier jazz clubs, with live music virtually every night of the week.

Top bands were recording in local studios and performing in the local clubs. The Rolling Stones, Genesis, David Bowie all recorded some of their best-known albums in Soho.

Soho in the 1960s and 70s certainly was where it all ‘happened’.

Fashion

Soho was where, in the 1950s and 60s, the teenage fashion scene for men kicked off. Carnaby Street in particular became the world centre of young men’s – and shortly after – women’s fashion. It was thanks to one man in particular, John Stephen, and his early mentor Bill Green, that in just five or so years, a very ordinary back street became famous, having major influences on the biggest stars of the day – everyone from Cliff Richard and Billy Fury through to the Rolling Stones, The Who and The Kinks (whose top ten hit ‘Dedicated Follower of Fashion’ was all about Carnaby Street and its young male clientele. I find it so fascinating that I’ve written a separate section below about it.)

Soho’s nightlife

As far back as the early 18th century, Soho had started to become known for its cosmopolitan atmosphere and as a centre for entertainment. This began in the area around Leicester Square, but soon spread to other parts of Soho, leading to music halls, theatres, restaurants and numerous drinking establishments being opened.

As immigrants from various countries began opening restaurants in Soho, so more people were attracted to the area to eat. Sadly, many of the famous and colourful eating places have closed, but the area is still known for its great variety of places to dine. The same applies to its pubs and clubs. Whilst many have closed, there are still a number of pubs – some colourful, some seedy, some just eclectic – that date back to the 18th or 19th centuries and which have fascinating histories. Some have been patronised over the years by some of London’s more famous and eccentric citizens. We see several of these (both famous pubs and I’m sure a few eccentric citizens) on the walk.

Soho and sex

As Soho became better known for its popular entertainment, some areas started to become, shall we say, more risqué. This led to the area also becoming known for sex, particularly prostitution. There were a number of areas known for this – Covent Garden was another – but unlike the others, Soho’s relaxed attitude to such things led to it becoming known as London’s red-light district and a centre for ‘all things sex’. Not only were there prostitutes ‘on every corner’, but there were a multitude of brothels and various other places of ill-repute.

This had grown after the end of the Second World War and became such a problem that in 1959 the Street Offences Act was passed, which made it illegal to ‘loiter or solicit for purposes of prostitution’. However, all this did was to ‘push the problem underground’ and instead of being on street corners, the girls rented rooms by the hour, worked in what were loosely called ‘massage parlours’ or in the many clubs that quickly sprung up. ‘Clip joints’ advertising ‘topless shows’ were everywhere and with the criminal element soon becoming involved (including the Kray brothers along with many other gangs), customers were invariably ‘ripped off’. Equally the girls were exploited and ripped off by their ‘minders’. It became so bad that it was difficult to walk along some streets, particularly at night, without being accosted by the lines of ‘touts’ who’d stand outside the clubs trying to lure customers in.

By the 1970s the local authorities could no longer ‘look the other way’, so they and the police stepped in, and clamped down hard, with regular raids on the many sex venues.

Today, the sex business is now confined to clubs in just one or two back streets and even those are now far more strictly controlled than ever before. However, Soho has continued to be one of London’s premier nightlife areas.

Soho and the LGBTQ+ community

Soho’s diverse, artistic and cosmopolitan population has meant Soho has long been popular with the gay community. Oscar Wilde was certainly a regular visitor to bars and restaurants here, particularly Kettner’s, which we pass on the walk.

It was after the local authorities had clamped down on the illegal sex activities in the 80s that Soho rapidly became more popular with the gay community, helped of course by the decriminalising of homosexual activity and the fast-changing public attitudes. Soho became the centre of what is called ‘the pink pound’, and now many famous gay bars can be found here, particularly in and around Old Compton Street, which has been at the heart of London’s LGBTQ scene for decades.

THE STORY OF CARNABY STREET AND MEN’S FASHION

Part 1

The story of how Carnaby Street became inextricably linked with men’s fashion (and later women’s as well) began with a shop called ‘Vince’, and later one of his employees, John Stephen.

Vince was the brainchild of Bill Green, a photographer who specialised in homo-erotic portraits of the male physique. He worked under the name of Vince, at a time when homosexuality was still illegal. Green developed tiny pairs of bikini-style briefs for his models to wear, which he then began to sell to other gay men by mail order. They became so popular that he opened his shop in Newburgh Street. Besides selling other clothes from wholesalers, Green also continued to design them himself, which were produced by the many tailors in the surrounding streets. The clothes were described as ‘leisure wear’, with more than a hint of Italian and Continental style, far removed from the boring post-war suits that most men wore then. One of his inspirations came after a holiday in France in 1952 where he noticed the ‘existentialist’ look of clothes worn by young Parisian men – black sweaters and black jeans.

He was the first to introduce this look to British men, which he sold in his new shop. Besides the clothes inside the shop, his window displays were also regarded as quite shocking at the time, with mannequins dressed in briefs, or pink hipster trousers.

His choice of location for the shop was not accidental – in the 1950s, this part of Soho was the centre of the ‘gay world’. Marshall Street Public Baths – a popular place for gay men – was just around the corner. However, Vince’s clientele quickly expanded beyond the gay community. For the first time it was acceptable for heterosexual men to wear a style of clothing that had previously only been worn by homosexuals. It was also when leisure wear became chic – jeans and sweaters could be worn for an evening out.

His unconventional designs and unusual fabrics such as velvet and pre-faded denims, appealed to artists, actors and ‘bohemians’. People such as Peter Sellers, young model-soon-to-turn-actor Sean Connery, Pablo Picasso – even the king of Denmark – were customers. As was jazz musician George Melly (who joked: “I went into Vince’s to buy a new tie and they measured my inside leg.”)

Part 2 – John Stephen, the ‘£1 million mod’

The story now moves on to John Stephen, a young man from Glasgow, who opened the first men’s wear shop in Carnaby Street. He rapidly followed this by opening many others and became responsible for making Carnaby Street the centre of the ‘60s Swinging London. He was actually as revolutionary in men’s fashion as Mary Quant was in women’s but is now a rather forgotten name.

He had come to London at the age of 18 and, being interested in fashion, accepted a job at Moss Bros in Covent Garden. It was there he learned the art of tailoring and, as a salesman on the shop floor, earned a salary of £6 a week. Not being comfortable with the formal atmosphere of Moss Bros, he then realised the lack of shops selling modern clothes for the youth in London. He’d seen the huge growth in ‘Teddy Boy’ fashion and realised that it was the beginning of a new era, one where teenagers would search for their own identity which they could express through clothing.

In order to earn enough money to open his own shop, he worked double shifts and as well as his ‘day job’ at Moss Bros, he worked as a waiter in the evenings. Then in 1956 he started working for Bill Green in his shop ‘Vince’ – the ‘cutting edge boutique’ in Newburgh Street that I mentioned above.

Bill Green hired him as he felt that Stephen’s enthusiasm, good looks and style would make him popular with customers. However, Stephen saw the job as merely the first stage on the ladder to running his own business, and just a year later, in 1957, opened his own shop at 19 Beak Street.

Initially John simply copied many of Bill Green’s designs – hipster trousers, multi-coloured denim and rather exotic colours, certainly for men. Before his shop had begun making a profit, he opened a second – this time at 5 Carnaby Street. In 1959, he opened a third in Carnaby Street and by 1966 he owned fourteen in the street, besides branches elsewhere.

Part of his success was his ability to anticipate the latest fashions before they even happened! He’d spotted the rise in the ‘mod’ culture and was constantly bringing in new styles, almost on a weekly basis. He introduced collar-less suit jackets before the Beatles were pictured wearing them and sold paisley ties and polka-dot shirts before they became fashionable. He also made sure that his clothes could be afforded by the average young working man, which played a huge part in his success.

Another part of the success was that his customers began to include the leading pop stars of the day. By 1960, Cliff Richard and Billy Fury were already wearing his clothes and they were soon followed by top bands such as The Who, the Kinks and the Rolling Stones.

Towards the end of the 60s, Stephen’s designs moved on with the fashion once again – in 1967 he started incorporating Indian aspects and colourful kaftans and tunics in his clothes, rapidly becoming part of the hippie fashion. Then the ‘Regency’ foppish dandy outfits inspired by Regency fashions.

Thus began the unbelievable and unstoppable success of Carnaby Street, which continues to this day. It was all the more astonishing if you bear in mind that at the time the street was simply a Soho back street, with just a few shops selling essentials such as tobacco, as well as hosting an electricity sub-station. And as a result it took just six years for Carnaby Street to become the world-wide centre of men’s fashion!

However, as with fashion itself, Stephen’s reputation as a ‘cutting edge’ designer began to fade in the late sixties. In 1975 he sold his company, which, by then was struggling with financial problems. It finally ceased to exist in 1986, Stephen disappeared from the public eye, and he died in 2004.

I have taken much of this from an excellent blog/website called A Dandy in Aspic, written 10+ years ago by ‘Peter’ about so much of life, music, fashion, etc. in the 1960s.

FRENCH HUGUENOTS

From the second half of the 16th century onwards, religious persecution in France and neighbouring countries against Protestants, who had broken away from the established Catholic church, resulted in large numbers of immigrants coming to London. Many were Calvinist Protestants, who were known as ‘Huguenots’, and were from the cities rather than peasants from the countryside. They tended to be well-educated and skilled artisans, merchants and professionals. Some settled in Kent, near to the channel ports where they would land, but most travelled to London.

They established a church in the City of London, but it was demolished in 1841 to make way for the approaches to the new Royal Exchange and the church eventually moved to Soho Square.

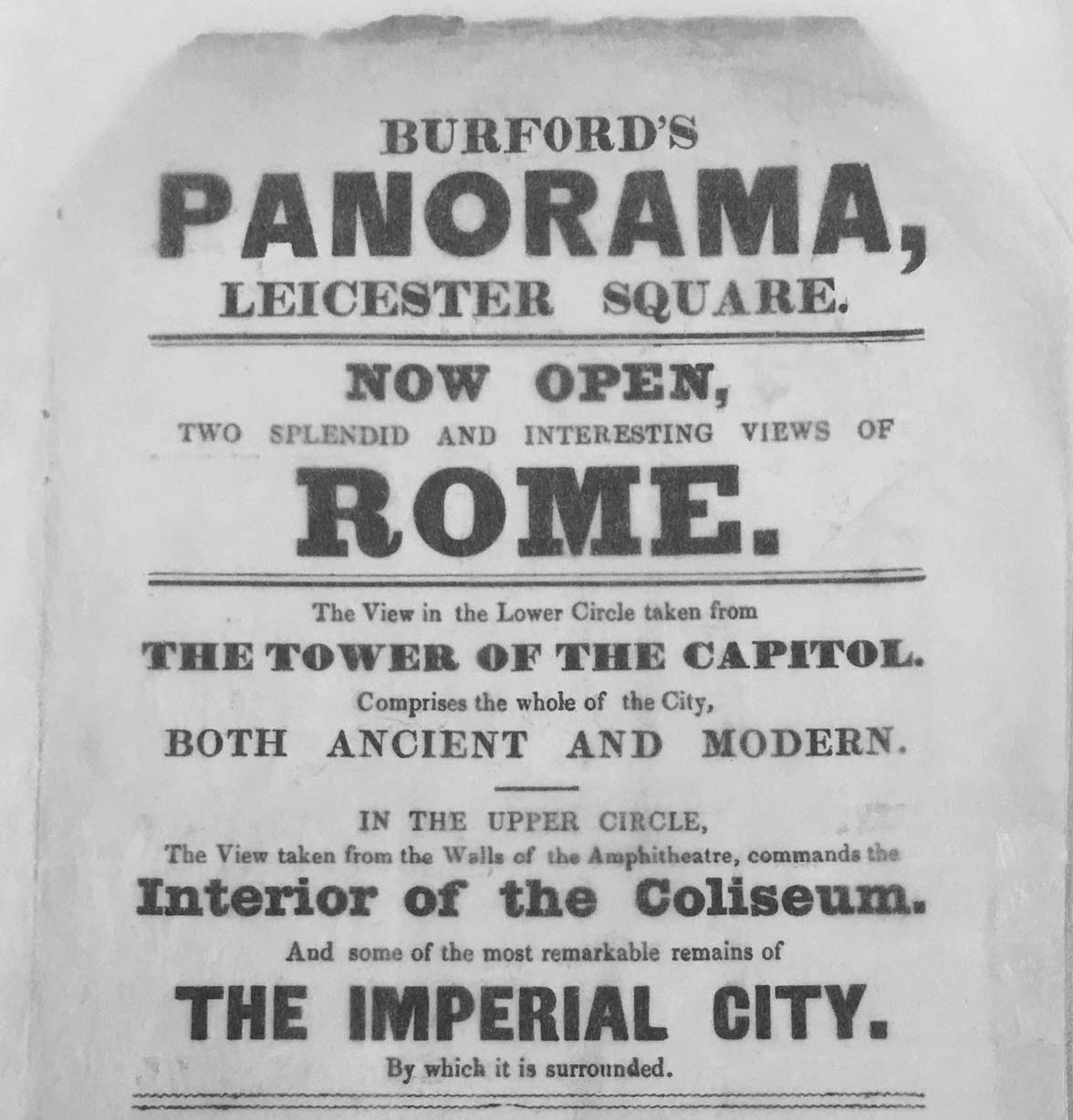

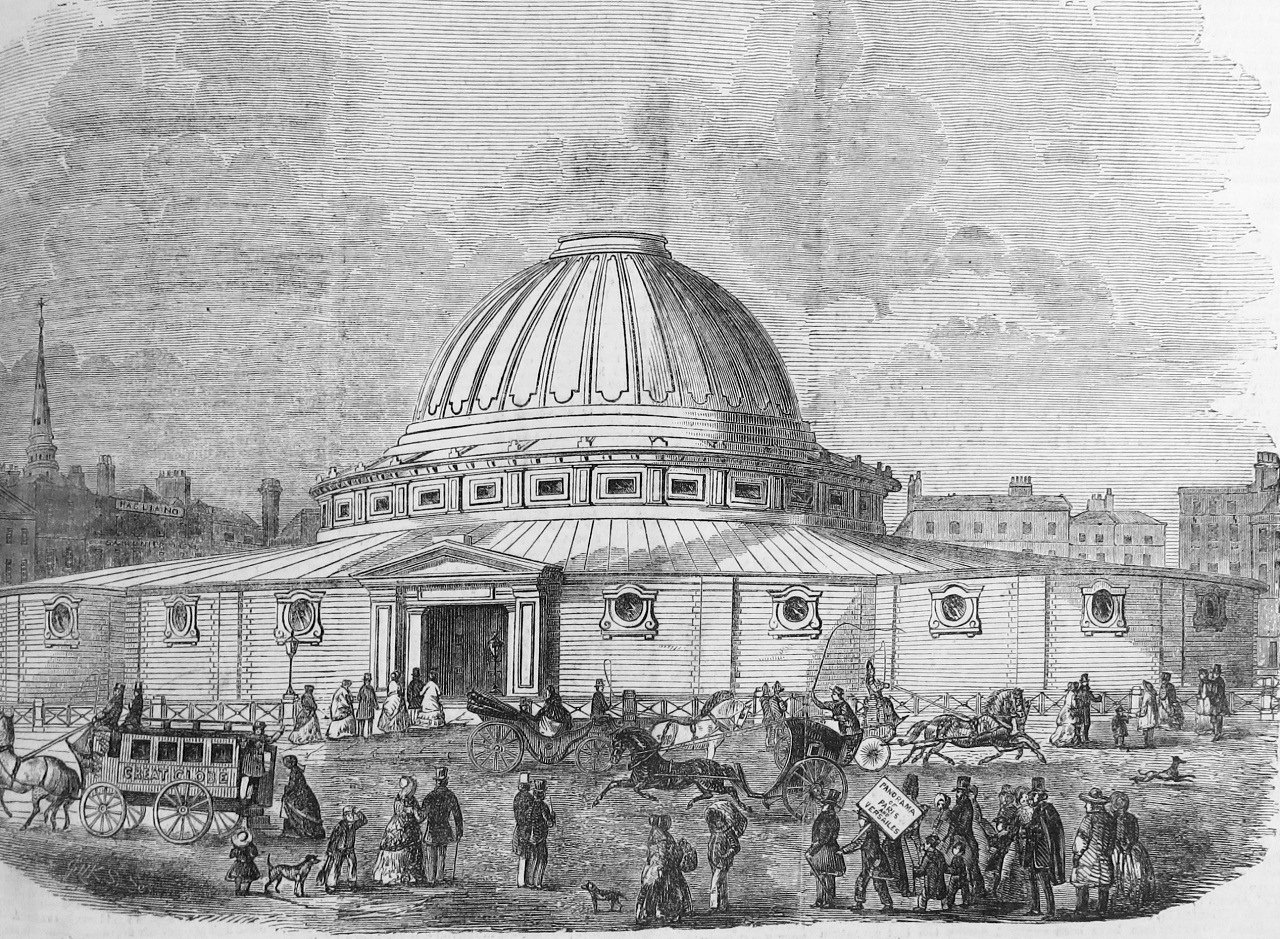

BURFORD’S PANORAMA

I have mentioned Burford’s Panorama in the walk. It opened in what later became the church of Notre Dame de France in Leicester Place in the early 1800s.

Burford’s Panorama was an enormous rotunda which displayed equally enormous 360⁰ panoramic paintings. The Panorama was an ‘early form of visual entertainment for tourists’.

They were enormous panoramic paintings that depicted scenes of cities, at first of London, but later of other cities in Europe. In those days even people living in London would have little overall idea of what their city looked like, let alone what other cities across Europe such as Venice or Paris looked like. They were a sort of Georgian-era IMAX.

Whilst over the years they displayed a number of what must have been fascinating scenes, I’ve found an interesting description of one of them – the Battle of Sebastopol, which was published in Punch magazine in 1855. I’ve copied it in its entirety here, as I think it gives an excellent idea of what people thought about these panoramas.

“To see Sebastopol it is not necessary to go abroad; it is enough to travel to the foreign quarter of London only. This journey has been performed by ourselves. We have been to see Mr. Burford’s Panorama of Sebastopol in Leicester Square and recommend all our readers who are within reach of it to do themselves the same pleasure. The London “season” being now over, there are few places either of instruction or entertainment remaining open, and this is a place of both. Moreover, as Rank and Fashion have for the most part left Town, the possibility of seeing all that is to be seen in the Panorama – to wit:, very much – is likely to be increased by some diminution of the hitherto attendant crowd of the nobility, gentry, and clergy. There will be less danger than there has been heretofore of having one’s corns crushed by a duke, of being hustled by an earl, or elbowed about and squeezed by peeresses and maids-of-honour, the bulk of a bishop being, in the meanwhile, interposed between one’s eye and the canvas. However, to secure a good view of the exhibition, it may be advisable to go early in the morning, while Rank and Fashion are at breakfast, or late in the afternoon when Rank and Fashion are at dinner.

“Sebastopol is depicted as firing and under fire, and the first impression derived from the view of the beleaguered city, presented by Mr Burford, is that of astonishment at the preternatural stillness, comparatively speaking, of the scene. Comparatively speaking, because a considerable noise is being made by Mrs Major M’Gab or some other military lady, who is sure to be present, and to be explaining the positions of the Allies with commanding gestures, in a loud voice. Astonishment, because the picture has such an air of reality, and the smoke of the bombardment looks so particularly natural, as to make you wonder at not hearing the artillery’s roar and the crack of the rifles.

“The visitor finds himself situated, with reference to the Crimea, precisely as, with allowance for change of circumstances, he would be with regard to London if he were on the top of St. Paul’s: except that the objects below him do not seem so distant, and that the smoke of the ordnance does not obscure the prospect like the smoke of the chimneys. He sees the bays and harbours that surround the Crimean coast, the Allied Fleets, the enemy’s vessels, as many as have not been sunk, and the mast-heads of those; and all the forts and batteries – the Mamelon, Malakhoff, Redan, Flagstaff, Quarantine, Constantine, Nicholas, Alexander, Star, and so forth: also the encampments of the Allies and the head-quarters of the Generals, together with a number of other objects which, recalled to his mind’s eye, will enable him to read the Times every morning with the advantage of illustrations.

“There is somebody present (besides Mrs M’Gab) who will oblige the company with any information they may desire in reference to the particulars of the Panorama.

“It is not too much to say, that those who visit Mr. Burford’s Sebastopol will see more of that City than they would if they we stationed before the Czar’s: for the Panorama was painted some little time ago, since when a great many of the buildings represented in it have been demolished: and we hope the time will very soon come when the only correct picture of Sebastopol will be the accurate likeness of certain heaps of rubbish.”

LEICESTER SQUARE & THE ALHAMBRA THEATRE

Leicester Square is well-known for being a centre of London’s entertainment, particularly its cinemas, which over the years have hosted numerous film premieres and award evenings. It also has several casinos, particularly the enormous Hippodrome, as well as many pubs and restaurants, though they are generally more popular with tourists than locals.

However, the area has been popular for entertainment since Victorian times. Back then, Leicester Square boasted numerous attractions for Londoners. Among them were Wyld’s Great Globe, the Savile House Museum, Burford’s Panorama and the Alhambra, with a Moorish façade, dome and minaret-styled towers.

The Alhambra was by far the most successful. It opened in 1854 with the official name of the Royal Panopticon of Science Arts, featuring art exhibitions and scientific demonstrations. It was built on the site of today’s Odeon Luxe cinema but despite its initial success, it closed just three years later.

It was sold to E.T. Smith, who already owned theatres and saw its potential for more general entertainment, reopening it the following year as the Alhambra Circus. It then had a circus ring and was licensed for music and dance, offering both variety and ballet performances. It was later sold to William Wilde Jnr, who continued with both the music hall and circus shows, calling it the Alhambra Music Hall. It continued to feature musicals and ballets, and with improved staging and quality of acts its popularity increased. It was said to have been the first theatre to bring the latest Parisian Can-Can style of dancing to London. However, this most risqué of dances resulted in the Alhambra soon losing its license for dancing.

At the same time its new Promenade bar had become infamous for allowing unaccompanied women, something distinctly frowned upon in those days, and its already tarnished reputation became ever sleazier. As a result it became popular with prostitutes, whilst female performers would drink, eat and flirt with male guests in between scenes. Some dancers were also said to be moonlighting in the sex trade alongside their stage careers. An American writer wrote of his shock at what he witnessed at the Alhambra, saying it was “the greatest place of infamy in all London.” He went further, suggesting the men didn’t come to watch the performances, but “the chief attraction is the women.”

I rather like the following, which I have taken from Michael Sadleir’s 1940 book ‘Fanny by Gaslight’ …

“You must please imagine yourself a man about town, with money in your pocket and a fancy for a night of pleasure. It is early in the year 1870. You find a congenial companion with similar inclination, and after a leisurely dinner at the club you find yourself looking at the Alhambra. You are purposely too late for the strident ‘variety’ with which the programme opens, but in easy time for the Ballet which concludes the first half and is followed by a long – a very long – interval. The interval is one of the main features of the show, for the huge basement canteen is open to any of the audience who think a visit worthwhile … You wander down after the ballet, pick up a couple of dancers and buy them champagne. They are cheerful young women still wearing their scanty ballet costumes and with plenty to say for themselves. Nearly an hour passes in telling stories and gossiping about the crowd of swells and chorines who skirmish and lounge and laugh in the long, bare but well lighted room. It is now nearly time for the notorious Can-Can, and you prepare to return to your seats. The ladies wish to say thank you for their wine, and each, with an arm round your neck or his, puts unmistakable provocation into her kiss. She probably ventures other familiarities, and certainly asks softly if you will be near the stage-door when the show is over.”

The Alhambra was destroyed by fire in 1882 and subsequently rebuilt and just four years later it began the occasional screening of the very earliest films, though still with its music hall entertainment. Indeed, in 1923, actress Dame Gracie Fields starred at the Alhambra in ‘Mr Tower of London’ and then a couple of years later it hosted the Royal Variety Performance, which was broadcast by BBC radio. However, during the 1930s the increasing demand for cinema films saw the theatre being sold in 1936 and demolished, with the Odeon Luxe that we see today being built on the site.

THE CONDITION OF LEICESTER SQUARE IN THE 1870s

I have reprinted here an excerpt from Walter Thornbury’s ‘Old and New London’ (1878), as I feel it explains in excellent detail how Leicester Square looked in the latter part of the 19th century, and before the garden/park in its centre was laid out.

“On the removal of Wyld’s Great Globe [shown in the illustration], after occupying the square for about ten years, the enclosure became exposed once more in all its hideous nakedness. From that time down to the middle of the year 1874, its condition was simply a disgrace to the metropolis.

“Overgrown with rank and fetid vegetation, it was a public nuisance, both in an æsthetic and in a sanitary point of view; covered with the débris of tin pots and kettles, cast-off shoes, old clothes, and dead cats and dogs, it was an eye-sore to every one forced to pass by it. As for the “golden horse and its rider,” the effigy of George I, which had been set up in the centre of the enclosure when Leicester House was the “pouting place of princes,” besides having suffered all the inclemency’s of the weather for years, it had become the subject of every species of practical joke by almost every gamin in London. The horse is said to have been modelled after that of Le Sœur at Charing Cross; whilst the statue of George I. was considered a great work of art in its day, and was one of the sights of London, until after a quarter of a century of humiliations, after being the standing butt of ribald caricaturists, and the easy mark of witlings, it gradually fell to pieces.

“The effigy of his Majesty was the first to be assailed. His arms were first cut off; then his legs followed suit, and afterwards his head; when the iconoclasts, who had doomed him to destruction, at last dismounted him, propping up the mutilated torso against the remains of the once caracolling charger on which the statue had been mounted, and which was in nearly quite as dilapidated a plight. It would be almost impossible to tell all the pranks that were played upon this ill-starred monument, and how Punch and his comic contemporaries made fun of it, whilst the more serious organs waxed indignant as they dilated on the unmerited insults to which it was subjected. One night a party of jovial spirits actually whitewashed it all over and daubed it ignominiously with large black spots.

“The disgraceful state of Leicester Square became such that it attracted the attention of Parliament, and innumerable were the discussions that took place upon it, with, however, little amelioration in its actual condition. In the year 1869 it was reported that the enterprising proprietors were about to sell the land for building purposes, but upon a communication being sent to the Board of Works, informing them of the fact, it was resolved that the Board would “do all in its power” to prevent the open space from being swallowed up by bricks and mortar. The owners of the fee-simple in the land had all along, in a sort of dog-in-the manger spirit, not only refused to reclaim the square themselves, but had resisted every effort, or refused every offer of other more beneficent persons, who were willing and eager to undertake a work which it should have been their first duty to accomplish. At length, after an immense amount of litigation, it was finally settled by a decision of the Master of the Rolls, in December, 1873, “that the vacant space in Leicester Square is not to be built over, but will be retained as open ground, for the purposes of ornament and recreation.”

“A ‘defence committee’ was established and owing to their initiative Mr. Albert Grant was led to make an offer of purchasing the square. Early in 1874 that gentleman set measures on foot which finally resulted in his obtaining possession of the square, on the payment of a large sum for purchase-money to the proprietors. He had determined to present it, as a people’s garden, to the citizens of the metropolis; and the purchase having been effected, steps were immediately taken to carry out the intentions of the donor.

“In laying out the ground, nothing pretentious was attempted. The central space was converted into an ornamental garden, and adorned with statuary, &c. The principal ornament of the new square is a white marble fountain, surmounted by a statue of Shakespeare, also in white marble, the figure being an exact reproduction by Signor Fontana of the statue designed by Kent, and executed by Shumacher, on the Westminster Abbey cenotaph. The water spouts from jets round the pedestal, and from the beaks of dolphins at each of its corners, into a marble basin. Flower-beds surround this central mass, and the enclosure—so long a squalid and unsightly waste—is now a gay and pleasant garden of flowering shrubs, green plots, inlaid with bright flower-beds and broad gravelled paths. In each angle of the garden is a bust of white marble on a granite pedestal. To the southeast stands Hogarth, by Durham; to the southwest, Newton, by Weekes; to the north-east, John Hunter, by Woolner; and to the north-west, Reynolds, by Marshall.

“The ceremony of transferring the ground to the Metropolitan Board of Works for the enjoyment of the public, took place on the 9th of July 1874. The sum expended by Mr. Albert Grant in purchasing the property and laying out the grounds, &c., amounted to about £30,000.”

GREEK STREET

Greek Street was created around 1680. A number of Greek immigrants arrived in London in the 17th century when the revived power of the Ottoman Turks caused many Greek Christians to seek refuge in London as well as other cities in Europe.

By 1691 the street was almost fully developed. Back then the street was more prestigious than it was later, with records showing there were four knights living there, while in 1714 there were two earls, a lady and a baronet. As elsewhere in Soho, it probably became less attractive to the ‘titled’, as the influx of Huguenot immigrants meant nearly a quarter of the residents were French by the early part of the 18th century.

I have reprinted here another excerpt from Walter Thornbury’s ‘Old and New London’, as it gives a little background to the area around Greek Street, Crown Street (formerly Hog Lane and since replaced by Charing Cross Road) and Rose Street (now Manette Street):

“The narrow, winding lane running southwards from the corner of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road, now known as Crown Street, but in former times as Hog Lane, forms the boundary between the parishes of St Giles and St Anne, Soho. Its narrowness and its windings alike serve to show its antiquity; and, no doubt, it derived its first name from the pigs that fed along its sides when it had green hedges and deep ditches on either side. In 1762 it came to be dignified by its more recent appellation from the ‘Rose and Crown’ tavern. Rose Street runs out of Crown Street, on the west connecting it with Greek Street. In it was a Greek church, built for the use of “merchants from the Levant,” dating from the time of Charles II. This edifice helped to give its name to Greek Street adjoining. It does not appear, however, to have remained long in the hands of these oriental Christians, but to have been given up to the use of the French Protestants who settled in this neighbourhood in large force. As such it is immortalised by Hogarth. The Greek inscription still remaining over the door, however, points plainly to its original destination.”

Today there is little evidence of Greeks having lived here, and whilst there are a number of restaurants in Greek Street, to my knowledge none are Greek. One that was here for many years and now sadly disappeared was Jimmy’s, described as a bargain-priced basement Greek restaurant. I’ve read it described as “musty and dark, with terrible wine, but with food that was a thing of wonder; cheap and plentiful enough to feed a Trojan army.” It was a favourite haunt at the time of a young Russ Willey, who went on to write two books on London, as well as creating the Hidden London website. He is also the designer of this website, an enthusiastic supporter of my project, and in the process has become a good friend!

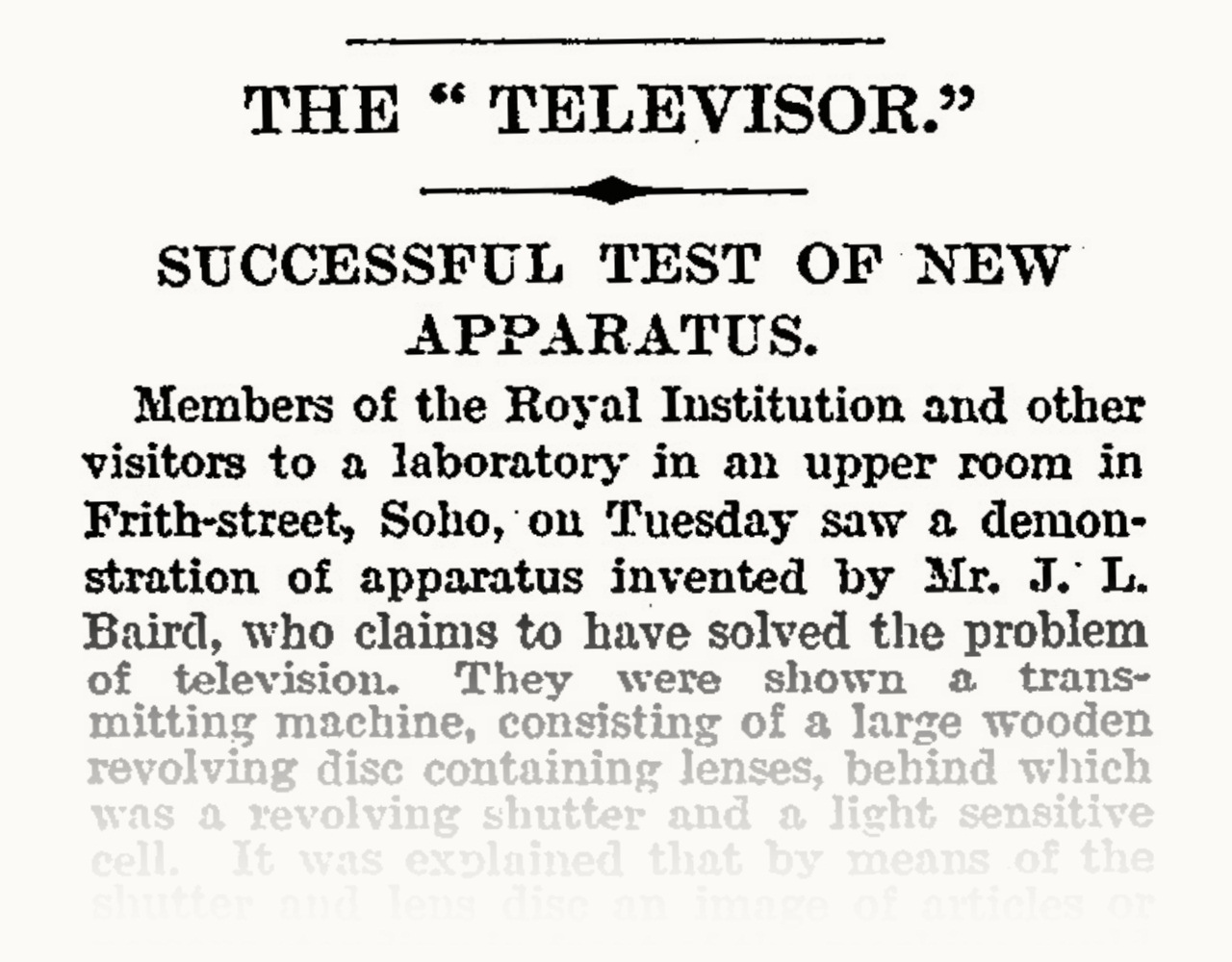

JOHN LOGIE BAIRD

The building has a special history because in 1929 it was where John Logie Baird gave his first demonstration of the wonders of his new invention – television. He also conducted early experiments with stereoscopic (3D) and colour television.

Baird, who had previously been living in Hastings, moved to Frith Street following a minor accident in which one of his experiments went wrong and his landlord asked him to move.

He was building what was to become the world’s first working television set, using items that included a tea chest, old hatbox, bicycle light lenses, scissors, darning needles – all held together with sealing wax and glue. Baird went downstairs and fetched a young office worker as he wanted to see what a human face would look like, and he became the first person to ‘appear on television’.

I’ve read somewhere that the proceedings were interrupted by prostitutes banging on his door – they’d seen the odd contraption in the window and had convinced themselves that he was spying on them.

And whilst it is possibly irrelevant, I do like the story of how when he was looking for publicity for his new invention, he visited the Daily Express offices in Fleet Street. The editor was said to have been terrified by him and was quoted as saying to a member of staff: “For God’s sake, go down to reception and get rid of the lunatic who’s down there. He says he’s got a machine for seeing by wireless! Watch him — he may have a razor on him.”

THE TELEVISOR

Extracts from The Times, 28th January 1926

“Members of the Royal Institution and other visitors to a laboratory in an upper room in Frith Street on Tuesday saw a demonstration of apparatus invented by Mr JL Baird, who claims to have solved the problem of television.

“They were shown a transmitting machine, consisting of a large wooden revolving disc containing lenses, behind which was a revolving shutter and a light sensitive cell. It was explained that by means of the shutter and lens disc, an image of articles or persons standing in front of the machine could be made to pass over the light sensitive cell at a high speed.

“The current in the cell varies in proportion to the light falling on it, and this varying current is transmitted to a receiver where it controls a light behind an optical arrangement, similar to that at the sending end. By this means a point of light is caused to traverse a ground glass screen. The light is dim at the shadows and bright at the high lights and crosses the screen so rapidly that the whole image appears simultaneously to the eye.

“For the purposes of the demonstration the head of a ventriloquist’s doll [apparently named ‘Stooky Bill’] was manipulated as the image to be transmitted, though the human face was also reproduced.

“The visitors were shown recognizable reception of the movements of the dummy head and of a person speaking.

“It has yet to be seen to what further developments will carry Mr Baird’s system towards practical use. He has overcome apparently earlier failures ….

“Application has been made to the Postmaster-General for an experimental broadcasting licence, and trials may shortly be made from a building in St Martin’s Lane.”

NUMBER 20 FRITH STREET

From various sources I found a surprising amount of information about No. 20. Some of the dates slightly overlap, and it is a little confusing, particularly in later years, as the premises seemed to be in ‘multiple-occupation’.

However, back in the 1820s the house was occupied by a bookseller, followed then by a house decorator, plumber and glazier. Then in the early 1880s the house was used by the miniaturist Jean-Baptiste Troye to exhibit his dioramas, which were scale models of landscapes. They were said to be “the most beautiful models and reliefs of countries, cities, mountains, etc., celebrated either for natural beauty or historical occurrences associated with them.”

The Soho Club for Working Girls met in a workshop at the rear of 20 Frith Street between 1880 and 1884. The club was established by the Honourable Maude Stanley to improve the lives of young women workers in London and provincial towns. However, the premises proved to be too small, and in 1884 Miss Stanley purchased, with the aid of many benevolent friends, a ‘commodious and beautiful building’ at No. 59 in the adjacent Greek Street. The club eventually developed into the Federation of London Youth Clubs.

From the late 1890s until 1911, Wells & Co, wholesale tea dealers, had their offices here, and it may have also been occupied during part of this period by Osborne, Garratt & Co who sold razors and hair curling tongs.

From 1911 the ground floor of the building housed the National Bioscope Electric Theatre. Remarkably, it appears from London County Council records, it had seats for 100 people, with a further 50 standing. The projection box was positioned in the yard at the rear, with films being projected onto the back of the screen. It appeared to be extremely popular, particularly with children, and a council inspector making a visit in 1913 found that children made up the majority of the audience and the numbers of them were double the number of patrons that their licence allowed.

According to the 1911 census, also based at No. 20 was an employment agency, one of a number in the area which helped foreign-born workers to find employment, particularly in the restaurant and hotel industry. The census also showed that on the upper floors were three Polish families, who were working as tailors.

Seemingly around the same time the premises were the offices of the Menchen Film Company, who also had offices and studios in France. In addition, equipment for other cinemas was offered for sale on the premises. Brandon Menchen was an American inventor and theatrical lighting designer who also had an electrical equipment business. He had come to London in 1911 and became involved in filmmaking in Austria and France. He had been planning on remaining in France, but as the German Army neared Paris in the First World War, he escaped back to London, bringing with him many cans of films.

By 1915 there were two businesses registered as being at No. 20; the Cinema Auction Mart and Exchange, who were ‘agents for theatre property’ and the American Export Company. The latter was opened by a friend of Menchen’s and imported trucks from the USA. Menchen himself designed an experimental flame thrower for the British Army, and the address for the patent for a later model is shown as being 20 Frith Street.

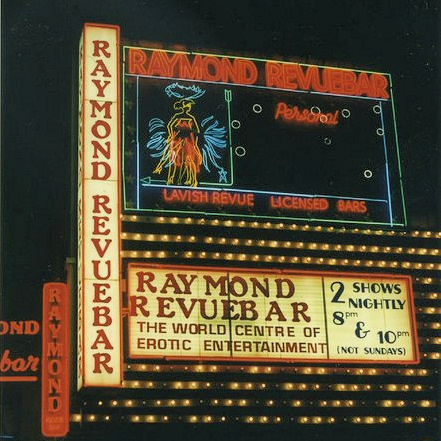

PAUL RAYMOND

Paul Raymond was a controversial character, and one of his early ventures was to open the Raymond Revuebar (shown in the photo in 1997). In 1978 he bought the Windmill Theatre, which we saw earlier in the walk. He went on to buy more theatres and open more ‘sex-themed’ shows, including the Whitehall Theatre where he opened the ‘sex comedy’ Pyjama Tops which ran for several years with a number of sequels. He also diversified into ‘men’s magazines’, such as Mayfair and Men Only.

As a result of his investment in property he later became one of Britain’s wealthiest men. When the police clamped down on the many illegal ‘sex clubs’ in Soho and the value of their properties fell, he swooped in, and at one time was said to be buying a new freehold every week. In 1992 he was said to be the richest man in Britain and worth £1½ billion. He eventually owned an estimated four hundred properties in Soho alone.

After his death in 2008, his fortune was left to two of his grandchildren – India Rose James and Fawn Ilona James.

For more information about Paul Raymond, see Wikipedia; for his obituary, see the Guardian – and for some gossip, see the Daily Mail.

THE POET, THE PILLARS AND THE RIPPER

I like the story about Francis Thompson, the poet and Catholic mystic, who, having given up medical school to concentrate on his writing, lived rough in Soho. He became addicted to opium, but continued to write, eventually sending a parcel of his scruffily written poems to the editor of a Catholic literary magazine. I have put a copy of his letter in the next section, but I’ll just say here that the only address Francis gave for himself was ‘care of the Charing Cross Post Office’. However, the editor was so impressed with the poems that he undertook a search of Soho to find him – which he did, lying ‘stoned’ on opium in the entrance to the Pillars of Hercules. I’ve also included a reference to the possibility of him being Jack the Ripper.

Dear Sir,

In enclosing the accompanying article for your inspection, I must ask pardon for the soiled state of the manuscript. It is due, not to slovenliness, but to the strange places and circumstances under which it has been written … I enclose a stamped envelope for a reply … regarding your judgement of its worthlessness as quite final.

Apologising very sincerely for my intrusion on your valuable time,

I remain, Francis Thompson

I have taken the following from one of the many Jack the Ripper websites:

Richard Patterson has spent 20 years investigating Jack the Ripper. Richard, an Australian teacher, has come to the conclusion Francis Thompson is Jack the Ripper.

Thompson’s work wasn’t published until five years after the 1888 murders took place. Patterson is convinced the poet took to murder after a relationship with a prostitute ended. Thompson had surgery experience and was said to keep a dissecting knife in his possession. Thompson was also believed to have been taught a rare surgical procedure that appears to mimic the mutilations found in more than one victim. Patterson said, “Soon before and soon after the murders, he wrote about killing female prostitutes with knives.”

After college, Thompson moved to London and is alleged to have become addicted to opium. His first book, ‘Poems’, was published in 1893.

Thompson is said to have resided in Spitalfields at the time of the Whitechapel murders. Thompson lived at No. 50 Crispin Street, in the Providence Row night refuge. It has been claimed victim Mary Jane Kelly and Thompson stayed at the same address.

Patterson’s research has been published in his book, ‘Francis Thompson – A Ripper Suspect’. It should be noted that few Ripperologists have given Patterson’s verdict much credence.