Updated: 16 December 2019 |

|

Walk page: Click to view |

Appendix to the Sunday markets walk

MORE ABOUT THE EAST END MARKETS AND THEIR NEIGHBOURHOOD

In-depth profiles of some of the most significant places and people mentioned in the East End Sunday markets walk, together with pictures – and Charles Booth’s ‘Poverty Map of London’.

THE ORIGINAL COLUMBIA MARKET

The first Columbia Market opened in 1869 in an enormous and spectacular Gothic-style building, just a few hundred yards from where the existing street market is held today.

It was the idea of Angela Burdett-Coutts, a remarkable woman who was the granddaughter of Thomas Coutts, the founder of the famous Coutts Bank. When he died, she inherited his considerable fortune which she then used to help those less fortunate, eventually becoming known as the ‘Queen of the Poor’. (I have put a little more about this amazing woman in a separate section.)

She felt strongly about the terrible living conditions of the poor who lived in the slums of London’s Bethnal Green and, besides helping to provide land for social housing (we saw an example with the Leopold Buildings at the beginning of the walk), she was convinced they were being exploited by local traders who she believed were selling them poor quality and overpriced food. In an attempt to do something about this she paid for an enormous market building to be built.

Besides the covered market with four hundred stalls, there were also shops, flats for both the traders and other local people to live in, a church, swimming pool and baths and even a laundry. All quite remarkable for the East End at that time.

She planned for the market to be something that would rival Billingsgate which was situated just a couple of miles away in the City of London and at the time, the world’s biggest fish market. To achieve this, she and her husband, who owned a large North Sea fishing fleet, planned to build a railway line that would deliver fresh fish on a daily basis directly to their new market.

However, she hadn’t anticipated the obstacles. Firstly, and perhaps rather bizarrely, it seemed that local people still preferred to buy from the street traders or continue to go to the Billingsgate, Spitalfields or Covent Garden Markets. And of course those markets weren’t going to give up their monopolies that easily, anyway. Perhaps even more surprising, the market traders who she was trying to help, didn’t like the new buildings and preferred to continue selling their products outside in the open air as they had before. As a result the market closed just fifteen years later, and Angela handed the buildings over to the City of London for use as workshops and a workhouse.

Sadly, nothing now remains of this immensely grand building, as it was demolished in the late 1950s and new and rather nondescript houses and blocks of flats were built on the site.

ANGELA BURDETT-COUTTS

Angela Burdett-Coutts was the granddaughter of Thomas Coutts, the founder of Coutts Bank, and she had inherited his considerable fortune. With it she then dedicated much of her life to helping those less fortunate.

The list of what she achieved was simply staggering. Besides all her philanthropic work in London’s East End – for which she earned the ‘title’ of ‘Queen of the Poor’ – she funded the Church of England bishoprics in Cape Town, Adelaide and British Columbia. And it was for the latter that the road was named ‘Columbia Road’.

She helped to start, or provided early funding for, many charities, including the RSPCA and NSPCC. Amongst her many other philanthropic deeds, too numerous to mention here, were the funding of major projects to help the poor of Palestine and the Holy Land – she even led an expedition to find clean drinking water in Jerusalem.

She worked with other amazing women such as Florence Nightingale and was a friend of Charles Dickens, with whom she founded a home for ‘women who had turned to a life of immorality’.

Edward VII said of her, “After my mother, she’s the most remarkable woman in the kingdom.”

If you’d like to know more about her, I suggest you also take a look at the following Wikipedia page –

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angela_Burdett-Coutts,_1st_Baroness_Burdett-Coutts

COLUMBIA MARKET AND THE WORLD WAR II BOMBING RAID

I found a fascinating article on the BBC’s ‘WW2 People’s War’ website. Written by Tom Betts on 7th September 2005, exactly sixty-five years on from Saturday September 7th, 1940, the start of the German Blitz on London, it tells the remarkable tale of someone who was in the Columbia Market air raid shelter when it suffered a direct hit from a 50kg bomb. It is also gives some details of what life was like for a child in London’s East End during the Second World War.

Tom’s article begins:

“It was the day when my life was changed forever, although it was so very long ago, to me it is remembered as clearly as if it happened only last week.

“I can remember it not just because of what happened, but at the age of twelve and a half, as I was, I can clearly recall the comments, actions, faces of all those with me at the time. A day recorded in my memory that I will never forget.

“The Saturday was a very warm, cloudless day and just like any other early September day. We lived in Columbia Buildings, Bethnal Green. The ‘Buildings’ as they were known were a grand project built by Madam Burdett-Coutts, of the banking world, as a Victorian philanthropic venture in the 1860s It was an enormous Gothic creation comprised of a covered market, accommodation for several hundred shops and storage for the traders. It had its own church, swimming pool and baths and the luxury of a laundry on the fifth floor. By no means the typical East End block of flats, far more majestic.

“On the day in question after my mother had cooked my brother and I breakfast, friends and I went out knocking on doors to take orders for coke from the local gas works. Our ‘bit’ for the war effort paid 3 pence a sack which enabled us to buy pie and eels (Dutchy Lees) and also the means to go to the Saturday cinema. In the afternoon the sirens began but having had some few light air raids in the previous nights, we were not too alarmed. Today though was different, there was much more anti-aircraft gun activity. We were more than curious and climbed up six floors to take a better look. There were hundreds of German airplanes, so low that the crosses on their wings were clear to see. The bombs began slowly dropping from them, landing on the docks. It was bizarre, as I remember looking at the square below where children were still playing, completely oblivious to the destruction not too far away.”

To read the rest of Tom’s evocative story, visit this link:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/38/a8071238.shtml

THE OLD NICHOL

For anyone who may be interested in reading more about the Old Nichol and Boundary Estate, I have taken the following excellent account of the estate prior to its rebuilding from a book review that was published in the Daily Mail on 10 July 2008.

The book is called The Blackest Streets; The Life and Death of a Victorian Slum, which I can thoroughly recommend. It was written by Sarah Wise and published by The Bodley Head.

“Situated in Bethnal Green and part of Shoreditch, it was only 25 minutes’ walk from the Bank of England. But the Old Nichol, a maze of rotting streets hemmed in by bleak tenement buildings, might as well have been on a different planet. Most Londoners preferred to forget that it even existed.

“When Mowbray put on his boots and walked through the Old Nichol, he passed down narrow, muddy streets, skirting pools of filthy liquid and the carcasses of dogs and cats. Eyes watched him greedily through broken windowpanes. Mowbray would go on to decry the injustices of the age and was an impassioned socialist. And given his surroundings, it is hardly surprising that the slum’s most famous son spoke so loudly.

“No grass grew in this dark and putrid labyrinth. The narrow canyons of blackened brick tenements blocked out the sun and all colour was leached away except for the dull greys of smoke and soot.

“In a two-room tenement in Anne Court, just around the corner from where Mowbray lived, the meagre fire burning in the grate drew moisture out of the saturated plaster, creating wisps of fog inside the house. In the Old Nichol, there was no escape from the gloom. Its two tiny rooms were home to a married couple and six children, but there were no beds.

“When Montagu Williams, a magistrate and writer, asked how they slept, the mother replied: ‘Oh, we sleep how we can.’

“Through the hole in the wall which served as a door, Williams could see the woman’s haggard, hollow-cheeked husband and two teenage sons making uppers for boots.

“Many of these houses were below pavement level and so flooded when it rained. In cold weather – and warmth was a luxury in the Old Nichol – broken panes were blocked up with anything that came to hand: newspapers, rags, sometimes old hats. In winter, even the water jugs iced over. Mowbray lived with his wife and four children in a little room in Boundary Street, which marked the border between Bethnal Green and Shoreditch.

“Around the corner, in a single room, a missionary had recently discovered a single woman nursing a feverish young girl. On the floor lay the body of the woman’s six-year-old son, who had died a few hours earlier. Her husband, a singer of street ballads, had refused to return home because a public hanging at Tyburn had drawn the crowds and business was good.

“When he did get back to his dead child, he stormed out again at the sight of the missionary urging his wife to pray.”

It is hard to believe that such obscenities were allowed to persist in the richest city in the Empire. But, as this book reveals, they were commonplace in this corner of London. Sarah Wise’s The Blackest Streets reveals that the Nichol’s 30 or so streets housed around 5,700 people and had a death rate that was almost double that of neighbouring areas.

MORE ON THE OLD NICHOL AND THE BOUNDARY ESTATE

In 1850 Henry Mayhew, a journalist, reformer and cofounder of the satirical magazine Punch, wrote an article for the Morning Chronicle newspaper that detailed how appalling the conditions in ‘Old Nichol’ actually were. It said, “Roads were unmade, often mere alleys, houses small and without foundations, subdivided and often around unpaved courts. An almost total lack of drainage and sewerage was made worse by the ponds formed by the excavation of brickearth. Pigs and cows in back yards, noxious trades like boiling tripe, melting tallow, or preparing cat’s meat, and slaughterhouses, dust heaps, and ‘lakes of putrefying night soil’ added to the filth.”

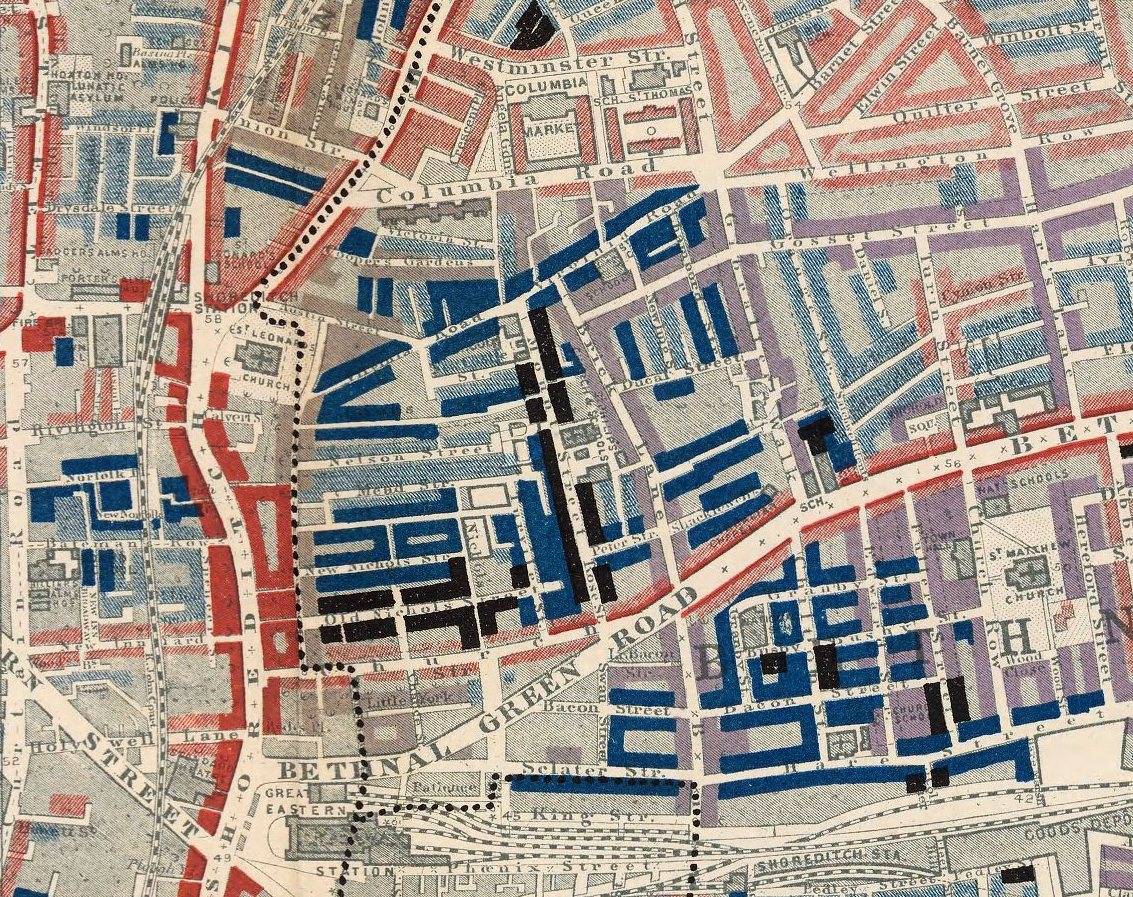

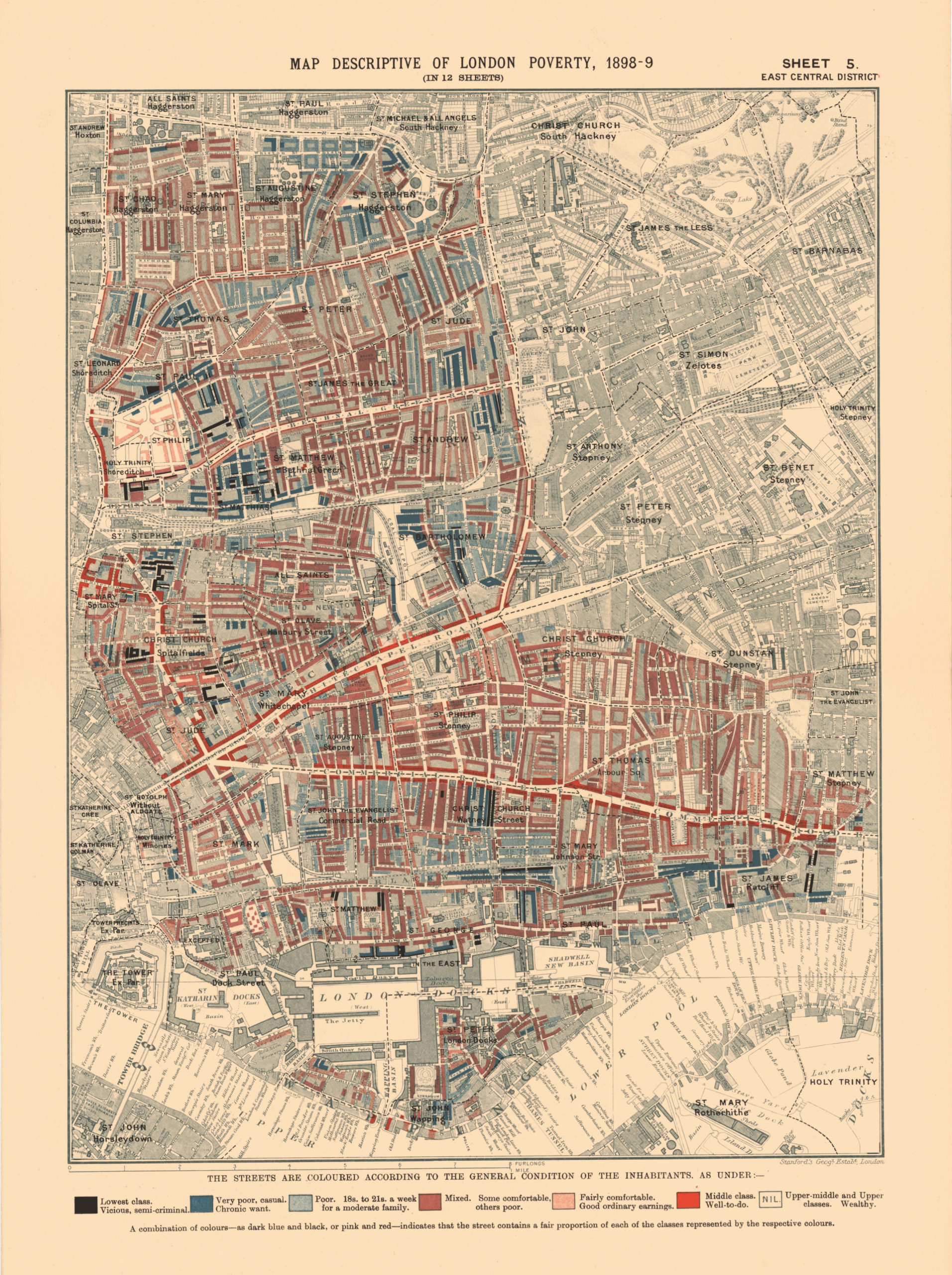

Around the same time, Charles Booth and a team of researchers had begun to visit every street in London in order to produce a map showing the levels of poverty and deprivation and its level of detail of was truly amazing. In his report on Arnold Circus Booth said that a quarter of all children living in the Old Nichol slums died before their first birthday.

On reading this report, the Reverend Jay, Vicar of the local Holy Trinity Church, took it up himself to spend more time visiting the area and helped raise money to build a church and a social club. He also encouraged Arthur Morrison, a journalist and author who wrote about life in the London’s East End as well as popular detective stories, to pay a visit to the area. This resulted in a book about the life of a child living in the slum called A Child of the Jago. Another newspaper report of 1863 said, “The limits of a single article would be insufficient to give any detailed description of even a day’s visit. There is nothing picturesque about such misery. It is but one painful and monotonous round of vice, filth and poverty, huddled in dark cellars, ruined garrets, bare and blackened rooms, reeking with disease and death, and without means, even if there were the inclination for the most ordinary observations of decency and cleanliness.”

All of this eventually prompted the council to take action, and in 1884 they engaged Owen Fleming, a 23-year old architect, to draw up plans for a new ‘council housing estate’, which was called the Boundary Project. He came up with a plan to demolish around fifteen acres of slums and build in their place a rather aesthetic concept of several wide, tree-lined streets, named after places along the River Thames. These radiated off from a central circular street – the Arnold Circus we see today. Work started in 1884 on what was said to have been Britain’s, and possibly even the world’s, first ‘council estate’.

Although the red brick houses and flats were well built, they were still basic by today’s standards. There was no individual running water and just a shared toilet and bath on the landing of each floor. (Refurbishments have since put those things right, though!)

The highpoint was, and still is, the raised garden in the centre of Arnold Circus, built using the rubble from the demolished houses, and with a bandstand in its middle.

However, despite this seemingly good progress, there was controversy at the time. Although the new development could accommodate around the same number as had been living in the Old Nichol, the process of who should and shouldn’t be offered a flat was sometimes rather arbitrary. Firstly, the rent was set at a level that few of the very poor could afford, and those who were thought to be of ‘too low a class’ were apparently sometimes refused. This meant they were then forced to move from here into other, equally crowded, slums in east London. Indeed, apparently out of the 6,000 people who lost their homes in the slum clearance, only eleven (you read that right!) were able to move into the new flats. Instead, it was artisans, clerks and even a vicar who moved in.

The Boundary Project didn’t just provide housing; two schools were built (you can see where one used to be on Arnold Circus), there were shops and workshops for the craftsmen, such as furniture and shoemakers.

In total 20 blocks of five-storey flats were erected in the seven roads that lead off from Arnold Circus. With their design inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement, they are now Grade II listed and, since the recent popularity of areas such as this with young ‘millennials’, prices of these flats have risen quite astronomically – I’ve seen them advertised at up to almost half a million pounds – and that’s for a one bed flat!

However, around two-thirds of them are still owned by the local borough council. It’s become a bit of a ‘hot potato’ as the council have been trying to pass the responsibility for the properties that they own on to a housing association, a plan that’s been hugely opposed by the existing tenants.

And the name ‘Arnold Circus’? It was named after Sir Arthur Arnold, who at that time was the Chairman of the London County Council. It is said that it was thanks to him that the actual construction of the buildings was of a sufficiently high standard that they are still in use today, as well as encouraging the estates thoughtful layout and design.

ST LEONARD’S SHOREDITCH

The church is dedicated to St Leonard, who was born in France and became the patron saint of prisoners and the mentally ill, and it still plays a significant role today in helping the less fortunate, with particular emphasis on recovering addicts.

The first church we know about was built here by the Anglo-Saxons, which was later demolished by the Normans who built a new church on the site. The first record of a vicar being appointed was in 1185!

St Leonard’s was known for many centuries as the Actors’ Church. This was because the first theatre in England was close by in New Inn Yard, where several of Shakespeare’s plays had their first performances. It is said that Shakespeare, who lived nearby, might have worshipped in this church, though not the one we see today; the church he would have known was already five hundred years old by that time. Indeed, it is reckoned by some historians that Shakespeare set the final tomb scene in Romeo and Juliet here.

A number of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, including three of the Burbage family – James, who built the first English theatre; his son Cuthbert, who built the Globe Theatre and his other son Richard who was the first to play Macbeth, Hamlet, Richard III, Othello and Romeo, are buried in the church’s crypt.

The Norman church eventually collapsed in the early 18th century. This was because of problems with the adjacent River Walbrook overflowing and damaging the foundations. A new church was erected on the site that was designed by George Dance the Elder, a pupil of Sir Christopher Wren, who had also designed the Lord Mayor’s Mansion House in the City of London. His design was not universally popular at the time. A plain Tuscan portico is surmounted by a square clock-tower and belfry. These then support the gallery with its fluted cupola. This is raised on Corinthian columns topped by a gallery reflective of the tower one. Above them rises the elegant obelisk.

These slender columns, subtle colonnades and bright, large windows were hard for people at the time to accept. Later the Victorians made further changes, sadly blocking up the ground floor windows, whilst further damage was caused to the church during the Second World War. By 1990, the building was becoming unstable and was forced to close for two years to enable substantial restoration work to take place. However, today it is regarded as being one of the most important ecclesiastical architectural structures in England.

Further repairs, paid for by the Heritage Lottery Fund, are currently taking place (2020) to the spire, tower, roof, etc.

And I will just add that the church’s situation in the heart of London’s East End, surrounded by people of different faiths, or none at all, who over the years have generally been some of the poorest in London, has meant that a significant part of the church’s role has been to try and provide them with support. That is particularly the case today, and the church has in place a number of measures – outreach, drop in centres, an 18-bed residential hostel for recovering addicts … it’s a long list.

And three final points of interest … Firstly, the church has some wonderful acoustics and is a popular place for musical performances and has been used by the BBC Symphony Orchestra amongst many others.

Secondly, those who were fans of the television series Rev., which starred Tom Holland, might recognise St Leonard’s as ‘St Saviour in the Marshes’.

And finally, in case the name of a church in Shoreditch is ringing a bell (pun intended!) then it maybe as a result of the nursery rhyme many of us learnt in childhood … with the particular line of course being … “When I grow rich”, say the bells of Shoreditch. (Oranges and Lemons …)

THE LEATHER MERCHANTS OF BRICK LANE

I found an interesting article about Brick Lane’s leather merchants on the Spitalfields Life website and have included a brief extract here:

“Not so long ago, almost all the shops north of the railway bridge in Brick Lane sold leather jackets and bags manufactured locally, but now there are only a handful of these businesses left.

“The manufacture of leather garments is an age-old industry on this side of London, existing as part of the clothing and textile trade that was a major source of employment here for centuries. A hundred years ago, the industry was predominantly Jewish but when Asian people arrived in significant numbers in the last century they worked as machinists in a trade that they eventually took over and now, a generation later, they find themselves presiding over its slow demise …

“All but one of the leather shops I visited owned their buildings, which proved to be the key factor in their survival when others that paid the escalating rents had gone. I was fascinated to find that most were run by skilled men, experienced leatherworkers who offer the facility to have clothes and bags made to order. It was even more remarkable to learn that for a modest price you can buy a good quality jacket which has been made by hand in a workshop on Brick Lane. There may be only a few left, but my discovery was that these leather shops still have plenty going for them – if people only knew.”

For the full story and a couple of dozen photographs, visit:

https://spitalfieldslife.com/2012/10/13/the-leather-shops-of-brick-lane/

For anyone interested in knowing more about this area of London, then I can thoroughly recommend this excellent website.

IMMIGRATION AND SPITALFIELDS

The Huguenots

The first recognised wave of immigrants to move here in any great numbers were the Huguenots, who came mainly from northern France, whence they were fleeing persecution from the Catholic majorities. Many settled in an area of Spitalfields through which we pass. They were often highly skilled, particularly in the craft of silk weaving and some became quite wealthy and built elegant four or five-storey Georgian townhouses. Many of these were designed with attic rooms that had particularly large windows so as to let in as much light as possible; light was vital for those who were weaving, and they needed as much of it as possible. It was a profitable business and some of the Huguenot weavers became quite wealthy. We see several streets that still contain these houses, which are now Grade I or II listed.

However, the prosperity of the silk weaving Huguenots didn’t last, as in the latter part of the 19th century the government abolished the existing heavy duties on imported silk, making business much more difficult and many moved away to find work in other parts of London and the South east.

Irish immigration

As the Huguenots moved away, the next wave of immigrants arrived, this time from Ireland. Many were linen weavers, forced to leave because of the decline of the linen industry in Ireland, and the potato famine, which caused such a devastating loss of life as a result of starvation. Many of the large houses the Huguenots had built were then sub-divided to provide cramped, but cheap accommodation for the Irish, most of whom arrived with nothing. Some rooms in the houses began to be used as workshops, where a fortunate few found work in the linen weaving trade, taking over from their previous use for silk weaving, though it was far less profitable. However, most found work in the construction industry, which was booming at that time, with docks, railways and many other major construction projects taking place in London at that time.

As the Irish began to make better lives for themselves, they too moved on to other areas of London, many to places such as Kilburn (apparently at one time it was even known as ‘County Kilburn’!).

Jewish immigration

Around the same time as the Irish had begun to settle here, so did huge numbers of Jews. They were fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe, particularly the pogroms in Poland and Russia. The number of Jews continued to grow, so much so that at one time the area was said to have one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe.

Many worked in the textile industry and set up the small tailoring and clothes manufacturing businesses for which the area became so well-known. However, by the 1950s they began moving out of the area, settling in areas of North London such as Barnet and Finchley.

The Bengalis

As the number of Jews began to diminish in the 1950s, so their places were taken by the Bengali’s. Many were from the Sylhet region of what is now Bangladesh, and many found work in the Jewish tailoring and businesses that had remained in the area. Over time, many set up their own textile businesses, mostly small and family owned and run, many of which still thrive today, as we will see when we visit Petticoat Lane area at the end of the walk.

But they didn’t all enter the ‘rag trade’, as it used to be called, and it wasn’t long before some Bengalis began opening curry houses, for which much of Brick Lane is now famous, the area even becoming known as ‘Banglatown’.

CHARLES BOOTH’S ‘POVERTY MAP OF LONDON’

In the walk I mention the survey that was undertaken by Charles Booth, whose aim was to map the streets of London and show the various levels of poverty that existed.

The information is now held in the library of the London School of Economics (LSE). There they have an archive containing Charles Booth’s Inquiry into the Life and Labour of the People in London (1886–1903).

The archive comprises over 450 volumes of interviews, questionnaires, observations and statistical information. It documents the social and economic life of London, highlighting all of its contrasts, complexities and contradictions. It also goes “behind the scenes” of the Inquiry itself, showing how Booth and his research team developed new methodologies and techniques in what is now recognised as a key milestone in the development of social research techniques. The archive can be accessed in the library’s Reading Room.

Thanks to the LSE for this information and the map below.

You can read more about Charles Booth at –

You can read more about Charles Booth at –

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Booth_(social_reformer)